Computer Air Combat by Charles Merrow and Jack T. Avery , published by Strategic Simulations, USA

First release : November 1980 on Apple II

Tested on : Apple II Emulator

Total Hours Tested : 10

Average duration of a battle : 1-3 hours

Complexity: High (3/5)

Would recommend to a modern player : No

Would recommend to a designer : No

Final Rating: Flawed and obsolete

Note that all reviews and ratings assume you have read the After Action Report. This review was updated on 03/05/2022 with new information from Joel Billings, correction on the manual content and conversion of the rating to my new system.

If you want to simulate air combat in the late 70s, you have two routes :

- The novelty route : computer games. Game designers immediately saw the potential of computers to emulate air combat, starting with the arcade games Pursuit by Kee Games in 1975 (now lost) and Interceptor in 1976, by Tomohiro Nishikado (of Space Invaders fame). Of course, I cannot say for Pursuit but Interceptor was more faking it than making it.

By 1980, the technology, while primitive, was there. FS1 Flight Simulator (1979), featuring WWI combat, was immensely popular, with according to the developer 30 000 copies sold by June 1982. For comparison, Computer Bismarck was a success for SSI at 8 000 copies sold. Yet, those games were at the same time among the most complex to code, and not quite satisfying :

- Else, you could go for the traditional “tabletop” route, turn-by-turn and top view – not necessarily less immersive given how poor computer graphics were in that era. There were in the 60s and 70s a lot of air combat wargames : Dogfight (1962), Richthofen’s War (1972), Sopwith (1972), Air Force (1976), Air War (1977), Ace High (1980), … Those games usually shared three features :

- They were pretty complex, with many rules to manage every turn,

- While complex, they still streamlined a lot of things, in particular anything related to altitude,

- In many cases they represented WWI rather than WWII (or later conflicts), as the more limited capabilities of WWI planes are easier to simulate with rules that humans can understand.

I suspect that for many players, these were the kind of games that you owned, maybe of which you played an introduction scenario, and then shelved while hoping that, one day, you would find the partner to play with. Or maybe I’m projecting my own relationship to Great War at Sea : Jutland.

Computer Air Combat is the first to offer a third route : leveraging the computer’s calculation power to not only remove the rule management problem, but furthermore offer a complex, realistic simulation that would still be managed effortlessly by the computer. Being able to simulate WWII was the cherry-on-top. Of course, the fact that the player did not have to referee at the same time did not make the game easy to play in any way.

The developers, Charlie Merrow and Jack Avery, were employees in the defence industry from San Diego. After playing Computer Bismarck, they realized SSI could publish the air combat game they had designed and coded on the side. Computer Air Combat was their first game, but Charlie Merrow had a lot of programming experience, Billings described him in 1982 as “having 22 years of commercial programming experience on 15 different computers”. For his part, Jack T. Avery seems to have been more the aviation expert and researcher. In any case, they contacted SSI, probably in early summer 1980. It was just the right moment : Joel Billings had been contacted shortly before by Danielle Bunten for Computer Quarterback, and Billings had realized that he could not only make games but also publish them. SSI saw the potential in Computer Air Combat and unlike with Computer Conflict they went all-in. The game included :

