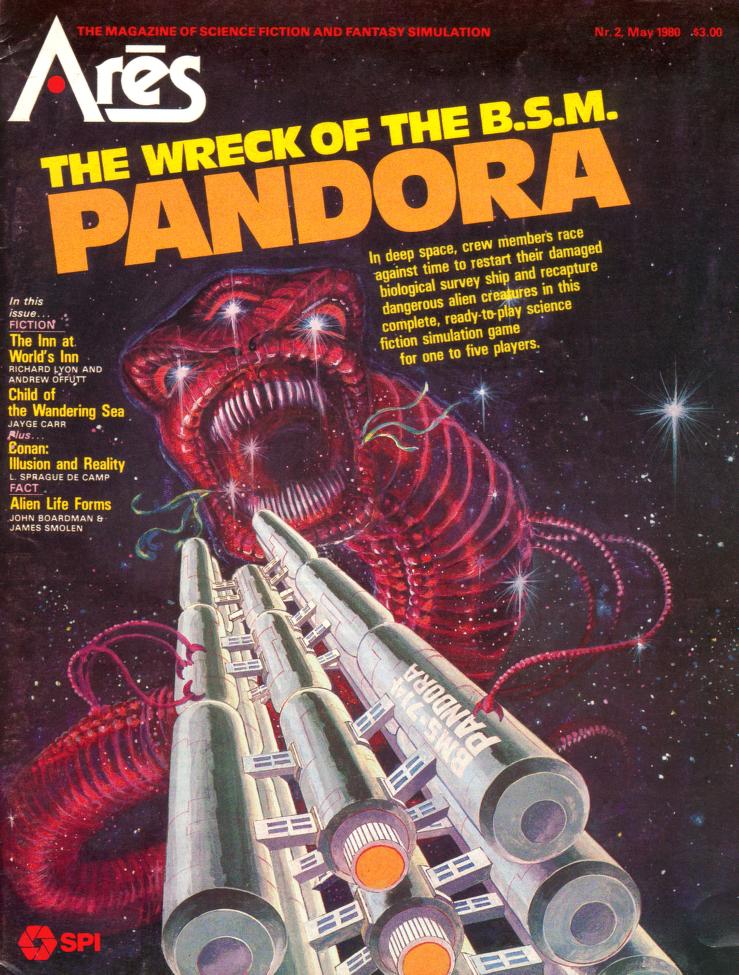

The Wreck of the B.S.M. Pandora by SPI, published by Special Delivery Software

First release : Spring 1982 on Apple II,

Tested on : AppleWin emulator

Total time tested : 5 hours

Average duration of a campaign: 45 minutes (3 crewmembers who make it until the end)

Complexity: Average (2/5)

Would recommend to a modern player : Yes

Would recommend to a designer : Absolutely

Final Rating: Good !

Ranking at the time of review : 1/58

As usual, this review assumes you read the AAR for the game.

The Wreck of the B.S.M. Pandora boardgame was immensely popular, and it’s not a surprise it was ported on a computer. What is way more mysterious is how it ended up on Apple’s Special Delivery Software catalogue. But let’s start with the boardgame itself, it is a good opportunity – the only opportunity – to talk about Simulations Publications Inc, better known as SPI.

To talk about SPI, we need to take a short detour via Avalon Hill. Avalon Hill had been founded back in 1953 by Charles Roberts and was for a long time the only wargame publisher. After some difficulties in the early 60s, Avalon Hill changed its strategy : as the only wargame publisher it was in its interest to organize the sprouting community around itself – both to accelerate its growth and to create a barrier to entry against newcomers – and so it started publishing The General magazine in 1964. The General also allowed Avalon Hill to maintain its slow release schedule (one or two games a year, as production & distribution costs were high and Avalon Hill’s management feared cannibalization) by providing scenarios or variations on the existing games. You may remember one such example on this blog : Pursuit of the Graf Spee was based on a variant for the Bismarck boardgame that Joel Billings found in the July 1979 issue of The General.

