Part of my series on national beginnings: Spain – Argentina – Uruguay – France

Note: Given how my earlier articles on the beginning of French computers were far from the “purpose” of this blog, I decided to consider them a prequel and make this article its own self-contained article comparable to the one on Spain, Uruguay, etc...

In the middle of the 70s, most observers could confirm the failure of the French ambitious Plan Calcul (1966-1974), after the incredibly costly effort to create a champion national of computing had petered out. However, less flashy but no less ambitious aspects of the Plan Calcul had been unheralded successes – first among them the focus on training: from short and technical vocational colleges to long and theoretical Maîtrises. The focus on computer science even went down to High School, with the creation of a High School diploma focused on programming (Baccalauréat H). The exact volumes are hard to consolidate, but by the early 70s, the French educational system was churning out computer technicians and scientists several orders of magnitude above the pre-Plan Calcul. The governmental impulse, the surge in the number of specialists and the general zeitgeist accelerated the computerization of industry and services. With the mainframe computers being the private turf of the State-supported CII (merged into the CII-Honeywell-Bull in 1975), new initiatives focused on smaller computers.

The first microcomputer (1973-1977)

In the late 60s, one of the prides of the French tech was Intertechnique, a company initially founded in 1951 to import American parts for the plane-maker Dassault and which had, over time, acquired an expertise in building hi-tech electronics for the French air, space, and nuclear industry. However, one of its engineers, André Truong Trong Thi, had been disappointed by Intertechnique’s refusal to move toward miniaturisation which he saw as the future. In 1970, he left to create Réalisations et Etudes électroniques [Electronic Deliveries and Studies], or R2E, taking with him the Head of Sales of Intertechnique, who of course brought some of its customers with him. Finally, Truong quickly recruited some of the best engineers from his former company, among them the specialist in electronics and (mini-)computing François Gernelle.

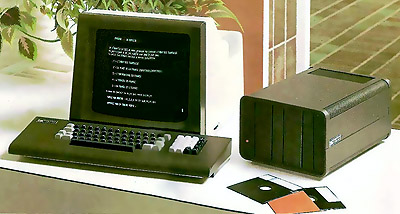

As the name implies, R2E was initially a service company: it helped its customers with either existing computers or custom-built electronic devices. However, Truong had had flair with the timing: the first microprocessor (the Intel 4004) had become available in late 1971 and the Intel 8008 followed less than one year later – a development that was followed closely by Gernelle. In 1972, R2E was contacted by the Institut National de Recherche Agronomique (INRA) to find a way to calculate evapotranspiration: the solution had to be transportable (presumably for the collection of data), reasonably sturdy and ideally cheap so the INRA could buy several. Those were challenging specs that would make an engineer balk (“make it innovative, reliable and cheap – also you have 6 months“), but Truong had an idea: what if he offered a general-purpose hardware bundled with a specific-purpose software (the evapotranspiration calculator) and two BUS for flexibility, and in this way increase the margin by re-using the main hardware for future contracts? R2E signed the contract in July 1972 for a December 1972 delivery. As the story goes, Gernelle and three other engineers worked 18 hours a day to deliver the computer (almost) in time: they had to do everything, both hardware and software, as nothing existed. In January 1973, R2E finally delivered the first device to the INRA: the Micral computer. In April 1973, the Micral (retrospectively called Micral N for “Normal” when other models were released) was commercialised.

At 8500 Francs, the Micral N was more than 5 times cheaper than the cheapest mini-computer on the market: for reference it was the price of a 4K Apple II at its arrival in France 4 years later. This allowed R2E to initially market the Micral as the first of “a new generation of mini-computer whose principal feature is its very low cost“, though it still addressed its traditional customers – industries and labs – to which around 100 machines were sold in the first year. By 1974 however, the novelty of the Micral had dawned on R2E, and it pivoted to calling its series of products (the Micral N, the improved Micral G and the Intel 8080-based Micral S) micro-computers: devices which could do anything a mini could do, and then more – office computing, for instance. The success of the Micral and the apparition of a new greenfield did not escape other French entrepreneurs, and since micro-computers were so much easier to make than mini-computers, other microcomputers appeared quickly: Gessix’s G1000 (1974), MBC’s Alcyane (1975), even LogAbax (the one of the Couffignal machine), which set up shop on the Champs Elysées to sell their LX500 in 1978. However, none of those companies targeted individual users: they were all work and no play. For gaming on personal computers, France would have to wait.

A melee of micros (1978-1982)