- A manual, including historical background,

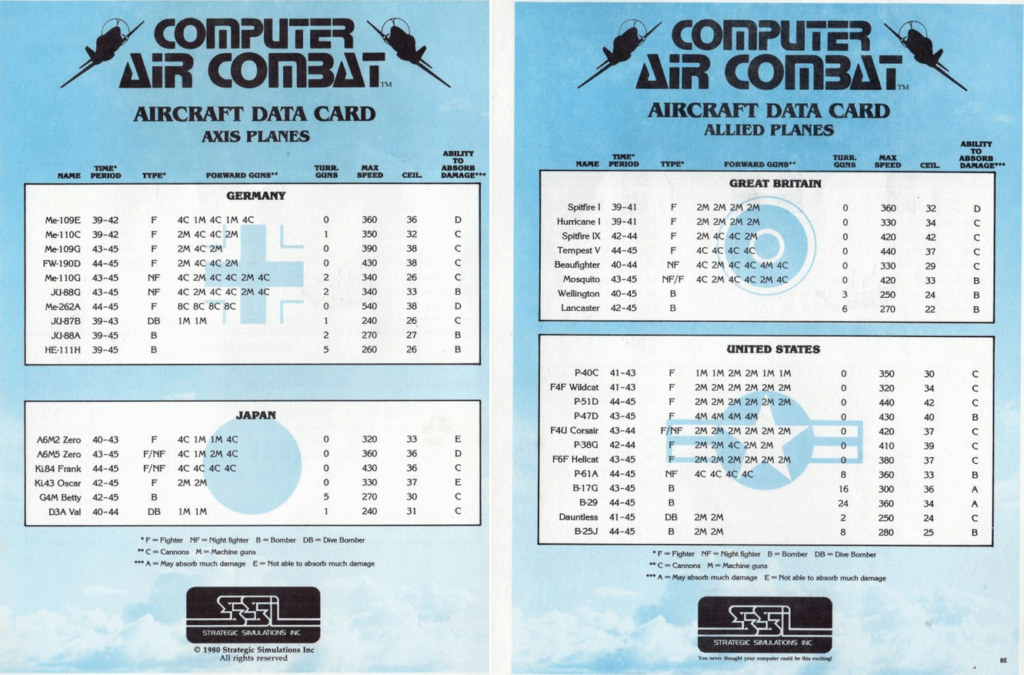

- Four reference cards : one describing the scenarios, one with the game commands, two with the stats of the planes

- A sky chart, to take note about which enemy you spotted, of course I do not believe anyone earnestly thought it was useful – but it was cool and looked serious,

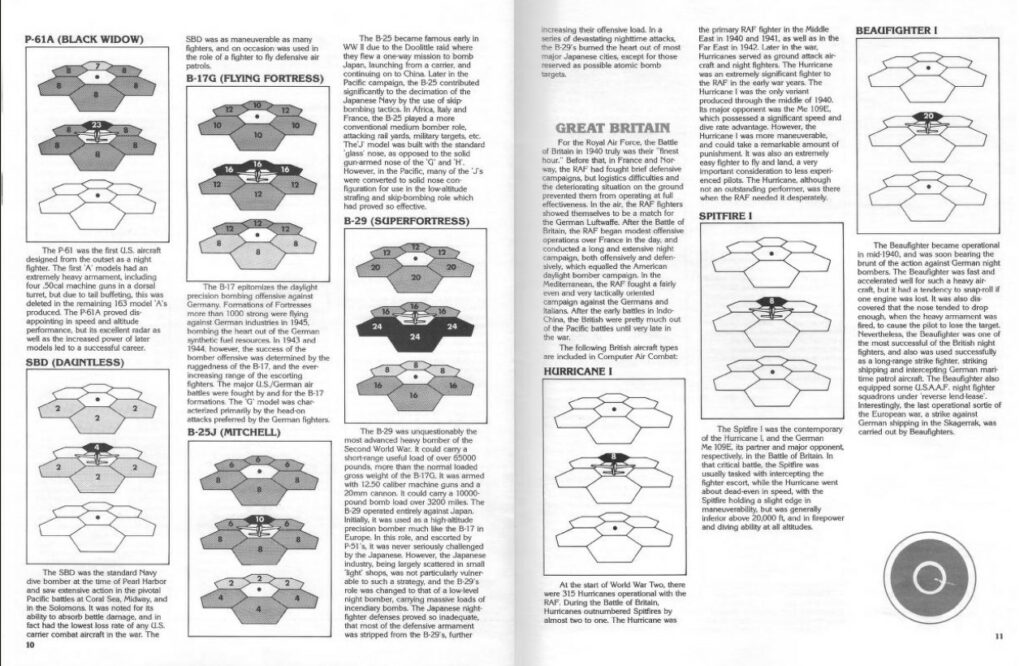

Initially, Computer Air Combat offered 36 planes from United States, United Kingdom, Germany and Japan – Soviet Union missing is a bit of a surprise.

