The good thing with the Japanese Navy not being totally forthcoming about the result of the battle is that we have cool paintings for our AARs

After my glorious victory at the Battle of the Coral Sea, I move to the Queen of the Pacific War battles: the Battle of Midway. Once again, I’ll use the rare opportunity I am given to play the Japanese to actually play the Japanese, even though all odds are stacked in their favour, so I don’t see how the Americans can prevail.

This time, I am given the largest fleet I have ever commanded on this with no fewer than 6 aircraft carriers and so many battleships and cruisers that I can’t even be bothered to check their names. My objective is to land my invasion force on Midway and ideally sink the 3 American carriers: the USS Enterprise, the USS Hornet and the USS Yorktown, the latter technically I have already sunk in the Coral Sea, but since historically she was only damaged and repaired in emergency, she is back in this battle.

Order of battle

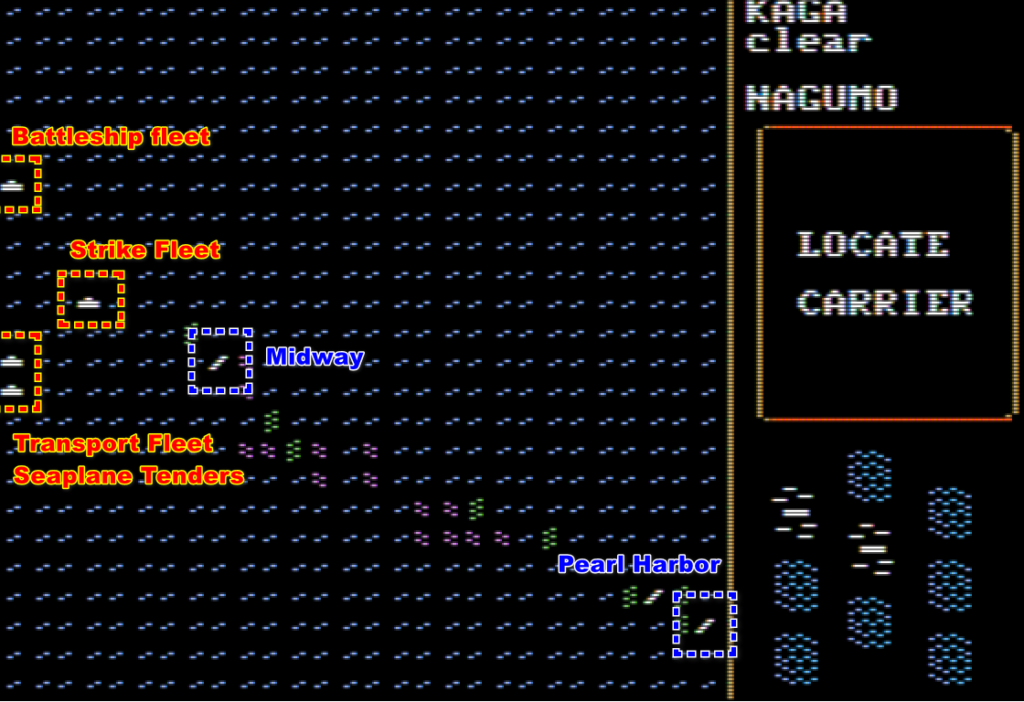

The battle starts the night of the 3rd of June with 4 “Commands” under my order:

- The most important group is Nagumo’s Strike Fleet, as it includes 4 Japanese fleet carriers: the Akagi, the Hiryū, the Kaga and the Sōryū – more than 250 planes between them. Nagumo also controls a group of destroyers (they will escort the Strike Fleet for the entire battle) and a small battlecruiser force,

- Yamamoto has taken personal command of the Battleship Fleet, which includes among others the famed Yamato. The very light carrier Hōshō tags along – it only carries 8 bombers so it is unlikely to make a huge difference.