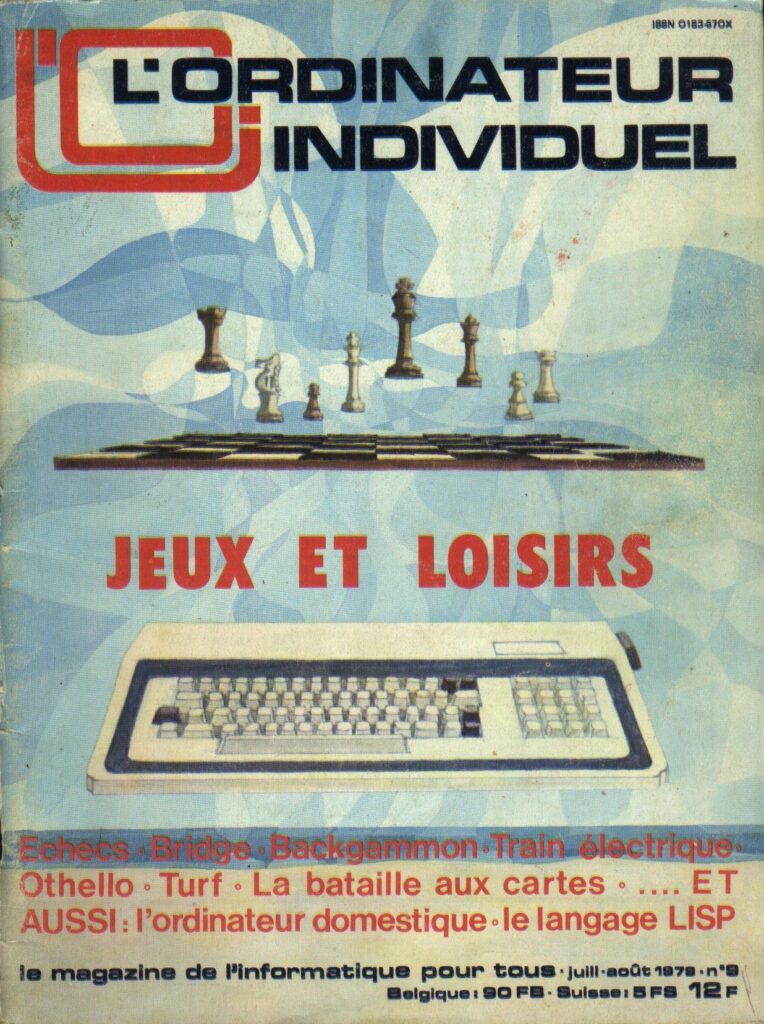

Everything needed for a computer and gaming explosion was set up in 1977 and 1978. The 1977 Trinity was available in France within a few months of their US release: the Apple II in September 1977, the TRS-80 and the Commodore PET in Spring 1978. Just like in USA, the TRS-80 could rely on the RadioShack network (called Tandy in France) while the other computers were sold in the first computer shops, with Computer Boutique in Paris generally described as the first specialist one in September 1977. The first two magazines on personal computing were also launched in 1978: the pretty technical Micro Système in September 1978 and the more accessible L’Ordinateur Individuel in October 1978.

Despite this situation, computing and gaming did not actually take off in earnest before 1982-1983. An official report from the Agence de l’Informatique states that at the end of 1982 , there were 170 000 micro computers in France, compared to the 750 000 in UK and 220 000 in West Germany (twice more by capita). The main reason was probably that in France, computers were serious stuff and games were rare and far between. Micro Système and L’Ordinateur Individuel typically published in every issue one type-in game, sometimes two and more often none. Even the platform-specific magazines (Pom’s for the Apple and La Commode for the Commodore in 1981, Trace for the TRS-80 and Ordi-5 for the ZX81 in 1982) barely mentioned games. To my knowledge, there was no equivalent of David Ahl’s 101 BASIC Computer Games in France either. There weren’t even reviews of games in those early computing magazines – you would find more of them in non-computer magazines like the game generalist Jeux & Stratégie and the wargame specialist Casus Belli.

Then, there was the question of positioning. Most computers did at least one thing wrong on the French market and so failed to receive wide adoption. I am going to use some numbers here and in the rest of the article, but take them with a pinch of salt – all the sources for my numbers are listed at the end of the page.

- The Apple II was sold by Sonotec at roughly the same price as in the US, but at 8000 Francs it was initially too expensive for the French consumer market, particularly for a computer that had not been localized (QWERTY keyboard for instance). By late 1981, Sonotec had sold only between 4000 and 5000 units! The Apple II only started its take off after Apple France replaced Sonotec in 1982.

- Weirdly, the Commodore PET was sold in France by its importer Procep at almost the price of the Apple II (7500 Francs in December 1978) – a bold choice that did not pay off.

- The cheap TRS-80 had the correct price for France, but it was an exclusive of the Tandy shops that were well-established in the North of France (at that time rapidly becoming the French rust belt) and almost absent in the Parisian region (the first shop was only opened in Paris in 1980). Still, the TRS-80 was probably the most successful computer of the Trinity in the 70s, particularly with businesses, but not era-defining.

- Finally, the Atari 400 and 800 were simply absent as they were only introduced in France in September 1982, three years after their US launch.

This left France without a killer platform, and a demand split between a humongous number of micro-computers, including a fairly diverse domestic offer. Most of the French computers were dead on arrival, but the Micral, the Logabax and the Goupil did well or at least decently in the early years, thanks in no small part to contracts with the administration, for instance the “Plan des 10 000 micro [in high school]” (1979). None of those computers were successful as personal computers, and so this first batch of French computers had no role in the history of French gaming.

This created an extremely fragmented market, with the only platform individually significant for personal computing before 1983 being the ZX81, which arrived in late 1981 at a very low price (less than 1000 Francs at launch!) and managed to sell 50 000 machines or more in 1982.

