[Color Computer, Picosoft]

– Generals! Have you thought about sending massive waves of infantry – and when I say massive I mean massive massive – at the Germans without being slowed down by those stupid tanks?

General Pershing, Commander of the American Expeditionary Force in Europe (1917-1920), probably, at least according to the Feuer & Gasse manual

After reaching a new height with the Ancient Art of War, I need to cleanse my metaphorical palate in order to be fair to future games – and what better choice for this than Color Computer wargames which, with the unexpected exception of Ark Royal’s Guadalcanal, have been at the minimum stale and more often than not buggy tests of patience. And so I am ready for everything as I approach Picosoft’s Feuer & Gasse [Fire & Gas], their only game that has not been lost to time.

I recently penned a guest post for the CRPGAddict and he introduced my review with a mention of this rule “It’s never a good sign when the game box and the title screen don’t agree on the name of the game.” Well, Feuer & Gasse is off to an excellent start in terms of zeroing my standards, because you need to type Fire & Gas to launch it, and then the title screen welcomes you with a superb mix of German and English: Feuer and Gasse. The notepad samizdat of the manual offers another hint that this game will fully achieve my purpose for it, because the historical background reads like it was pulled straight from the souvenir shop of John J. Pershing’s hometown museum. World War I’s leadership on both sides, you see, “was distinguished mainly for its mediocrity“. But then Pershing, after a visit to the front, had “radical” recommendations: “that the standard division be doubled in size, that troops be trained to drive the enemy into the open, and finally that field commanders be given the initiative once engaged in combat”. As one can imagine, “his recommendations constituted a scathing repudiation of the premier military strategists in Europe“, who presumably hated the idea of training troops.

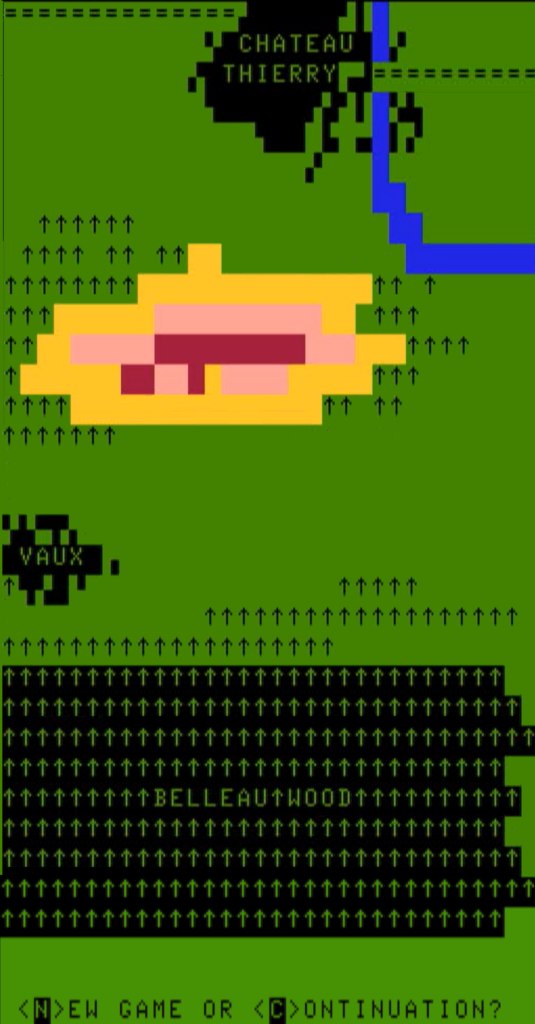

When the Germans launched their final offensive against Paris in 1918, the Allies fell back despite a stubborn defense. This is what triggered the events displayed in the game: “The German 7th Army under General von Boehn, confident of an easy victory, decided to rest and fortify their advance position in Belleau Wood prior to the final push on Paris.” – but little did they know that Pershing and his Americans had come to turn the tide of the war.

