After covering five battles in Field of Fire, including the disastrous battle of Balleroy, I feel it is time to conclude on the game. But first, as I finished the campaign, here is a short account of the three remaining scenarios:

Scenario 6: For Aachen

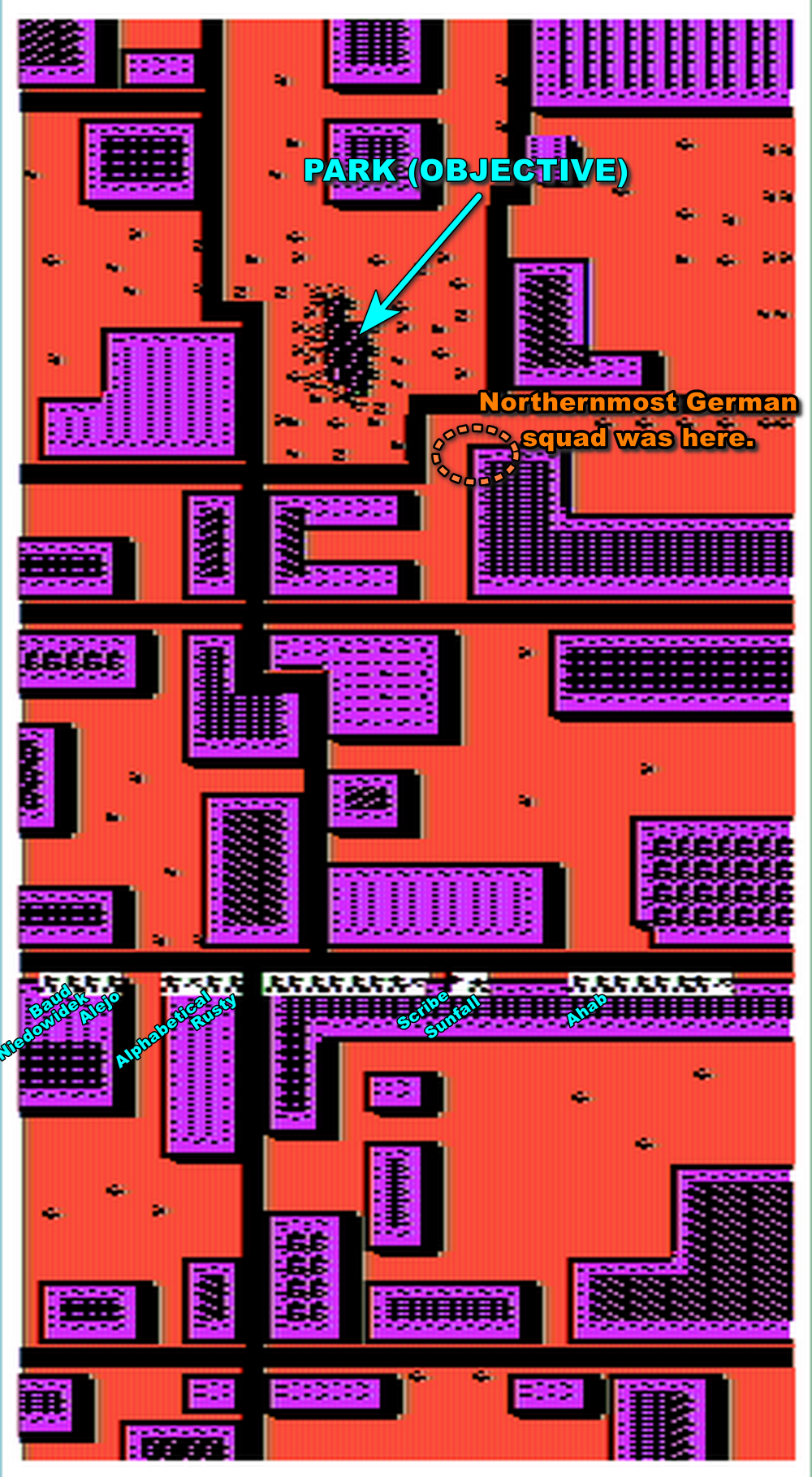

This was probably the least interesting scenario of the campaign. The map is narrow (one screen wide instead of the usual one-and-a-half screen) and neither the bottom third nor the top third are used. The objective is to reach the park with as many troops as possible.