- Kurito controls the transport fleet and two seaplane tenders: the Chitose and the Kamikawa Maru,

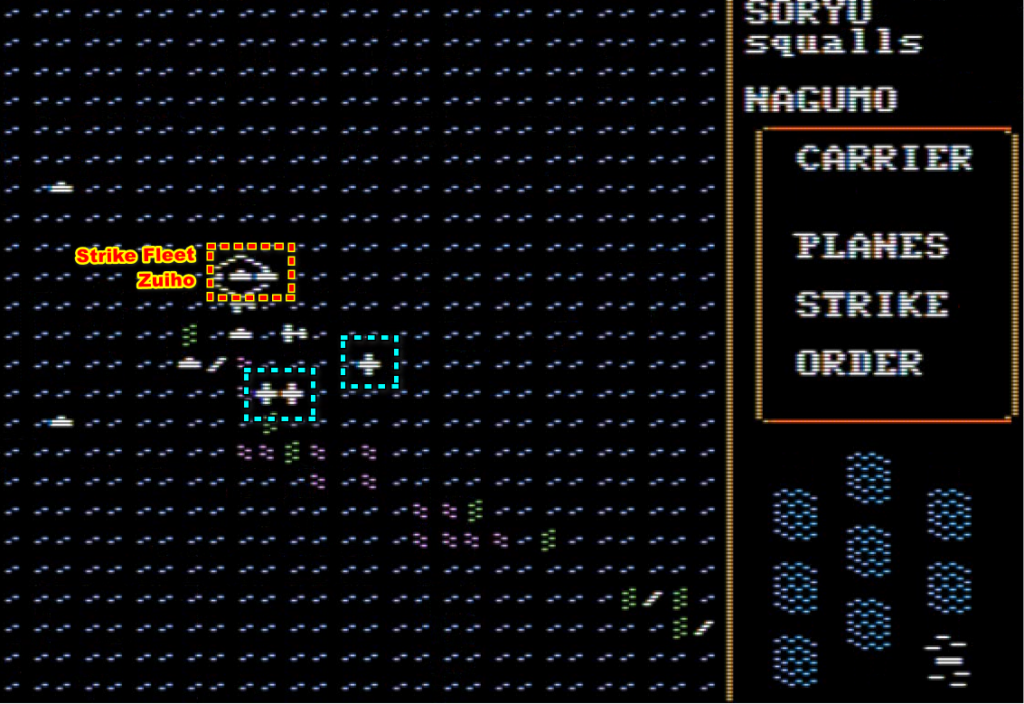

- Finally, Kondo controls the battlecruiser fleet – currently escorting the transport fleet. His best asset however is the light carrier Zuihō, which carries 12 fighters and 12 bombers.

I don’t like the idea of having my various fleets & carriers spread out, and I would prefer all my warships aligned in a horizontal line West of Midway. For this reason, I order the battleship fleet and the Hōshō to head South (thereby cancelling their “bombard Midway” order). Meanwhile, the strike fleet will keep Midway at the extreme limit of the range of its bombers, and the Zuihō will move slightly East to the planned position of the strike fleet. Ideally, I will neutralize Midway before they can send any plane in my direction, but if they do, hopefully those bombers will find the Zuihō and not push any further West.

Finally, before starting the game, I order the two seaplane tenders to find a place to anchor so they can launch their planes. I don’t know it yet, but I could just as well have ordered the captain and all the crew to scuttle their ships then and there.