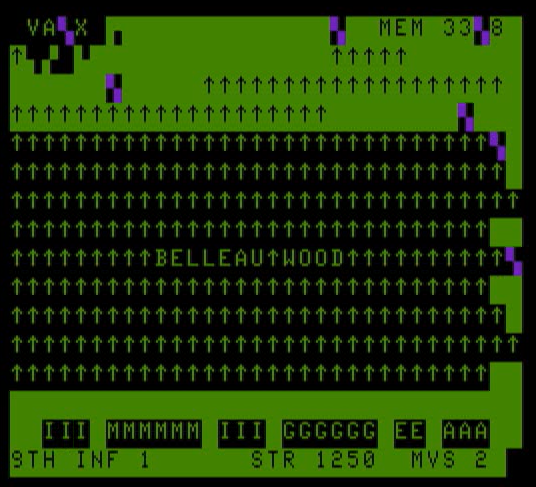

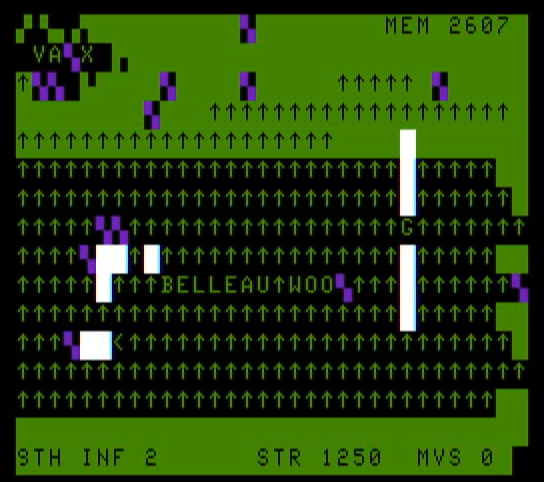

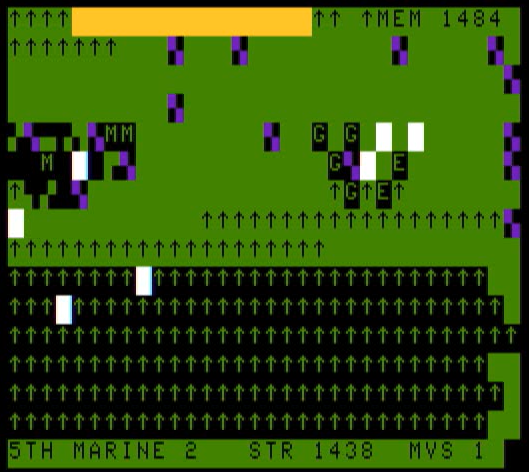

The player starts at the bottom of the screen, with:

- 6 units of infantry (speed: 2, strength 1250),

- 6 units of Marines (speed: 3, strength 1500) – they’re plain better than infantry because of Marines exceptionalism,

- 2 units of engineers (speed: 4, strength 1000),

- 6 units of machine-gun (speed: 2 strength 1100, weak attack at range),

- 3 units of artillery (speed 2, strength 500, powerful attacks at range, no movement on hard terrain)

The speed of my units is going to be a problem: entering a forest tile takes between 1 and 3 movement points, so infantry sometimes fail to even move when marching in the forest and stand in place for the whole turn. Happily enough, just like in Ark Royal’s many earlier games (for instance the unimpressive Waterloo), once a unit has entered a tile, other units can join it for only one movement point.

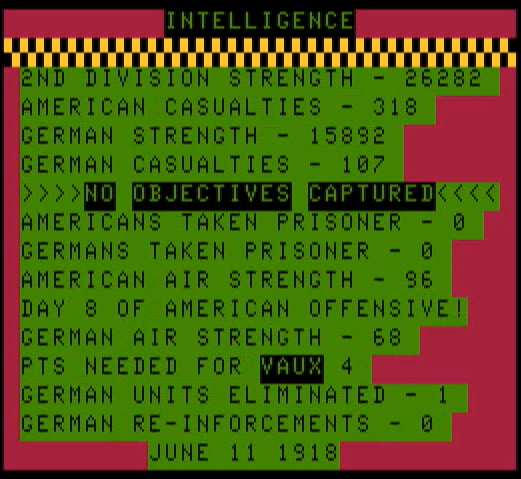

Another obvious borrow from Waterloo is that the map can only scroll up (when there are no units left at the bottom of the screen), and the player must seize successive objectives to unlock “perks”: first Vaux which somehow reduces German air force and allows the Americans to call their own, and then Château-Thierry to stop the German reinforcement and crush their morale. Speaking of air force, the game sometimes interrupts your turn by sending a wave of German planes strafe at your troops.

