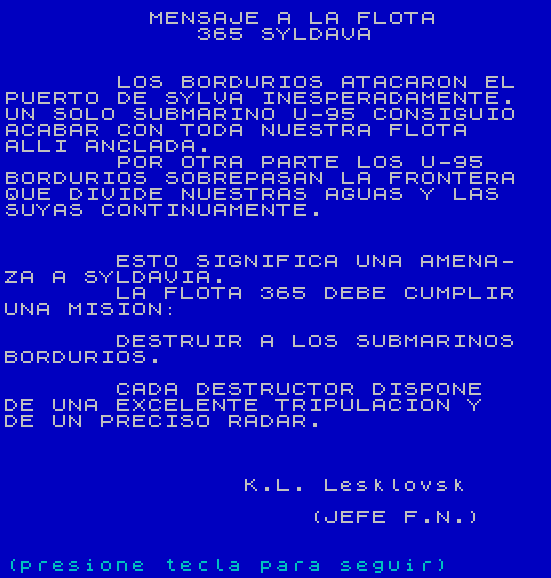

Submarinos U-95 is a minor Spanish game covering a little-known conflict from the Tintin Expanded Universe: the surprise attack and destruction of a Syldavian fleet by one or several Bordurian U-95 submarines. Thankfully, the Syldavians can still rely on Fleet 365, whose mission is now to destroy the Bordurian subs. The caveat is that “Fleet 365” is just one destroyer, which is maybe not that surprising if you remember that the Syldavian population is 642 000 according to a tourist pamphlet found in King Ottokar’s Sceptre.

The game then proceeds to show you the tactical map, whose only important element is the position of the “X”, your naval base. Remember where it is, the game will never show it again.