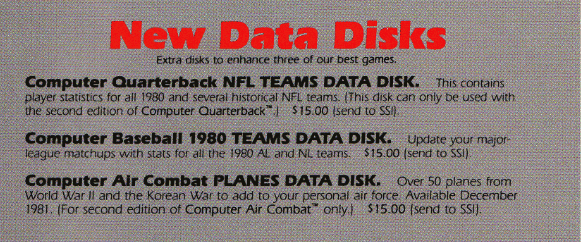

This would be corrected. I believe that Computer Air Combat, along with Computer Quarterback, would innovate in another way : they are (to my knowledge) the first computer games to offer not sequels, but expansions. I am not sure exactly when it was released, but it is there in the Winter 81-82 catalog :

As I have said in the AAR intro, the Data Disk would add German, Russian, Romanian, Polish, Italian, North Korean and “United Nations” planes , for a total of close to 60 new WW2 planes and 12 specifically Korean War planes. The update created the amusing situation that the Japanese Air Force (6 planes) has a less impressive line-up than Finland (10 planes – more than UK) or Romania (7 planes). Of course, France missing feels strange when Poland is there with 3 planes, though the 1939-1940 French planes that mattered have been allocated to Romania anyway.

That was a long intro, what did I think of the game ?

A. Systems

Starting with systems, because this is the most complex game I have reviewed so far.

The game is turn-based, with simultaneous resolution, and two phases : Movement phase and Combat phase.

- The movement phase represents 7 real-life seconds, which as we saw in the AAR allows to quickly calculate what distance in feet (the game unit for distance & altitude) will be traversed in the period (100 mph = 1000 feet in 7 seconds). During his turn, the player plots what the plane will be doing during those 7 seconds.

This distance will also be used as “action points” of sorts, in that every action will be executed after the distance has been traversed (during the 7 seconds frame, or from one turn to another).

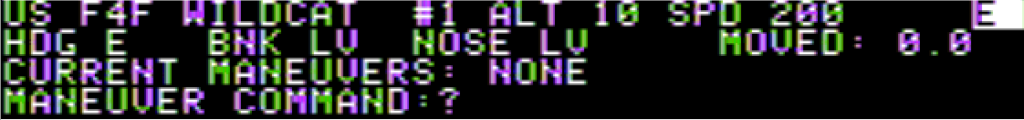

Let’s take for instance this Wildcat, going 200 mph :

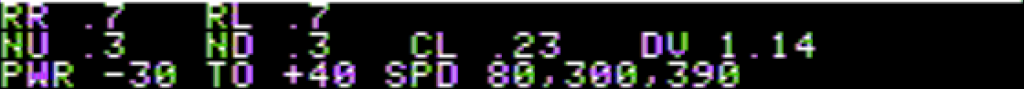

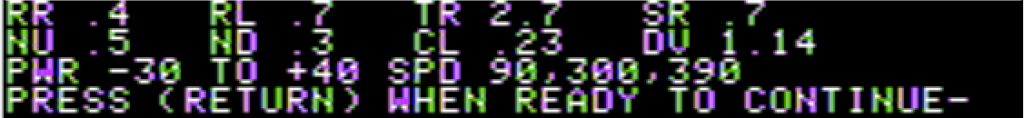

If I “check its capabilities” [CK] I receive the following information :

It says that Rolling Right [RR] or Rolling Left [RL] will take me 700 feet and that moving the nose up [NU] or down [ND] will take me 300 feet.

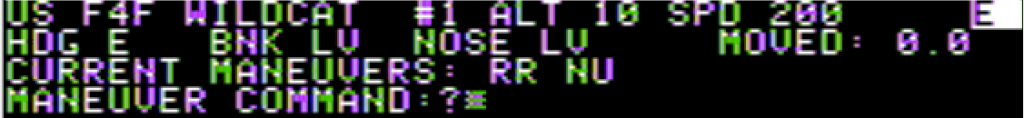

So let’s do two actions at the same time : rolling right [RR] while moving the nose up [NU] :

After having given those orders, I ask the plane to go straight ahead [ST] for any distance, for instance 300 feet.

