As always, the rating and review posts assume you have read the After Action Reports : Advanced, Expert

Easter Front 1941 by Chris Crawford, published by APX and later Atari, USA

First release : August 1981 on Atari

Tested on : Atari emulator

Total Hours Tested : 10 hours

Average duration of a campaign: 3 hours

Difficulty: Easy (to play) (1/5)

Would recommend to a modern player : Yes

Would recommend to a designer : Yes

Final Rating: Still interesting

It is difficult to review Eastern Front 1941. The game was enormously influential, comparable to the later influence of Dune II or Warcraft on RTS. I wish the Digital Antiquarian had covered Eastern Front and the early years of Chris Crawford, as he did for Doug Carlson or Joel Billings, but he did not and I am on my own. The following mostly comes from Chris Crawford’s book “On game design” – published 30 years after the events – as well as his earlier “The Art of Computer Design” and several interviews he did here and there. I had a short email exchange with him, but nothing related to the history of Eastern Front 1941 directly.

Ultimately, Eastern Front 1941 came to life because Crawford had a vision of the computer game industry that no one else shared. In August 1980, Crawford – already working at Atari – was shown by his colleague Ed Rothberg a module (scrl19.asm) making it possible to scroll smoothly. Immediately, “[Crawford] realized that this opened up a world of possibilities for wargames. No longer would we need to squeeze the entire map onto a single 320×192 screen; now we could have huge maps“. Indeed, all existing wargames up to that era either fully occurred in a small battlefield (Computer Conflict, Invasion Orion, Operation Apocalypse, or all the early Avalon Hill games) or featured a larger battlefield which could only be navigated through complex commands (Computer Ambush, the Shattered Alliance), a situation sometimes poorly mitigated by an option to use different levels of zoom (Torpedo Fire, the Warp Factor). Unfortunately, Crawford’s roadshow trying to convince developers to transition to Atari to leverage the possibilities offered by such technical prowess was unsuccessful – Apple II was too established as the “serious” home computer for wargamers.

Disappointed, Crawford decided to develop his own wargame to drive home his point.

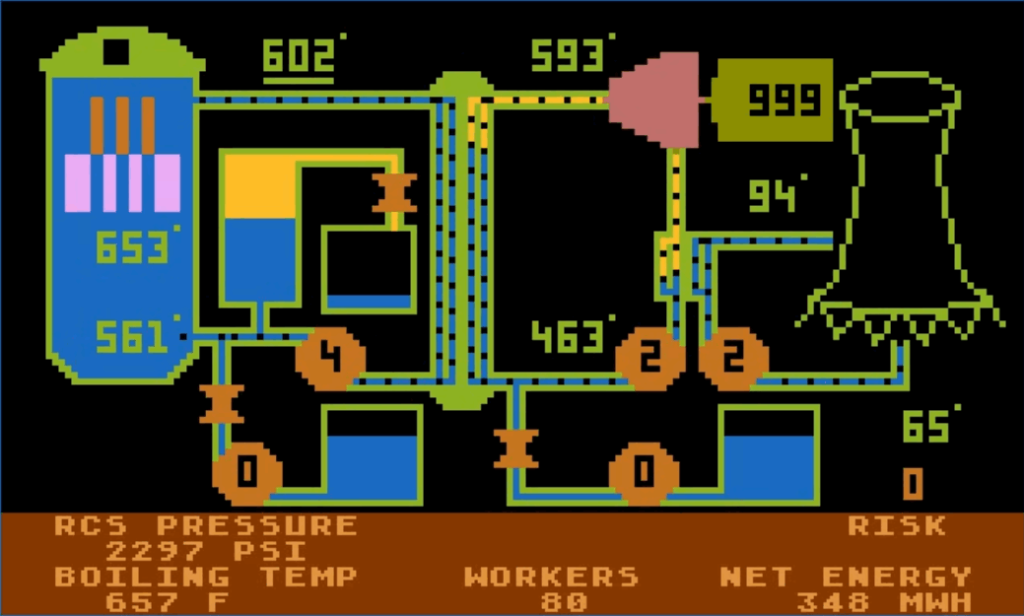

Crawford was not new to the genre : he had developed Tanktics of course, but also the confidential (and lost) first iteration of Legionnaire in 1979. More generally, he was already something of a veteran in an industry that had just started blossoming, with two more released games to his credit : Energy Czar and the famous Scram, a “nuclear power plant simulation”. He had worked on another wargame covering the entirety of the Eastern Front (1941-1945) as a personal project : “Ourrah Pobieda” (Hurrah for the Motherland) but, unsatisfied by the resulting game “dull, confusing and slow“, he had shelved the project in 1979. In December 1980, Crawford pulled the project out of the shelf.

The alpha version of Eastern Front 1941 looked like little more than a WW2 theme, the two-stats system of both the 1979 Legionnaire and Ourrah Pobieda (combat strength as a ratio of a maximum muster strength) and the scrolling map for which Crawford claims no credit. But Crawford wanted more, and more specifically he wanted to solve two issues he saw as plaguing early computer wargames : poor UI and terrible AI. For the former problem, the scrolling technology almost spelled the solution for him : the game should be fully controllable with the one-button Atari joystick. It is only regretfully and forced by his design that Crawford added two other non-joystick controls : cancel movement and next turn.

As for the AI, Crawford claims that it is where he deployed the most significant effort and what he was the most proud of. He made a decisive choice : the AI would think “bottom-up”, as if divisional commanders tried to coordinate their actions, rather than “top-down” as a commander-in-chief overseeing the global situation. This allowed the AI to be iterative : initially each AI division thought about what was its best move given the enemy position, then in another iteration what was best for itself given enemy position and the movement of the other allied divisions, then the following iteration would take the result of this second iteration into account, and so on and so forth. The AI “thought” during the player’s turn, and this iterative process allowed the AI to think more as the player took more time to play. As an added bonus, it created organic and realistic movement of the Soviet armies, as the AI units push together or retreat together, and converge toward a frontline.