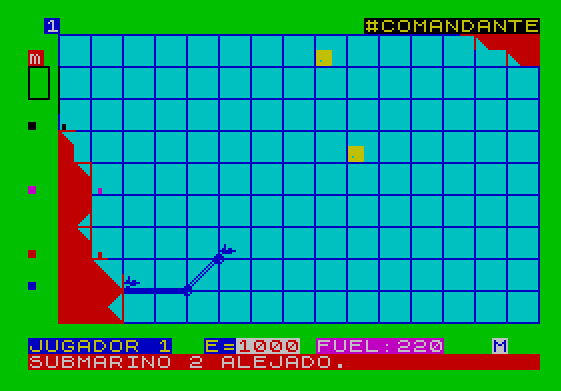

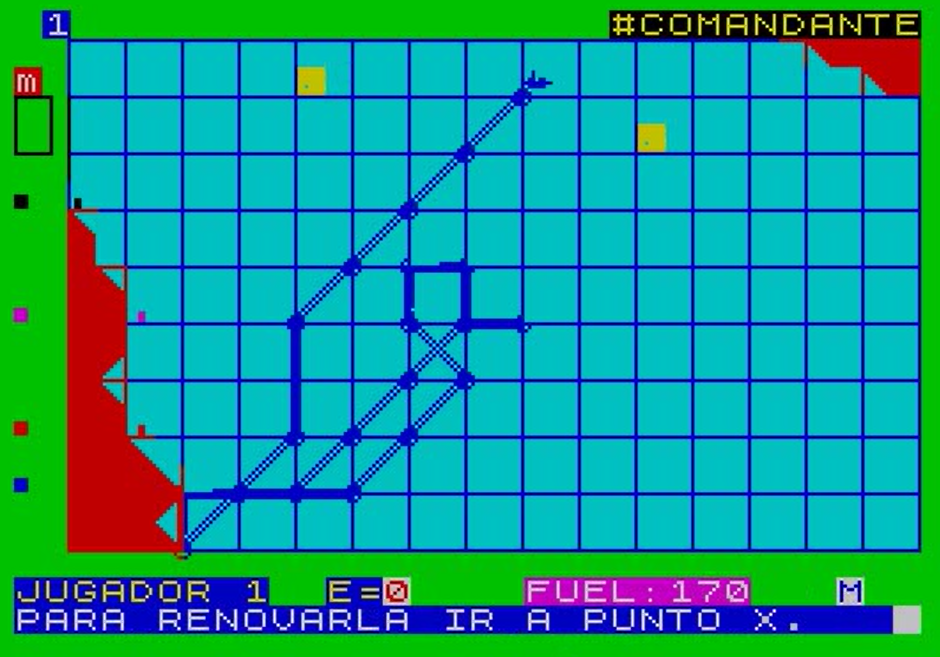

I choose to face two U-95s in solitaire at the Comandante [4/5] difficulty, and the game starts. I have only two options available: use my sonar (which consumes energy), and move. I start with a movement East at speed 2, and then a movement North-East before using my sonar:

The sonar costs 500 energy out of my starting 1500 energy, but that’s fine because that’s the only use of energy in this game.

I move North-East twice and I find myself in range (=1 square away) of a submarine. The combat sequence starts, and it ain’t Torpedo Fire: I must guess a correct number (“depth”) between 0, 1 and 2, so I have one chance out of 3 of sinking the submarine. I miss, and nothing happens.

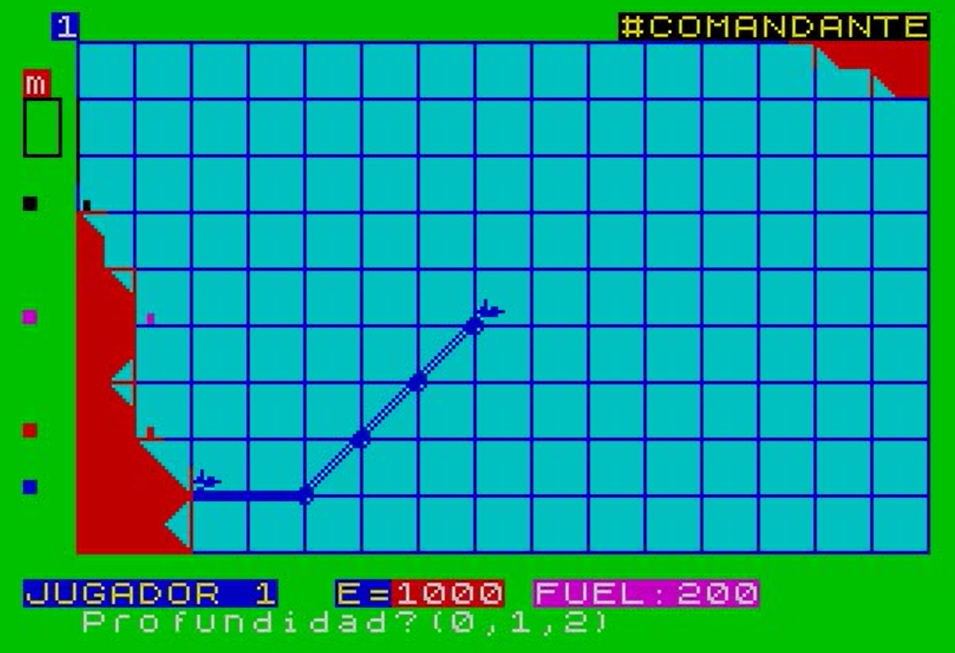

I fail to engage the U-95 again, despite using my radar twice more. The second time, I discover that my enemy moved dangerously close to my base:

If a U-95 reaches my base (the “X” above), then she “invades” it somehow and it is game over. I am not exceedingly worried – the U-95s follow a random walk – but they can get lucky and I need to refuel and re-energize anyway.

Once in my base, my vitals are maxed again and I ping the map again: the U-95s have moved to the North of the map. I get there as fast as possible and scan again: one submarine to my left, another to my right.