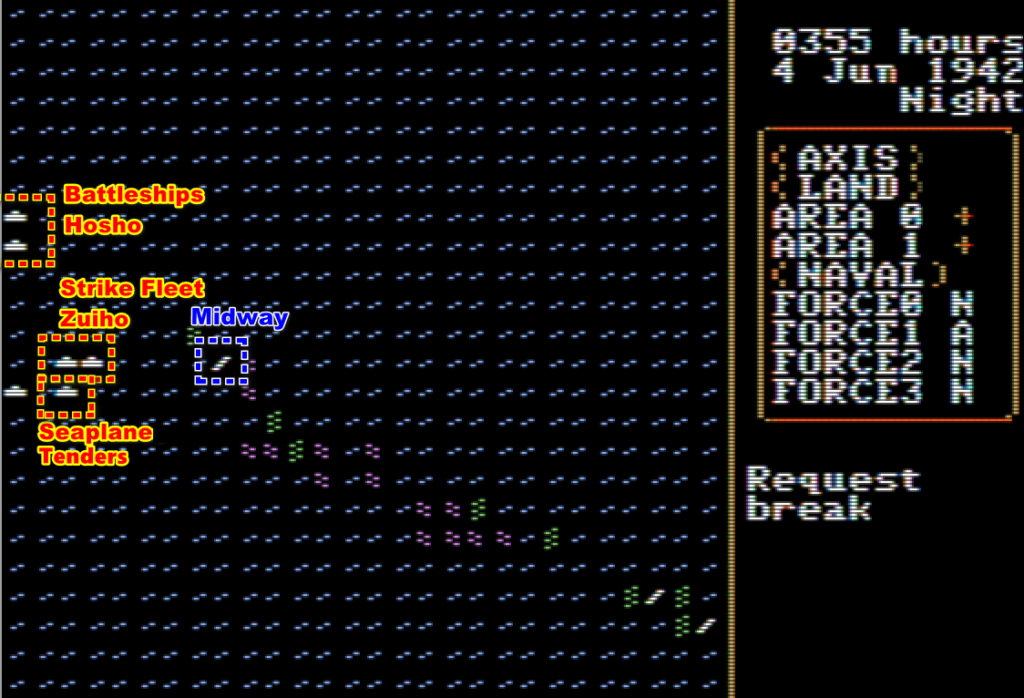

4th of June

The Strike fleet and the Zuihō have reached their position on the morning of the 4th, and I move my Val dive bombers on deck, along with some escort, at 4 in the morning. I prefer to keep my Kate torpedo bombers in reserve in case I detect an American fleet in the morning. At 6, I launch the planes!

The initial reports claim only light damage caused to the Americans, so I prepare my planes for a second attack. I also order the two battlecruiser fleets to beeline for Midway for close-range shelling. My planes take off again at 11:30, and on their way to Midway they cross American planes (SB2U Vindicator) going in the other direction. Around this time, I also detect an enemy fleet East of Midway.

The enemy fleet is out of range, and I can’t move my carrier because it is waiting for its planes to return. On the other hand, I am out of their range, so my fleets are only attacked by Midway-based planes. These spot my battlecruisers, damage the Kongō and the Hiei somewhat and return back to their base without investigating where all those Japanese planes came from.

When my planes return, I don’t send a third strike. Midway can wait: my report states that 25 US fighters and 25 US bombers were destroyed and even if this report is exaggerated, there are probably a good number of damaged planes. With Midway now either neutralized or quelled, I am now worried about the American fleet, particularly the ones I don’t see. I clear my deck and sail West at flank speed until the night protects me. I expect my surface fleet to make short work of whatever is still standing on Midway during the night, allowing me to focus exclusively on the carriers tomorrow.

5th of June

I have the most difficult awakening in my life since that sake crawl in Osaka. Absolutely nothing is going well!

- My battleships, battlecruisers, cruisers et alii reached Midway… and did not attack it. They never will. You see, you need a “bombard” order to bombard Midway, and bombard orders can only be given by the designer at the start of the scenario. If you cancel the order, for instance because you want to move your fleet freely, then you can never return to that order. My ships in front of Midway are now useless, except as part of an epic background scenery for the Marines. I imagine the captain of the Yamato staring at his giant guns, then staring at the puny planes on the tiny island, and then answering to the Admiral: “I am sorry, Excellency, but without a new sealed envelope given to me while we’re ashore, I cannot do anything“.