Successive leaders (1982-1983)

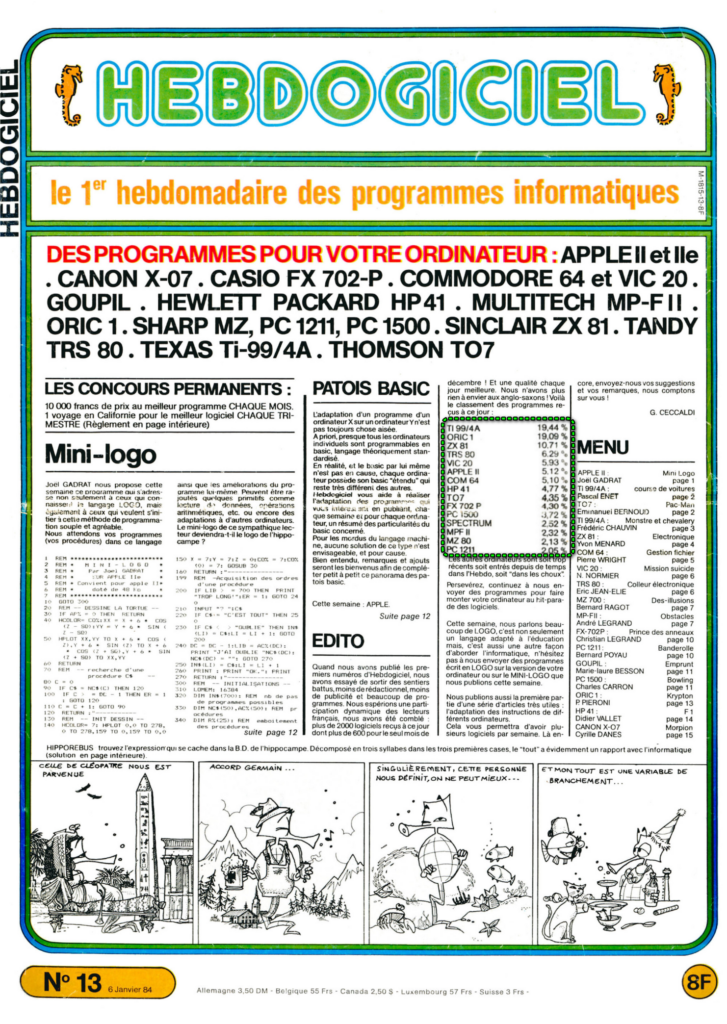

French personal computing – and French gaming – finally took off in 1983 with maybe 200 000 computers sold that year (to compare to 1.3m computers sold in UK the same year!). There were probably two key triggers to this development: the first one is the arrival in France of a gaming culture, with the launch of the magazine Tilt in September 1982 (comparable to the British Crash in terms of tone). Tilt was quickly followed by the short-lived Micro 7 in January 1983, and then in October 1983 by Hebdogiciel, a weekly publication that featured page after page of type-in games sent by the readers. As we’ll see later, this is also when the first French domestic games started to be sold, in a positive feedback loop with the sales of computers.

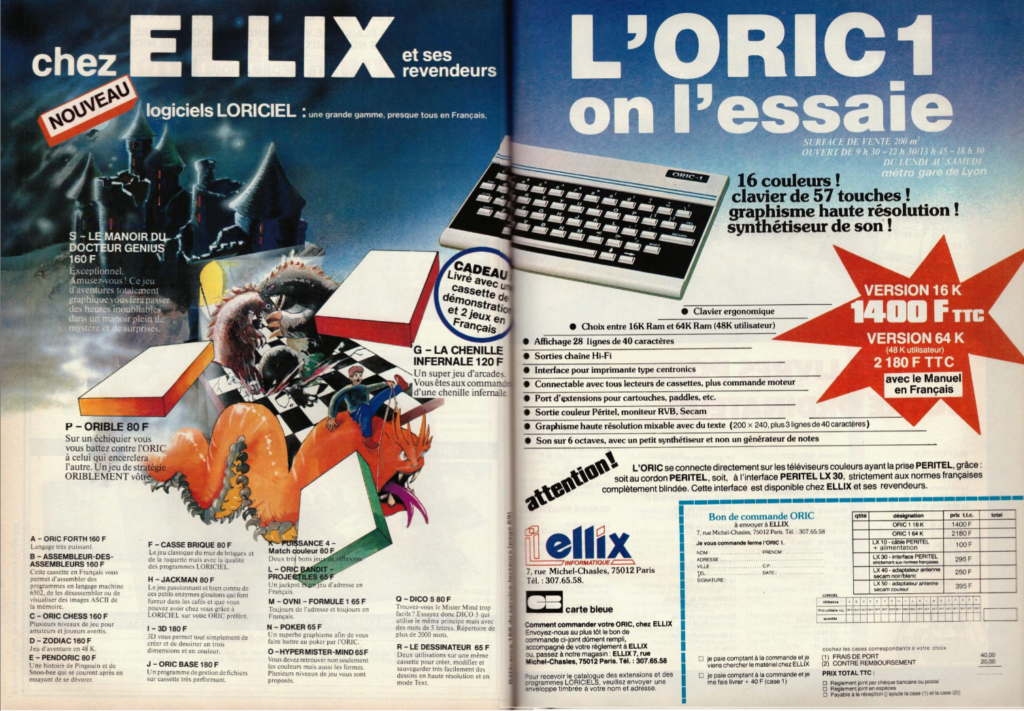

As mentioned before, the ZX81 was the first computer with a significant footprint in France. It continued to have good sales in 1983 and depending on the source, it had sold between 110 000 and 150 000 machines in total by mid-1984. France should then have taken the next logical step and switch to Spectrum – except France didn’t because the Spectrum only arrived in France in June 1983, one year after its British release. By that point, another British computer – the fairly comparable Oric – had been around for a while (January 1983) and snatched the lead. Its success was due to its relatively low-price (2700 Francs) and of course early availability. By 1984, 60 000 Oric had been sold – more than in any other country – against only 30 000 Spectrum.