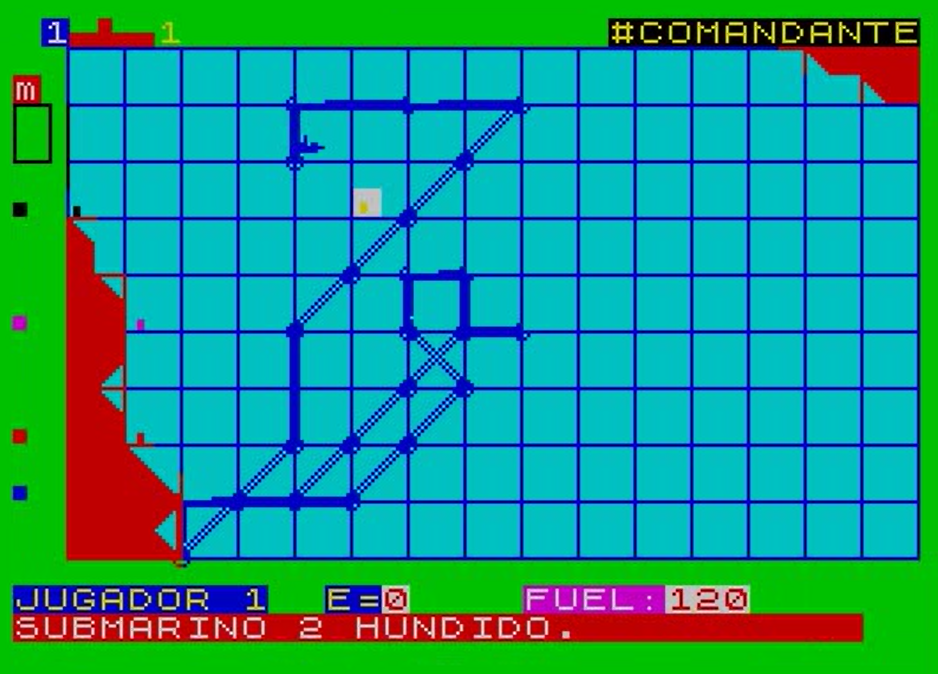

I sail toward the Westernmost submarine, and this time I am lucky and sink her.

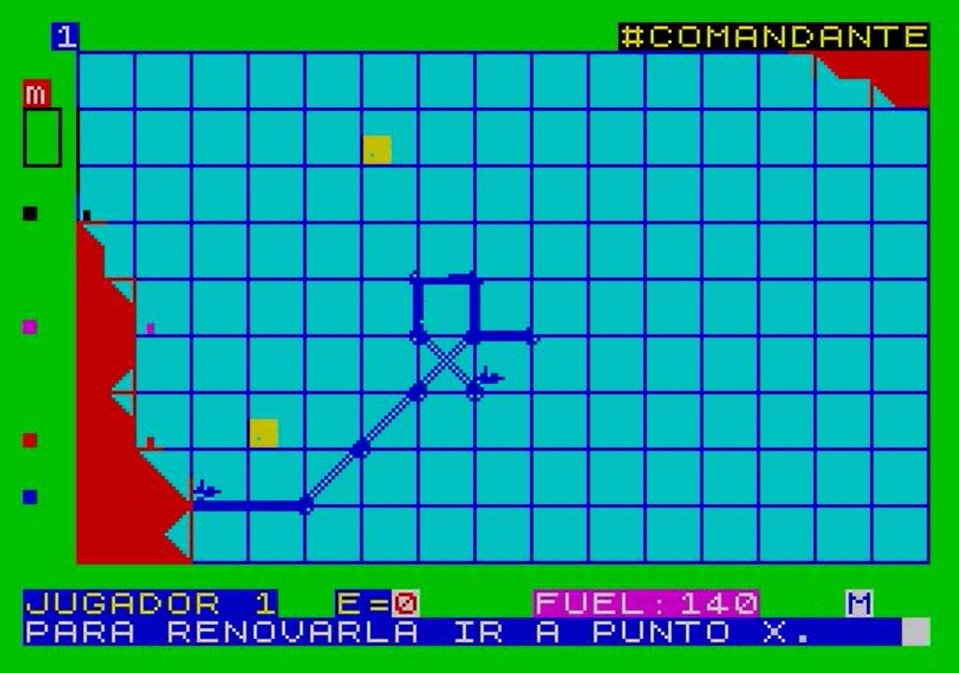

I return to the base to refuel and re-energize, and then catch and sink the second U-95 in Bordurian waters:

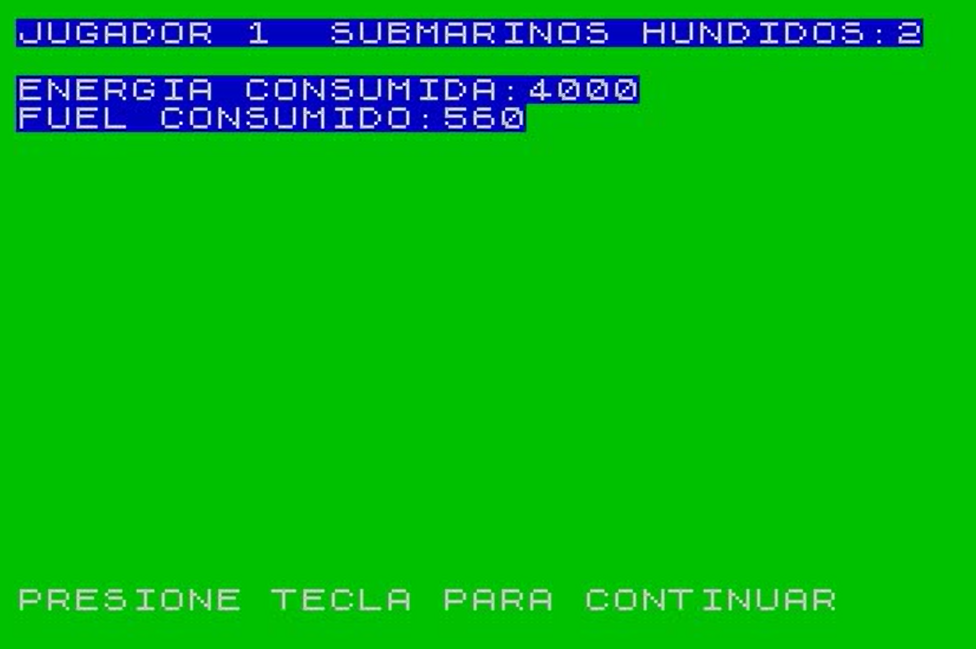

It’s the end, after 10 minutes of pointless “gameplay”.

With a maximum of two actions available at a given time and only one ship to command, Submarinos U-95 is at best wargame-adjacent, hence a BRIEF rather than a full-fledged article. The only feature I did not show is that your destroyer can be damaged, which forces her to return to base before she can attack a submarine again (I don’t think you can lose your destroyer). This does not add anything, because it is as random as the rest: either a U-95 moved unto your position (quite rare due to your longer range and their random walk) or your ship entered a mined tile and was unlucky enough to hit a mine (very low probability). As expected, the implementation of the mines is as shabby as the rest of the game:

- In difficulty 1, no tile is mined

- In difficulty 2 to 4, all the Bordurian tiles are mined, but you have no reason to go there if the Bordurian submarines are not there either,

- In difficulty 5, all tiles in the game are mined, including your base!

That’s all. The author thought there was enough of a game to propose a multiplayer option, in which each player commands a destroyer. Let’s just say there were better hotseat games in 1984.

Juan del Poso, the author of Submarinos U-95, left no footprint neither on SpectrumComputing nor on archive.org; one of my hypotheses is that he had to disappear under a new identity to escape the enforcers of the Hergé estate. I hope he made it.