Even after having improved AI and control, Crawford was still not satisfied with the game. It was unwieldy : there were too many units around, it was too long to play, and the AI did not cope as well as expected. Eventually, he made two defining changes : he reduced the game’s scope to the first year of the war and introduced zones of control (straight from tabletop wargaming, though Computer Napoleonics did it first on computer). This allowed him to deflate the number of units, culled the playing time tremendously and helped the AI. With the final addition of logistics/supply and some rounds of polishing, there was a game, a very good game- an exceptional game even, but then there was the question of how to distribute it.

It should have been obvious – Crawford was after all an employee of Atari – but Atari was convinced a wargame would never sell. There was a solution : the Atari Program Exchange, and so Crawford published his game through the third-party publishing channel. As Crawford says in On Game Design :” Other people can’t see your vision; you have to make it happen yourself.“

On the APX store, Eastern Front 1941 became an immense success, that would spawn a number of reeditions, additional content and other ancillary releases. I can count :

- The initial APX version (1981). There have been at least four versions of the manual but I am not sure whether there was any modification to the code itself.

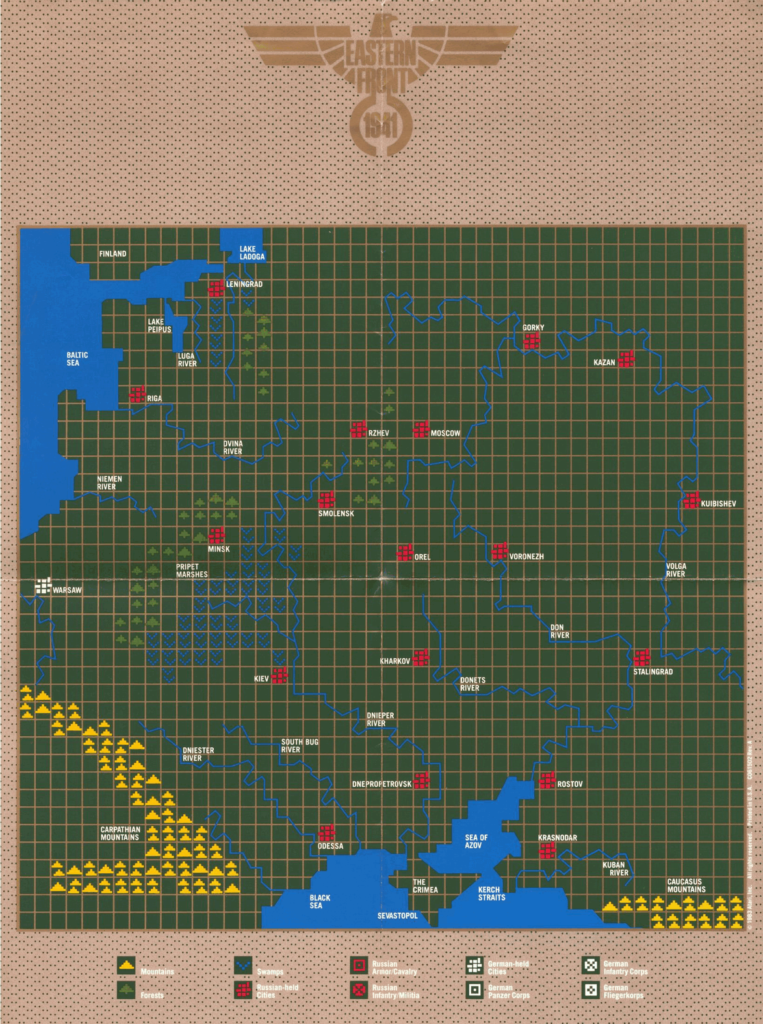

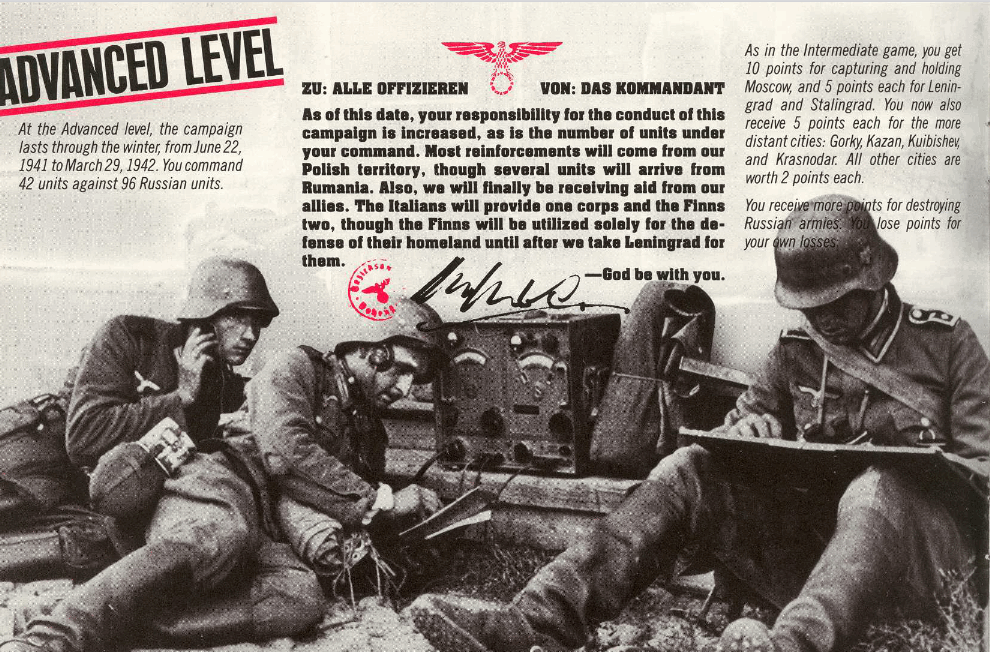

- The Atari version (1982). It introduced different levels of difficulty, and in the expert mode the German air force, unit postures and a different balancing as I have showed in my AAR. It also included more quality of life stuff : save/load feature, cities directly named on the map changing color depending on who controls them and improved animation in turn resolution. Finally, it was sold as a product mirroring SSI in production value : excellent manual and high quality map included.