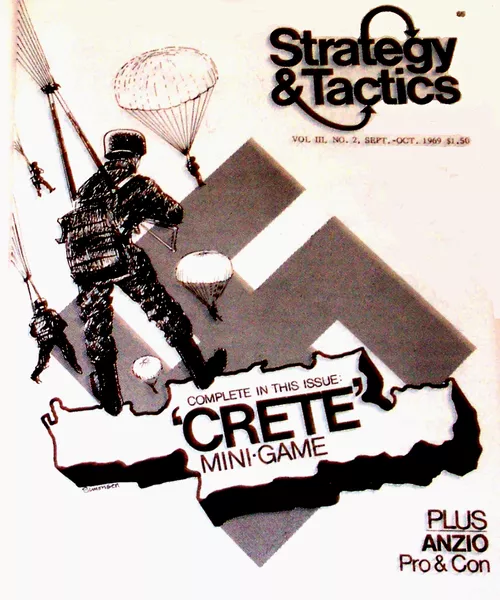

The clench The General had on the hobby did not stop fanzines from appearing, and one of them was Strategy & Tactics, which started in 1966. After a few difficult years, Strategy & Tactics was taken over in 1969 by James F. Dunnigan and Redmond Simonsen – respectively former designer and artist for Avalon Hill and who had just founded SPI. The duo believed that the market for wargames was much deeper than what Avalon Hill believed, and could absorb several wargames a year. There was, of course, the question of distribution, but as they envisioned it Strategy & Tactics would solve that. Not only because Strategy & Tactics would advertise their games and create a community like The General did for Avalon Hill, no. They were bolder : starting from September 1969 Strategy & Tactics would include one wargame, complete with map & counters, attached to the central page. As Jon Freeman stated in his Complete Book of Wargames :

“SPI simply exploded. Producing more than a dozen games a year, SPI attained something approaching parity with its older rival within three years The magazine proved invaluable. Strategy & Tactics attracted subscribers with a taste for SPI products, provided free advertising for SPI games, generated steady income, and through a formal feedback system allowed SPI to produce games with a predetermined market.“

SPI rode a high tide in the early and mid-70s in a thriving market, but started to have financial difficulties in the late 70s. By Simonsen’s own admission, SPI’s management lacked business expertise and started accumulating mistakes : too many games, low or even negative margins on some products (famously on the popular 6$ “capsule games”), failure to adjust prices with inflation and, worse, poor cash and inventory management as they tried to move into traditional distribution. In one famous instance, they printed 80 000 copies of a Dallas RPG. “That was about 79 999 more than anyone wanted“, quipped Simonsen. As demand stalled and inflation set-in, SPI started to lose a lot of money.

What SPI would have needed was a streamlining of its operation. Instead, it tried to find a new audience by investing in new genres : fantasy, “politics”, science-fiction, whatever, sometimes as wargames and sometimes as more traditional boardgames. Browsing quickly through SPI’s catalogues, I could find 1 “SF & Fantasy” game in 1975 (Starforce), 8 in 1977, 11 in 1978. The effort was significant but not massive nor really coherent ; it was more of a “throw everything at the wall and see what sticks” approach. And sci-fi games stuck – in the 70s sci-fi was all the rage, there is a reason why there was a publication called “The Space Gamer” from 1975 to 1985.