However, the Oric would not be the star of Christmas 1983, instead an unlikely contender would dominate the last month of 1983: the TI99/4A. Launched in May 1982 at 3000 Francs, the TI99/4A had relevant but not huge sales (around 20 000 between May 1982 and November 1983). When Texas Instruments announced in November 1983 it was leaving the computer market, the computer was massively discounted (1600 Francs so way cheaper than either a Spectrum or an Oric) and so many TI99/4A found their way below the French Christmas trees. When the TI99/4A craze ended in early 1984, 60 000 additional TI99/4A had been sold! Meanwhile, the only significant French personal computer of 1983, the Matra Alice, sold 20 000 machines – same as the Commodore 64.

The stabilisation (1984+)

We’ll finish this chapter with 1984, which really set up an equilibrium that survived until the arrival of the 16-bits in late 1986. Three series of computers absolutely dominated the market, leaving only scraps to anyone else:

- The Apple II, as the efforts of Apple France and its President Jean-Louis Gassée (who eventually replaced Steve Jobs as head of the Macintosh development in 1985) started to pay off: 50 000 Apple IIe had been sold by mid 1984, and according to at least one source up to 400 000 Apple II by 1988, in addition to 300 000 Macintosh,

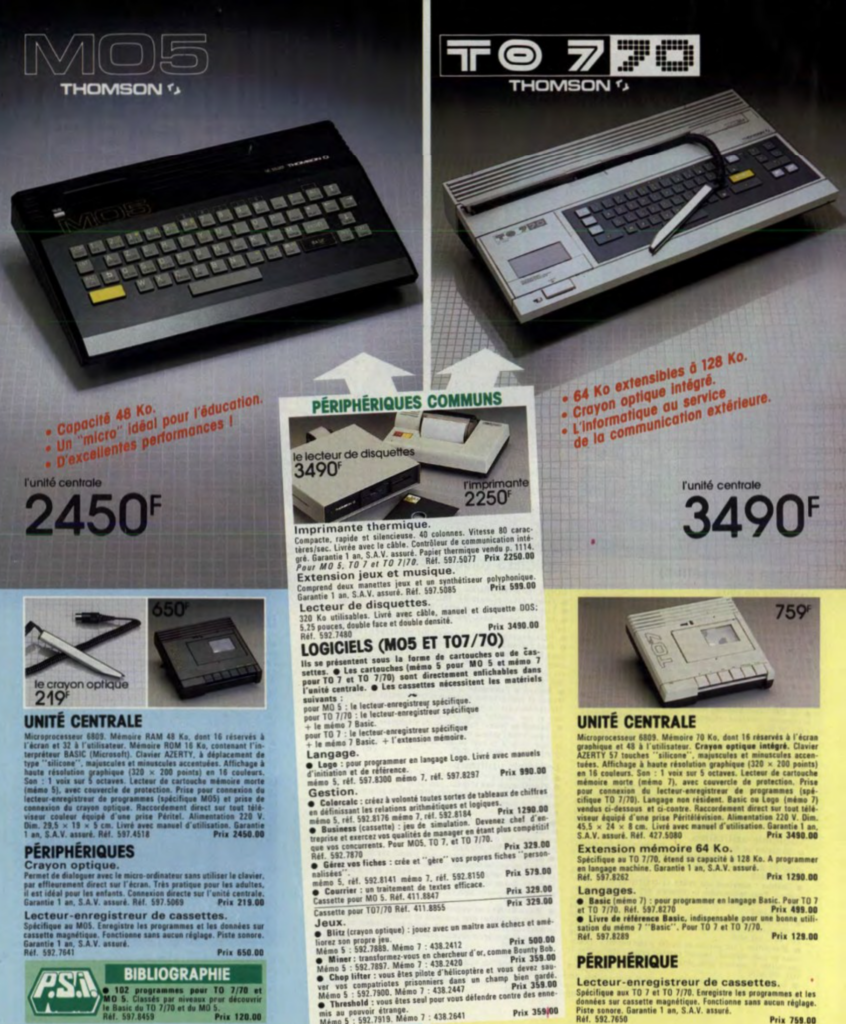

- The French constructor Thomson, with its TO7 and MO5 (dubbed along with a few other marginal computers the MOTO family). The first Thomson computer, the TO7, had been released in December 1982 and was unable to make a dent in personal computing. However, it managed to thrive thanks to orders from schools, in particular the massive Plan Informatique Pour Tous [“Computer Science for Everyone”) launched in 1985 and which equipped 50 000 high schools with 120 000 Thomson computers: an upgrade of the TO7 (the TO7/70) and the specifically-designed MO5, a low-cost TO7/70.

In truth, the choice of Thomson was very politically motivated. The MOTO computers were slow, their graphics lacklustre, their sound primitive, their peripherals often incompatible between MO5 and TO7 and finally the series had barely any software when the Plan was launched. Aware of the situation, the initiator of the Plan had negotiated a deal with Apple to use a made-in-France Macintosh, while some other specialists had recommended using a popular computer like a Sinclair or an Amstrad. However, Thomson had been nationalized by the government back in 1982 and so the contract was awarded by fiat (no public tenders!) to it anyway. The overall result of the Plan is mixed, but for Thomson the plan worked, at least for a time – its computers gained a status somewhat comparable to the BBC Micro as the “serious” “official” computer of France, and so families bought it for their home as well. When Thomson finally stopped doing computers in 1989, 500 000 Thomson computers had been sold.