With 24 squads of infantry, MG or bazooka (+ the HQ squad and a squad of spotters), I advance my soldiers in a line and concentrate fire on anyone speaking German. I lose one anonymous squad in an assault and a few men here and there, and otherwise clear the map in 35 minutes out of 60 allocated. Frustratingly, killing the last German unit (South-East of the park) immediately ends the battle. I did not have the opportunity to occupy the park, and so all I received for my effort is a minor victory. I lost 29 men, around the same as in the first scenario – not bad given I was not facing half-asleep Italians this time.

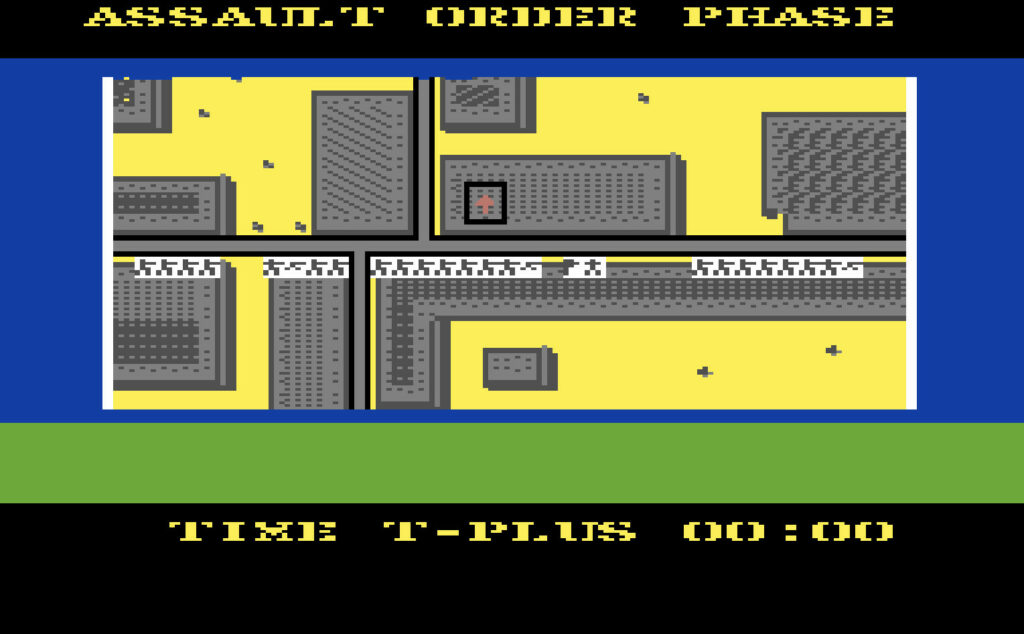

Scenario 7: Ardennes Dawn

I did not love this scenario either. The objective is to prevent the Germans from seizing the town. There seem to be two viable strategies:

- strategy #1: Regroup in the town and ambuth the tanks there with guns and infantry in assault mode,

- strategy #2: Defend in front of the town with the infantry serving as meatshields.

Unfortunately, I was naive and followed the recommendation of the manual: “[we suggest] leaving the bazookas, MGs and ATGs in the forward cover along with the tanks to dull the initial advance”, so I left most of my infantry in the town where they played cards for the entire battle.