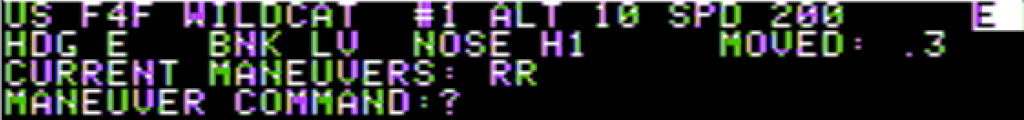

And after I moved 300 feet, my NU order is executed and my nose is now pointing up [H1].

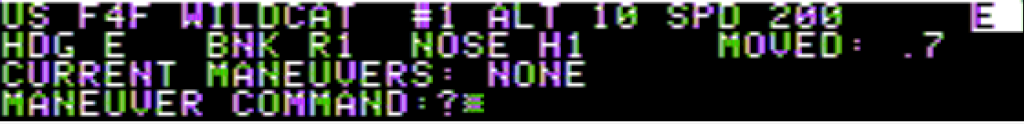

And going straight ahead again until the next maneuver is done, I am now rolled right – I traversed 700 feet out of 2 000 I can plot this turn.

After that , I can check my capabilities again :

Since I am now rolled to the right, I can now turn to the right [TR] or slide to the right [SR]. If I turn to the right, I will not finish the maneuver before the end of the turn, so it will be carried over to next turn.

This seems pretty easy, but this is only because we started from level position. In practice, it can become quickly complex. For instance, quoting the manual :

5.61 Climbing

The nose of your aircraft must be in the H1 or H2 nose attitude in order to gain altitude by climbing. Aircraft in a steep bank attitude, R2 or L2, can only climb if in H2 nose attitude; for them the H2 attitude is like H1 , and H1 is equivalent to LV. The H1 attitude is used for normal climbing, while the H2 attitude is used only to trade speed for altitude in a “zoom” climb, or to enter a climbing half-loop. Inverted aircraft may not be in an H2 nose attitude. […] Aircraft which spend more than half a turn in an H1 nose attitude must climb at least 0.01 kft, unless they are in a steep bank attitude. For purposes of making this determination, time spent diving will offset time spent climbing. Maximum climb ability while in the H2 attitude is increased by an amount which depends upon the speed and type of aircraft.

I am pretty sure you either skipped this text by the 4th row, or read it at least twice before understanding it.

The manual is pages and pages like that, and yes I understand that it is logical that for instance a plane nose down with a strong bank on one side or another [R2 or L2] will turn 45° if it pulls ups, but it is not because it is logical in real-life that it is easy to remember when playing.

Anyway – after you have finished plotting your movement, you have to choose your new speed and by how much you climbed and dived – of course this will all depend on your current speed/altitude/nose orientation, and then it is combat phase.

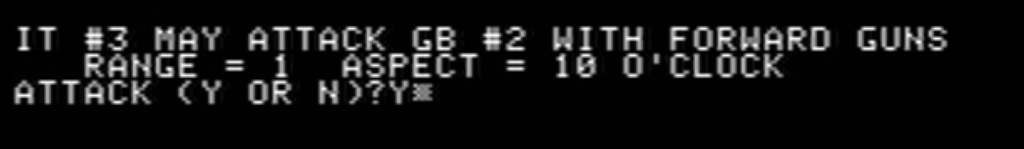

- Combat phase is simpler : anything in front of the gun in a cone of angle 45° and length 2500 feet is in range ; your chance to hit depends on how far it is and on its “aspect” (=direction compared to you). You shoot with all your guns, which have limited ammo. There are also defensive guns (typically on bombers or on heavy fighters) with unlimited ammo. Damage is allocated to wings, fuselage, cockpit and engine. Too much damage and the plane is shot down.

