[Apple II, Speakeasy Software]

More than two years ago, Renga-in-Blue brought my attention to an early computer wargame: Warlords. I added its existence to my list, but skipped it: it was multiplayer only and hard to emulate. Earlier in 2025 however, I coerced convinced a team of volunteers to join me and backtracked to this early wargame.

And so, we started a 4-players PBEM campaign of Warlords, with myself, veteran commenter (and several times winner of multiplayer games) Dayyalu, commenter Rastignak and finally Morpheus Kitami from Almost a Famine. A word of warning: Warlords is above all a number game, so this is going to be about as engaging as an AAR in algebraic notation.

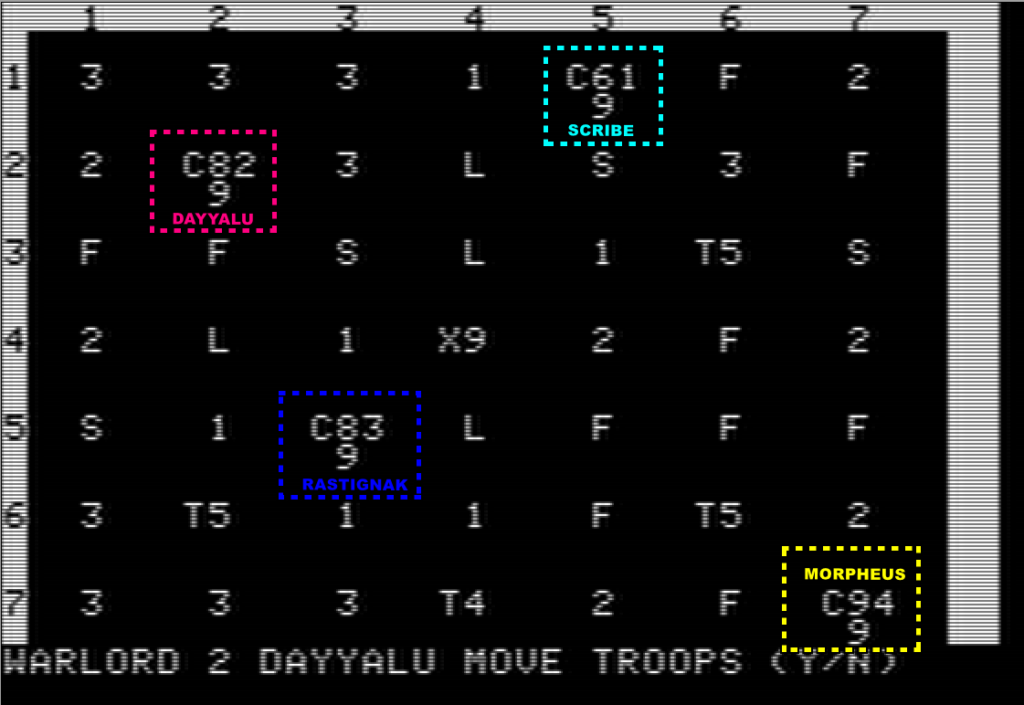

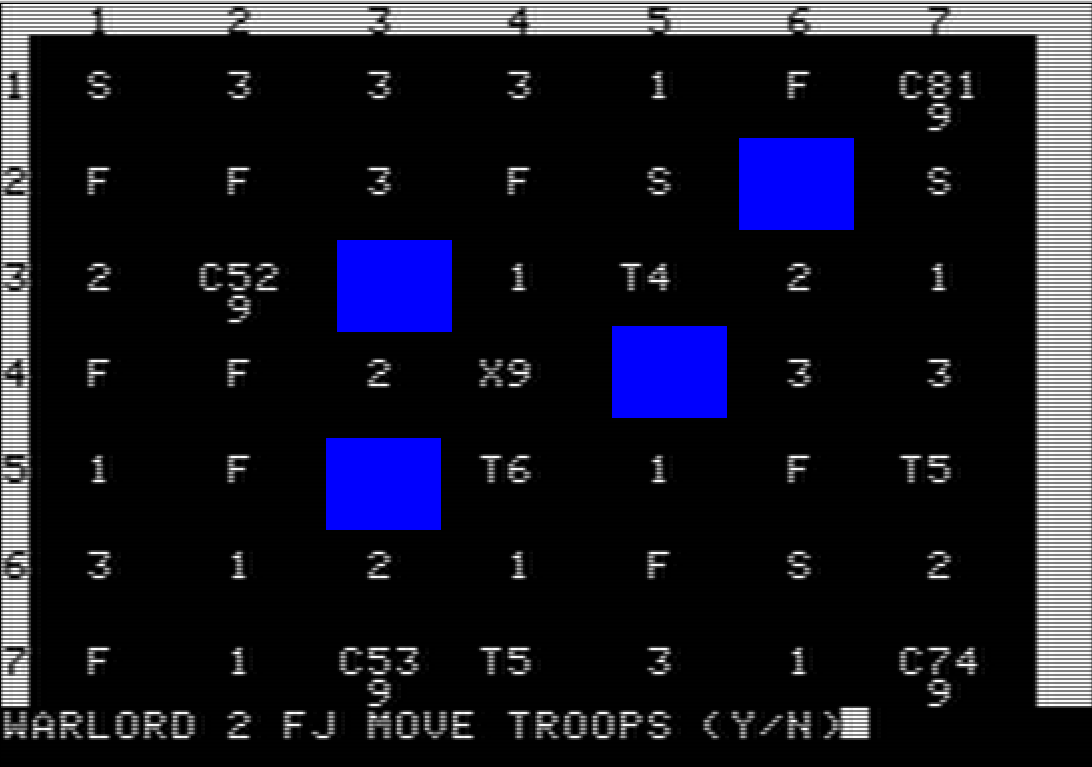

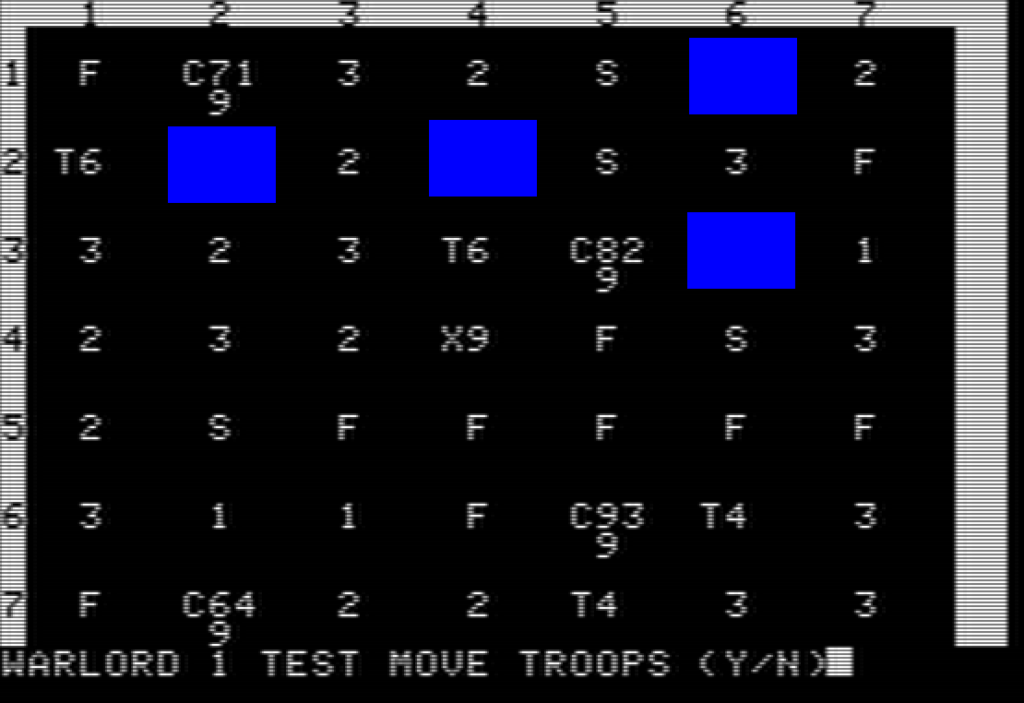

The game is played on a 7×7 map, with up to 4 characters on each tile, in the following order:

- The nature of the terrain: F(orest), S(wamp), T(own), C(astle), L(ake) and what we quickly dubbed the Xity in the centre of the map, even though the game calls it the “Capital”. Terrains without letters are open. Lakes are impassable.

- The revenue it brings every turn, between 0 (for forest and swamps, which are defensive terrain) and 9 for the Xity and Morpheus’ castle.