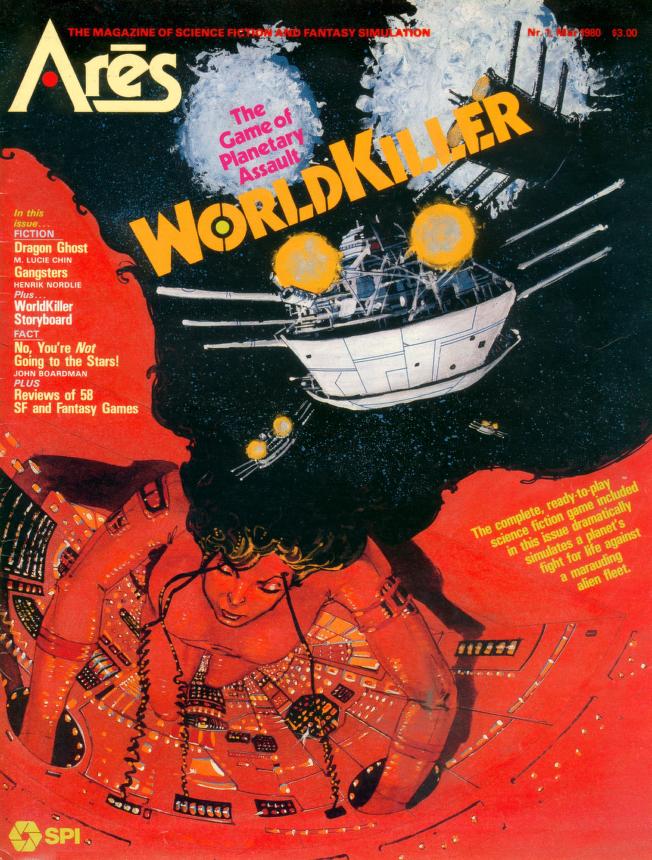

Of course, SPI was a minor player on the sci-fi gaming market. In an effort to lead the wave rather than follow it, Dunnigan proposed to recreate the miracle it had achieved 10 years earlier and publish the Strategy & Tactics of sci-fi. Simonsen liked the idea and came up with a name : Arès. With Dunnigan doing the marketing and Simonsen as editor and art director, the first Arès was launched on March 1980. Each issue of Arès included a mixt of reviews, short stories, science essays and, of course, a complete game. The first one was WorldKiller – apparently a mediocre game – two months later the second issue proposed The Wreck of the B.S.M. Pandora.

Like so many SPI games, the Wreck of the B.S.M. Pandora was designed by Dunnigan and illustrated by Simonsen. Of course, the fact that the co-founders and top management of SPI, as incredibly talented as they were, still designed games in great numbers in addition to all their other tasks was certainly another part of the problem.

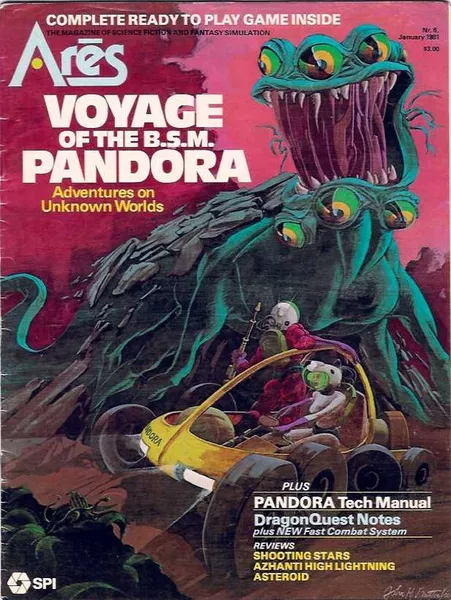

I don’t really need to explain the board game – it is quite close to the computer version – the few differences I will explain later. Moreover, Quarter To Three did a very good coverage, including an After Action Report . Suffice to say it was extremely popular, in particular in solitaire, so much so that it received a prequel as early as January 1981 (the Voyage of the B.S.M. Pandora) which could only be played alone.

As for the PC port, now we’re getting into uncharted territory. The management of SPI was familiar with computers : in the late 70s SPI used TRS-80s for rule preparation and Dunnigan himself was regularly giving a talk called “Napoleon at IBM” on what computer wargaming would be. Well aware of the capabilities of the Apple II, Dunnigan did not consider the technology ready for satisfying wargames in the late 70s. But somewhere after the launch of Arès, Dunnigan and Simonsen decided to branch into videogames.