- The two seaplane tenders, who were given two days earlier the order to anchor somewhere to send their scout planes, have still not stopped. They are heading towards Pearl Harbor and clearly they want to anchor there. I don’t stop them, I have some hope they stop before that, and they are useless if they can’t send their seaplanes anyway,

- Finally, some American bombers found the Hōshō and disabled her, and I could not stop the game in time to see whether the bombers were ground-based or sea-based.

The rest of the day is frustrating. The American carriers are somewhere, so I am worried about sending a third wave toward Midway and finding myself naked if the American carriers chime in. Ultimately, I send a modest couple of squadrons of Val dive bombers. I don’t know if whoever attacked the Hōshō came from Midway, but if they did then my last raid did the trick and I don’t spot any new American planes in the area. At 13:00, I split the Zuihō from the rest of the carriers to scout a larger area, to no avail.

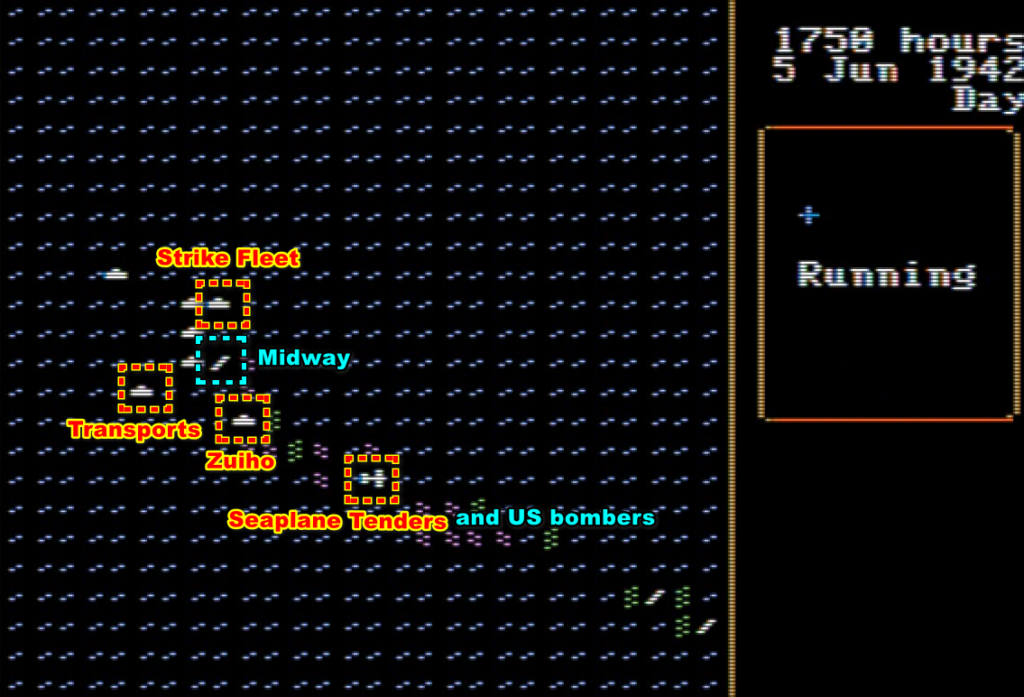

Meanwhile, the American carriers, presumably further East and South than where I was looking for them, sink my defenceless seaplane tenders. To avoid sharing their fate, the Zuihō is ordered to return with the Strike Fleet

This concludes the day. Objectively, I did not lose much: the seaplane tenders were useless and Hōshō, which eventually sank during the night, only added marginal capacities to the rest of my fleet. Still, that was frustrating.