- The owner, if any: Myself (1), Dayyalu (2), Rastignak (3) or Morpheus (4),

- Finally, the size of the garrison as a number below the 3 other characters.

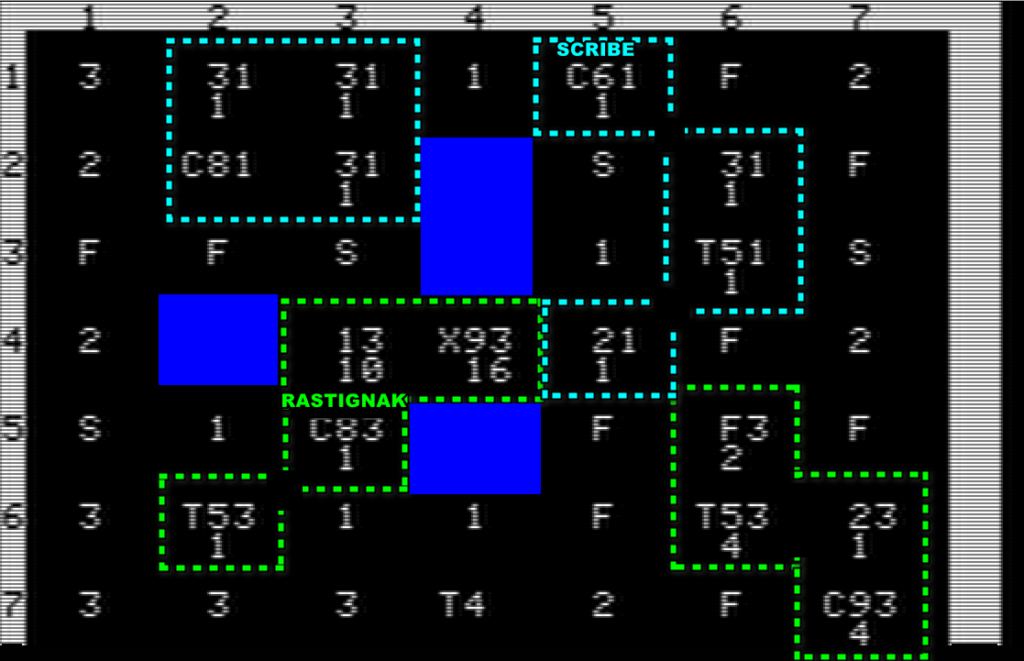

Turn 1

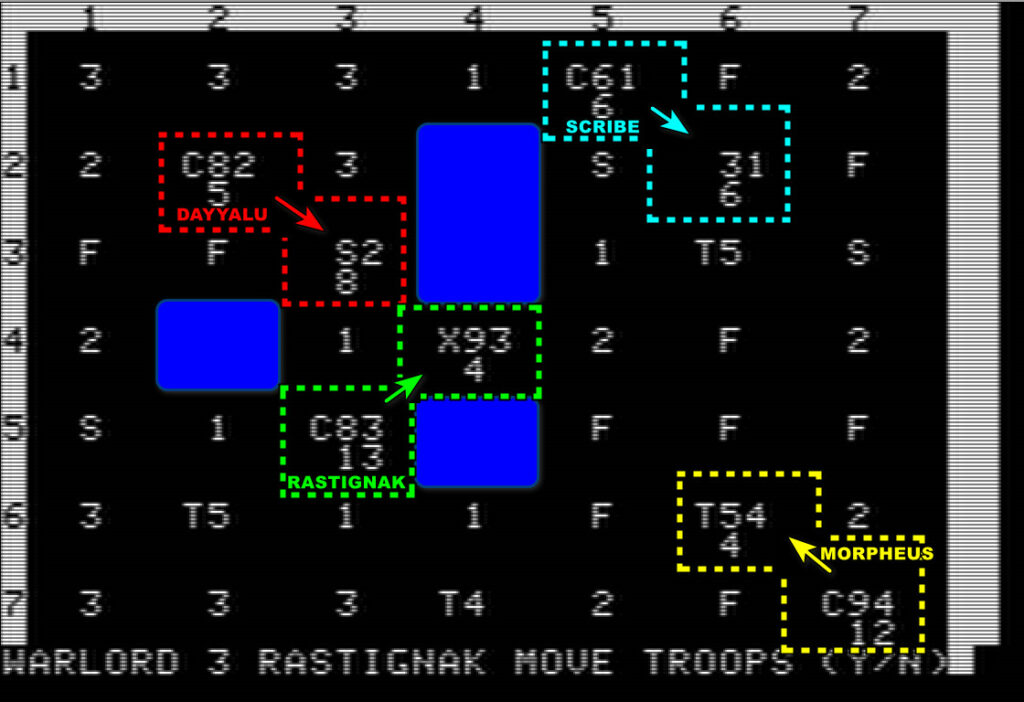

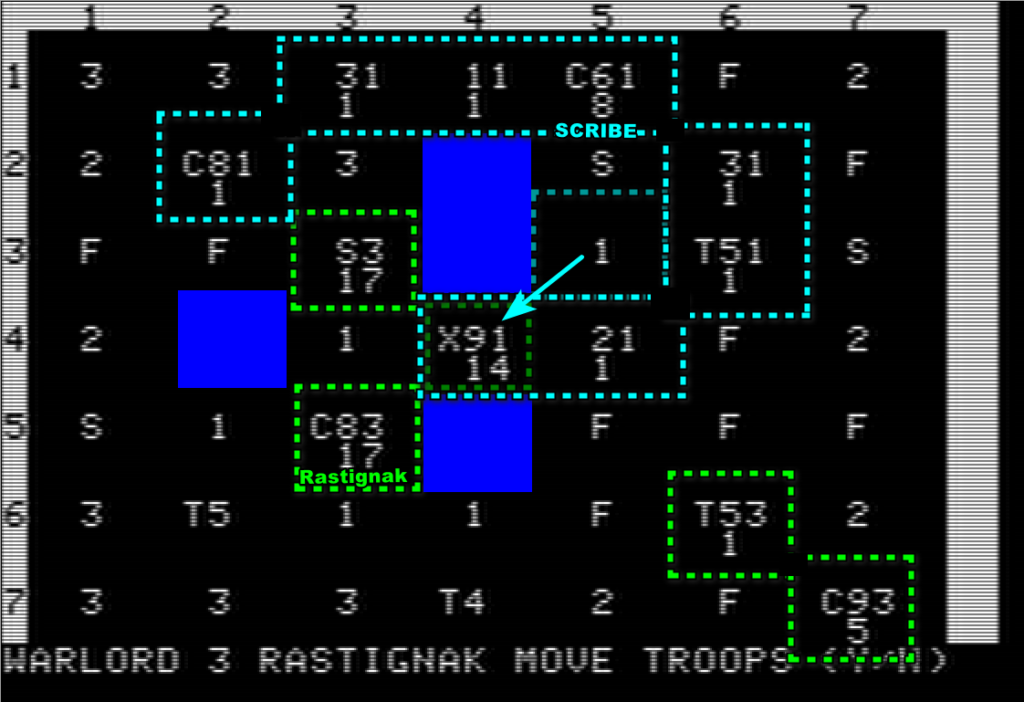

Each turn is played as a succession of “impulses”, during which each player gets to move once. Both the number of impulses in any given turn and the order of play within an impulse are random, so players can sometimes play twice in a row (end of one impulse, start of the following