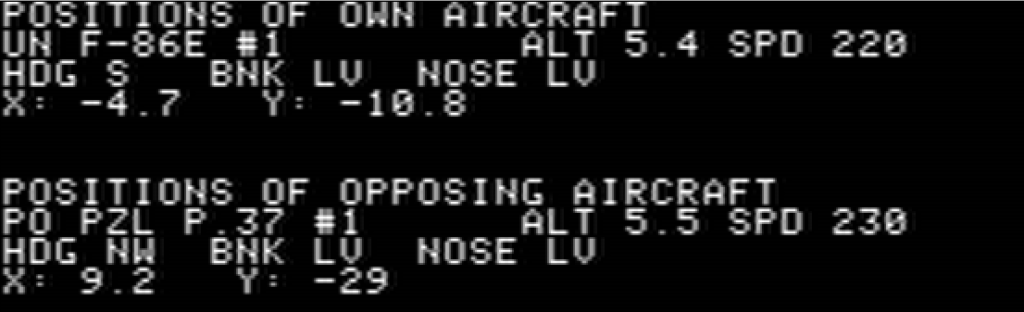

This brings us to the core issue of the game : the fact that you can only shoot at things that are at 2500 feet of you every 7 seconds. Any speed differential of more than 250 mph (typically, two planes in a frontal pass, or just one plane buzzing perpendicularly) and two planes that in real life should be able to shoot each other will not be able to. I tested planes from all the available periods – in early WW2 it is already bad but in the Korean war where the planes can easily reach 600 mph this is just terrible for gameplay. I tried in particular a 2vs2 dogfight opposing Mig-15 to F-86E, after 80 turns (aka 2 hours of my time) of planes trying to shoot each other I just quit.

Add to this that you can only do 45°, so it is extremely common to have 2 planes that are slightly parallel and cannot reach each other quickly because what they would really need is turn 20°. This could have been solved by allowing the slide manoeuvre to move the plane a lot more than 100-300 feet on one side or another.

Long story short : the system was designed to be realistic, but a few design choices made it very unrealistic, and very frustrating.

Score : Average

B. UI , Clarity of rules and outcomes

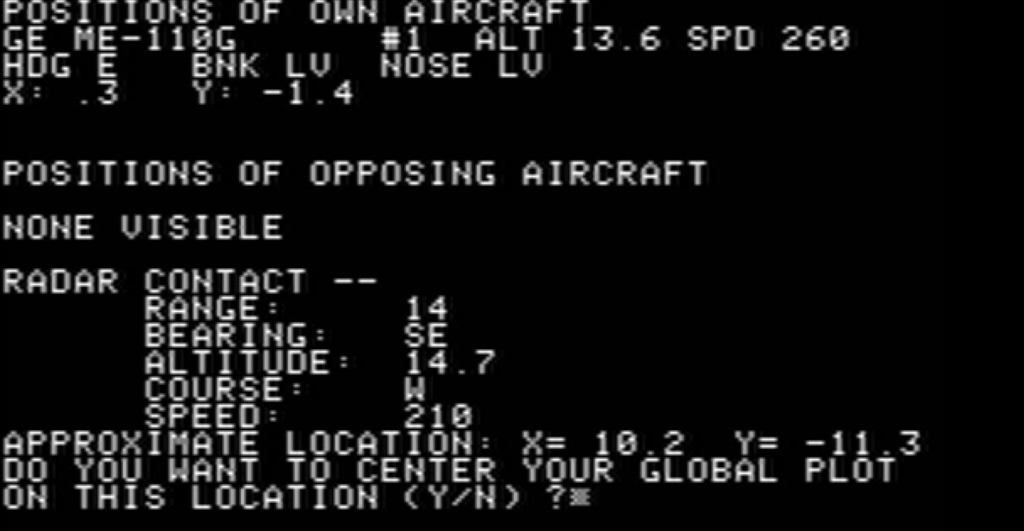

Starting with the UI, as per my AAR the camera is either too far away (for the Global Plot) or too close (for the Tactical Plot). Worse, once in the Tactical Plot you cannot check again the Global Plot or even the Position menu with the list of all planes. Given that in the thick of battle your planes are flying in all directions, by the second or third plane there is a good chance that you don’t remember whether THIS plane should turn left or turn right.

As for giving the orders themselves, it is not helped by the lack of feedback about the movement you already plotted (unlike in Computer Ambush), the lack of grid on the tactical map to evaluate distance (you will have to compare both planes’ X and Y coordinates, if your target direction is at a 45° angle compared to you, you are also going to have to do trigonometry on the fly). It would already be a bad experience in 2D, so now imagine with planes at different altitudes pointing their nose up or down, and not being able to be wrong by more than 2500 feet if you want a chance to hit your target.