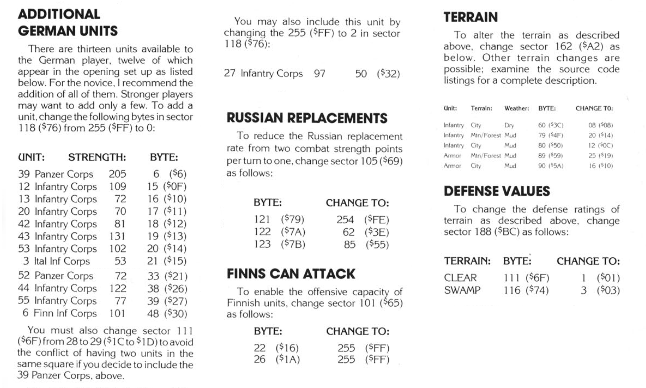

- A scenario editor (1983), sold under APX, fairly limited in scope (eg you cannot change the map, add nationalities for units or even freely change how much points cities are worth). One could make I believe a decent WWI scenario, if they accepted to call the Austro-Hungarian units “Hungarians”, but there is no way to create for instance a smaller scope scenario.

- A scenario disk (1983) by some Ted Farmer, also sold under APX, which introduced 1943, 1944 and 1945 scenarios of increasing difficulty. I do not believe it is possible to win the 1945 scenario. Crawford had no knowledge of these scenarios until my exchanges with him to prepare this post.