one). The first turn happens to have only one impulse. This allows Rastignak to seize the Xity next to his castle without having to defend it against Dayyalu, who also tried to rush the Xity but ends up in control of a pointless swamp. Meanwhile, I am not doing so well as my castle is the poorest of them all and I can’t even rush the town in the South-East. Morpheus fares better in his isolated corner of the map.

Turn 2

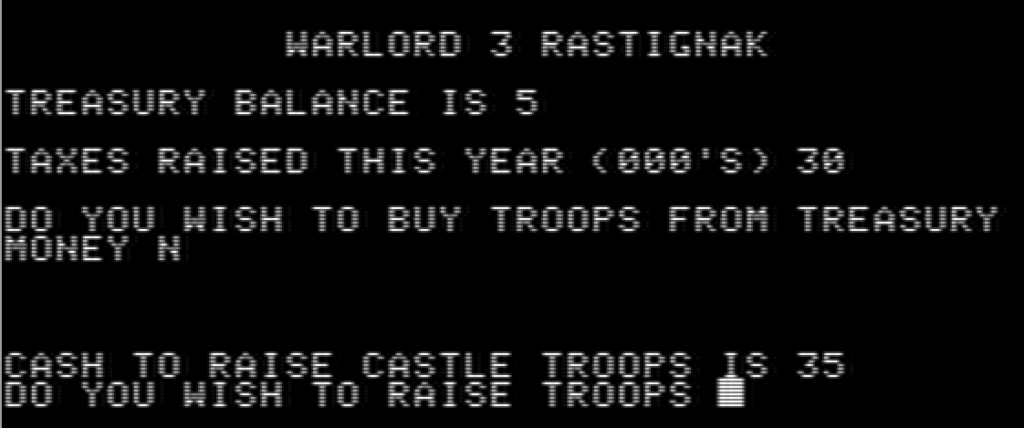

At the end of each turn, players can buy new armies. A point of strength costs 2, with a choice between