6th of June

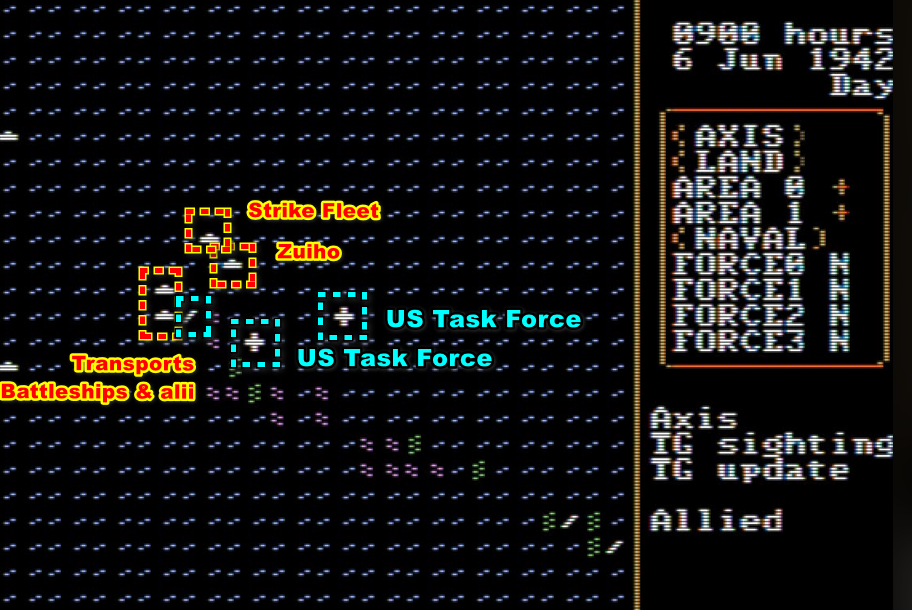

This is the last day. At 9:00, just as I was wondering whether I should strike Midway one more time to be on the safe side, two American task forces are spotted!

The situation could not be more perfect. The “Western” US fleet is, compared to the Strike Fleet, at the limit of the range of the Japanese planes – which means it is out of range of the American planes. The “Eastern” US fleet is, similarly, at the limit of the range of the planes on the Zuihō – which means again the Eastern US fleet can’t reach the Japanese carriers. Of course, the Zuihō is within range of the “Western” US fleet, but you can’t have everything.

This is the final moment of the game. All my planes were on deck except for the ones of the Akagi (I wanted to test whether a clear deck helps with sending scouts – and maybe it did). I immediately send all of them on two strike missions: the planes from the Strike Force will attack the” Western” fleet, and those from the Zuihō will go after the “Eastern” Fleet.