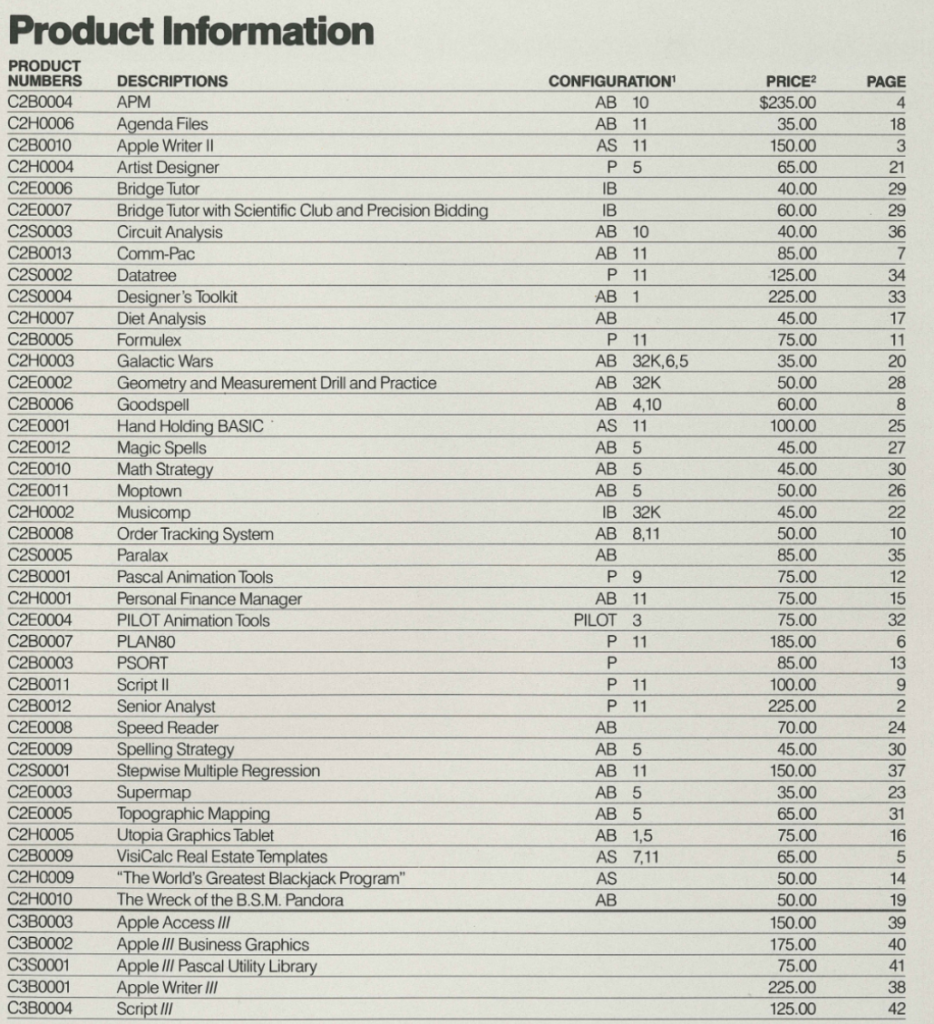

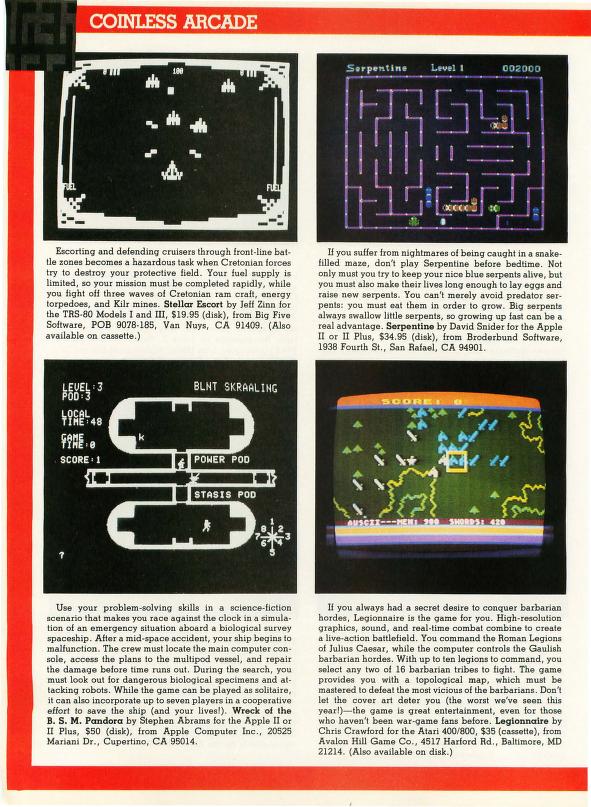

The port is credited to Simonsen himself (“creative direction, graphics, documentation“) and Stephen Abrams (“software design“). I could not find any information on Abrams (edit October 2024: Well, I could after all, and he’s significant on his own), but Dunnigan told me that at that time a lot of SPI customers were software engineers and approached SPI to help them make computer games, so possibly this is how Abrams was onboarded on the project. The publisher is Special Delivery Software, a short-lived division of Apple which shut down shortly after releasing a Winter 1982 catalogue. Checking the Spring 1982 catalogue of Special Delivery Software, the Wreck of the B.S.M. Pandora stands out : out of more than 40 software programs there are only 3 games (excluding children’s learning programs), the rest of them bearing serious names like “VisiCalc Real Estate Templates”, “Diet Analysis“, “Personal Finance Managers” or “Geometry and Measurement Drill and Practice“. Why SPI decided to publish its game with Apple rather than with a specialist like SSI or Epyx defeats imagination.