- spending the revenue immediately (in which case the armies are recruited in the castle)

- spending later, in which case the future armies can be recruited in any controlled non-Castle non-Xity location.

It is possible to build both in the castle (using the last turn’s revenue) and away from it (using revenue from a previous turn), but a player can only build in one “away” location by turn.

Rastignak has a revenue of 17, against only 8 for Dayyalu and 9 for me. I keep some savings for later, but Rastignak goes all-in, and with his superior army assaults Dayyalu. Dayyalu’s army of 8 is crushed by Rastignak’s army of 9 despite occupying a swamp that theoretically gives a strong defensive bonus. Rastignak only loses 2 strength points!

Dayyalu would have had, maybe, a chance if the turn had ended there, but it did not. The following impulse, Rastignak seizes Dayyalu’s castle, effectively removing him from the game!

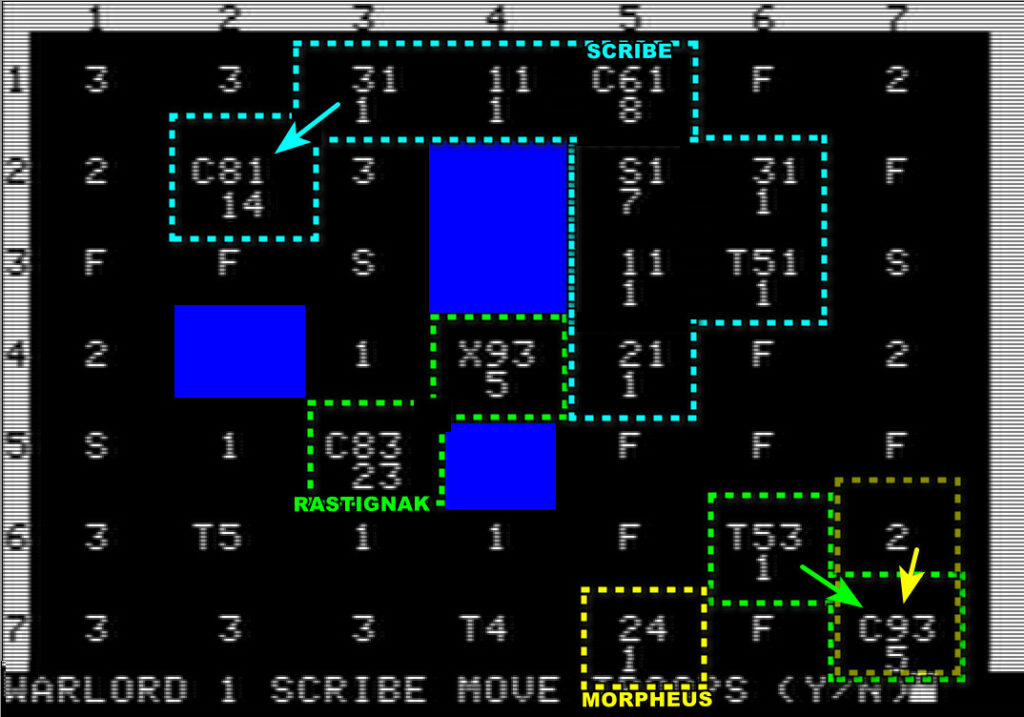

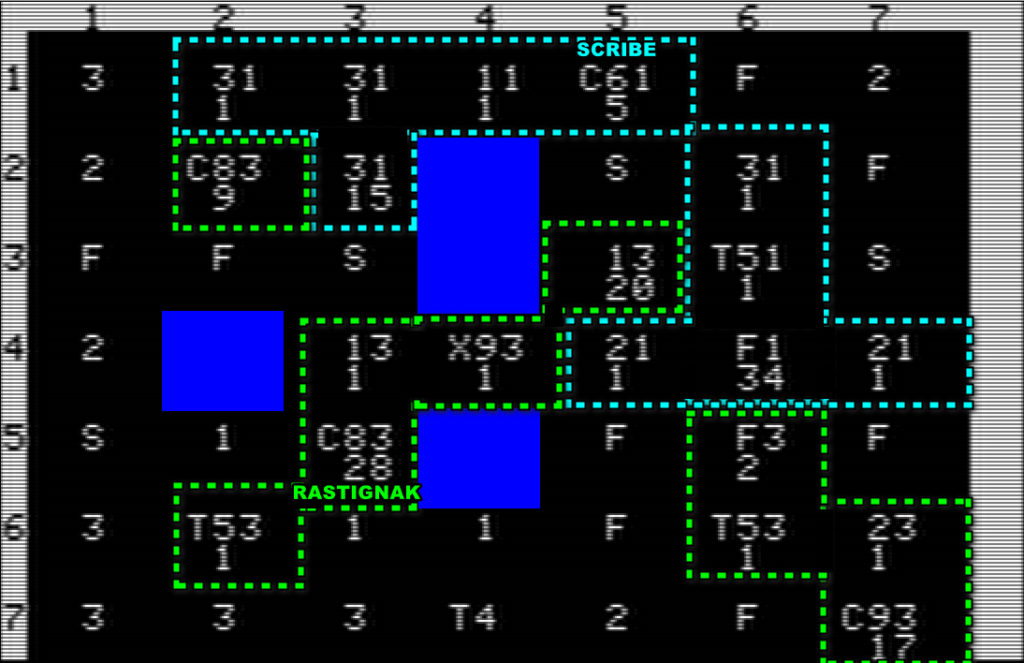

Turn 3-4

Rastignak now has an immense advantage in revenue: 25 vs less than 20 for both Morpheus and myself. We immediately ally, and I mass a decent force next to the Xity. Unfortunately, Rastignak has a much larger force in his castle, ready to retake it. I don’t have a good opportunity to attack, or if I do I squander it.

Meanwhile, Rastignak goes all-in against Morpheus, even taking the town next to the latter’s castle turn 3. However, unlike Dayyalu, Morpheus managed to muster a significant force and pushes Rastignak back turn 4 while sending me various pleading emails about doing something, anything, to support him. I did not quite deliver, but by then I had come to realize that the best course of action is to take Dayyalu’s former castle – Rastignak after all won’t be able to defend everything.