The manual advises you to spread your troops on the horizontal axis to mitigate damage, but that’s terrible advice. Sure, you can get unlucky when advancing in column, but on average the same number of units will end up in front of a plane in any given turn. On the other hand, by advancing in column and having troops help each other, one can cross the forest much faster. Even better: units sometimes retaliate with “air defense”, destroying the plane after being attacked and thus protecting the units behind it.

And so I advance in two columns (one on the left to reach Vaux quickly, one on the right because that’s where the artillery starts), and boy is that long. My left column is bogged down by an increasing number of German units, but my right column is absolutely unopposed, and still it takes me 8 turns and 40 minutes before the vanguard emerges from the other side of the forest.

What takes me so long? The game is naturally slow to start with (there is a half-second delay to everything), but it has the nasty idea of redrawing the map after each air attack (there are between 0 and 3 by turn) which takes around 20 seconds, to which you can add up to 10 more seconds during which the game searches which of your units can still move. Even worse, your units sometimes disappear from the map, and when they do they can’t help other units cross difficult terrain, so to make them reappear you have to refresh the screen by calling the intelligence menu – triggering again the 20-30 seconds needed to redraw the map and find the unit to move.

If at least there was something at stake during those air attacks – but no. The Germans managed to strafe my right column once and my left column three times, and my total casualties (including ground combat with the Germans) is less than 2% of my force! As for the rest of the German arsenal: gas, artillery and counter-attacks, instead of logically making them “interrupts” like the air attack, the Germans only use them if you wait too long before moving a unit – and I never let that happen.

One hour into the game, my left column is still blocked by a significant German force, so my plan is to move the Marines that are on the right of the map toward Vaux. Unfortunately, they’re blocked by German units all around them:

Combats in Feuer & Gasse are – again – similar to those in early Ark Royal games: you move your units on the enemy square, inflict same damage and return where you came from (or are pushed back far away if you lose the battle). Unlike the Ark Royal games however, units in Feuer & Gasse can be incredibly sturdy: German units can have anywhere between 100 and 900 strength points, and you typically drain them by 10 strength points if you win, occasionally up to 20, more often less. Machine-guns don’t help a lot: they have a random number of attacks (1 to 9 I think) on tiles at a distance of 0-4 in whichever direction you choose, so it can be a long animation to inflict maybe 5-10 damage per hit. And yes, machine-guns sometimes hit themselves, but there is no friendly fire so it’s just a missed shot. As for artillery, they behave the same way but with a longer range, so they hit even less – but at least when they do they inflict significant damage (30-50?). All in all, it’s so incredibly tedious.

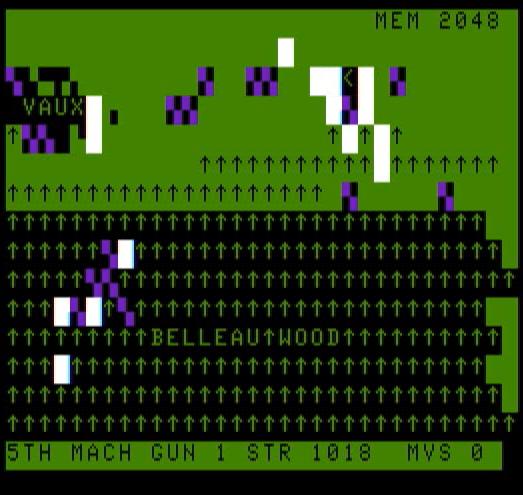

1 hour and half into the game (turn 14) and after realizing that the Germans are never attacking, I decide to let the machine guns and artillery with the infantry and have my Marines bypass the German units. Meanwhile, a few of my units from the left manged to finally break-through and also approach:

Two hours into the game (turn 16), I finally capture Vaux, almost by accident. I had understood that I needed 4 units on the “V” of Vaux to capture it, and so after reaching it with infantry from my left column I waited for the Marines. While doing random moves (because once you’ve done a movement with a unit, the game wants you to exhaust its movement points one way or another, you can’t leave the unit where it is!), I passed over the “V” of Vaux two more times.. and that’s a capture. What I really needed was to enter the “V” square 4 times, even by going back & forth with one unit! If I had known, I would have sneaked a unit long ago!

