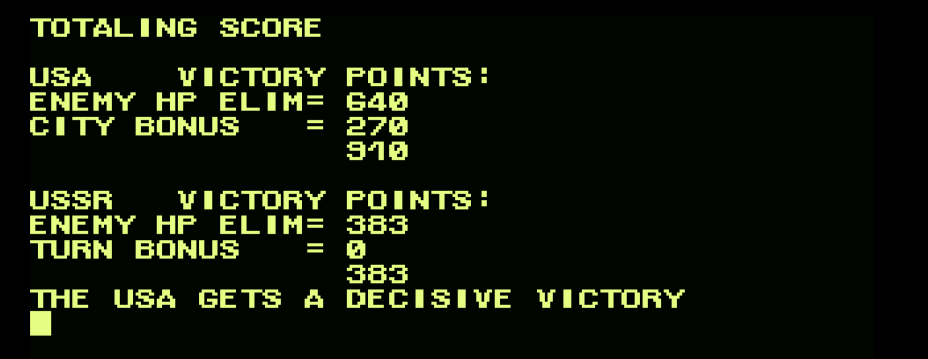

The first episode of the AAR left us turn 7 of 25, so presumably at the end of the first quarter of the game. This second part will include all the remaining turns, and while it was <very> long to play I have much less to say. By the end of turn 7, the Soviets would control 6 of the 9 objectives they needed for a decisive victory, but it was their high ebb. Their immense land forces would be slowly dimmed down from the air, as by turn 6 already I had destroyed 100% of their air force, allowing me to turn every single of my planes into ground support. But let’s check what happened on the various fronts.

