Part of my series on national beginnings: Spain – Argentina – Uruguay – France

Currently stuck between a monster wargame (Gulf Strike) and a Civ-like (Incunabula), I looked for short articles to fill the gap, and so selected a Spanish game called Reyes y Castillos. However, as I was playing it, I found the Spanish difficult to read, odd (“lo hizo de goma“, “sonaste macho“) and full of words I had never heard before (“amarrete“, “linyera“). I initially attributed that to how rusty my Spanish is, then to odd colloquialisms of the early 80s. However, when I finally accepted I did not understand the game, I asked a certain artificial friend for help, he made me realize I had chanced upon my first Argentinian game.

[Addendum 14/09/2025: Reyes y Castillos was eventually covered here]

Prologue: My Darling Clementina

The history of computing in Argentina really starts in 1961, when mathematician Manuel Sadosky and his team at the Calculus Institute of the University of Buenos Aires finished setting up a Ferranti Mercury computer. This specific machine came with the song “Oh My Darling, Clementine” pre-programmed. The rendition was crude, but impressive enough to give the computer a name: Clementina.

This auspicious beginning was brutally interrupted by the (right-wing) 1966 Revolución Argentina coup and the Night of the Long Batons that followed. Most the the staff of the Calculus Institute either left or were expelled, Sadosky exiled to Uruguay where, of course, he helped build the first national computer in 1968 (the unimaginatively named “la máquina“), before leaving again for Venezuela (which already had a computer so Sadosky could not complete a Bolivarian computing slam) and ultimately Spain. As for Clementina, she was eventually dismantled by 1970.

The simmering years of Argentinian computing

The regime wasn’t anti-technology; it was against technology controlled by left-wing university types. It therefore kept supporting the electronics industry and computer science. Policy-wise, that meant duty-free import of components but high import taxes on assembled hardware; this pattern continued after the regime fell through the terms of Juan Perón and then Isabel Perón (1973–1976).

This was before home computing, but the strategy fit early 70s consumer electronics and put Argentina in a decent position for the coming microcomputer wave. There was even a budding domestic console scene: the Videojuel in 1975 (a Magnavox Odyssey clone) and the more successful Telematch in 1976. And in 1976 or 1977, right on cue, Micro Sistemas in Córdoba began work on a domestic computer that hit the market in July 1978: the MS101.

We’ll never know how it might have fared, because the March 1976 military coup happened. The new regime, with José A. Martínez de Hoz as economy minister, implemented free-market reforms and trade liberalization. Tariffs and import controls were slashed, the peso soared, and importing foreign electronics suddenly became cheaper than ever. Domestic production couldn’t compete. Fewer than 400 MS101s were sold – and that’s still more than the Micro Sistemas machines that followed. It wasn’t an isolated case: Olivetti Argentina (typewriters and calculators) folded in 1979. The 1980 banking crisis put a final nail in the coffin of domestic industry, at the worst possible time for computing.

It is hard to say how many computers there were in Argentina in the early 80s. The subsecretaría de informática published annual reports on the size of the parque computacional argentino, but they only tracked computers used by private companies and public institutions. Until 1981 the reports counted only mainframes and minicomputers (around 6000 in 1981-1982). Starting October 1982, they added personal computers: roughly 900 (mostly in the private sector) in October 1982, growing to 3000 by April 1983. These reports did not include home machines, but given prices, the household install base must have been tiny.