The capture of Vaux immediately teleports all German units North of the Belleau Wood, presumably to let the map scroll further up. My advance North resumes, interrupted as always by enemy air attacks. I can launch air attacks myself, but they’re just too long and inefficient to bother.

Fast forward one hour later, the map has scrolled up a bit but the game is as dreadful as ever. As I step away for a minute to answer some silly but nonetheless charming question from one of my daughters, I give the computer an opportunity to interrupt, triggering a “counter-attack”: all German units in contact with one of my units attack each and everyone of those units. That’s not the first time that it happened, but I don’t like when it happens because it’s long and it can push back your units several tiles. Well, this time it’s different because one of the German units surrendered.

In truth, the manual states that German units can surrender if surrounded after a failed counter-attack, but I had never managed to trigger such an event before despite intense surrounding, so I had imagined I needed to take Château-Thierry first. Well, maybe not.

I make a bold choice: I’ll let the game run by itself so the Germans can pull as many attacks as they want to, and return to see the results. And so my next master move is to go fold and clear away the laundry.

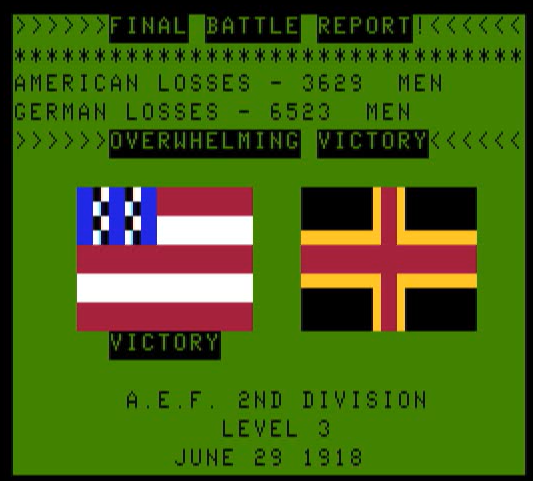

When I returned to my computer half an hour later, the computer welcomed me with the Victory Screen:

A quick glance at the video that recorded while I was away showed that my soldiers went through Hell and back while I was away from keyboard: artillery, poison gas attack and of course wave upon wave of Germans, until the latter passed a threshold where they had received too many casualties to continue.

I return to the manual for the conclusion of our story: “By July 10, Vaux and Château Thierry were in American hands. Von Boehn’s army was in retreat, and the stage was set for the Allied drive which culminated in the Armistice on November 11, 1918.”

America saved the day once again.

Ratings & Review

Feuer & Gasse by Edward Hetzler, published by Picosoft, USA

First release: March 1985 on Color Computer

Genre: Combined Arms Tactics

Average duration of a scenario: 3- 6 hours if you play straight

Total time played : 3 hours, + half an hour folding laundry, which was a more interesting activity,

Complexity: Low (1/5)

Bald eagles Rating: 🦅🦅

Final Rating: Totally obsolete

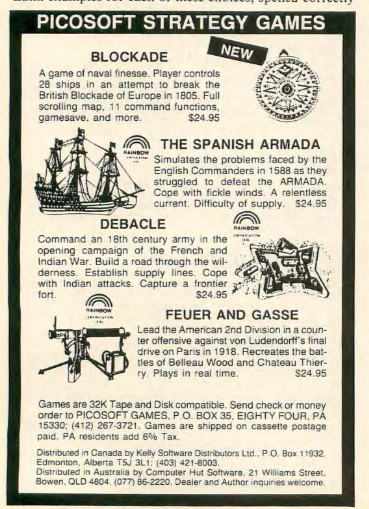

Context – This one is going to be quick: I couldn’t find anything on Edward Hetzler, and almost nothing on Picosoft. Its first appearance is when it started advertising The Spanish Armada in the December 1984 issue of Rainbow. Feuer & Gasse and another game called Debacle were added to the monthly ad in March 1985, and finally Blockade completed the set in November 1985. The last Picosoft ad was run in January 1986, and then it disappeared from digital history. All the games were Color Computer exclusives, all of them besides Feuer & Gasse are lost media and all of them were sold at $24.95