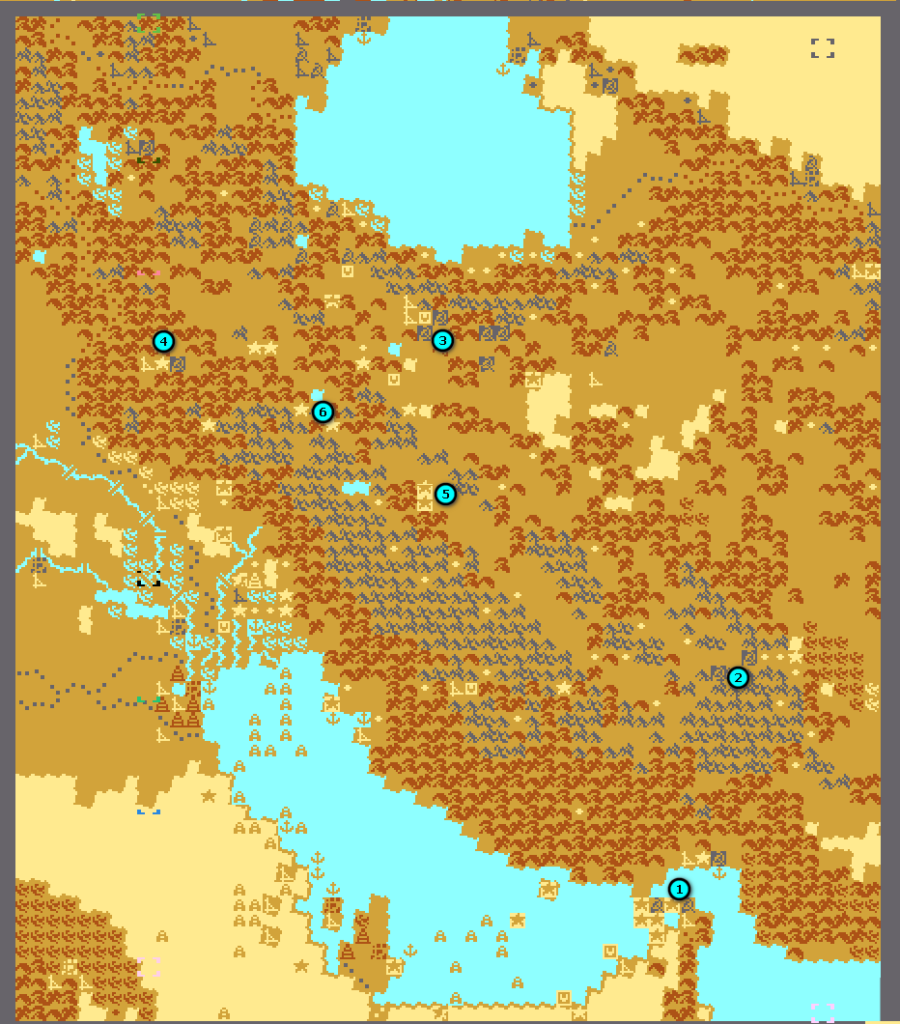

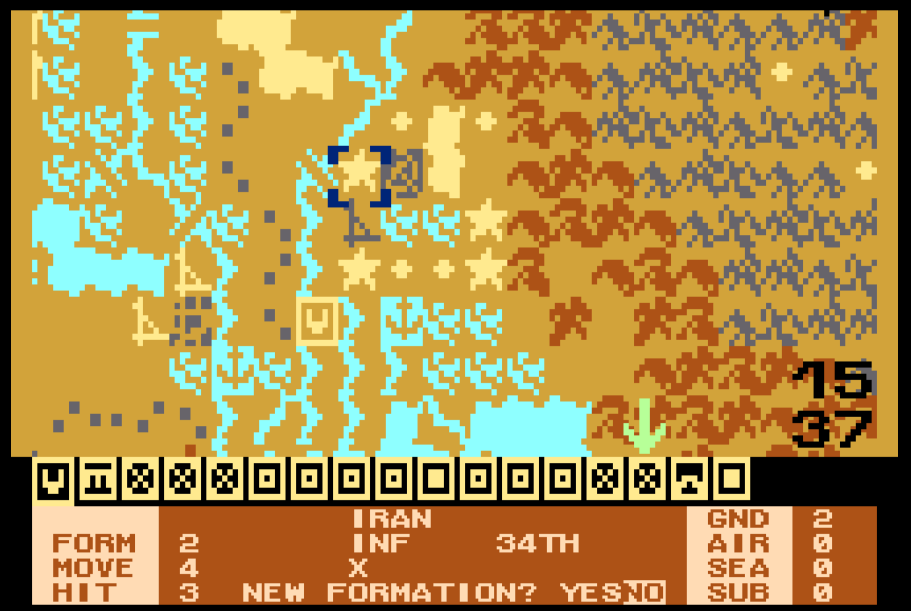

In the South, I spent two more turns destroying the remaining of the Soviet fleet (2 submarines and a nuclear cruiser) [1], after which my seaborne planes (they can’t be transferred to a ground base) focused on the area around Kerman [2]. The large Soviet army which had overrun the city turn 5 had initially headed South toward the Red Sea, but when I retook Kerman turn 9 with a force coming from the North, the Soviets had to turn back and re-siege a well-defended city.

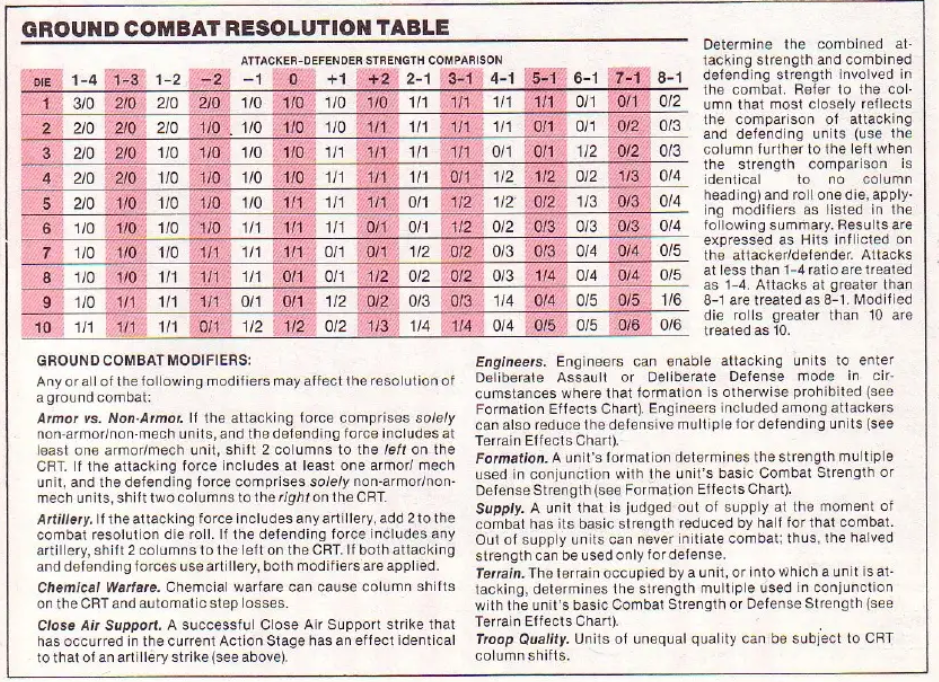

I feel it’s time to explain one of the weird little rules of this game. In Gulf Strike, units always fight at full capacity, whether they have 1 or 7 hit points left. Additionally, air forces cannot destroy units, they can only reduce them to one hit point. This means that by turn 12, after being clobbered from the air, the Soviet army was still very powerful (2 elite units, 2 artillery, 2 air defense), but also very fragile (6 hit points in total), losing combat capacity with every damage received. Meanwhile, the new garrison of Kerman was weaker but sturdy (17 hit points initially), so it could receive damage and fight exactly as well as it did turn after turn. I just had to wait for a luckier-than-average combat roll, after which the Soviet army lost its edge and folded like a castle of cards. By turn 17, the enemy army was so depleted that I counter-attacked and wiped it off the map.