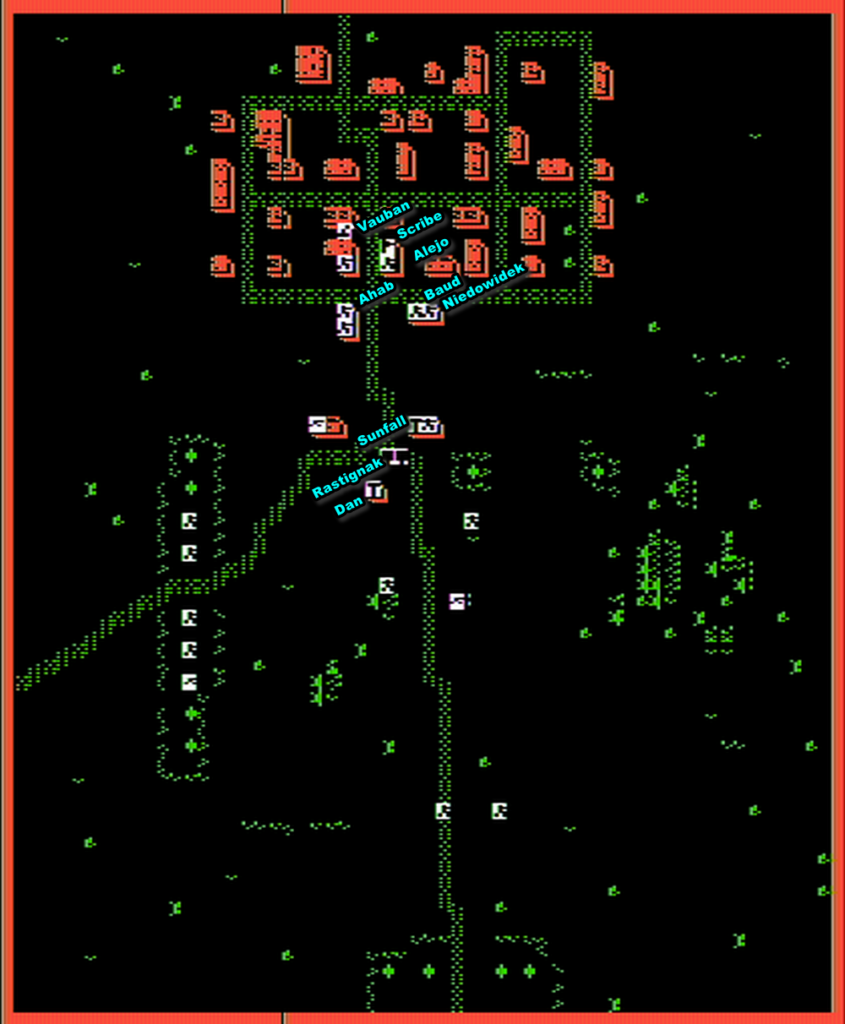

Meanwhile, two tanks (including Rastignak’s), two anti-tank guns (the only scenario in which the Americans have some, in this case manned by Sunfall and Dan), two bazooka teams and a handful of infantry I did not put in the town had to stop the German advance. If I had known how many Panzers would be coming, I would have chosen another plan.

The limitations of the game make this scenario irritating. The Germans don’t wait for you to “interrupt” before moving, but they also move when you do interrupt, which of course you must do after they move to reassign your targets (at least you do the assignment after the German second move, so you’re not stuck in a loop). The battle did not go well: it’s the morning, so as the battle progresses, visibility increases. By the second half of the battle, there were a lot of German tanks shooting at me, and I did not have enough meatshields for my anti-tank units to avoid being pinned or worse suppressed. By the end of the battle, I had lost Dan and at least five anonymous squads and the Germans lost maybe 2/3 of their tanks and a few infantry squads on top. The game called it a minor victory, and this time I concur.