- Finally, the computer that really defined the mid-80s for anyone who was not a student, a teacher or a hobbyist was the Amstrad. The Amstrad CPC 464 was launched in France in September 1984 and was an immediate and absolute success – it was a plug-and-play computer at a moderate price (4500 Francs, but at the price you had a colour monitor and a tape recorder, which were not included in the listed price of other computers). For anyone who just wanted a computer without having to learn to use one – an unaddressed part of the market thus far – it was perfect.

Estimations on how many Amstrad were sold vary from 600 000 to 1 000 000 by 1988. Whichever number is correct, no other computer could enter the market until the 32 bits: why buy something new when you can have an Amstrad and its games for cheap!

That’s all for the computers: after a short period of Oric (but according to my research, there wasn’t any wargame exclusive to this platform anyway), our period of interest will be dominated by Amstrad, Thomson and Apple II. Now, let’s talk about the games!

The beginnings of French gaming

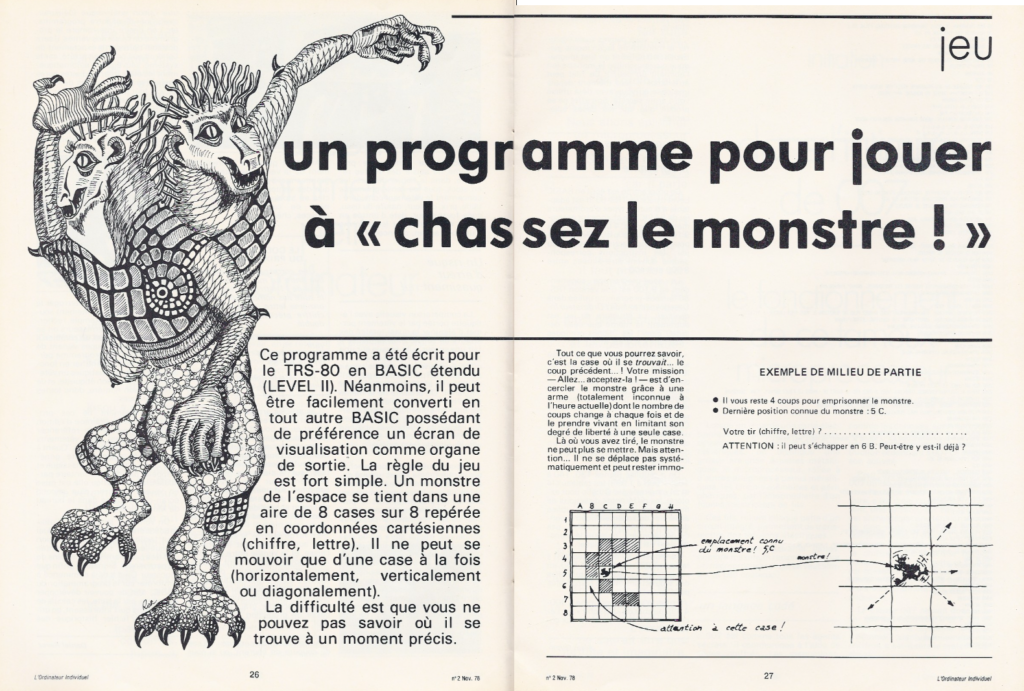

Just like everywhere else, the 1977 Trinity started without games in France. However, while the first American owners of microcomputers quickly enjoyed ports from mainframe and games from the mainframe era, France had no such luck, as mainframe games were rare and often in English anyway. There were early signals that France would catch back quickly: the first issue of Micro Système (September 1978) included an advertorial written by staffers of the Computer Boutique shop and describing a French Star Trek (you could buy it in Computer Boutique!) running on SWTPCB 6800 (you could buy one in Computer Boutique!). As for l’Ordinateur Individuel, after publishing a listing for an Othello game in their first issue, their second issue in November 1978 showcased a French-designed type-in game: Chassez le Monstre [“Hunt the Monster“] for TRS-80 by Alain Girpin. The game is unrelated to Hunt the Wumpus: it is played on a 8×8 grid and the objective is to block the monster by creating walls around it, which is harder than it looks because the monster moves.

Unfortunately for the French prospective gamer, neither magazine doubled down and generally speaking not only 1979, but also 1980 and 1981 were dull for gaming in France. For instance, here is what game listings you could obtain in 1979:

- Four in l’Ordinateur Individuel, including one “original”: a “hunt the submarine” on a 100×100 grid,

- Six in Micro Système including two “original” (a stock-option game and a realistic space travel game), one incredibly ambitious Mastermind (combining hardware jerry-rig AND Assembler – March 1979) and one Nim-cum-machine-learning (July 1979).