The game also seems to have been rushed, and barely playtested : it has several major bugs and design flaws that would not have passed the shortest playtest. I suppose the designers were well aware and did not have the time to fix them due to SPI’s absolutely desperate situation at that point : SPI ran out of cash in March 1982, was foreclosed the 31st of March and de facto acquired by its creditor TSR in the first days of April, Simonsen himself was fired the 30th of April. Wreck of the B.S.M. Pandora was released in Spring 1982 ; I don’t know the exact date but it is either just before or during these events.

This was a long intro, so let’s move to the review.

A. Immersion

The Wreck of the B.S.M. Pandora has decent graphics for 1982 (with a nice diversity of aliens), but well, it’s still 1982. On the other hand, it has an atmosphere : you move slowly through the corridors, open the airlock one after the other not sure what to expect, and wonder whether the alien will ignore you or attack you. That allows it to punch above its weight.

Rating : Acceptable – It’s hard to go higher when the palette has two colours and the items are just letters.

B. UI, Clarity of rules and outcomes.

The game is complex, but quite easy to play once you remember the keyboard commands. It really lacks two things :

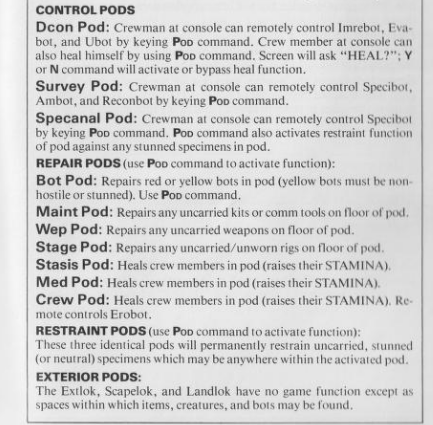

- In-game information on what all the various items and pods do. Checking the manual to check the stats of a robot, the effects of an item or which pod controls which robot can get old :

- Similarly, and I realize this is not something games did in 1982, yet I wish the game recorded what you know (ideally with a map), for instance the condition of the items and pods you examined. Note that the nature of a pod remains displayed if a character identified it in the past, but not for the other characters, multiplayer oblige, which is also irritating in solitaire,

The manual is really clear for a game that complex, though I wish (but it is probably a designer choice) a bit more clarity on how chance-to-repair, chance-to-hit, etc are calculated.

Rating : Acceptable

C. Systems

Obviously, this is where the game shines. There is so much to say, but I think my AAR covered the big picture, so here are a few clarifications on the rules :

- Characters play one after the other, but there is no “turn” for the aliens or the frenzied robots. Instead, they play during the turn of each character, which means character #1 can move and be followed by an alien, and then character #2 moves and the alien turn around and follow him or her during the same “2 minutes” (called “game time”). They also move at their own tempo – some of them are very slow and will only move every 12 seconds, others will move several times every time you take one step !

- Aliens have a great variety of behaviours. Some beeline to you to attack you, some won’t attack you until you get close, some flee, some don’t move at all, when attacked some retreat and some become aggressive – you never know what to expect and you thread carefully along aliens, until you learn to “know them”.

- A critical aspect of the boardgame I did not talk about is how instead of opening an airlock to a pod, you can “scan” it (at the cost of time units) while standing outside. Sadly, due to a bug (I will cover them later), in the computer version this only prevents you from being instakilled by vacuum.

I don’t know how much it showed in the AAR, but what really makes the game shine are the number of different ways to do one thing. For instance,

- if you want to take control of a bot, you can maybe do it by being next to a robot, or you can do it from a Dcon Pod which allows to take control of some bots remotely, or maybe you can do it using the Dcon Com, an item allowing you to take control of the Dcon Pod remotely.