Turn 5-6

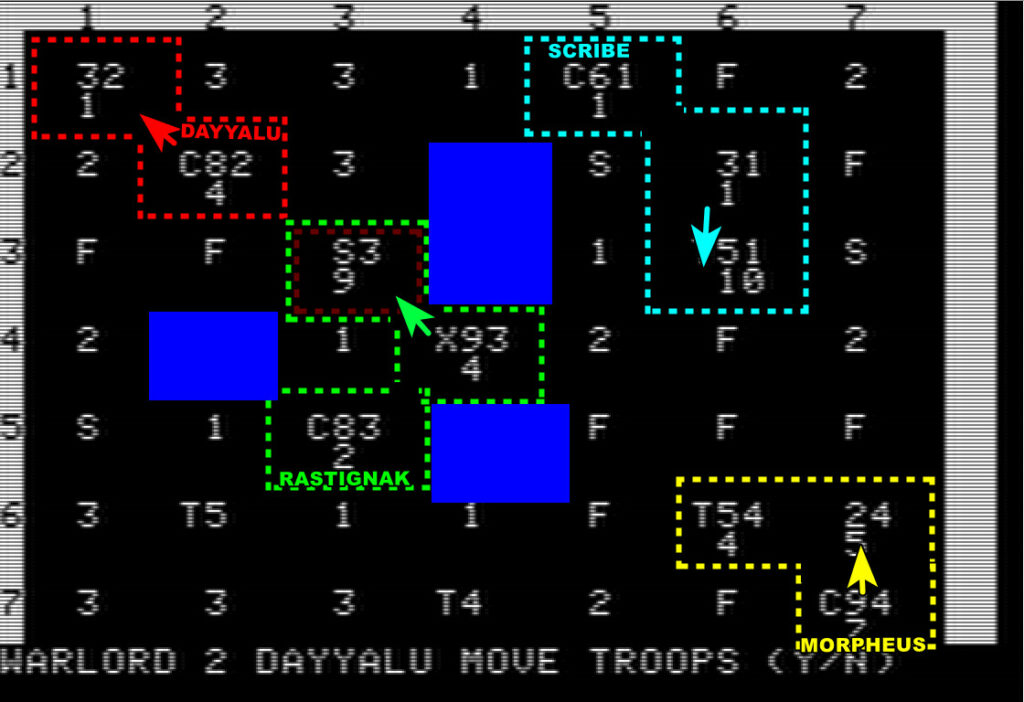

Turn 5 happens to be a one-impulse turn, much to the frustration of Morpheus and myself:

- My Northern army stops right in front of a castle that Rastignak will be able to reinforce,

- Morpheus loses a town and does not get a chance to retake it before Rastignak gets to reinforce it.

However, Rastignak can only reinforce one location at the end of the turn. He chooses to reinforce the South-Eastern town to finish off Morpheus – allowing me to take Dayyalu’s castle at the cost of 8 units against only 3.

The turn, however, does not end after one impulse. I approach the Xity from the North-West, but Rastignak crushes my force of 13 with a force of 18, losing only a few soldiers. Once again, the swamp did not protect the defender much.

Happily for me, that’s where the turn ends – before Rastignak can waltz into Dayyalu’s former castle.

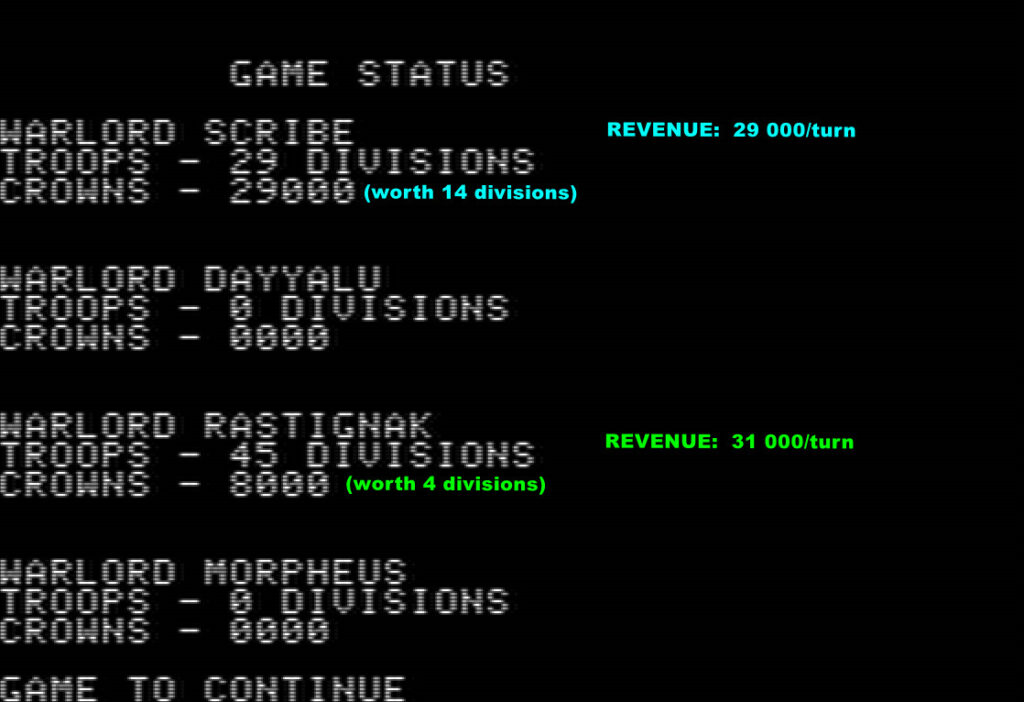

In this final duel, I am almost on par economically with Rastignak, though my number of troops is much smaller. I may be able to win this.