In the North, between Teheran [3] and Kermanshah [4], the Soviets launched an all-out assault… but they split their force into more than 10 different stacks:

This was a tad irritating, because at that point I was using my land-based planes as two huge stacks operating from Kermanshah [4] and Esfahan [5], and attacking one-unit or two-unit stacks with 12 planes was wasting a lot of attacks (since once all the units in a group are reduced to 1HP, further attacks are lost), though at least it minimized attrition received from air defense. More importantly, it made enemy attacks largely ineffective, instead of attacking with a huge number advantage, the Soviets were attacking several times every turn with a mediocre strength ratio against well-entrenched garrisons.

The only reason those small forces were not immediately eliminated was that my air force had to tackle two dangerous situations:

- A strong airborne force moved/landed North-East of Esfahan [5] and started to beeline for the city.

This was, for a time, a worrying situation as Esfahan was far from the frontline and poorly garrisoned. I brought airmobile infantry from Kashan as soon as possible, and evacuated my planes. I shouldn’t have worried: the airborne army split up in 5 different groups just as it reached my city, and I wiped them out in maybe 2 turns!

- As I said, the Soviets broke up all their armies in tiny stacks – all their armies, except one! The one massive army the Soviets kept blew through Hamadan and reached Arak [6] turn 13, which happily could be reinforced just in time by those troops freed by the defeat of the Iraqis in the South-West.

This army was huge, and with two artillery received 2 times +2 on the dice roll for combat resolution.

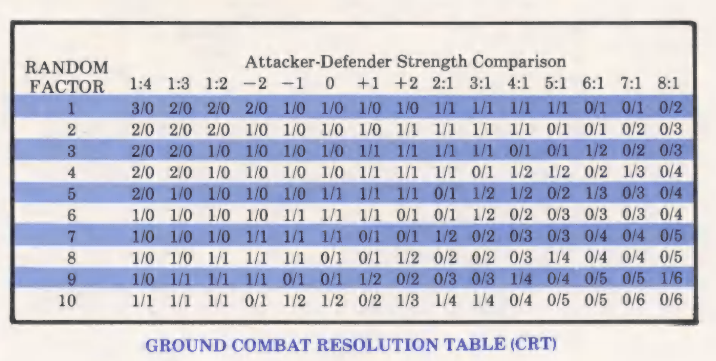

Immediately after having depleted the airborne army, I focused my attacks on that group. However, it had a lot of HPs to remove, and the sheer number of units providing air defense there makes it costly in planes. Reckoning that my garrison has 52 hit points of Iranian, American, Saudi, Koweiti and Emirati units to chew through and that it was inflicting, at best, 4 hit points by turn, I re-allocated my planes to first reduce to (almost) nothing all the other stacks. I only returned to that army turn 17, and turn 19, all the enemy units in that massive army were down to only 1 HP. This is where the +4 in the dice roll given the presence of enemy artillery helped me: “10+” on the combat result table removes 4 hit points on my side, guaranteeing a kill. Of course, there were still 11 units to chew through this way, and I destroyed the last element by a final assault the last turn of the game.

Meanwhile, after having destroyed every other Soviet mobile army by turn 19, I counter-attacked in all directions. The objectives were defended by weak garrisons, and by turn 23 I had recovered the last objective (Zanjan).

I even had the luxury of destroying the Soviet garrisons in Caucasus and Turkmenistan with my airmobile infantry, destroying the last one turn 24.

This means that when the game ended after the 25th turn, there wasn’t any Soviet unit left on the map. It’s hard to imagine a more decisive victory.

Ratings & Review

Gulf Strike, by Winchell Chung, based on a design by Mark Herman, published by Avalon Hill, US

First release: December 1984 on Commodore 64 and ZX Spectrum

Genre: Combined Operations

Average duration of a campaign : 6+ hours with warp mode during enemy turns

Total time played : 6+ hours

Complexity: Medium (2/5)

Final Rating: Obsolete

Context – In a surprising twist, we need to continue a story I thought we had closed more than two years ago. After the demise of SPI and its takeover from TSR, most SPI designers were either let go or simply fled the scene. There had been qualitative differences between Avalon Hill and SPI wargames, imperceptible to outside observers but well-known to their core audience: Avalon Hill was game first and simulation second, focused on playability/accessibility whereas SPI was the opposite, all about simulation at the expense of playability. Eric Dott, the owner of Avalon Hill, was all-too happy to address this orphaned sub-niche by having his own in-house SPI-lite, and along with Mark Herman, one of these émigrés from SPI, he created Victory Games as an autonomous subsidiary of Avalon Hill. Herman, an experienced game designer who had been with SPI since 1976, delivered exactly what Dott expected.