Traits – “Due to memory limitations and in the interest of playability, some dramatic license has been taken. However, the problems you will face are the same as the 2nd Division commanders faced, and the battle(s) which develop during the game will be very similar to actual events.“

Did I make interesting decisions? No, all I did was optimization.

Final rating: Totally obsolete.

Ranking at the time of review: 179/181 This is a horrible copy of an already bad Ark Royal game that fails both on design and on basic quality. It’s terribly slow, it’s riddled with bugs, the balancing is off and there is no joy to be derived from it. I had to go back and read my reviews of Raiders’ 41 and Battle of Gettysburg to rank Feuer & Gasse, and the latter manages not to be the worst game thanks to gameplay that, as buggy as it is, makes a modicum of sense (unlike the one in Battle of Gettysburg) and by making your actions a minimum relevant to your performance (unlike Raiders’ 41). Still, a superb entry to my Wall of Shame.

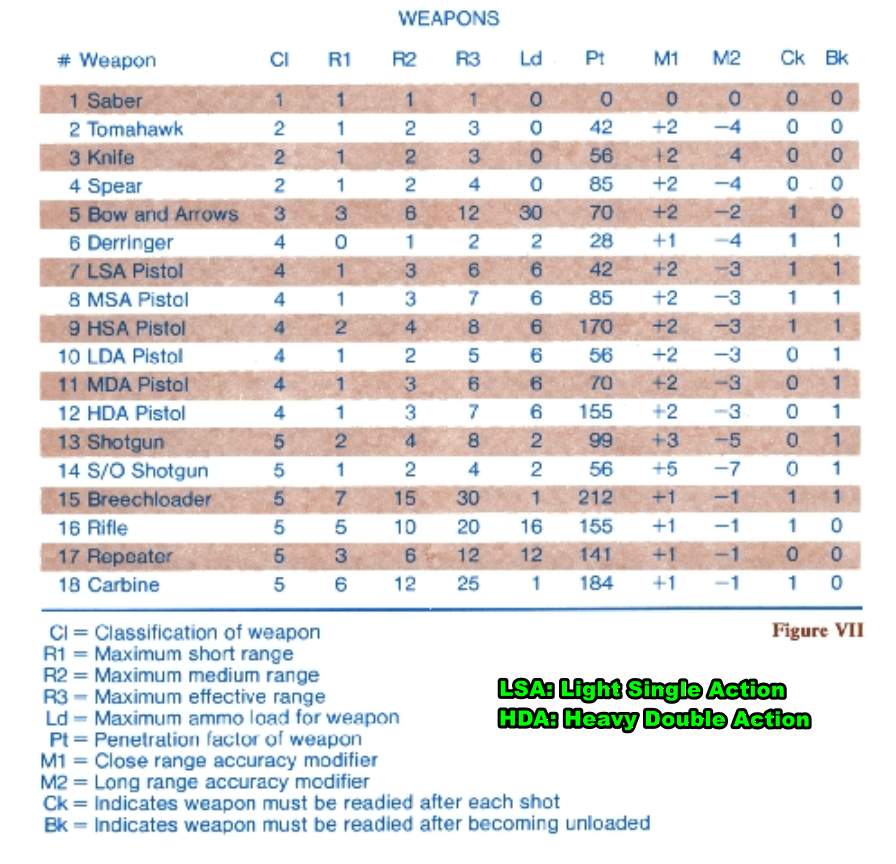

My palate has been properly cleansed – maybe a bit too much – and the vagaries of releases means that I have 3 different SSI games next, including Six-Gun Shootout. Just like Field of Fire. Six-Gun Shootout allows you to edit the names of characters. If you want to die in a ditch, drop your name, and tell me what weapons you would prefer your pardners to pry from your cold, dead hands.