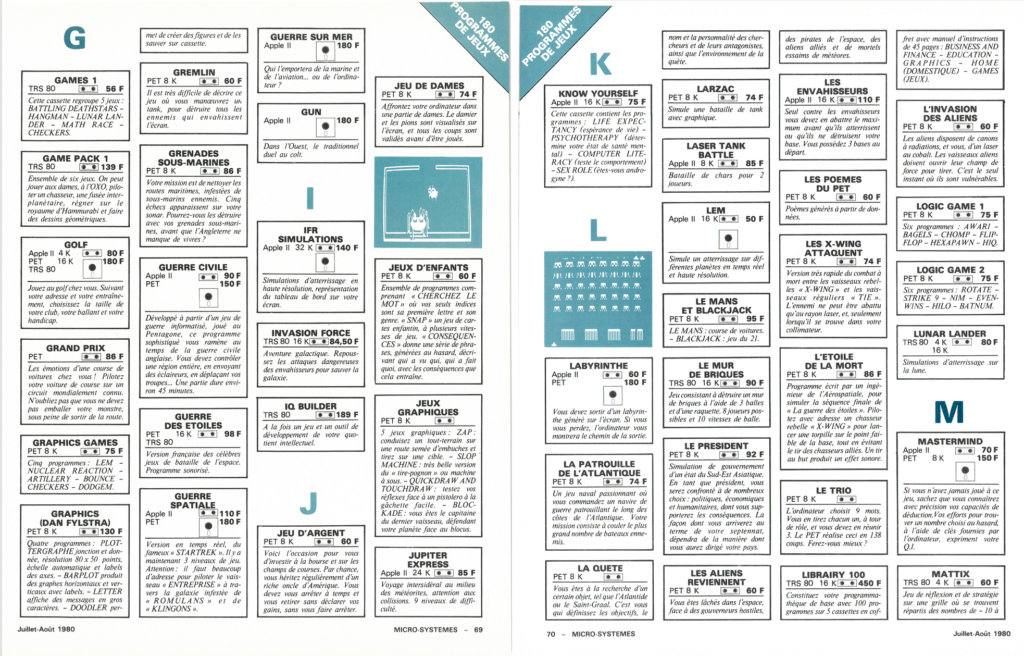

This is was a far cry from what Creative Computing or similar publications offered at that moment in USA, and prospective gamers had to turn to mail-order. The first commercial games were advertised in 1979, so not much later than in USA (1978), and just like there, it started as small bullet points in broader ads about computers, peripherals and software; the difference really is that such game ads were much rarer in France (2-3 per magazine) than in USA. The first games proposed are classics or imports: Chess, Bridge, Othello and of course Star Trek. Over time, the catalogue expanded with more imports, but oh so slowly. in July 1980 Micro Système reported that it had queried the mail-order companies operating in France and counted 180 titles in total, many of them not games in the first place, across all platforms. From my own count and excluding compilations, around 120 of these are really games, including at least 3 Lunar Lander clones, 3 Breakout clones and maybe 6 or 7 Star Trek. The complexity runs from say Temple of Apshai to Hangman.

Slowly, year after year, the number of importers increased and the catalogue of games expanded. By the end of 1982, the offer of games was finally fleshed out, with hundreds of video games, mostly American and British, in addition to clones and the occasional port of French non-video games like the Mille-Bornes or the French popular TV show Des Chiffres et des Lettres sold by the Parisian shop SIDAG. Furthermore, the ZX81 was in late 1982 the first model of computer to have represented a significant percentage of the French installed base, making it an interesting platform to develop from. This is when France was ready for its first French video game companies.

Back in 1979, musician Philippe Ulrich had released a critically successful sci-fi-inspired album, unfortunately at a total loss as it was immediately boycotted by the main radio channel Europe 1 (the lyrics had been interpreted as an attack on its owner) and his record label wasn’t paying him his due anyway. Depressed, he acquired a ZX80 – the only computer he could afford – in the hope of producing a new type of sound. However, there wasn’t a lot of musical range in the ZX80, and Ulrich decided instead to have some fun with the Othello game listed in the first L’Ordinateur Individuel, which he then tweaked and improved until it could beat him. Having succeeded, Ulrich moved to other traditional board games, then to Space Invaders, then to his first creation: Panique for ZX81 (early 1983), a somewhat stale platformer that’s nonetheless the first French commercial PC video game. Having a small catalogue already, Ulrich and his friend Emmanuel Viau founded in April 1983 the first French video game publishing company: Ere Informatique. Ulrich immediately considered himself someone who would find and grow talents, and indeed he himself had a talent for exactly that. Before the end of the 1983, ERE Informatique had published its first game: Marc-André Rampon’s Intercepteur Cobalt. a French-made future air combat simulator. Intercepteur Cobalt was a success in France and paved the way for Ere Informatique to publish more games, but we’ll return to it when I cover its weird ZX81 wargame Rigel (November 1984).

Glossing over the magazine publishing giant Hachette, which launched a few games in May 1984 under the short-lived label Ediciel, we can now move to the second alumnus of 1983. In June 1983, Bruno Bonnell, a salesman at Thomson, had created a video game company called Infogrames to make games for the Ti99/4A. Bonnel had his first games planned for the last quarter of 1983, but that plan went spectacularly bust when Texas Instruments announced it was leaving the computer market, exactly the same day as Infogrames released its first Ti99/4A game Autoroute, a Frogger clone. While the TI99/4A and Autoroute would have a short last-minute burst of success after all, Bonnell had to pivot to a new platform and restart from scratch, but with his funds exhausted. That’s when he met at the main French computer convention (the SICOB) an eager high-schooler from Lille: Gregory Ruck. Gregory Ruck and a few of his comrades had learned to program on a TO7, and eventually had tested their skills by making games based on their favourite movies: I.L L’Intrus for Alien, Troff for Tron and even a Mission Pas Possible that did not make it into a commercial product. Ruck had been sent to the SICOB in the hope of finding a publisher, and since Bonnel was looking for games to publish, Infogrames had TO7 games in its catalogue in late 1983 or early 1984. Many would follow.