- Similarly, to repair a pod you can use robots, or items, or just your intelligence.

From a few simple bricks, the game creates an awful lot of options which reward creative thinking. I found myself imagining pretty creative plans to overcome a hurdle. In one particularly satisfying instance where the first corridor of a floor was blocked by a particularly nasty alien, I explored that floor and repaired the nav pod there exclusively through remotely controlled robots that started on the other side of that alien.

As a final facet to this complexity, the time constraint stops you from preparing too much. Sure, you could spend several turns making sure your weapons, tools and robots are in green condition, but cold shutdown is just around the corner, so you explore hoping that whatever you have will work and confident that if it does not you will improvise – and again there is almost always some way to improvise something in this game.

Now, there are several bugs in the game, none of them showstoppers but three of them major :

- The most egregious one is that every time a robot is killed (whether by a player, or by an alien while controlled), the turn of the player resets to 0 and the character receives a free turn :

- When you “scan” a pod from the airlock, which should allow to safely check what’s inside, aliens and hostile robots inside the airlock will detect you and open the airlock to kill you – which means scanning pods is only useful to check for vacuum,

- Speaking of vacuum, aliens are not affected by it. It makes sense for the weird goo-ish aliens, but not for the animal-like aliens.

Rating : Very good (downgraded from excellent due to the number of bugs)

C2. Systems as a multiplayer game

Arès’ Wreck of the B.S.M. Pandora was also a multiplayer game and the computer game was also designed to be played competitive multiplayer with for instance individual scores for characters. It even increased the maximum number of characters from 5 to 7. Still, the game has some huge flaws when played multiplayer, at least in competitive mode :

- The random stats can have a huge impact on the experience, in particular speed. A “very fast” character can move at a cost as low as 3 seconds per tile – almost 4 times faster than a slow character (11 seconds per tile) who will not even be able to cross one screen each turn. The difference is acceptable when the group is united to stop the cold shutdown, but during the second half of the game when everyone is trying to earn points as fast as possible mopping aliens, the slow characters are absolutely unable to compete,

- This could be compensated by the slow characters manning the robots, but kills performed by robots don’t award any points,

- Speaking of robot killsteal, in this game you can attack other characters. Stuns on other players have no effect, but you can kill them, which makes you lose 100 points (a lot !). But if a robot you control does the deed, then as per the rule above, you don’t lose the points,

- A robot can be controlled once by “game time” ; if the first character controls a robot, then the robot is not available until the first character plays again. But if the last character controls the robot, the first character (playing again the following game time) will immediately be able to take control of the robot, interdicting it to anyone else,

- The stunned aliens follow the same rules – they recover at the end of each “game time” – therefore stuns done by the first character are useful to the team, but not those done by the last character,

Final note, though this is more an effect of the game design : some players will spend several turns in front of a pod trying to repair it (50 seconds by repair attempt), while the other players will be having fun – just ask the Data Driven Gamer.

In my opinion, this indicates almost no playtesting in multiplayer, or more likely, no time to polish the game. The consequence is a risk of mediocre and dull game experience for some players (the ones with slow characters, or the ones playing last who won’t have much access to the robot, especially if they are also slow). My recommendation : don’t play the game competitively, and if you do, end the game as soon as the ship is saved and count the points immediately.

C3. Key differences with the board game

The game is not a 1:1 port with the boardgame. The most important differences are :

- In the boardgame, there are no tiles, just pods/corridors. Crewmembers move by one pod/corridor by round, two if using a dangerous “hasty movement”. Speed is only used to determine if someone is blocked by an alien in the same pod/corridor as them,

- Aliens and frenzied robots may pick up items but not use them. I envision epic pursuits if an alien with a “flee” behaviour picks an important weapon,

- There is no “breached pod” instant death. Instead, breached pods are inaccessible without EVA suits ; breaches can be repaired,

- There are rules for movement outside the ship, with EVA suits, robots or even a small spacecraft,

- The cold shutdown timer does not start until a core pod is discovered ; overall the rules to restart the computer are more complex and more punishing.

With the exception of the removal of the movements outside the ship, I feel that the changes were beneficial to the game and properly adapted the game to the capabilities of computers.