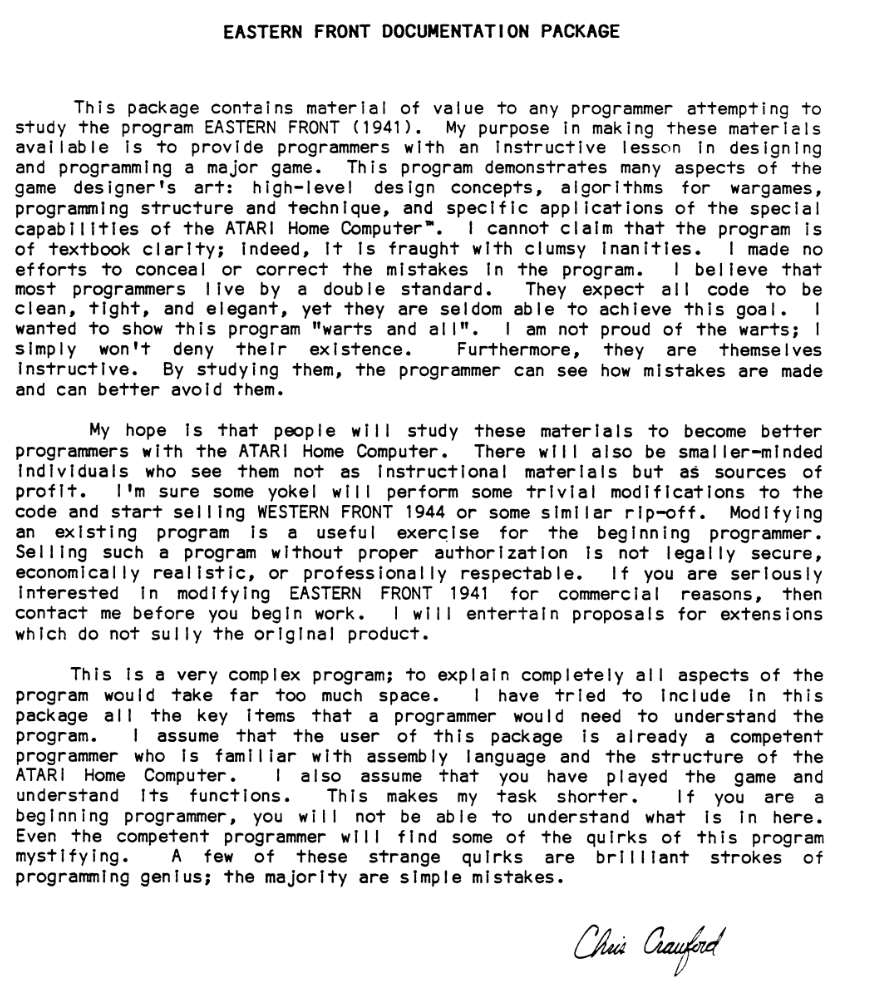

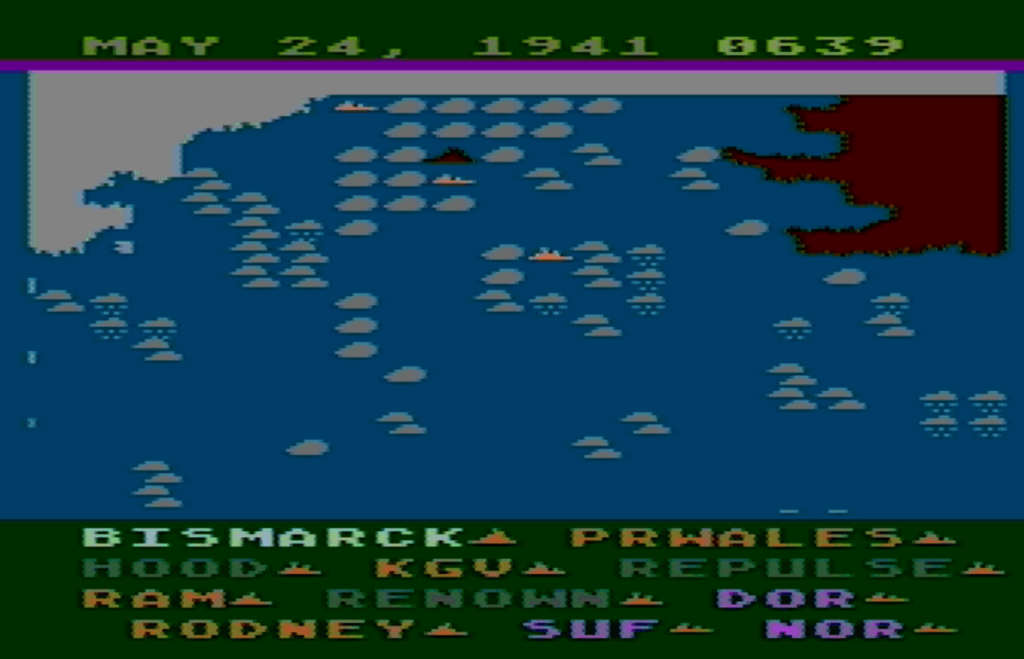

- Finally, Chris Crawford did the unthinkable and sold the Assembler source code of the 1981 APX version of the game directly in APX. It was the most expensive item of the catalog : $150. It sold plenty, though according to Crawford only two games would be based on that code : Crawford told me that one (unpublished) is a Battleship Bismarck-themed game by Kellyn Beeck of Defender of the Crown fame, the second one Crawford could not remember but I believe it is Saratoga by Paul Wehner. The source code includes detailed explanations on how the game was designed and coded, so even for a non-coder like me it is interesting literature.

Chris Crawford himself would work on a Western Front game, though it was never completed.

This has been my longest intro so far, so let’s move to the rating & review itself.

A. Immersion

The first thing to say about Eastern Front 1941 it that it is immersive. This is the first game I’ve covered, with the possible exception of Computer Bismarck, where I really felt I was standing in the shoes of the commanders. The graphics of the game are simple, but even today they don’t look primitive – they are functional. The game has the right amount of historical fluff (name for units, Hungarian & Romanian units) to feel realistic. The player is never pulled out of the simulation by weird display issues or unpractical UI.

The Atari version pushed that further. The graphics during turn resolution were improved significantly, with “attack arrows” and smooth movement :