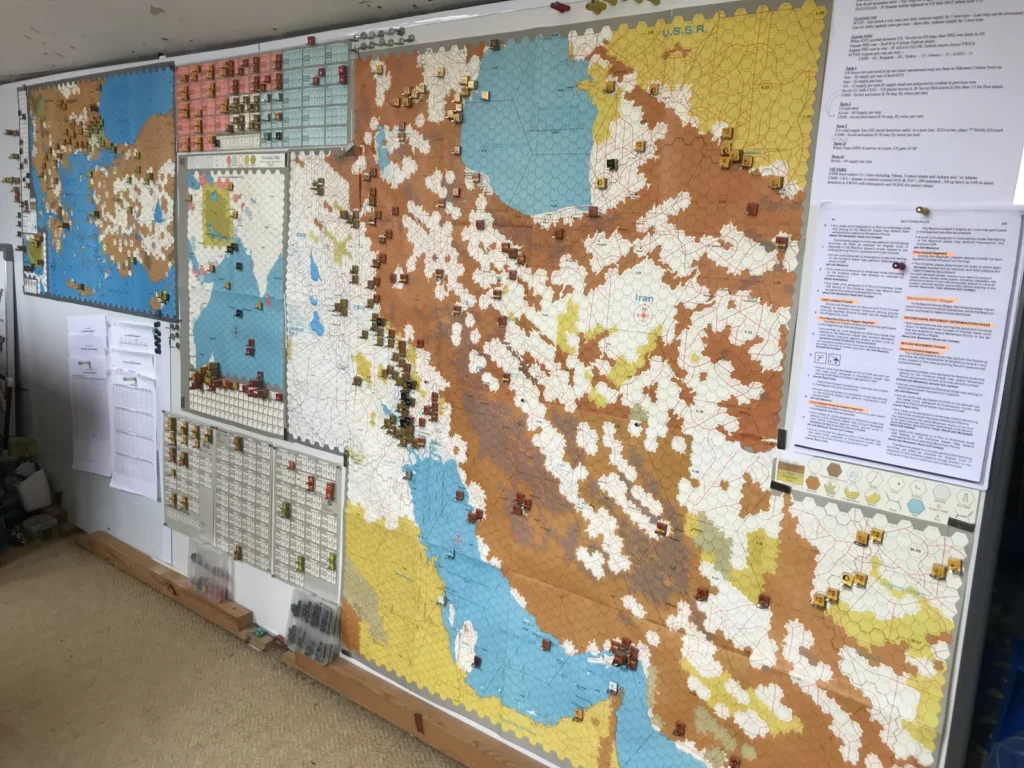

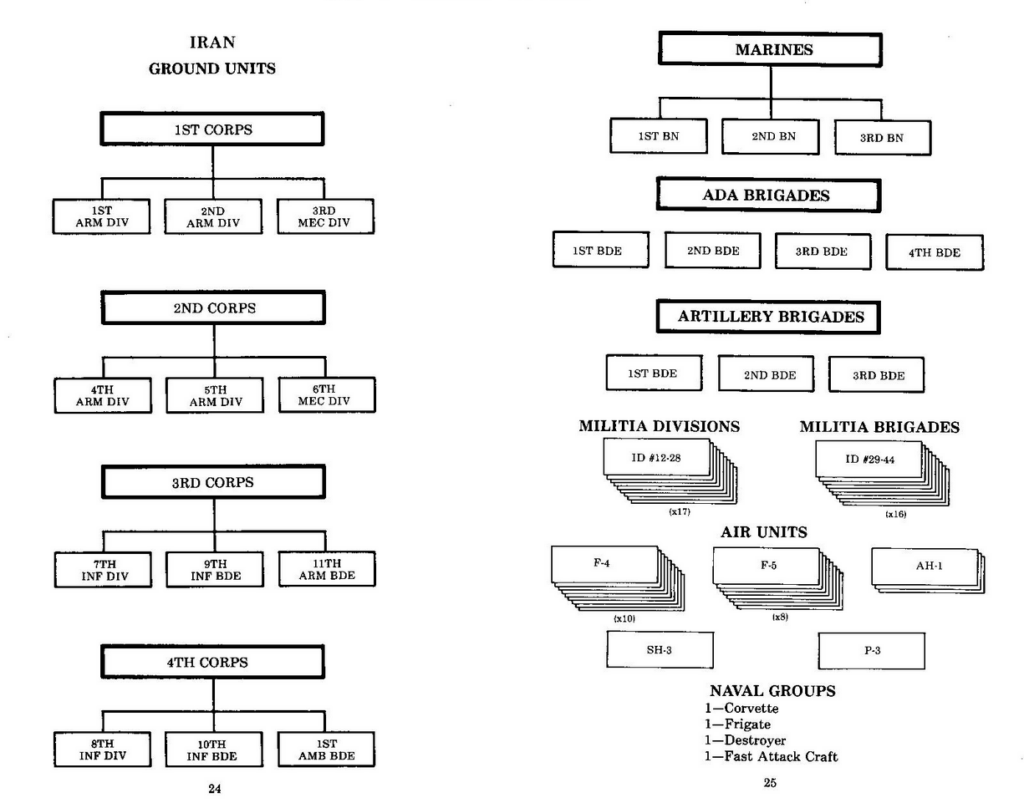

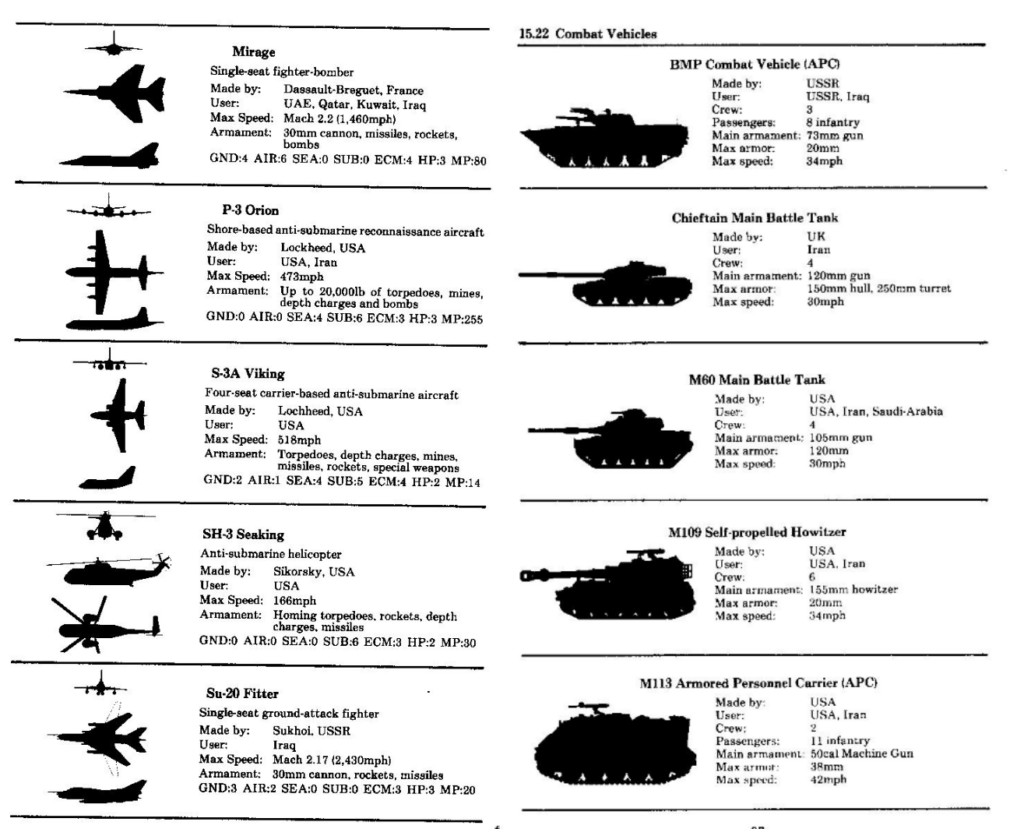

Victory Games’ first production was Herman’s Gulf Strike, a realist yet playable (for veterans) simulation of a superpower conflict over Iran and Arabia. The game is reputedly complex, featuring in particular two map layers (strategic and operational) and over 900 unit counters of all types and countries. The ruleset is “only” around 40 pages long, but it has a lot of depth (supplies, unit breakdown into smaller component, air detection/interception…), a complexity compounded by the incredibly large number of options available to the player given the speed and range of the air units.