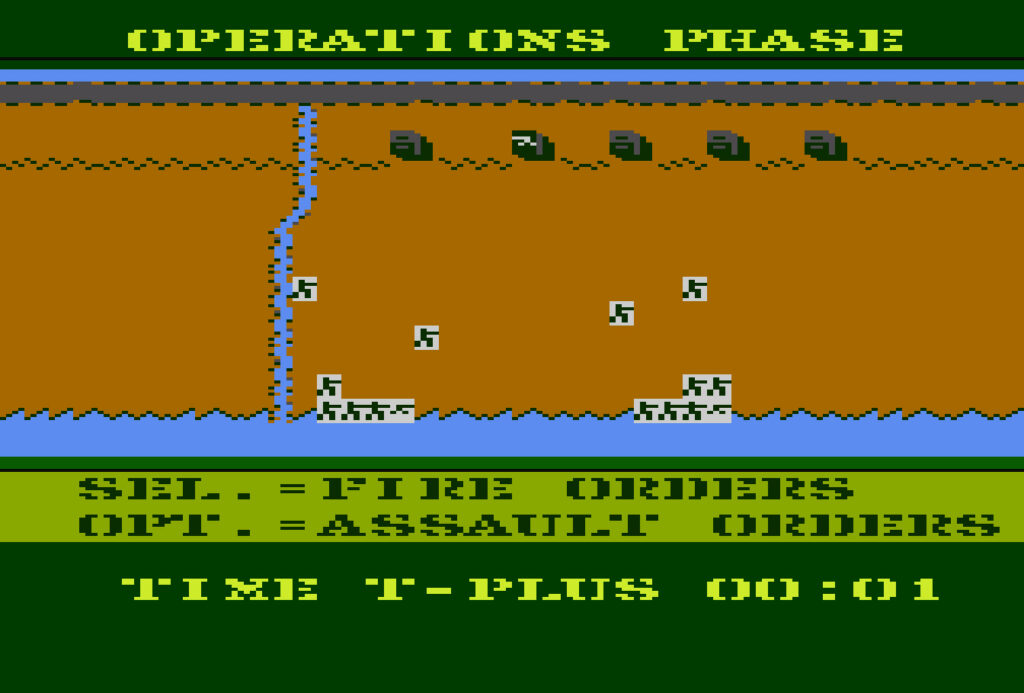

Scenario 8: Roer’s Crossing

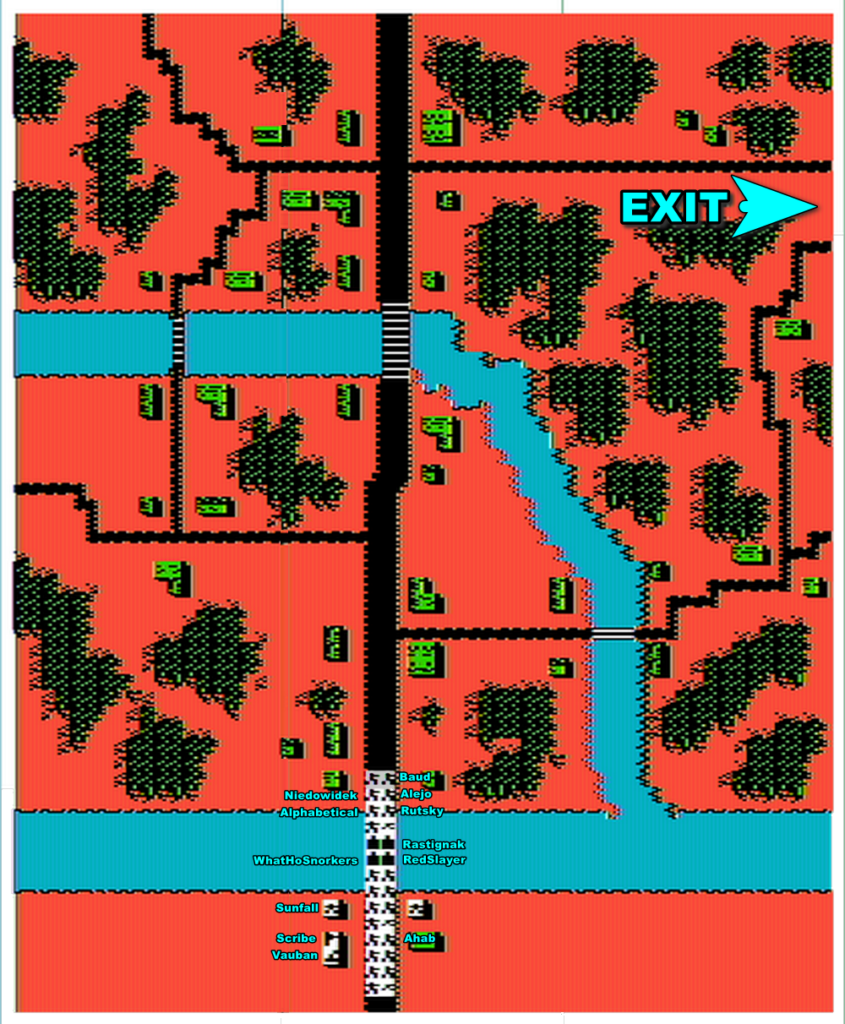

The last mission is the crossing of the Roer, and the objective is to exit all my units through the Northeastern road. This is one of the best scenarios of the campaign, and certainly the most ambitious; too bad it’s let down by the game’s UI. First, there are quite simply too many units to move. Second: given the range at which I am engaged, I need to frantically pan the view during the resolution phase to spot those few frames during which hidden Germans appear when they shoot me.