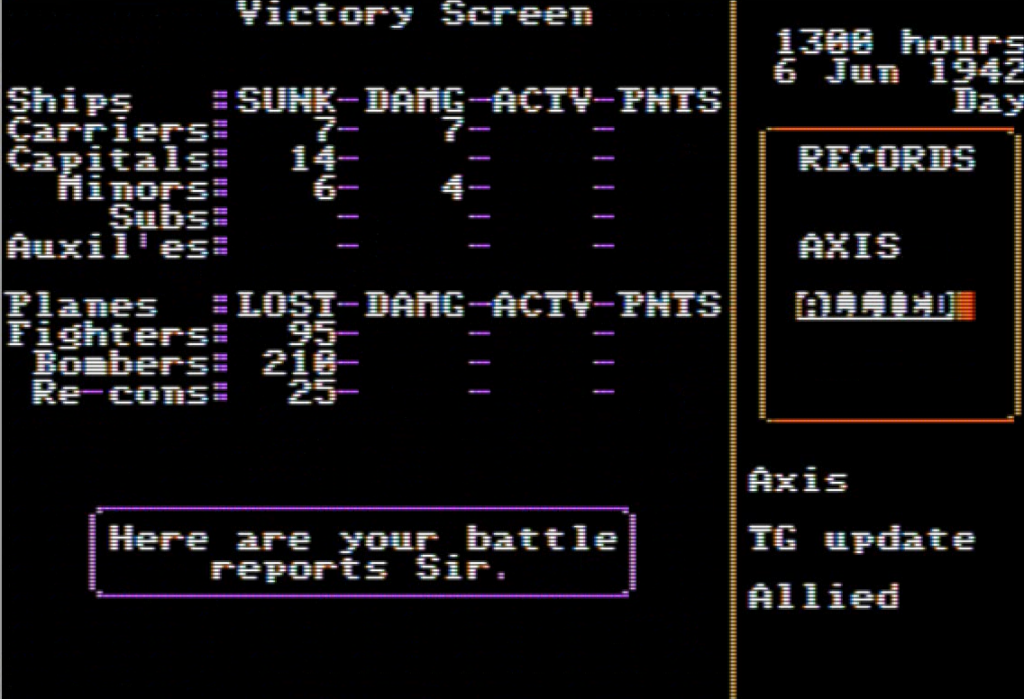

Starting at around 11:00, the planes from the Strike Fleet hit repeatedly the “Western fleet” – and keep in mind that there are around 250 of them. Meanwhile, the 12 Val from the Zuihō manage to attack the “Eastern” Fleet. Unfortunately, the Zuihō is herself under attack by American planes. Badly damaged, she is out of action, and will sink a few hours later. Nonetheless, the attack is a decisive success, with my pilots reporting the destruction of 7 American carriers and 14 other capital ships! I apparently damaged 7 extra carriers on top of that.

At 13:00, most of my planes have returned, and I launch a second strike, splitting my forces between an American fleet I already attacked and a newly spotted one next to it.

The final wave is delayed a bit by a bout of squall, but when it leaves the carriers at around 16:00 it does not miss its targets:

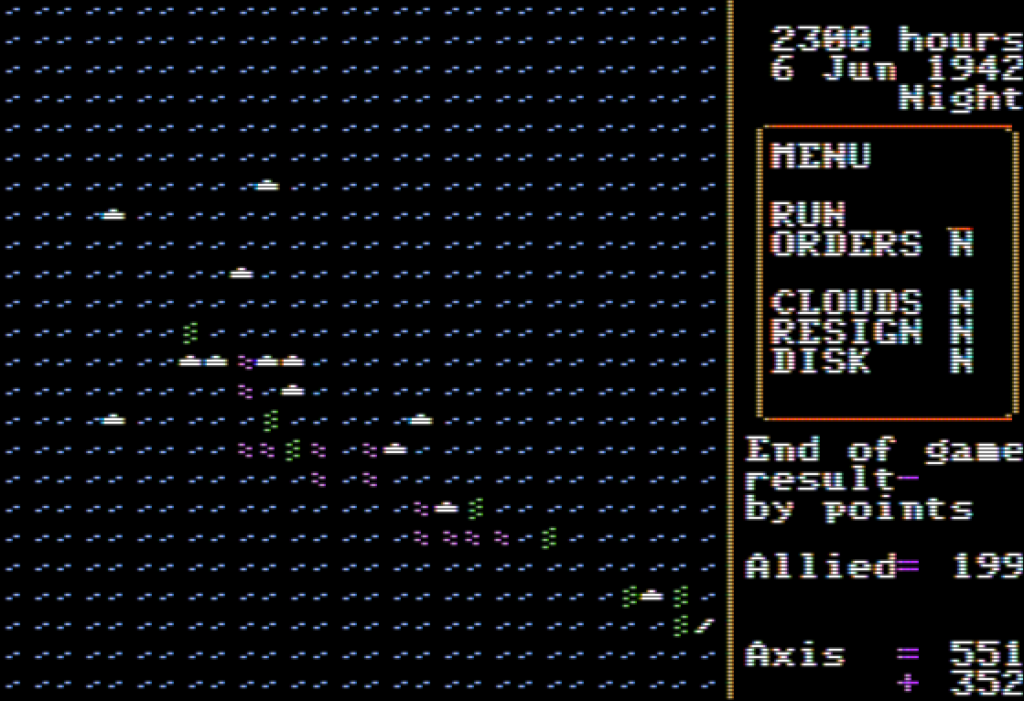

That’s the last attack. While those events unfolded, my troops disembarked at Midway, earning me a total victory.