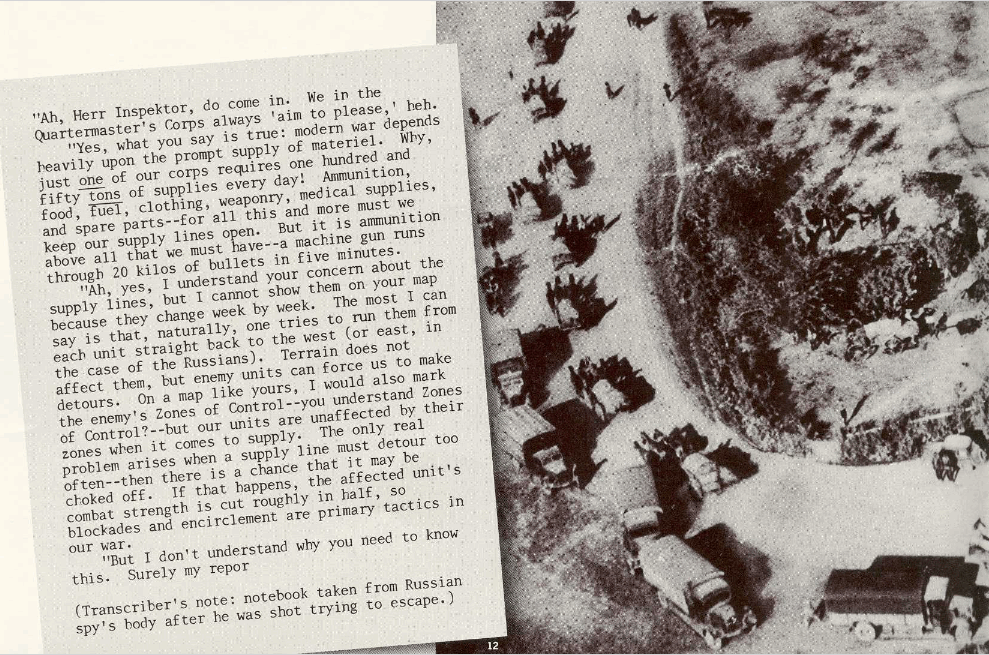

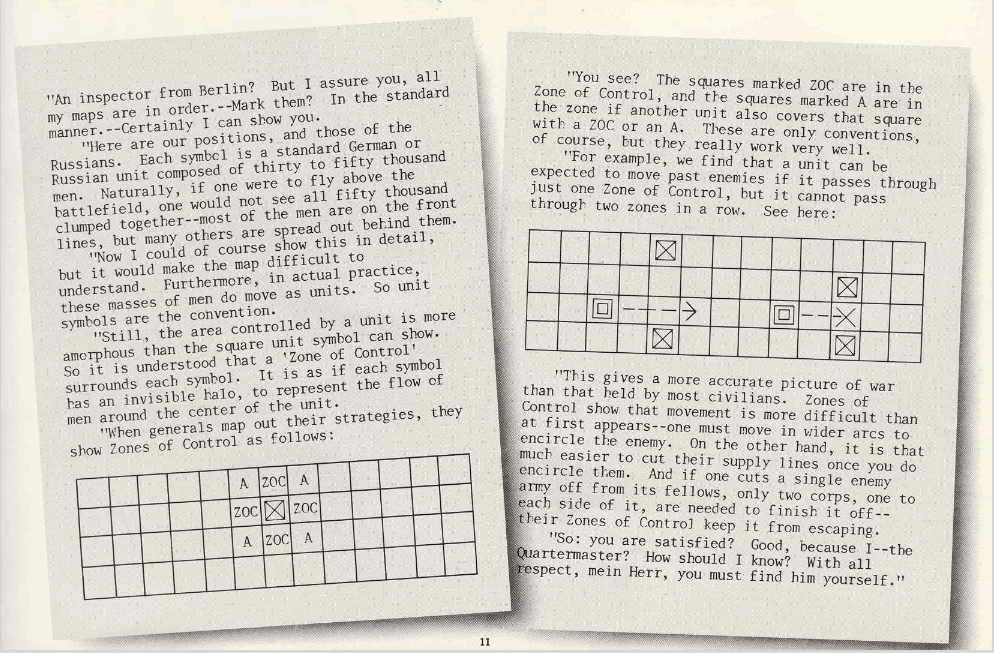

But where the game really stands out (for the 1982 Atari edition) is on the manual. Except from the very basic (“how to move an unit”), features are introduced as the level of difficulty increase, through contextual texts in the manual that also happen to also describe the historical situation. Here is for instance how supply is introduced in the “intermediate” level :

The manual concludes by a history of Operation Barbarossa. Interestingly, the editor manual ends with an essay with pacifist undertones written by Crawford called “the lot of the common soldier”, describing fighting but also living conditions on the Eastern Front.

Rating : Good

B. UI , Clarity of rules and outcomes

Two words : smooth scrolling. After more than 20 games without it, it is very welcome, it feels like changing era.

One of Chris Crawford’s objectives was to create a wargame that could be played by anyone (as for winning it, that’s another topic). And indeed, the game is deceptively simple to play. To move an unit, just hold the button on a unit, then drag. You can even plot several turns in advance this way :

I believe it is the first game to make use of “drag & drop”, though I could be wrong.

The addition of stances did not impact the philosophy : the first tap on a unit is the movement order, but if you want to enter stance mode, release then tap again. Once in stance mode, moving the joystick in any of the four directions will change your stance.

Not only is the game simple to play, it is also one of the few wargames where you don’t need a reference card nor a good memory to play. This comes from Crawford’s philosophy of avoiding what he calls “dirt” : special rules, exceptions to the general cases, etc. The only case of dirt that Crawford felt he could not remove was the rule forbidding Finns to attack Leningrad. It was either that, or no Finns, or Leningrad falling way too easily.

Keeping with Crawford’s approach described in Tanktics, the exact mechanics and calculations of the game were not fully explained (at least until he released the source code). But the game and the visuals are intuitive enough that everything feels natural that you just grasp it after a few turns.

My only reproach as modern gamer is a bit unfair, as certainly no game would do it for years – there is no way looking at the map to have a view on the health and supply situation of your units, you need to individually check all of them every turn, especially in winter when supply issues strike semi-randomly.

Last thing I should mention : as I said, in Eastern Front 1941, AI thinks during your turn. This means that there is no time spent waiting for the AI : you prepare your order, resolve your turn, and then it is next turn already. This is something even modern games with simultaneous turns do not do.

Rating : Very good

C. Systems

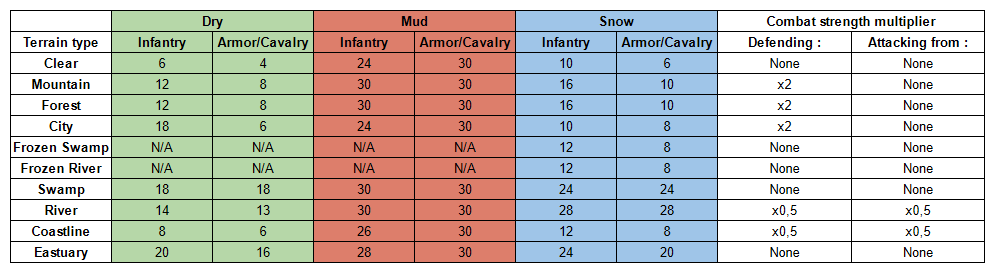

I have described some the game rules in the After Action Report, but here is a more systematic coverage based on reading all the available documentation :

Movement :

- Turns are divided in 32 “ticks” – see them as action points,

- Movement in clear terrain takes 6 ticks for infantry and 4 for cavalry/tanks, more difficult terrain take more,

- Units project zones of control (ZOC) around them. Enemy units can enter a ZOC freely, but they cannot move from ZOC to ZOC.

Combat :

- Units have two stats : Muster Strength and Combat Strength. Muster Strength acts as a maximum to Combat Strength, though it is not a fixed value either,

- German Muster Strength only increases when a nearby German unit is destroyed, which represents surviving troops merging with a neighboring unit

- Soviet Muster Strength can increase in the same circumstances, but any Soviet unit in supply gains 2 Muster Strength every turn.