The first town is fiercely defended by the nazis: infantry, machine-guns, panzershrecks and two AT guns near the Northern bridge that shred my infantry. Baud and Niedowidek find their demise, Alejo barely survives.

After clearing the village, I have a surprise:

Well, it’s not a total surprise because the manual warned me about it, so I only lost one infantry squad, and then another because the bridge on the left is also trapped. This leaves the narrow Eastern bridge, which takes ages to cross. Units are not smart enough to take the bridge if you order them to move on the other side of the river, so you have to first ask them to move in front of the bridge, then ask them to cross and finally move them where you need them. Worse: putting them in a conga line in front of the bridge to cross quickly does not work, because even if it plays in real-time, the game’s engine moves the units in a set order, so if a unit behind another tries to move first, it will move diagonally and miss the bridge.

The rest of the map is less ferociously defended than the village, but while most of my units are stuck in the traffic jam before the bridge, those units that managed to cross don’t have critical mass, and so I lose my last squad of the campaign in an assault against an AT gun. After destroying that gun and tackling a couple of extra German squads, the road is clear to the objective and all my units have left the map by the end of the allotted time, granting me a major vict… oh no! at the last second it got converted to medium victory for no reason at all.

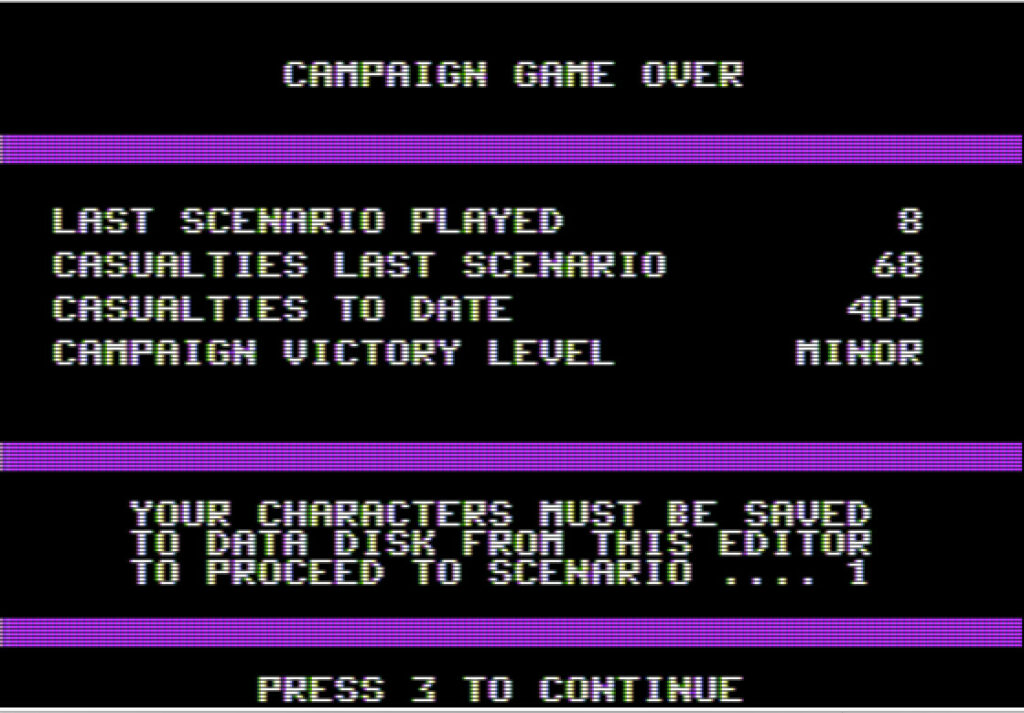

It’s the end of the campaign, and my victory level is only “minor”. I don’t think the scenarios were always fair with these, but on the other hand with 405 casualties, compared to 32 squads of 6 men, I had more than 200% casualty rate so maybe I should not be too proud. As for our daring commenters, only 10 out of 22 contributors (including me) reached the end of the campaign.