As for clarity of outcome, movement is perfectly deterministic, but combat is not, and you have NO idea what are your odds of hitting your target. Given ammunition is limited, this is really not a wise decision in my opinion.

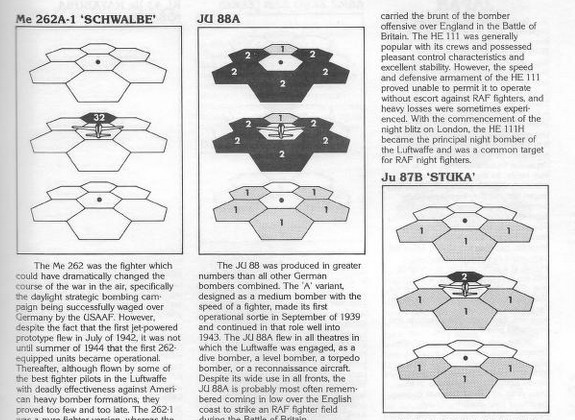

On the positive side, the manual is very complete, even if hard to understand if you don’t have the game in front of you – but then there are training scenarios for a reason. It also includes specific descriptions of each aircraft, including in which direction the weapons can shoot.

Score : Average

C. Settings & Aesthetics

Well, aesthetics is the easy one. Almost none, though I am impressed that I could tell how a plane is banking when it is drawn with maybe 5×5 pixels.

As for settings, as frustrating as the rules are, I must admit that as long as no one is shooting it really feels realistic and immersive, an immersion that is broken every time you actually try to shoot a plane.

There are plenty of more minor rules that add to realism : it is possible to land and take-off, though landing, in particular, has no purpose in any scenario. You can decide that your planes have extra fuel tanks, which will hurt their performance, but let’s be serious you will immediately dump them at the beginning of the battle. The game will tell you whether the crew of a downed plane managed to jump out. You will sometimes lose sight on the enemy (especially when he is behind you), though usually one strong turn and you will see it again. Those are nice and immersive features.

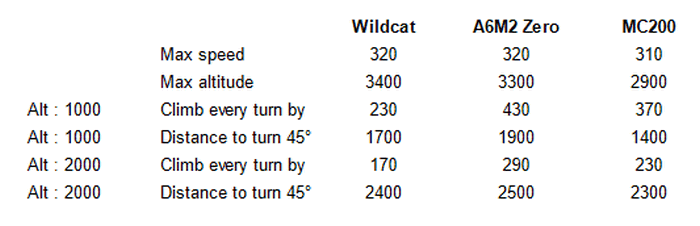

The number of planes is impressive, and they really feel different when you pilot them. I did some tests below (climbing rate and turning distance), with 3 planes, at different altitudes :

Despite having nominally almost the same stats as the Wildcat in the reference card, the Zero is a way better climber, while the Wildcat turns better. As for the MC200, at low altitude its reputation of excellent turner is there in the game, but it loses a large part of its advantage at higher altitude.

The historical / aircraft description section at the end of the manual is a joy to read – I read it all when commenter JKlas uploaded the manual on archive.org, long after I had finished the game. It really shows the attention to detail Merrow and Avery had for their game.

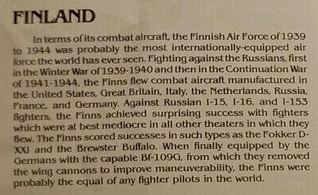

The data disk is on par, with similar historical tidbits about the minor countries :

Minor complaint : the Romanian plane line-up is incorrect, featuring planes they never flew (Dewoitine 520 ? They wished ! Morane-Saulnier 406 ? They escaped that) – but I appreciate the effort. In the 80s Romania was just seen as that country that lost the Stalingrad battle for the Axis, and I suspect material about the Romanian Air Force was extremely rare.