I made fun of the Iran-USA alliance in the video game, but the board game includes several scenarios, including the historical Iran-Iraq war, an Iran-Arab States war or the Iran+US vs Iraq+USSR scenario featuring in the video game. Sales number are always hard to pin down, but the game must have had some success, as it received additional scenario in Avalon Hill’s magazine The General, and then two later editions: a second one in 1988 (using the same cover as the video game) and a third one in 1990 which capitalized on the Gulf War:

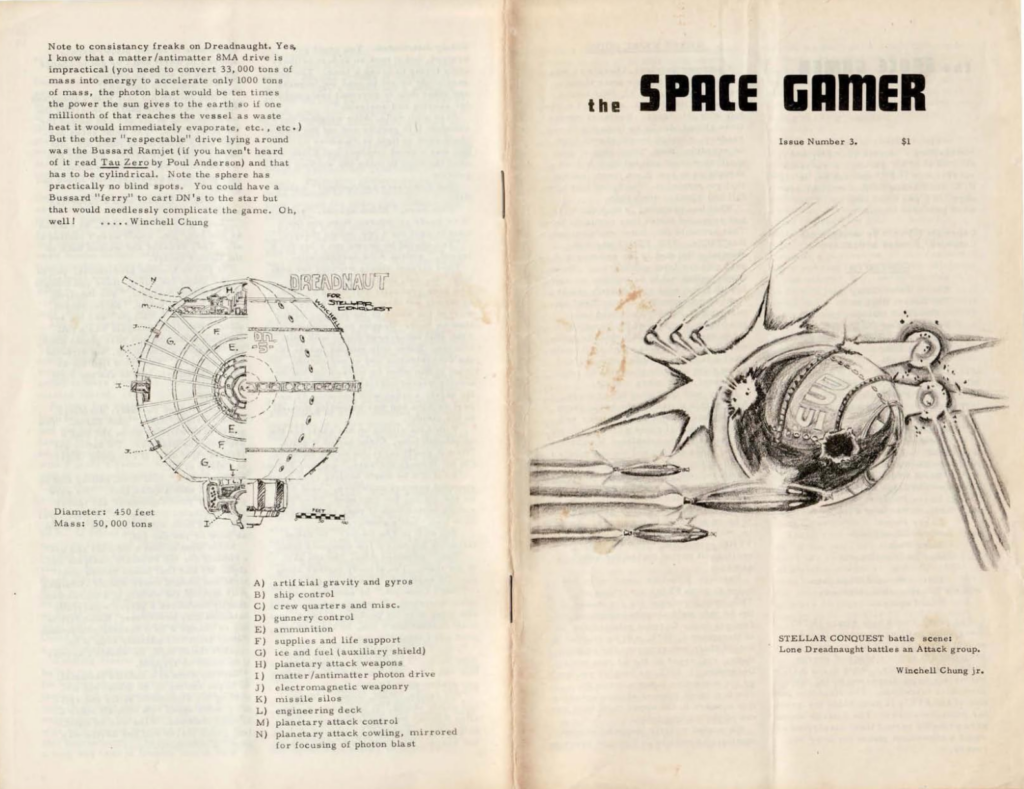

The programmer of the computer version of Gulf Strike, Winchell Chung, ties together a lot of my previous articles that I did not know needed tying together, and shows how small the milieu of wargames was. Chung always liked boardgames, but what he really loved was space. Back in high school in 1974, Chung saw an ad for Metagaming Concepts’ Stellar Conquest, a board game by Steve Jackson of special interest for this blog. As a customer, he received a copy of Metagaming Concepts’ ascended newsletter: The Space Gamer, along with a subscription form. Of course, Chung returned the latter, adding a small doodle in the margin. Metagaming Concepts answered back, and requested more of those sweet sweet doodles – they also published the one they had already received in the second issue of the newsletter. Chung obliged, but sent fully-fledged artworks, making the cover and back of the third issue.

Chung kept sending his art, and remained featured in most of the early issues of The Space Gamer. When Steve Jackson looked in 1976 for an illustrator for his upcoming game on future tank warfare, he simply commissioned Chung and sent him the rules and an NDA. Chung took the concept and ran with it, designing the iconic look of the OGRE with the immense frontal tower and the two eye-like main guns on the front – a look on which cardboard, figurines and video game 3D models would all be based on.

This links Chung to a second game we covered on this blog, but we’re not done yet. After finishing high-school, Chung enrolled in the University of Southern Maine for a degree in art, but continued to work for Metagaming Concepts. It is there that Chung learned to use a computer, first because he had joined a computer-mediated play-by-mail game where turns would cost half-price if you punched your own computer punchcard, and after that because he wanted to calculate star coordinates for a 3D galaxy map project. Chung still finished his art major in 1980, and after a short stint at a professional software company called Estimation Inc., he applied in 1982 at the computer division of Avalon Hill. After showing his TRS-80 skills during the interview, he was recruited and logically assigned to work on Atari, a computer he knew nothing about .