Ratings & Reviews

Field of Fire by Roger Damon, published by SSI, USA

AARs: North Africa, Sicily, Omaha Beach, Sainte-Anne, Balleroy

First release: October 1984 on Atari

Genre: Small Scale Tactics

Average duration of a battle: 1-2 hours

Total time played: Around 12 hours

Complexity: Low (1/5)

Final Rating: ☆☆☆

Context – Based on my research and the testimonies I could collect, I came to the conclusion that Field of Fire‘s designer Roger Damon was a ghost. Damon had published his first game Operation Whirlwind at Brøderbund, but when I queried Brøderbund’s founder Doug Carlston about him, he answered: “I don’t remember meeting Roger Damon, and I met most of our developers“. For his second game Field of Fire, presumably disappointed by the sales of Operation Whirlwind, Damon contacted SSI, but when I asked SSI’s founder Joel Billings about him, he answered: “I have absolutely no memory of Roger, which is surprising as I usually have some recollection of our various developers. […] It’s strange that he did so many games with us but I have no recollection of him.” I could not find any biographical details, beyond a list of games, that I can safely attribute to “my” Roger Damon in archive.org. I did find a Roger Damon in a 19th century document called “History of Cuyahoga County“, and I choose to believe that’s our guy.

Whatever the circumstances, Field of Fire did not arrive fully baked at SSI. Billings again: “When [we received] Field of Fire, we decided to turn it into a series of battles fought by the 1st Division in WWII. I don’t remember how much of this came from him, and how much came from us, but clearly, I had a personal interest in the 1st Division story and could get some info from my uncle to help.” Billings’ father Robert and paternal uncle Linwood were both decorated WW2 combat veterans; Linwood in particular had started in North Africa, landed in Normandy and continued his career long enough to be on the receiving end of the Tết Offensive. Not all battles were based on Linwood’s direct experience, but some were, starting with the Battle of Sainte-Anne for which he wrote an After Action Report that was then copied in Field of Fire‘s manual.

Field of Fire was initially released on Atari in October 1984 – an unusual choice for SSI but it was Damon’s platform for Operation Whirlwind. The game was later ported to Commodore 64 in July 1985 and finally to Apple II in April 1986 – at this point whatever innovation Field of Fire had brought was old news.

Field of Fire was sold for $39.95, which corresponds to SSI’s “cheap” price point. It could only be played in solitaire.

Traits – Field of Fire innovated in more ways than one, justifying the time I spent on the title. The most obvious is the “real-time with pause“, a feature which I previously only encountered in Carriers at War. While relatively seamless when playing, this is not a true real-time yet; under the hood the game still alternates between movement phase and fire phase, which means that when you interrupt the action the game has to finish resolving the turn. Worse, as I explained and with the exception of forced retreats, the computer still moves in turn-based mode, leapfrogging its units during interruptions (triggered either by design or by the player). Unfortunately, most scenarios include enemy counterattacks (or simply “attacks” in one case), so the player must time his pauses to exploit the engine’s idiosyncrasies. It takes away from the immersion and makes the game feel more transitional than really innovative.

Compounding the issue, the game design is not properly adapted to the specificities of real-time (in pause or not). Given the scale of the game and the choice to sacrifice 1/3 of the screen to fit the top and bottom text banners, you can’t have all the action on one screen, so stuff happens that you are not aware of. You can try to keep track, but then you must slowly pan the map with the cursor, which moves slowly across the screen. To an extent, Field of Fire suffers from the state of technology and of art design at its time: no mouse, no mini-map, no seamless zoom in & zoom out, archaic sound feedback. Still, game design should have adapted to those constraints: shorter maximal range compared to the size of a screen (AT guns’ range when on an elevated position is half the map!), fewer units to babysit, units immediately revealed after firing, ideally with a text notification on top. When I played my first battle, I compared favourably Field of Fire‘s real-time with pause to Carriers at War‘s; after more than 10 hours of playing the former, I have to reassess my judgement.

The second main innovation is the campaign mode. So far, only two games offered some sort of campaign mode where your characters would improve between battles: Galactic Gladiators and Eagles. Still, their campaign modes were janky: Galactic Gladiators forced you to create all your scenarios, and Eagles forced you to “store” your character outside of the game and re-input his stats every time you started a battle. For the first time in a game, Field of Fire stores your characters and lets you keep them in a set of pre-designed scenarios. However, here again, the game does not implement that logic fully. The manual states that units gain experience if they survive battles, but Field of Fire does not show anywhere the experience level of your units (I tracked it on the side); and playing the game I never felt any difference between rookies and veterans either. Field of Fire‘s campaign system plays like a blueprint for future games to expand upon, not the final form of an ideal “campaign” feature.