Score : Average

D. Scenario design & Balancing

As we have seen in the AAR intro, there are 5 scenarios :

- Air Race has no specific interest in single player except to test planes, it could be amusing in multiplayer, if you manage to find friends who like this sort of thing, a challenge in itself,

- V1 Interception is something you are only going to play exactly once, and can be considered a training scenario,

- Night Fighting is also a good training scenario, against targets that can defend themselves but do not maneuver too much,

- Bomber Intercept is by far the best scenario, as it forces you to make tactical decisions (go for the bombers directly, or try to shoot down the escort first) and due to the limitations of the game shooting down bombers is easier and more “fun” than shooting down fighters,

- Dogfight is tedious due to how hard it is to anticipate fighter movement. I appreciate that you can create “scramble” mission where some of the planes are on the ground and cannot take-off until their enemy is detected,

You can customize your scenarios freely, with the data disk you can even mix countries (US and Japan against Germany and North Korea ? Why not !)

On the other hand, the scenarios are all pretty dry : no weather, no sun, no ground attack, …

The AI is challenging enough, though I noticed that with the fast Korean War planes it stalled quite a lot. For your WWII games it will not happen.

Score : Average

E. Fun and Replayability

I am sorry to say, but as much as I wanted to like the game, I did not have fun. I played several hours hoping that once I reached some level then I would like the game, to no avail.

And yet I am not a stranger to air tactics simulations, I played and liked Avalon Hill’s 1997 Achtung Spitfire! for instance, but Computer Air Combat is just too arid, you need to calculate too many things on your own every turn, and your best manoeuvres keep getting cancelled by because the rules of the game won’t let you shoot at your target.

It is of course hard to talk about replayability of a game you did not like much in the first place. In my opinion it has some replayability, but without long term objectives, all the battles will kind of look the same after a while, even to the aficionados.

Score : Poor

F. Final rating

Flawed and obsolete. It is a game I respect a lot, but not a game I like.

Contemporary Reviews

Computer Air Combat is a peculiar animal in video game magazines. It is almost always mentioned as part of the story of SSI, or in any compendium of wargames, but good luck finding a review for it – I suspect that most reviewers were in my situation : no love for the game, but deep respect and for this reason not willing to write a negative review for it.

There is one exception though : Dale Archibald in November 1981 in Creative Computing. It takes him several columns to explain how the game works, but it looks like he had fun (he says he had a “mania” for a week, he also ran more ambitious scenarios than me : 5 vs 5 !). He also praises how fast turn resolution is compared to other SSI games (2 minutes only !) and concludes “one of the finest game I have yet played“.

Beyond that, I found maybe a couple purely descriptive reviews of the game (eg in January 1983 in Video Games). And that’s all.

I feel like this game is like Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (or James Joyce’s Ulysses for you Anglo-Saxons) – everyone has heard of it, many like to pretend they played it, but deep down we know almost no one played it and those who did mostly did not enjoy it. In any case, the game sold 4341 copies, a good performance in 1980 – Computer Conflict released at the same time only sold 2433.

Interestingly though, the game was re-released on Commodore 64 in 1985 under the new name “Wings of War“, selling 2909 additional copies.

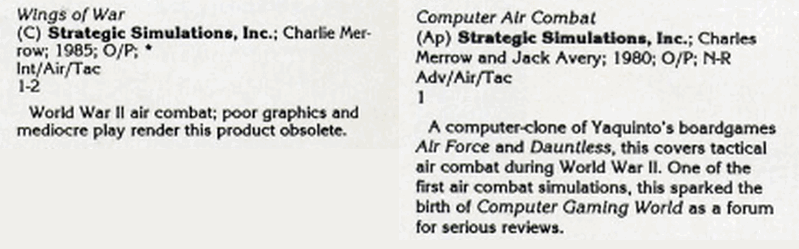

This re-edition under a new name though would give me a final proof that almost no one really played Computer Air Combat ; in their 1991 retrospective on wargames, Computer Gaming World would cover both, with pretty different comments :

So, much like French wine getting panned at international blind test competitions when the label is hidden, the same game received a much poorer review when it wasn’t presented under the revered name of Computer Air Combat.

Charles Merrow and Jack T. Avery carried on working with SSI, and developed Computer Baseball in 1981. Computer Baseball became the best seller of SSI at 45 000 copies, a record that was not beaten until Gemstone Warrior (1984) and Phantasie (1985) sold respectively 52 000 and 54 500 copies. We will see Charles Merrow and Jack T. Avery again with their 1985 Fighter Command: The Battle of Britain – Joel Billings told me it was one of his favourite wargames so I am looking forward to it.