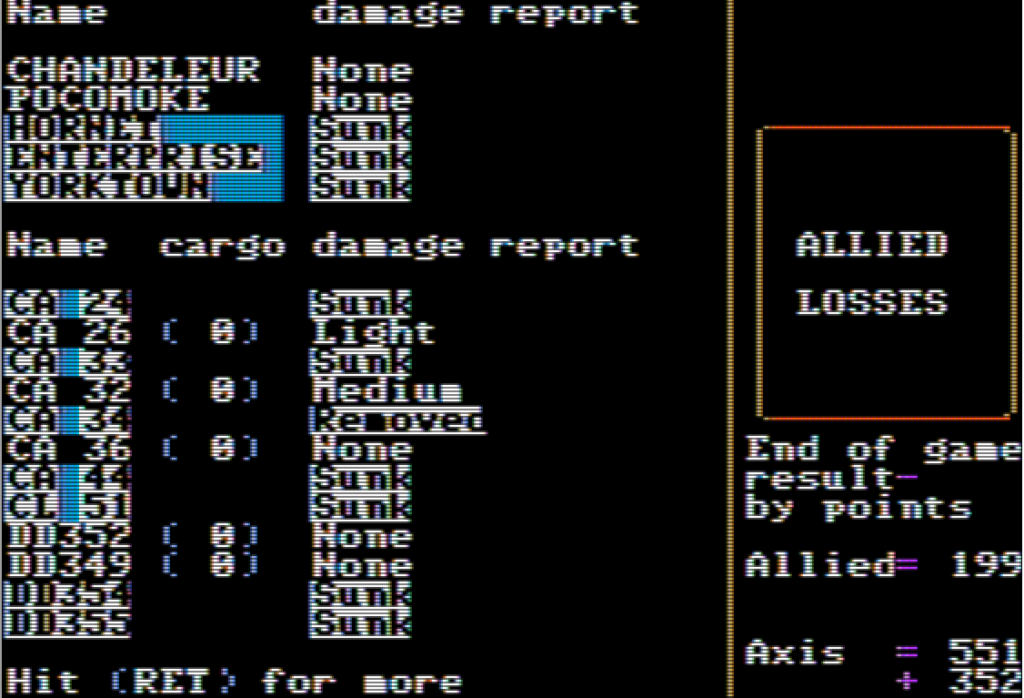

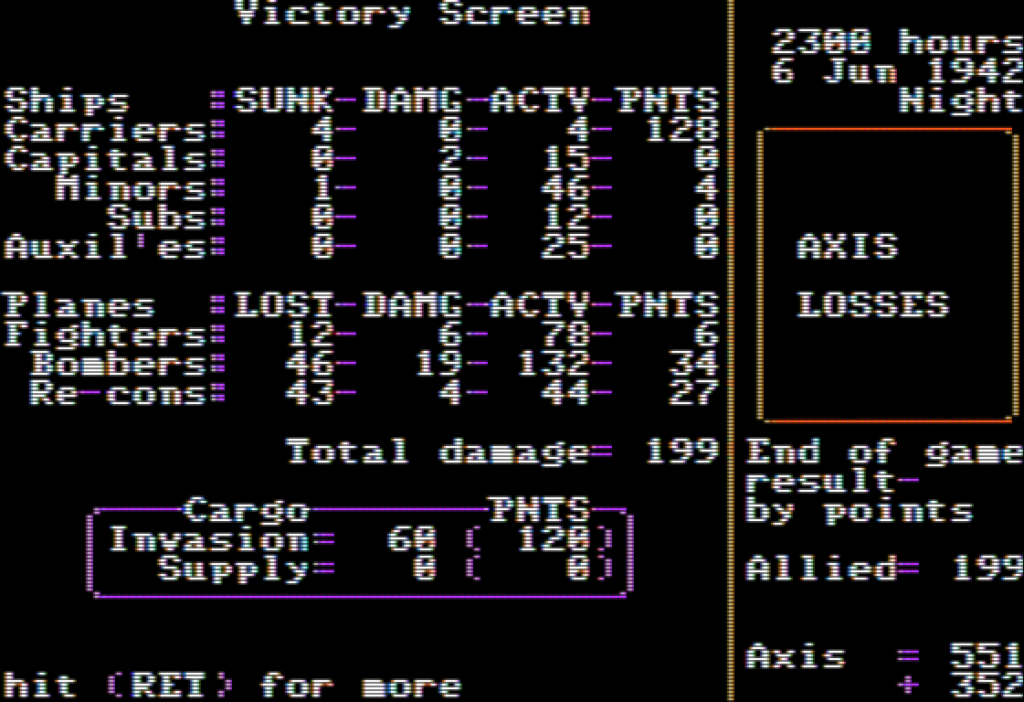

Checking the final status of the battle from the US point of view, the victory is decisive indeed as the Americans lost all their aircraft carriers, 330 planes and a good number of their cruisers. After such a defeat, I don’t see how the Americans could play a meaningful role in the Pacific before late 1943 at the very least – Australia is back on the menu.

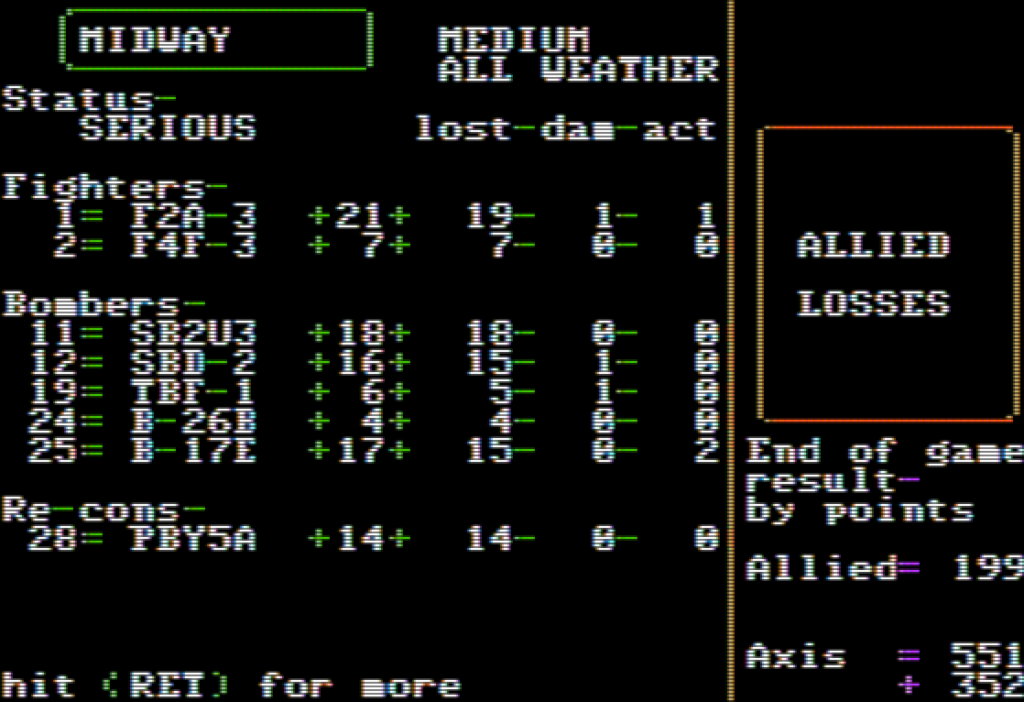

As for Midway – probably Japanese at this point – it had been thoroughly neutralized:

Finally, on my side, the losses are limited: two seaplane tenders, my two smallest carriers and one destroyer:

I made a lot of blunders in that campaign, but none of them mattered because it all came down to finding the Americans before they found me and attacking them before they could get in range. While I did like this session, the various design issues I encountered make me think of the game a bit less highly than I did after the battle of the Coral Sea – but it’s still a great experience. For the next article, I will stop playing in easy mode. I’ll take the numerically inferior Japanese in the battle of the Eastern Solomons, before swapping and playing the numerically inferior Americans in the battle of Santa Cruz.