Chung’s first task was porting games made by others into the Atari, which he learned to use thanks to Chris Crawford’s manual De Re Atari, and then quickly moved up the coding ladder. He started with Atari ports, for instance the pretty fun Nukewar and the pretty terrible B-1 Nuclear Bomber, before moving to master versions of games, like Free Trader, which he must have loved, and more relevant to our interest Paris in Danger, a Napoleonic multiplayer-only strategy game I still plan to play some day. During this era, Chung did not forget to do what he loved best: he published an article called “Math for Space War Games” in the Avalon Hill computer division newsletter, playtested various titles, mostly wargames or space-related and finally illustrated the manuals of several titles he did not work on.

He had the final Avalon Hill prestige break of reaching the coveted status of designer when he was tasked to port Gulf Strike.

Traits – I have a lot of negative things to say about the game, so let me first say what I liked and what contemporary players loved: in 1984, War in Russia was the only game that could be compared to Gulf Strike in terms of scope and ambition, and even then it had a much simpler air model and no naval warfare. As much as I am going to write about the terrible parts of Gulf Strike, it was in 1984 one-of-a-kind. Chung clearly loved the topic, as showed by the number of pages in the manual devoted to displaying the order of battle of the various countries, an information that’s absolutely useless (there is no chain of command and units from different nationalities work perfectly together), though like a few other features here and there may indicate cut content.

Indeed, Chung had been under strict instruction to do a computer port and not an original creation, so he had to cram as much as possible of the original ruleset in the limited memory of the Atari. Chung kept only one scenario, removed the strategic map and all the political and logistical aspects; keeping land operations (combats are very similar to the boardgame, including the effects of posture), naval operations and a simplified air model.

I never played the board game, but one problem that arose in the video game version is a major discrepancy between the damage you can expect to deal (even on the 8-1 column, the average damage is 4 – and in normal circumstances you’re going to deal 1-2 damage) and the health of units (3 for a brigade and 7 for a division). Given the lack of supply system, the exclusively defensive objectives of the Iranian-American and units fighting at 100% as long as they are not destroyed (another simplification compared to the boardgame)f, the game quickly turns into a series of stalemates around the objectives, where large forces slowly chip at each other every turn – at least until the planes are involved.

I like the design of the air game (specifically the choice between running missions and interception), but here again the simplification should have triggered a massive rebalancing that did not happen. In the board game, air power is decisive but also difficult to use (supply consumption, detection issue, interception, long-range AA) – in Gulf Strike it’s a hammer that will bring several units to 1 hp every turn, because once you’ve destroyed all the enemy interceptors (around turn 6 in my case) you have absolutely no reason not to use every turn every single of your planes/choppers to its maximum.

It’s a good moment to mention that the game is not pleasant to play. In addition to the lack of icon diversity on the map (everything is either a star or a hammer & sickle), there are many little inconsistent quirks that make the game frustrating. To take a few examples:

- You can check the content of an enemy stack (if adjacent to one of yours) during the movement phase but not during the air phase, which happens after the computer has moved – hopefully you’ve committed to memory which stacks were depleted and which ones were worth bombarding,

- You can cancel land movement if you made a mistake, but you can’t cancel air attacks,

- You can move land stacks, but you can’t move naval stacks: every ship must be moved individually, and there are a lot of them – at least by turn 8 I had no reason to move my ships any further,

- You must select air wings for a mission individually, and this up to 3 times by turn (no “take all button”), but you can’t detach ground units from your armies easily – it’s either “take all” or “one by one”.

Individually, those issues would be irritating enough – together, they made the game incredibly longer and less fun than it could have been, particularly when I knew I had won the game (around turn 8) but still had to spend 15 minutes every turn turn just giving repetitive orders (typically select each plane and send them to their target, three times every turn).

As a final note, Gulf Strike probably also pays the price of a weak computer opponent. The AI is unable to put pressure on the naval front, wastes its planes early in the game and splits its forces into ineffective mini-stacks. Against a solid human opponent, the position of the Iranian-American player is probably less comfortable: I reckon that the Russian player can snatch several objectives in the Red Sea early on, forcing the Iranian-Americans to take risks with their air force and air mobile infantry to defend the objectives in the North of Iran. Additionally, both players presumably keep a large number of interceptors on alert, only launching ground attack missions when absolutely necessary. Finally, the Iraqi-Soviet player is probably able to bypass strongholds to attack where the Iranian player defended the least, so the campaign must be significantly more mobile. Still, the UX issues remain, and the fact that the Iraqi-Soviet player can move second without the constraints of a zone of control must have been maddening.