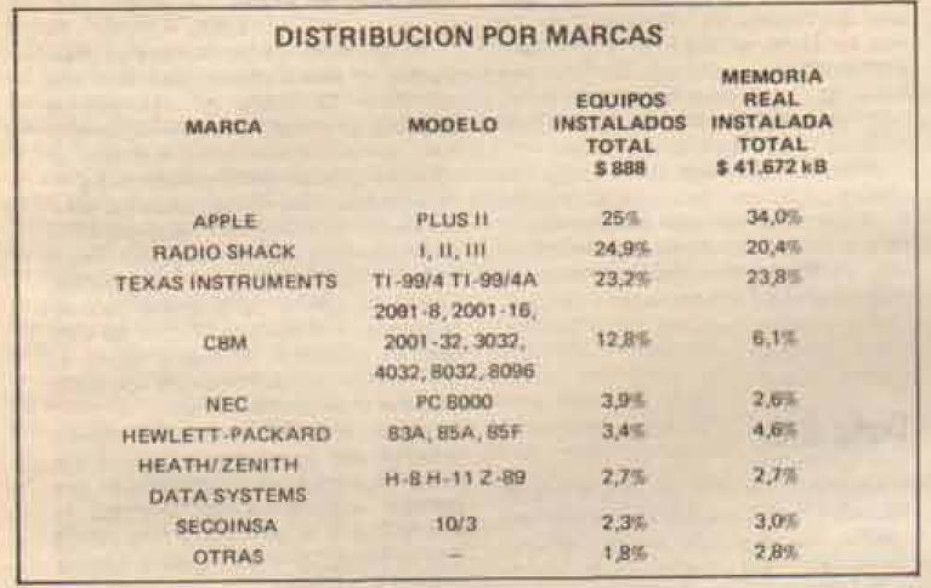

Rule changes always mint winners and losers. Ending tariffs crushed domestic producers but kick-started personal computing in Argentina. In 1982–1983 it was still a slow simmer: despite the strong peso, Argentina was a poor country and the first movers clustered at the cheap end. While hard data is scarce, two leaders seem to have emerged in the still-tiny market: Texas Instruments with a TI-99/4A assembled locally to Argentine specs, and the TK83, an even cheaper unauthorized ZX81 clone from the Brazilian Microdigital. Beyond those, the TRS-80 had a presence thanks to an early popularity with private companies , and the Apple II rallied the usual but in this case very small cadre of enthusiasts. Volumes were low, but an ecosystem was forming, including the first non-professional computer magazine: Micro Computación, whose first issue was dated September 1982.

The maturation of a market of clones

The home-computing explosion would wait a few more years. By 1984, democracy had returned, and with it our friend Sadosky, now Secretary of State for Science and Technology. He launched the Programa Nacional de Informática y Electrónica (PNIE), a broad push to expand computing at all levels (grants for private companies, scholarships, informatisation of select schools,…). He also wanted to rebuild a national computer industry, so the government temporarily banned imports of complete computers, a ban that conveniently also helped the balance of payments. This created an unique characteristic of the Argentinian market: the domination of clones, of which four series would dominate the Argentinian markets until the end of the 80s:

- The Microdigital clones, by 1985 the TK83 had been joined by the TK85 (another ZX81 clone) and would soon be joined by the TK90X (a ZX Spectrum clone),

- The Czerweny clones. Czerweny had been an industrial and household equipment company whose activity had plummeted, like everyone else in this sector, because of the De Hoz reforms. Czerweny turned around toward distribution, and in particular planned to import Sinclair computers to Argentina. Sinclair was interested, but in 1982–1983 a certain set of islands in the South Atlantic made importing anything from the UK impossible. The workaround, proposed by Sinclair Research, was to use the Timex Sinclair joint-venture to import key components for local assembly under the Czerweny brand. It took time to set up, but in 1985 the CZ1000 and CZ1500 (Timex Sinclair 1000/1500 derivatives – also ZX81 clones) arrived. Czerweny quickly took independence from Timex, notably with a Spectrum clone (CZ2000). The company overtook Microdigital and produced up to 4 000 computers per month before shutting down in 1986 after a fire at its Gálvez plant.

- The Drean Commodore. Drean was a home appliance company that negotiated exclusive importation rights with Commodore, and assembled locally Commodores with Argentinian specifications under the name Drean Commodore. Both the C16 and the C64 were released in 1985, and the Drean C64 would become, in time, the most popular Argentinian home computer with 10 000 units rolling out every month by 1986.

- Finally, a company called Telemática sold the Talent DPC-200, a local production of a Korean MSX design, and with it managed to bag in 1986 the PNIE contract to provide Argentinian schools with tens of thousands of units, a feat that allowed it to have a significant presence until the end of the decade – 60 000 machines in total according to its founder Carlos Manzanedo.