Beyond those two key features, I am pleased by the diversity of the situations I faced in the various scenarios: surprise attacks, night combat, tank battles, urban warfare, against-the-clock progression and even, for the first time in wargaming history, hardcoded events like bridges blowing up. I also liked the large unit diversity both on the American and on the Axis side. I am however less happy, again, with the UX side of things, in particular the lack of feedback on unit status. It is impossible to know at a glance which unit is under attack, which unit is in a good position to hit the enemy and which unit is not, and what’s the condition of the enemy.

This brings me to the last major issue with the game: except in a few missions, there are just too many units on the map, which would be manageable if your soldiers didn’t require careful babysitting. I already explained the issues with movement in narrow spaces, but that’s only a small part of the issue with controls. For instance, your units will never open fire on their own, and will only attack squares, not enemies, which means that every time an enemy moves (including the relatively common one-square retreat by enemy units under attack), you need to update the order of all yours units, lest they continue attacking an empty square. Worse: by an unexplainable oversight, you can’t give orders to units that are pinned or suppressed – for instance the order to stop advancing; your only solution is to cancel movement for all your units and then renew the orders of everyone except the pinned/suppressed unit. Maddening!

I’d like to finish this section with a positive note. I deep-dived into Field of Fire‘s many flaws, but that’s because I had huge expectations after the first battle. Its many strengths should be obvious from my AARs, and they make its shortcomings more salient than in a game where no feature stands out compared ot its peers.

Did I make interesting decisions? Yes, plenty of them – though too much time was spent actually conveying the decision to the little pixel soldiers.

Final rating: ☆☆☆ Field of Fire is a great game for 1984, but issues with controls and visual feedback prevent it from being a seamless experience. Eventually, the issues add up and prevent Field of Fire from reaching the top of my leaderboard.

Ranking at the time of review: 4/165

Reception

Field of Fire is one of those titles that received so many reviews in all languages that it would be pointless to list them all. With one key exception, the reviews ranged from “quite good” (Compute!, December 1985) to “simply superb” (Zzap!, April 1986), the average being around “excellent“. Family Computing even put it in its January 1985 list of “Greatest Games of 1985“.

Two remarks stand out in many reviews: the fact that the game is for beginners and experts alike, and the personalisation of the soldiers. As Patrick Kelley explains it in Analog Computer (March 1985): “[SSI] added one of the little features that makes FF a winner. Each one — and I mean each one — of your pieces has a name and a brief history attached, making it that much harder to see him get taken out.” The reviewers also praised the attention to detail and the tactical flexibility offered by the game. Complaints about the game were rare, with James Trunzo writing for Compute! mentioning a few I agree with: “Compared to the Germans in most scenarios, your men are just too good. Close assaults […] almost always result in a victory. Also, games sometimes seem to end abruptly.”

Computer Gaming World never directly reviewed Field of Fire, but in May 1987 Jay Selover compared the three “WWII Tactical Infantry Systems” on the market: the venerable Computer Ambush, Field of Fire and Avalon Hill’s Under Fire (1985). Selover finds strengths and weaknesses to each of the games; for Field of Fire, he cites “ease of play” and “campaign mode” among the strengths, but criticises the documentation, the “indistinguishable” units and the “lack of scenario variant and two-player option“. He does not say it in all words, but clearly he ranks Field of Fire above Computer Ambush and below Under Fire.

I mentioned one key exception, and that’s none other than Evan Brooks. Brooks first mentioned the game in Current Notes (November 1985), where he rated the game 2 stars and half: “Scenarios are varied and enjoyable; however, this reviewer is not overly enthused about the historical accuracy and lessons learned from this simulation. Nevertheless, it is a good introduction to computer wargaming“. He would repeat this statement after moving to Computer Gaming World, though Field of Fire will manage to keep its two stars until at least 1993.

Field of Fire sold 10 700 copies in the United States, making it a success relative to the typical SSI wargame. Roger Damon will continue working with SSI, with a Panzer Grenadier in 1985, a spiritual sequel to Field of Fire but in which you play, well, Panzer Grenadiers, and finally the massively successful Wargame Construction Set in October 1986. I may play both of these games on this blog!