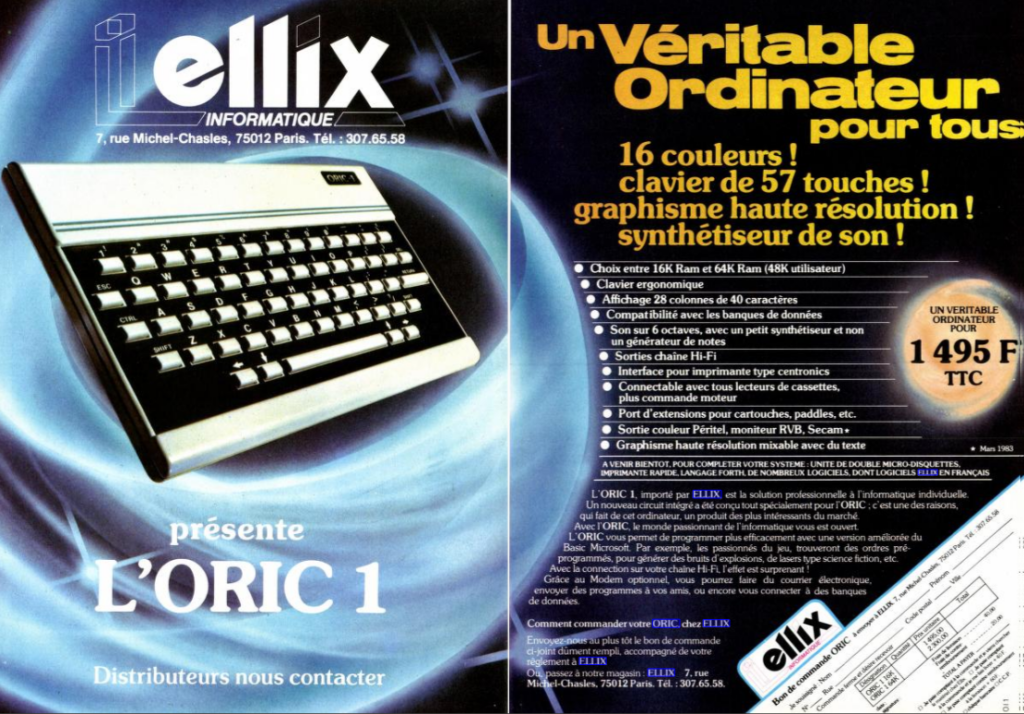

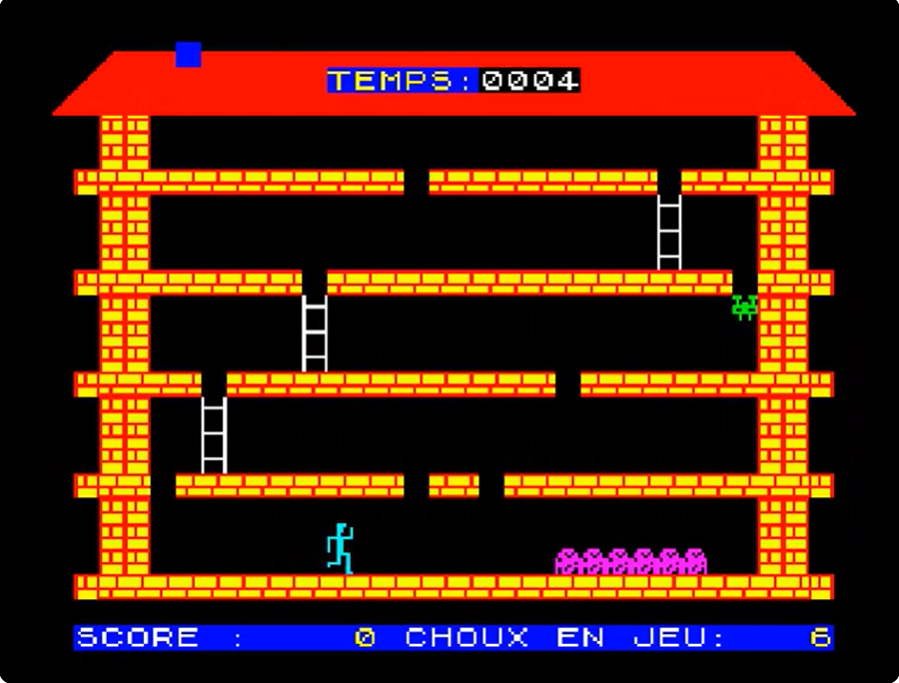

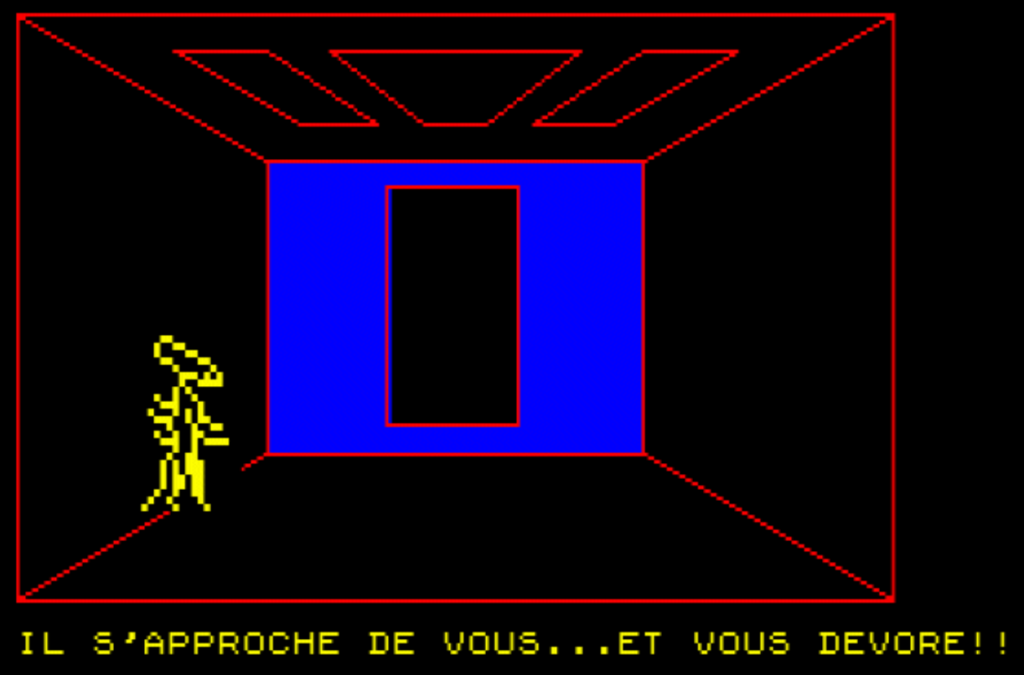

This leaves us with the last French video game company of 1984. Back in 1982, the 22 year-old Laurant Weill had founded the computer store Ellix. As Weill was looking for a way for Ellix to stand out, he heard about the Oric and felt it could be very successful in France. He negotiated a distribution clause with Tangerine in late 1982 and started selling the computer in November and December. However, while he had the killer computer, he also knew it would sell even better with software. Weill did a couple of games himself, for the rest he tapped the many hangers-on of the shop. The first software, unidentified but probably not games yet, were apparently available as soon as January 1983. In July 1983, Elix finally went all in with 17 software for the Oric – including 13 games – under a new brand name: Loriciel. Most of those games are copies of existing designs, but one is a new French adventure game: Le Manoir du Docteur Genius.

Unfortunately for Ellix, this release had a pretty poor timing: in June 1983 Tangerine had decided to sign an exclusive distribution agreement with another importer, even though Ellix somehow continued to sell Oric computers until at least December 1983. Weill, already stretched thin between his business and his studies in biochemistry, decided to separate the software company from the shop (September 1983) and start selling his games outside of Ellix. He made the correct choice: by the end of 1984, Loriciels would have more than 80 software on its catalogue (all of them French-made) and had sold more than 200 000 games.

That’s where we stand at the beginning of 1984, with 3 French companies created in 1983 that would contribute to define what would later be called the French touch. Having covered more than I should have the French situation with regards to computing, I can now return to my coverage of wargames, with the first French wargame: Free Game Blot’s World War 3. It’s a lot less epic than the name implies.

Post-scriptum: I did not mention the Minitel, a French proto-internet using phone connections launched in 1980, but that’s because in that era its offer in games is marginal. An October 1985 article of Jeux & Stratégie lists all the Minitel games it could find, and they are only casino games, traditional boardgames and quizzes, with one adventure game (Le Vaisseau Maudit, now lost media) as the exception. I also did not mention arcade machines, but for the record Le Bagnard (1982), published in the US and Japan as The Bagman, is generally considered the first French “original” video game.