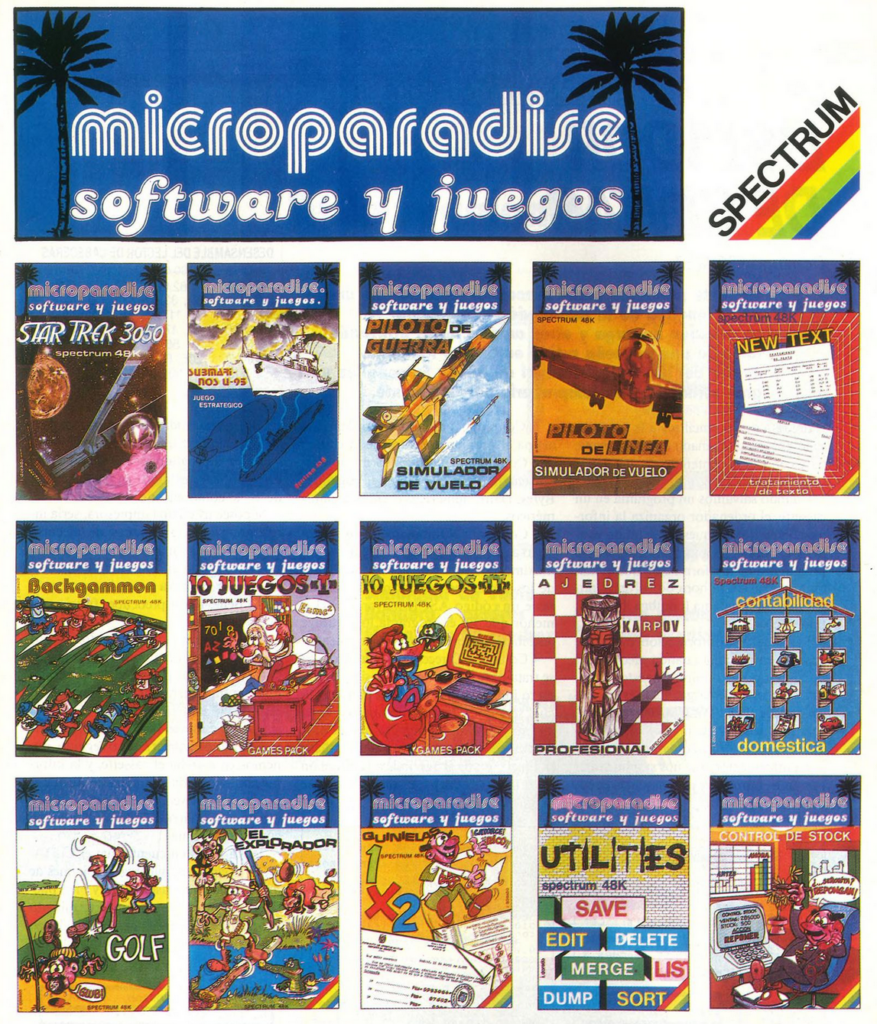

MicroParadise, the publisher, was a short-lived (late 1984-early 1985?) publishing branch of MicroWorld. MicroWorld was a Spanish company established in 1983 or 1984 that tried for a short time to do everything computer-related: computers (they had distribution exclusivity from Amstrad at some point), accessories and video games, both retail and wholesale; and of course with MicroParadise they were publishers as well. This was probably too many rabbits to chase at the same time and a sure way to have no friends in the industry, as they were competitors to everyone. On top of that, Pablo Ruiz of Dinamic, who signed an exclusivity distribution contract with them in 1984, remembers them as disorganized and shady, with a lot of his time wasted trying to get them to pay what they owed Dinamic – eventually Dinamic left them for ERBE. Either their poor reputation caught back with them or they found their niche, because starting in 1986 and based on their digital footprint, they seem to have downscaled their ambition and focused exclusively on the Amstrad. I reckon they have disappeared in 1987 or 1988.

I am now done with the 1984 Spanish games, and I will return to our carriers at war with the rarely covered Indian Ocean Japanese campaign of 1941-1942. Feliz Año Nuevo!