- Attacking takes one tick, so there can be up to 32 attacks in one turn. Chance to hit is the unit combat strength/256. If a unit is hit, it loses I believe 1 in muster and 3 in combat strength in Expert,

- Units in defense counter-attack with their own combat strength every tick with the following modifiers :

- Multiply the combat strength by two if the unit is entrenched,

- Multiply the combat strength by two if the game is in “Expert”,

- Multiply the combat strength by two in mountain, forest and city,

- Divide the combat strength by two if the unit is moving,

- Divide the combat strength by two if standing on a river or on a coastline,

I believe that those multipliers are the real reason why units ended up depleted in my Expert AAR : entrenched Russians effectively fought four times better than in Advanced.

Sadly, I don’t know the impact of the Assault mode, as the numerical impact is not stated anywhere – the commented source code is from before this mode was added.

- After that, the game checks for retreat, a unit breaks if :

- Its combat strength is below 50% of its muster strength for Germans and Finns

- Its combat strength is below 87% of its muster strength for Russians, Romanians, Hungarians and Italians.

- If the unit breaks, it either moves away from the opponent or, if it cannot, receives additional damage and stays put.

Supply and recovery :

- Units not in combat recover (I believe) 1 strength point every tick, 2 if they are particularly weak compared to their muster strength,

- Supplies are normally traced horizontally to the left (Axis) or right (Russian) side of the map. If the direct route is blocked by units or an enemy ZOC, the computer will try to find a route that does not “twist and turn” more than a fixed limit (lower for the Russians). If it can’t, the unit is out of supply,

- Axis units are also always out of supply during the muddy season,

- Axis units, even if they can trace their route to the left, have a chance to be out of supply in winter depending on how far East they are, from less than 1% (absolute left of the map) to 70% (absolute right of the map).

- Units out of supply lose half their combat strength.

And … that’s all for the ruleset. Very simple and works like clockwork.

The ruleset has two consequences that are not-so-obvious. The first one is that a large part of the player’s attention will be on avoiding traffic jams : several units crossing the same square could be blocked because the front unit cannot move. The second one is that due to how zones of control and pursuit work, if you don’t pay attention you can have a situation where your unit charges forward while the other units are stuck behind.

Consider the case below : the tank corp attacks an enemy, chases it and follows it. The infantry behind the tank corps follows, as ordered. The tank carries on the attack, more pursuit, except this time the zones of control of the Soviet units above and below stop the infantry from following, and the tank is badly isolated.

The first issue is realistic, the second less so ; both are part of the game and can easily be avoided with some planning, but I did not like it, and the second in particular has consequences as you need to slow down your offensives to avoid it.

Obviously, this is marginal. My real problem was with how supplies work. As much as I can appreciate the simplicity of its design, I don’t really love it. I like my supply routes to follow railroads and emanate from cities. Given how important supply is – and how much it can cripple your effort, it is a bit frustrating to have so little control on supply allocation.

Rating : Good

D. Scenario design & balancing

The base game has only one scenario, though already well designed. The Atari version has 3 that I would not consider tutorials (Advanced, Expert 1941, Expert 1942), and then there are 3 more in the expansion disk. With three hours to play one scenario and significant replayability for each one, there is a lot of gaming time – more so than any scenario-driven game I’ve covered so far.

Scenarios are very replayable because the AI is excellent. There are no easy exploits that, once understood, make the game trivial. The AI will try to break from encirclement, aggressively push where you are weak and reconstitute frontlines any time you let it breathe. And as I explained, this excellent AI does not even force you to wait while it prepares its turns.

Rating : Excellent

E. Did I make interesting decisions ?

Yes, many.

In Eastern Front 1941, you will not have troubles pushing back the Soviet initially, as they break much sooner than the Germans, but if you don’t trade very favorably in terms of muster strength you will be depleted before the end of the war. The only way to trade favorably given the advantage in defense is either to cut the supply of the Soviets or to break them in squares from which they cannot retreat (forcing them to take muster strength losses instead) ; and really you need to do both to win. If you add to this limited time, the importance of not letting the Soviet force reach critical mass, your own supply issues and the fact that not all your units are German quality, this is a game where you will have to make decisions every turn, balancing short term and long term, and one front against the other.

Eastern Front 1941 is one of those rare games where you unknowingly take long term decisions every single turn. That tank division you used to finish off some Soviet unit in the South, well that simple tactical move locked it maybe for two turns and now you cannot redeploy it where you need your future schwerpunkt to be.

F. Final rating

Still interesting in 2021. Play it, it is abandonware anyway. It is the best game I have played so far on this blog.

I hesitate between “good” and “still interesting” but there is something subjective to this. For all its mechanical genius, I like games with a bit more meat on their bones, probably a little more of what Crawford calls “dirt” : little rules that reinforces the atmosphere.

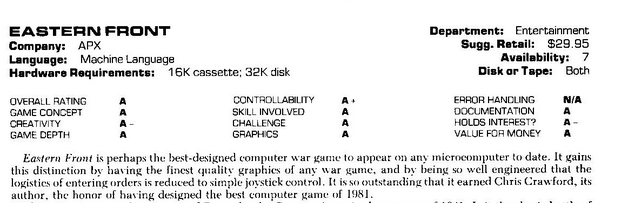

Contemporary Reviews

I found a lot of reviews for Eastern Front 1941, and none were less than ecstatic. Taking only an handful of examples :

- Byte (December 1982) : “Possibly the first fun wargame for people who hate wargames”

- Compute! (February 1982) : “[Eastern Front ]is a challenge and a showpiece for other game designers“,

- Creative Computing (January 1982) : “Nearly every aspect of the game is a technical masterpiece“,

- Electronic Fun (November 1982) : “Such play value makes even the best version of Donkey Kong pale by comparison“

Most reviews commend how immersive the game is, the smooth scrolling and how easy the game is to pick-up. Indeed, almost all reviews also mention how challenging the game is, for instance Infoworld warns (December 1981) : “Let me say it is nearly – but not quite – impossible for the Germans to win“. As an exception, Dave Meconi for Atari Connection finds that with by employing breakthrough and encirclement, Eastern Front is relatively easy to win.