Did I make interesting decisions? Yes, but only in the very first turns on plane allocation. However, even then, the time-to-meaningful-decision ratio was awful.

Final rating: Obsolete. I really liked the theme and the ambition, but it’s only fun in solitaire for the first 3 or 4 turns of the first try.

Ranking at the time of review: 84/174 – Gulf Strike was at its release more impressive technically and thematically than the 4 earlier Gary Grigsby monster wargames, but it was also a worse game in solitaire. However, I surmise that Gulf Strike is much better than Grigsby’s earlier games in multiplayer (except maybe War in Russia) due to the freedom of movement on the map and the mind game allowed by the air rules.

Reception

Gulf Strike received a good number of reviews, most of them noncommittal. For instance, Russell Sipe concludes a descriptive review in Games Magazine (December 1984) by stating that Gulf Strike offers “an interesting ‘‘what-if’’ game that we all hope will never happen in real life.“, with similar vibes found in Mark Bausman writing for Computer Gaming World (March 1985) and in whoever wrote the review found in Computer Entertainer (May 1985).

My gut feeling is that two things happened: first, reviewers liked the game less than they believed they should, so they avoided being too definitive in their opinions. However, I also believe that few reviewers actually played the game, or played more than a few turns: a lot of reviews bask at the size of the map and the level of detail of the game and give long feedback on controls, but few have concrete comments showing an actual playing experience. For instance Family Computing describes Gulf Strike in January 1985 as “[taking] hundreds of hours to play, yet is never slow and is always completely involving“, whereas Rick Teverbaugh writing for Ahoy! in August 1986 parrots the marketing blurb, including the decidedly absurd claim that “it takes 1 to 5 hours to play“. I am also disappointed by several Bausman’s comments and particularly this one about combat resolutions: “the tacticians among you may find that the optional combat-by-combat resolution provides the tactical feeling you are looking for” – I think Bausman misunderstood the manual and did not bother to double-check in-game.

Someone who I am sure played the game is Dr Jones F. Stanoch, who reviewed the game for Antic in July 1985. Stanoch mentioned issues that should be obvious to anyone playing the game (for instance the problem with the Soviets moving second without ZOC), though unlike me he still loved the game (“I thoroughly enjoyed playing this game. Because of its complexity, I don’t recommend Gulf Strike for anyone unfamiliar with wargaming. But to a wargamer, I cannot recommend it highly enough.“). Obviously I don’t share his love for the game, but as I said earlier I understand it. As flawed as Gulf Strike was, it brought something new to the market, and its many flaws probably didn’t matter as much, because there was quite simply nothing else with the same scope or the same theme.

Until I play Paris in Danger, that’s the last time we will encounter Winchell Chung. After Gulf Strike – which Chung described as more commercially successful than the other Avalon Hill games – Chung was tasked with a Guderian-themed game. However, Avalon Hill’s computer division shut down before the game was complete, and Chung found himself looking for another job. He did not have to look for long, but would never return to video games. Don’t worry for him, he seems to have had one of the most satisfying lives of the developers we’ve encountered so far: around 1995 he launched the website Atomic Rockets, a popular resource for hard SF writers dedicated to discussing how anything cool in space is also completely unrealistic, from “stealth in space” to “those ladders on the side of the typical SF rocket of the 50s”. I jest, but it is a very bingeable website investigating the tiniest tropes of space SF which explains alone one day of delay of the present article – did you know for instance that opening an airlock in space to get rid of an unwanted visitor does not photogenically violently expel the latter in deep space? However, this explains only a small part of my delay, and I am afraid I will carry on being slow for the foreseeable future.

Sources for Winchell Chung’s biography

This interview with Jeffro’s Space Gaming Blog was a key-source for the beginnings of Chung with Metagaming Concepts

This interview with ANTIC The Atari 8-bits podcast was a key-source for Chung’s career within Avalon Hill

Chung also testified about how he came to create the concept for the first Ogre on Steve Jackson’s site.

3 Comments

Excellent as always! The sea at the bottom of the map is “the Gulf”, either the Persian or Arabian depending on what side of it you’re on.

Logistics and supply really do matter, and are things that computers tend to do well, as it’s often paperwork and calculation. Without them you get strange results, like infinite air power or ammunition!

Looking forward to reading Atomic Rockets.

The Atomic Rockets guy, here, on this very blog? Astonishing! The website is well worth the read – just as is every entry by our dear Scribe. 🙂 I’m glad that I was able to read about Gulf Strike, and almost equally glad that I didn’t have to play it. 😀

Ahh, Ogre.

*looks at the tabletop game on the shelf*

How long until we reach an adaptation? 1986? *sobs*