In addition to these computers, Timex managed to sell the T/S 2068 (another ZX Spectrum clone) despite local regulations, and the Argentinian branch of Texas Instruments continued to produce the TI/99A until possibly 1985 if not 1986, long after its production had ceased in the US. This line-up remained remarkably stable from 1985 to late 1988 with ZX-81 clones remaining on the shelves and covered by local magazines years after that computer had reached total obsolescence in other countries.

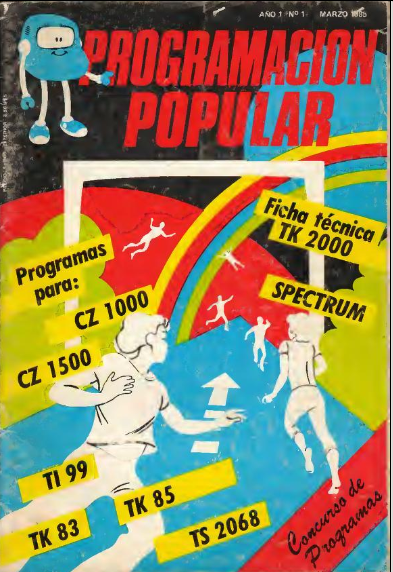

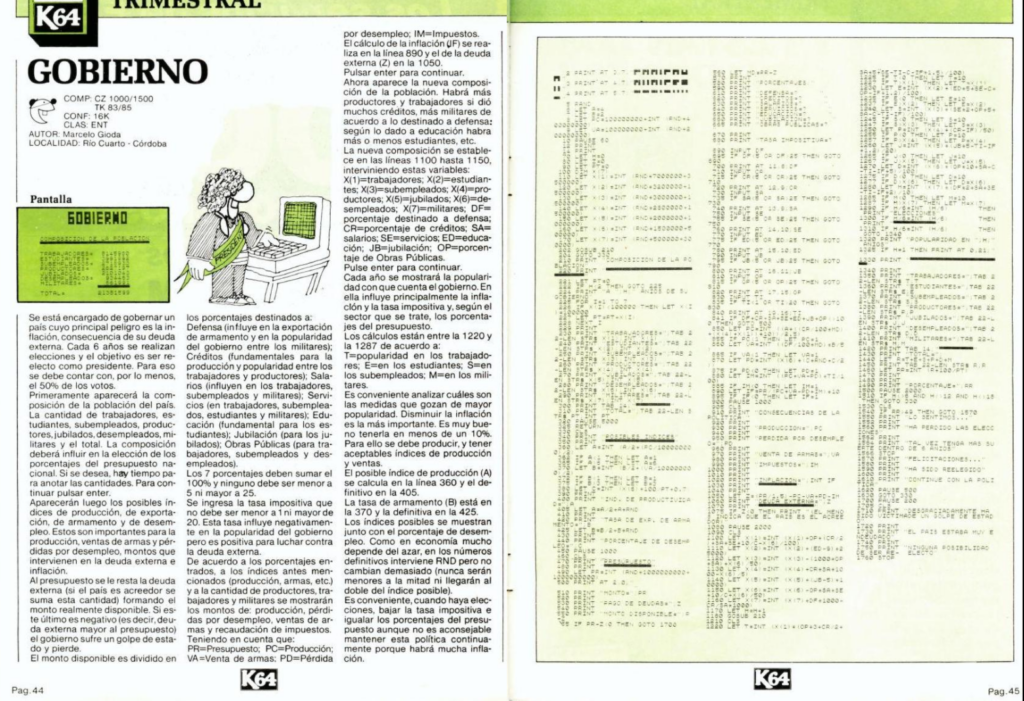

So, for our period of interest, Argentina was a Commodore–ZX country with a sprinkle of TI-99/4A and MSX computers entrenched in schools. Which brings us back to the pivotal 1985. The flood of models, plus Sadosky’s policies (most schools started to get computers, sometimes a lot of them!), triggered the real cultural deflagration other countries had enjoyed earlier. Computers became a common item, and several major magazines launched that year: Programación Popular (March 1985), K64 (April 1985), and Drean Commodore (December 1985), followed a bit later by Load MSX (May 1986). For the first time in Argentina, mainstream magazines devoted a significant share of their pages to gaming.