Still in 1984, the Atari Book of Software would give straight As to Eastern Front 1941 – only two other games having this honor : Zork III… and Crawford’s Legionnaire.

The (then) wargaming specialist Computer Gaming World has a special place in its heart for Eastern Front 1941. It starts modestly with a “micro review” in its first issue (November – December 1981). This review starts fairly neutral in tone – but it gets more excited as it mentions the AI and concludes with “If you own an Atari personal computer you owe it to yourself to have this game. If you are considering the purchase of a personal computer but haven’t decided on which one yet, take a look at this game at your local computer store, it will make you look twice at the Atari system.” In the first year of the magazine, Eastern Front 1941 will become a common reference during reviews, and the magazine will frequently speculate on whether or not it will be ported to Apple II (it would not, due to how difficult it apparently was to scroll smoothly on that computer). Computer Gaming World also regularly featured articles on the game :

- “Beginner’s guide to strategy and tactics in Eastern Front” in issue #4 by Bob Proctor,

- A one page long letter from a reader on some advices in issue #5,

- “Scenario options” in issue #7 by Ian Chadwich – proposing to the reader to directly edit the source code to modify a few rules of the game :

Computer Gaming World would carry on giving high grades to Eastern Front : their 1991 wargame retrospective gave it 5 stars out of 5 – “the game was the first to show what the computer could do for wargaming”. It is, surprisingly, not in Computer Gaming World‘s list of “best 150 games” in November 1996 ; for reference the fun but totally forgettable NukeWar made it to the list.

As for the reception in France, the game was … almost completely ignored. The only mention I could find is a short article in the second issue of Tilt (november 1982) that gives it 4/6 in interest and states it is mostly for committed wargamers. After that it is totally missing from Tilt 1984’s retrospective on wargames. The reasons are obvious : Atari’s market share in France is only around 10% in 1981, and in the following years it would be even lower as the Commodore enjoyed tremendous success. Even for the relatively few French owners of Atari, APX did not ship outside of the USA.

Two visions for computer wargames

In the first issue of Computer Gaming World, Chris Crawford explained his vision for computer wargames : they will not be translated tabletop games but a new medium. ” Wargames on personal computers will not be just like boardgames. There are of course attempts to produce boardgames on computers, and these attempts are just as silly as the early attempts to build mechanical horses. “

In “The Art of Computer Design” (1984) he would have even harsher words, I can’t resist copying them here : ” One of the most disgusting denizens of computer gamedom is the transplanted game. This is a game design originally developed on another medium that some misguided soul has seen fit to reincarnate on a computer. The high incidence of this practice does not excuse its fundamental folly. The most generous reaction I can muster is the observation that we are in the early stages of computer game design; we have no sure guidelines and must rely on existing technologies to guide us. Some day we will look back on these early transplanted games with the same derision with which we look on early aircraft designs based on flapping wings.“

The obvious target for this attack is SSI, whose wargames had rules so detailed in the manual that one could play them directly tabletop if you had a board and counters. The most extreme case of this is of course Computer Ambush whose manual details the game rules to an absurd degree for a video game, and indeed playing the first edition tabletop could even allow faster gameplay given the extreme loading time. Robert Billings from SSI did not miss the reference obviously, and he answered in length to Crawford in the third issue of Computer Gaming World, on this topic and others : yes Crawford was right about what would come, but the technology did not allow for his vision to be true yet, and transplanted wargames were still full-fledged computer wargames.

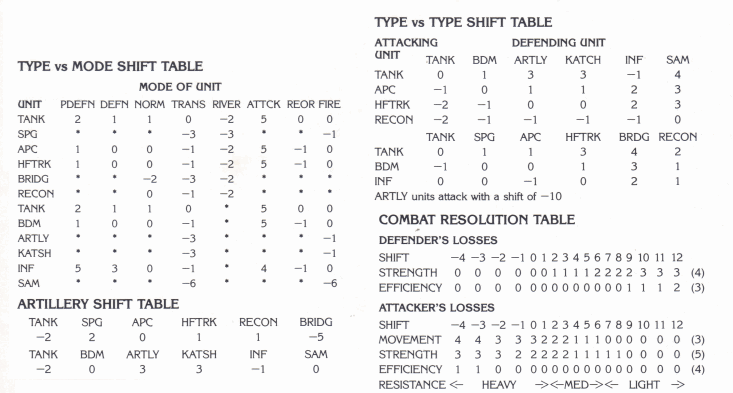

Both designs will neatly coexist in the 1980s, computer wargames that Crawford called transplants and computer wargames sui generis. Both would have their own design conventions : transplants for example used Combat Result Table (a tool that Crawford saw as allowing simple calculations that could be solved by dice, but unrealistic and unnecessary on a computer), hexagons (Crawford saw them as inferior as they did not allow to scroll smoothly) or detailed manuals explaining the rules.

It wasn’t all black and white of course, but SSI would produce mostly “transplanted” wargames, Avalon Hill a bit of both, Broderbund mostly Crawfordian wargames (typically the Ancient Art of War). As for Sid Meier, who founded Microprose in 1982, he cited Eastern Front 1941 as his main inspiration for his own wargames (NATO Commander, Crusade in Europe, …).

Crawford’s vision, of course, was vindicated : eventually many if not most wargames would become real-time – impossible on tabletop. But he was incorrect in that transplanted games were a transitional folly bound to disappear. In another genre, the Gold Box RPGs (or Baldur’s Gate) are seen as the epitome of computer RPGs even though they directly transplanted tabletop rules. In wargames, turn-based designs are still popular – you can almost hear the dice rolling in Panzer General and its numerous successors. Clearly both philosophies cohabit to this day.