D. Scenario design and balancing

There are only 3 options to customize the game :

- “Real-time mode” – under this mode, you lose 1 in-game (“time unit”) every real-life second. To avoid, but only because it sometimes creates issues with very fast aliens (they can attack faster than the messages for their attacks are displayed),

- Level of difficulty – commenter Porkbelly checked the code and the most obvious impact is on how much time the players have before shutdown, the formula being :

Shutdown minutes = (5 minutes x Difficulty) + (0 to 9 minutes) + (0 OR 10 minutes)

This means that at max difficulty, you could have as little as 5 minutes to save the ship – pretty much impossible. The 10 minutes toggle looks strange, until you realize you have to consider it up with the 0-9 minutes and that together it simulates the throw of a 20-faces die.

- The number of characters : in my opinion using 3 or4 creates the best solitaire experience,

In truth, the game does not need a lot of customization, each game feels very different due to the number of situations that can be created organically.

Rating : Quite good

E. Did I make interesting decisions ?

Oh yes ! Rereading my AAR I see so many things I could have done differently for instance.

F. Final rating

Good ! In single-player that’s the best game I have played so far – and I am a bit sad that the best game so far of my wargaming blog is not a wargame. At least it is SPI. It can be played by a modern player with the patience to read the manual, it will compare favourably to many modern games.

As a multiplayer experience, I would downgrade it to “Still interesting” – Galactic Gladiators is a much superior experience.

Unfortunately I could not find any real review for The Wreck of the B.S.M. Pandora – there are only a handful of mentions here and there, all very short and descriptive. The distribution must have been confidential : SPI was in no condition to pay for marketing (I could not find any ad), nor even to communicate about the game and Special Delivery Software did not address the correct audience, and itself disappeared shortly after publishing the game.

The Wreck of the B.S.M. Pandora would end up being SPI’s only computer game – I understand from Dunnigan that there were other games in the pipeline, or at least planned, but these were never released. Dunnigan left the shop in 1980 and new management was brought in, who in turn brought new investors in 1981. In 1982, the former was unable to pay back the latter and started looking for new new money. Avalon Hill refused to help at conditions agreeable to SPI, but in early March, TSR (of Dungeon & Dragons fame) accepted to lend $400 000 – provided the loan was backed by SPI’s assets : licenses, inventory, everything. Using the money from TSR, SPI immediately paid most of its other debts, including to its 1981 investors. A couple of weeks later, still in March, TSR called in the loan. SPI could not pay, and everything it owned up to that point became the property of TSR.

SPI as a brand of TSR did not survive for long. TSR refused to honour the subscription to Strategy & Tactics – it had after all only foreclosed the assets. This alienated the fans, who generally refused to buy anything from TSR from then on, including those games from the SPI-era that were ready for publication. The SPI brand immediately lost all its value and disappeared. Cynics would claim that this is exactly what TSR wanted : acquire and kill a competitor. But then everyone loved to hate TSR, and it is also possible that TSR was not aware that its loan was going to be used to immediately pay earlier loans instead of being used to turn the company around. In any case, that was the end of SPI as a computer game company. We will have a lot more Avalon Hill games to cover though, and their quality keeps rising.

For the history of SPI, I used among other sources:

- this article by SPI designer Greg Costikyan,

- this testimony by the late Redmond Simonsen,

- this blog article from Black Gate,

- this other well-researched blog article from Geekeratimedia, it uses a Fire & Movement article from June 1982 that I could not source myself

- an article titled “The Past as Future” by James F. Dunnigan in a 1988 issue of The General

- Jon Freeman’s Book of Wargames (1980)

I also had the privilege to exchange a few emails with James F. Dunnigan, though only specifically on Arès and The Wreck of the B.S.M. Pandora

As announced, I added an “Index of games by order of preference” page. The exercise of ranking all the games allowed me to realize that a few games were rated better or worse than they should have been ; consequently a handful of games received an increase or decrease in rating by one step. It will help me rate better in the future.

6 Comments

A couple of weeks later, still in March, TSR called in the loan. SPI could not pay, and everything it owned up to that point became the property of TSR.

Typical TSR evil asshole move.