Aaarrrr! Early computer gaming in Argentina

What strikes you immediately when browsing Argentinian magazines is how few ads for games there are. American or British magazines have full pages of game ads, big and small. Argentinian magazines from the 80s, whatever the year, barely have any, even in relatively casual outlets like K64 or Drean Commodore 64. I sometimes found one ad per issue, more often zero, and exceptionally two.

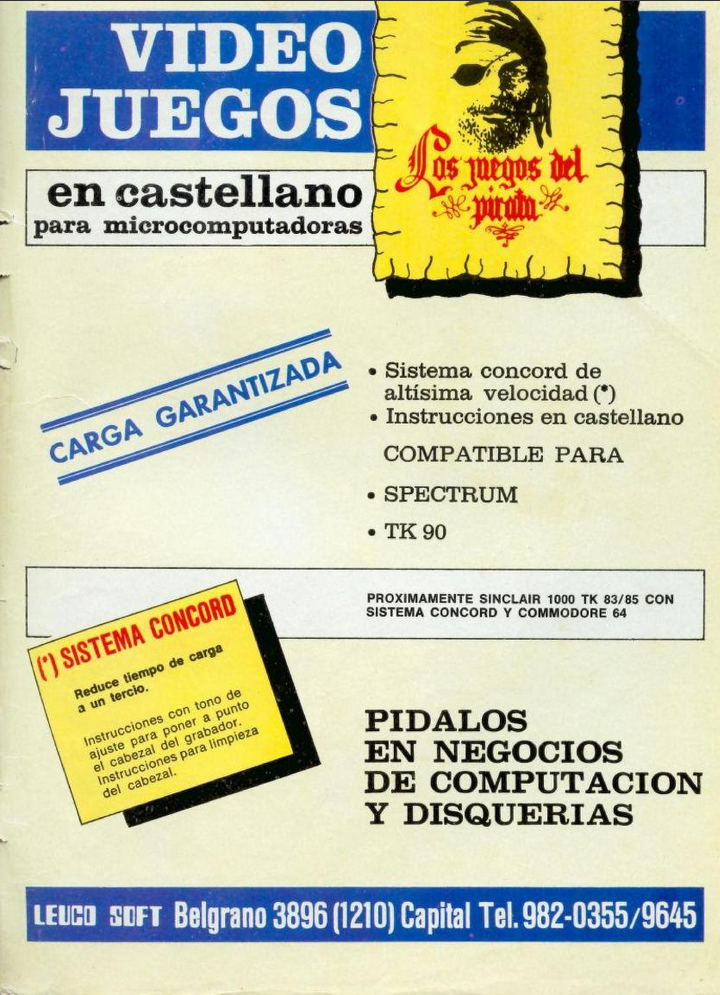

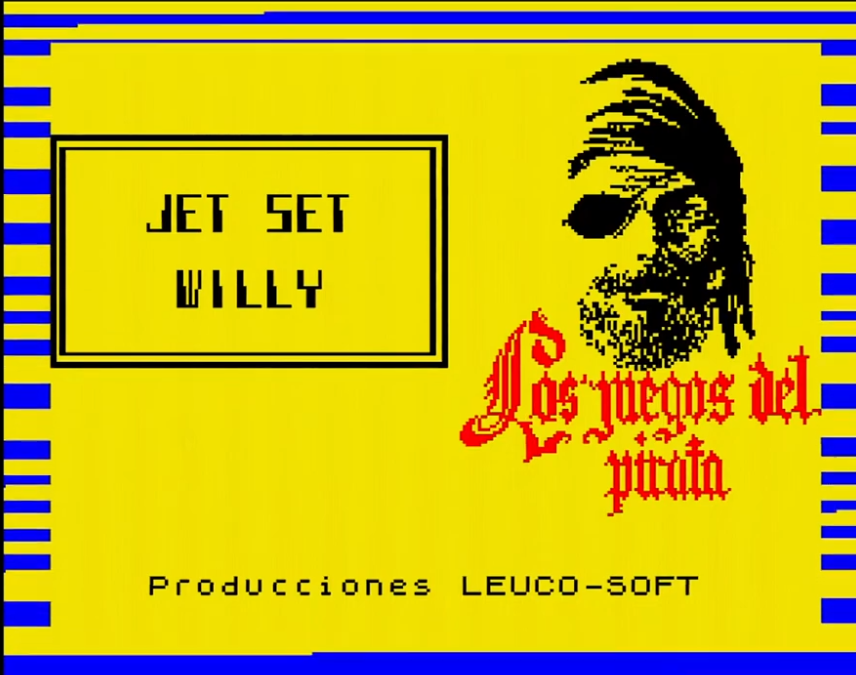

Most of the 1985 ads are for Leuco Soft, which proposed “los juegos del pirata“. This was an interesting branding, given the “juegos del pirata” were the popular British games unofficially translated into Argentinian and sold without regards to the licence owners.

Does that mean Argentinians were all work and no play? Possibly a bit more so than the British and the Americans, but not decisively. The magazines, particularly Drean Commodore and Load MSX, featured complete reviews of imported video games; more importantly, Argentinian games – and throngs of them – appeared as type-in listings, just like in the UK. Argentina had, however, a unique innovation the UK did not: in 1986 K64 partnered with a Buenos Aires FM station to broadcast computer programs over the airwaves. Early-morning listeners could record the audio to cassette and then load it into their computers, effectively downloading games through their radio.

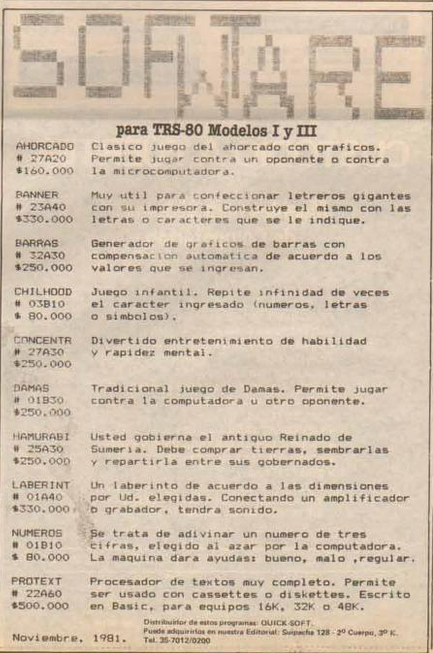

I said earlier on that there were no ads for games in magazines, but I lied. There were, but not of the sort you expect. Instead, ads for video games looked like this:

Throughout this period, the vast majority of games “sold” in Argentina were unofficial copies of foreign titles. Many computer shops doubled as exchange clubs: you’d buy hardware and leave with a handful of dubbed tapes – sometimes even with Spanish instructions. If you didn’t want to set foot in a hardware shop, there were well-known spots where you brought a blank cassette and some cash and had it filled with whatever UK/US release you asked for.

This is a key reason for which there was no Argentinian video game company: no domestic market. As for the foreign markets, the nature of the installed base made it difficult to replicate the Spanish miracle: the TI-99/4A and the ZX81 clones had reached the end of their shelf life everywhere else, the TK90X and T/S 2068 were not compatible with the Spectrum out of the box, and finally the MSX natural habitats were countries with vastly different cultures. This left only the CZ2000 (a true Spectrum) and the Commodore 64 (with its immense international competition) as possible export markets. This was obviously not enough, and exports did not happen

Still, there was one game that could not be simply pirated from Europe or USA, and this brings me to the first Argentinian game.

The first Argentinian game

Technically, the games embedded on the Argentinian console consoles were the first Argentinian games, but they were mere clones of the ones found on the Magnavox Odyssey, with the sole exception being – this is Argentina after all – a game called Fútbol. As it were Fútbol, was the clone of a game made for the Overkal, a forgotten 1973 Spanish clone of the same Magnavox Odyssey. I suppose this makes Fútbol the first Spanish video game, and I should update my earlier article on Spain, but in any case I don’t consider any of those titles Argentinian. The first Argentinian game was therefore not about Fútbol, but about another game endemic in Argentina and Uruguay: Truco.