10 Comments

This comes from Crawford’s philosophy of avoiding what he calls “dirt” : special rules, exceptions to the general cases, etc.

LOL wargamers call this “chrome”. You gotta have chrome, otherwise you end up with a dull abstract game.

Consider the case below : the tank corp attacks an enemy, chases it and follows it. The infantry behind the tank corps follows, as ordered. The tank carries on the attack, more pursuit, except this time the zones of control of the Soviet units above and below stop the infantry from following, and the tank is badly isolated.

Later games got rid of this problem with a “breakthrough” rule, in which a panzer corps doesn’t need to be supplied for one turn when behind enemy lines.

“hexagons (Crawford saw them as inferior as they did not allow to scroll smoothly)”

Probably dumb question, but why would hexagons impede smooth scrolling?

” Probably dumb question, but why would hexagons impede smooth scrolling?”

Not a dumb question at all. The problem was that the display hardware and software were organized around a rectgrid (pixels in simple (x, y) locations). It was certainly possible to use hex grids — I did that in one of my games. But you were fighting against the grain of the system, and in those days, the software was running just barely faster than the hardware, so the additional time requirements of the hex grid were the source of endless headaches.

I actually solved the mathematical problems of the hex grid back in 1978, and had hex grid algorithms running on my KIM-1 system back then.

In the 1970s, boardgame designers had two terms: color and dirt. Color described those elements of the game that gave it a realistic feel. Dirt described picky-picky rules that added complexity to the design. The goal was to achieve the maximum ratio of color to dirt.

Chris, if I may ask, do you remember who were considered to be the authoritative historians of the Eastern Front in wargaming circles in the 70s and 80s, and how has the view on Barbarossa changed in the intervening decades? Who were your own most influential sources, and are there any particular books that changed your views or gave you new insights?

The Myth of the Eastern Front was a fascinating book to me, and it touched on wargaming, albeit only lightly. I have a decent bead on the current scholarship by people like Glantz and Stahel, but only a vague understanding of what the general view was before the end of the Cold War, and the opening of Soviet archives. Especially from a wargaming perspective.

Klaus, that’s a tough question to answer, because I wasn’t following the scholarship. Moreover, I can’t even recall the titles or authors of the books that I read in preparing the game. I went down to my library and dug around; the World War II book are all on the highest (least used) shelf. I saw von Manstein’s book, and von Mellenthin’s and Guderian’s. Paul Carell’s two books also (Hitler Moves East 1941-43 and another) I have a bunch of first-person German accounts such as Guy Sajer’s The Forgotten Soldier and another one “Enemies are Human” There are also a bunch of general accounts. As you imply, we didn’t have much from the Soviet side. So yes, we relied almost entirely on the German accounts.

Thanks for getting back to me. John Erickson’s Road to Stalingrad came out in ’75 and would have been available, but Road to Berlin was only released in 1983. He probably was the first Western historian with a good access to Soviet sources.

I never read Carell, but I’d be wary of him. He was an SS-officer and Nazi propagandist, and from what I’ve read, he didn’t change his views much after the war.

[…] Dow for talking through ideas. You can once again find posts at The Wargaming Scribe on Eastern Front 1941 that better explains how the game actually plays and its historical importance within wargaming. If […]

Necro!

I wanted to bring up a thing about ZOC weirdness because this has been an issue for me in the expert modes. You mentioned this in Systems, but we can see strange results from the other side as well!

Take this four-way pincer:

https://imgur.com/a/53Xbt0M

The Soviet infantry in the middle can escape by pushing his way out east, destroying one of my infantry and moving right through the ZOC. This sort of thing happens to me with some regularity, as low-muster units aren’t good for much except supply cutoff (and sneaky captures).

But now let’s say we have a two-way pincer:

https://imgur.com/a/Ij131em

An escape to the east or west is impossible.

Hypothetically, what if the rule was that you can attack a unit in a ZOC, and even force a retreat if your attack brings it to the breaking point, but you cannot follow? ZOC of the unit you pushed would be ignored; ZOC of other units would not be. So in the top image, the Soviet infantry could attack and destroy the infantry to its right, since it has nowhere to run, but would not move into its place. Would that be realistic? Seems it might partly solve the “tank pushed too far and got itself isolated” problem, as well as the above one.

You are right indeed to note this inconsistency. It is not specific to EF1941, even recent games have this flow – eg Order of Battle (or generally all Panzer General clones) allows you to escape encirclement between two units by pushing a third one. Unity of Command uses your solution, and it works perfectly… but UoC2 is two orders of magnitude more complex than PG clones. I think the problem is also found in most tabletop wargames with ZOC.

Generally speaking, ZOC and simultaneous turn resolution don’t interact well. A solution could have been soft ZOCs (units take damage/fatigue when moving within an enemy ZOC) – but then that’s the solution chosen by Gary Grigsby’s Objective Kursk and it does not work well either as full units can dissolve without combat it they move to the wrong place. Not ideal. Soft ZOC and short turns? Game too long. Your solution? Maybe the best one, but it may turn the game into WW1 as it would take a long time to repeatedly “push the frontline” (you need to dislodge two adjacent units, by the time the second one is dislodged the first one has reorganized so now you need to fight it again).

Generally speaking, I dont think simultaneous resolution works very well at that scale – lots of units, lots of degrees of freedom for them. If you want divisional level you need to have fewer “units” to control and less detailed orders – the AGEOD/SGS system comes to mind.

In any case, Crawford made it work, because he was that talented, because not all design issues need to be fixed and because in 1981 there was no cwargame even coming close. Still, I think that two years later Crawford would have made EF1981 real-time-with-pause.