Happy New Year everyone.

Main sources

Une histoire du Jeu Vidéo en France, Alexis Blanchet et Guillaume Montagnon, 2025. This was my main source.

La Saga des Jeux Videos, Daniel Ichbiah, 1997

Informatique pour Tous, Premier Remous, May 1985, SVM #17

Micro-Informatique Française: Les occasions perdues, May 1985, SVM #17

Biographie de l’ordinateur R2E-Micral, ou comment faire exister un « micro-ordinateur » dans les années, Loïc Petitgirard, Technologie et Innovation, 2020. Everything you need to know on R2E and the Micral – English version

Micral User Manual [in English!], January 1974 it’s where it is described as a very low cost mini-computer.

Micro & Crocos: The French home computer market in the 80s

Le Ti99/4A face au marché Français, Fabrice Montupet

Entretien avec Noël Pietri (head of Sales of Texas Instrument France in the early 80s), Fabrice Montupet

Interview of Laurant Weill in Joystick

Sur les traces des premiers jeux vidéo français, William Audureau, 2018

I couldn’t have written this article without the massive work of Abandonware Magazine, a massive database of all computing and video game magazines – it has more than 22 000 issues and is a way more complete database for France than archive.org. Unfortunately, I am not always consistent in documenting which specific issue I found some specific information in.

Source for sales number:

- Macro data (total sales of computers): Une histoire du Jeu Video en France, Micro & Crocos. All 1988 data also come from Micro & Crocos.

- Apple: 1979: Ordinateur Individuel September 1979, before late 1981: Grateful Geek by Jean-Louis Gassée, 1984: L’Ordinateur Individuel, Guide 1983-1984

- Commodore: L’Ordinateur Individuel, Guide 1982-1983 the PET 4000 and the PET 8000, 1983-1984 for the VIC-20, Commodore 64: Micro Système September 1984

- Logabax: 01Hebdo 31/03/1980 for the Logabax LX-500 and here for later models

- Micral: Sciences & Avenir 24 for the 1500 by the second half of 1978, L’Ordinateur Individuel, Guide 1983-1984

- TI99/4A: The article above by Fabrice Montupet and the interview with Noël Pietri

- ZX81 and ZX Spectrum: L’Ordinateur Individuel, Guide 1982-1983 and Guide 1983-1984 and first issue of Echo Sinclair, Micro Système September 1985

- Amstrad: Interview of the CEO of Amstrad France by Marion Vannier by PhenixInformatique