Truco is a fast-paced 2v2 bluffing card game played with a 40-card Spanish deck, which involves, just like poker, bids and deception to win. In early 1982, Enrique Arbiser and his nephew Ariel Arbiser spent weekends playing games together. Enrique was one of the rare Argentinian computer scientists, having learned to program in assembler while working for IBM at 22, back in the early 60s. Sixteen-year-old Ariel had taught himself BASIC and then assembler the year before, on one of the few TRS-80s in Argentina. Given their skills, they also liked to program together, though few projects were finished beyond a couple of unpublished dice games. That’s when Enrique, a self-described lifelong Truco enthusiast, proposed something more ambitious: a Truco game.

Over several months, they coded it bit by bit and finished before the end of 1982. It was probably the first Truco on a computer, but that’s not what made it special. This first Truco also had an AI opponent that not only played well but taunted the player as it played – almost like a real human opponent by 1982 standards. I am not sure how this first TRS-80 Truco Arbiser was distributed; I don’t believe it was even sold. Instead, it was (probably) distributed freely within the hobbyist community. This attracted the attention of Texas Instrument Argentina, who asked them for TI-99/4A version for cartridge they would sell directly. Those versions were published in 1983, and that’s the version recognized by the contemporary Asociación de Desarrolladores de Videojuegos Argentina as representing the first commercial Argentinian game. Unfortunately, both the TI-99/4A and the TRS-80 versions are now lost media.

The TI-99/4A Truco was the first one, but it was not the one that all the gaming Argentinians remembered. This privilege goes to DOS version, released in 1984 and then maintained until the 90s (with a speech synthetizer added for instance in 1992). This version was allegedly the most pirated game in Argentina, but in exchange became, to quote a research paper by Gustavo del Dago on the game, an “iconic video game at the national level.”

That’s all for Argentina, The next article will be short notes on its neighbour Uruguay, and then we’ll be back into wargames or wargame-adjacent games with Reyes y Castillos.

Sources

On the Clementina:

The Beginning of Computers in Argentina and the Experience of the Calculus Institute at the University of Buenos Aires, Raul Carnota, 2015

“Clementina”: la primera computadora científica de Argentina sin teclado ni monitor cumple 61 años, La Voz, 2022

The Beginning of Computer Science in Argentina – Clementina – (1961-1966) A Personal Experience, Cecilia Berdichevsky, 2006

Some Aspects of the Argentine Reception of the Computer, Nicolás Babini, 2006

On the 70s and early 80s

La Argentina y la computadora: crónica de una frustración, Nicolás Babini and Carlos Vilensky, 2003

Microsistemas, ese hito olvidado de la computación en la Argentina, La Nacion, 2017,

Empresas nacionales, micro-computadoras y MicroSistemas S.A, Karina Bianculli, 2021

Mundo Informatico 53 and 66( parque computacional argentino

Mundo Informatico 83 (January 1984) on the ban of computer importations

Desindustrialización y retroceso tecnológico en Argentina, Hugo Nochteff, 1984

Breve repaso histórico de la computación hogareña en la Argentina, Guido Caso, 2011 (warning: lots of dates are off)

MSXViva, El lado oculto en la historia de la Talent MSX en Argentina, 2016 from which I pull the 60 000 units for the Talent

Made in Argentina, Compuclassico

La Spectrum in Argentina, for a short testimony on piracy in Argentina

Revista K64 and CZ, la Spectrum Argentina on HomeComputer.com.ar

La Commodore 64 cumplió 35 años, La Nacion, Augusto Finocchiaro Preci, 2017

Several articles in Programación Popular and K64 that alas I haven’t consistently recorded

Overkall (1973), Videojuel (1975) and Telematch (1976), PrehistoricGaming.com

On Truco Arbiser:

Interview of the Arbiser only found on the Internet Archive, 2002

Home Page del Truco Arbiser

De la programación hogareña al primer videojuego comercial latinoamericano. Análisis y estudio del Truco Arbiser, Gustavo del Dago, Universidad Nacional de la Plata

12 Comments

Loving these articles about national “firsts”! I look forward to reading the one on Uruguay 🙂

Superb work sir.

I really enjoy these national retrospectives.