TSR refused to honour the subscription to Strategy & Tactics – it had after all only foreclosed the assets. This alienated the fans, who generally refused to buy anything from TSR from then on, including those games from the SPI-era that were ready for publication.

You didn’t mention that SPI sold *lifetime* subscriptions to S&T. Naturally the attorneys at TSR refused to honor the obligation, and ruined the brand they just acquired by doing it. No matter, they were *right* and everyone else was wrong, and that was more important than money.

But then everyone loved to hate TSR, and it is also possible that TSR was not aware that its loan was going to be used to immediately pay earlier loans instead of being used to turn the company around.

Ah come on. Of course they knew. Who ever heard of giving a loan to a distressed company and then immediately calling it in? Of course they’re going to use the money. TSR doesn’t get the benefit of the doubt.

Also noteworthy is that Jim Dunnigan used computer technology to analyze user preferences and tailor his games to his audience. Every issue of S&T had mail-in postcards where users could tell SPI what games they owned and what they had played recently, and what they thought of it. Dunnigan fed these into a database and analyzed the results. A basic move, hardly worthy of mention, you say? He was doing this in the early 1970s. Wow.

One of his most surprising results was finding out that most wargamers didn’t play their wargames. They’d buy them, look at the counters, leaf through the rules, sniff the contents, and put the box on the shelf, where it stayed.

– There is a lot that I wanted to talk about that I had to cut because the article was getting reaaallly long, including the success of the “Quad game” format and the surveys in S&T. Indeed, one of those S&T surveys seem to have showed that 90% of the customers played “solitaire” (which could go anywhere from looking at the content of the box to playing alone a game designed for two players). A small note : I found that number quoted but I could not find a primary source for that. It may have been a legend because it sounds at the same time unexpected and possible.

– Again, “T$R” was not the nicest company on the market, but as I see it they loan money to SPI, and SPI use that money NOT to pay the printers that were holding SPI’s games until SPI pay, but the debtholders – said otherwise SPI did not do that one move that would allow them to continue operations and maybe repay the loan. That decision was a suicide by SPI (not that I am confident it could be saved at this point), so even a nice guy TSR would have been better off recalling the loan at this point rather than later : SPI was not going to repay in any case and the few assets held by SPI were just going to deprecate. TSR had to pay the printers after they acquired SPI, thought not at full value. Paying the debtholder first makes so little sense that I suspect that first debt was backed by the personal assets of the CEO, or something similar.

$400K to kill a company that was going to die anyway is quite the price tag.

– TSR possibly did not have that much information on SPI. The deal was negotiated in a hurry (it started to be discussed when SPI understood they would not find something acceptable with Avalon Hill) + the level of due diligence is different between “lending money” and “acquiring a company”

– I did not know that S&T had lifetime subscription. I would call having lifetime subscription a terrible business decision (cash now, liabilities forever after) and explains a lot. I understand better the risky decision by TSR to refuse to honor the S&T subscription – that’s a pricy liability to take.

“they printed 80 000 copies of a Dallas RPG. “That was about 79 999 more than anyone wanted“, quipped Simonsen.

couldn’t resist googling that one – and it delivered.

Another little bug is that you can take off your vacuum rig while inside a depressurised pod, and you won’t die.

“interdicting it from the first player” > I think you meant last player, here.

FYI, it was the venture capital firm who had loaned SPI money that initiated the squeeze play; the TSR “loan” was negotiated between TSR and them with the explicit objectives of getting their principal back with interest (venture capital firm) and acquiring all SPI assets (TSR).

TSR also indicated an interest in retaining the design staff, but by the time the transaction went down, most of them had accepted an offer from AH to be set up as a separate design studio (Victory Games) and TSR did not make a serious counteroffer. A couple of weeks after the deal went down, the fired one of the two they did retain (Redmond Simonsen) and the other immediately quit (yours truly).

First, thanks a lot for coming here, and thanks a lot for the clarification. I stand corrected ! It is great to have testimonies from people who were there in those events that happened some 40 years ago.

Do you know remember why the computer game Wreck of the BSM Pandora was published by Apple Special Delivery Software ? One of the hypothesis I had after writing the article was that it was done by TSR which did not know what to do with the almost complete game, and did not want to have it published by anyone that could become a competitor, eg anyone publishing games.