I found the Spanish difficult to read, odd (“lo hizo de goma“, “sonaste macho“)

To be fair, a lot of these early 8-bit bedroom-developed games have awkward/badly written English. It wouldn’t surprise me if some of them had bad Spanish too, or even just nonstandard out of technical necessity. I’m curious about the context of these examples, because to my eyes and without context, the first one at least parses normally.

It lunfardo https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lunfardo

Those sentences are from “Lunfardo”. This is like a set of slang words that originated in Buenos Aires, Argentina mostly between immigrants and working class people in the end of 19th century. It is also associated with Tango (music) lyrics. It is common to use a lot of these words when you play Truco.

“Lo hizo de goma” means that you win (something, in this case a Truco game) with a lot of difference between you and your opponent.

“Sonaste macho” is a bit harder to explain, macho is male and sonaste is something that makes a sound. When someone says “sonaste macho” related to playing a game of Truco, it is telling you that you are gonna lose that game, that he has better cards. It is used to trick other players too.

Yes, it parses… but the meaning in the dictionary is different to the real meaning of the phrase in Argentina: “lo hizo de goma” means in Spanish “he/she made it out of rubber”, but the real, street-wise meaning in Argentina is “he/she destroyed it”.

Thanks, this article is great! I had missed the article about Spain and will be happy to recover it.

> Early-morning listeners could record the audio to cassette and then load it into their computers, effectively downloading games through their radio.

This sounds awesome to me and I’m sure the people using the service must have felt the same. Though, remembering the sound of Spectrum cassettes, their family members and life partners could have held a different opinion.

The part about piracy and consequent lack of a domestic game industry reminded me of the famous saying that Argentinian are Italian who speak Spanish (while believeving to be English). It also made me think of a meme:

Crying Wojak: – Noooooo, you cannot use the word “piracy” to refer to copyright infringement. That’s a disparaging term used by companies to defend their monopoly and prevent users to…

Argentinian Chad: – Los juegos del pirata!

I had never heard about Truco before, and now I encountered it twice in the span of a week, first in your blog and now in a post currently near the top of HN: https://marianogappa.github.io/software/2025/08/24/i-made-two-card-games-in-go/

Maybe a case of Baader–Meinhof phenomenon.

By the way, I just made a micro-review of the DOS game Battle Ground on my blog (https://twostopbits.com/item?id=6602), to spare you and your teammates the effort 🙂

Thanks for dropping by. I already stumbled upon your site a few months ago, while looking for documentation on the racing game Stunts (specifically I wanted to know whether the playstyles of the different AI opponents was documented). Fun fact: for a short time in very early Internet, I had the Internet record of the shortest time on the Default map, because we had a fierce competition with my brother on having the shortest time, which he dominated until I found a shortcut that did not give you a time-penalty as it should have. This ended the competition with my brother (neither of us wanted to have a “best use of an exploit” competition), but I uploaded a replay on an early Stunts site (I can’t possibly remember which one – it was >20 years ago).

Tout se tient, alors. Concerning Stunts’ opponents there is a very good video showing the differences. You probably already found it but anyway: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kmP0uAxz8Dc

There is even a program allowing you to change the AI of each opponent: the parameters are just the max speed at which each pilot is allowed to drive on specific track elements.

The record on Default is currently about 30 seconds. Exploits were harmed in the process 🙂 But feel free to drop by if you ever need a break from your favourite genre! There are tournaments with different racing styles allowing more or less abuse on the game mechanics.

And thanks, as always, for your work!

Nice work! I love how you used my info on the Videojuel!

If you want to extend and amplify your post regarding the origins of videogames in Spain there is this article i recently written about that regard (in Castilian Spanish). You can take the info with the corresponding quote:

I’m also the biggest responsable on writing the history of the Overkal as you can possibly make out. I also wrote about the origins of Segasa and early vídeo game systems of Spain.

Truco was very popular among the students of Escola Politécnica of the Universidade de São Paulo and I seem to remember seeing in 1981 an implementation on the university’s Burroughs B6700 mainframe computer. It was a text only version using a terminal. I didn’t pay much attention at the time and so don’t remember if it had a computer opponent or not.