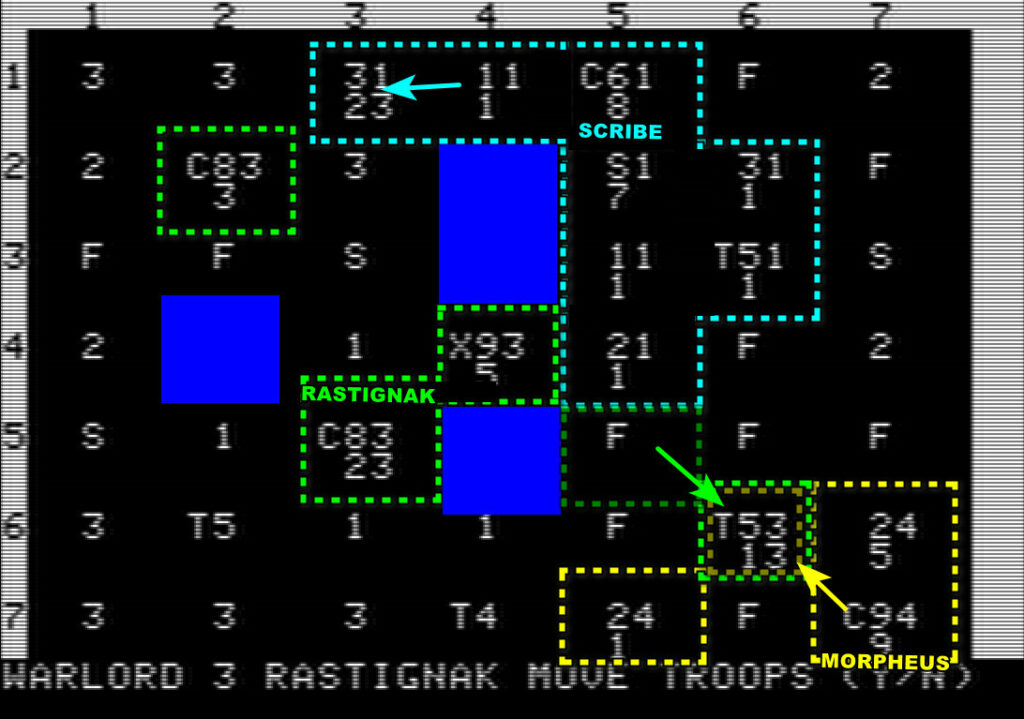

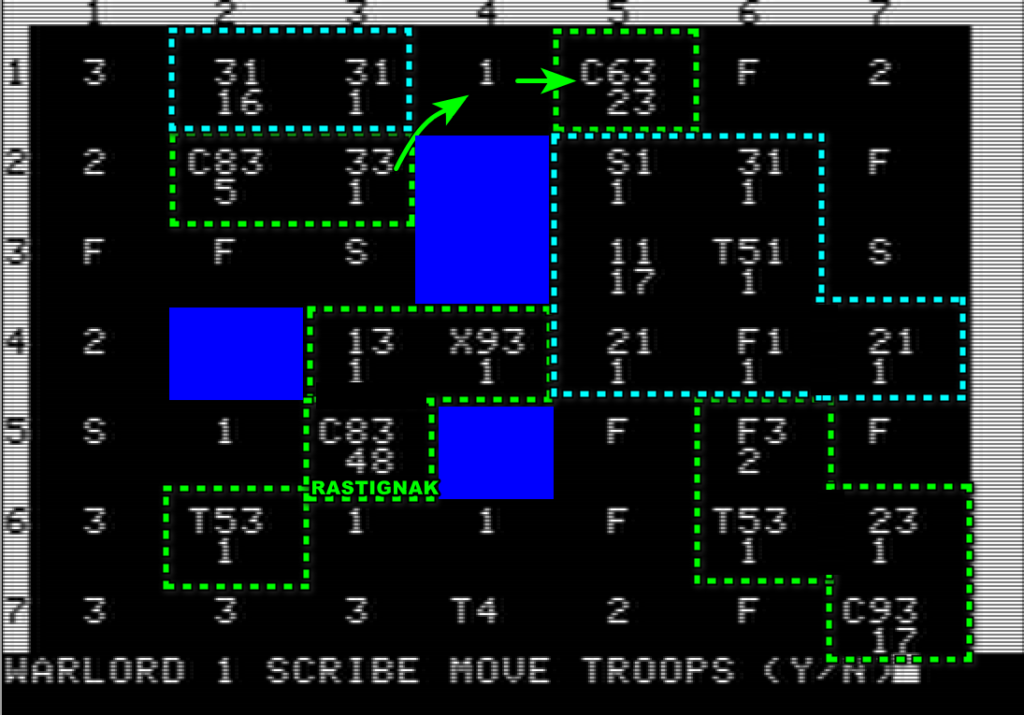

Turn 7

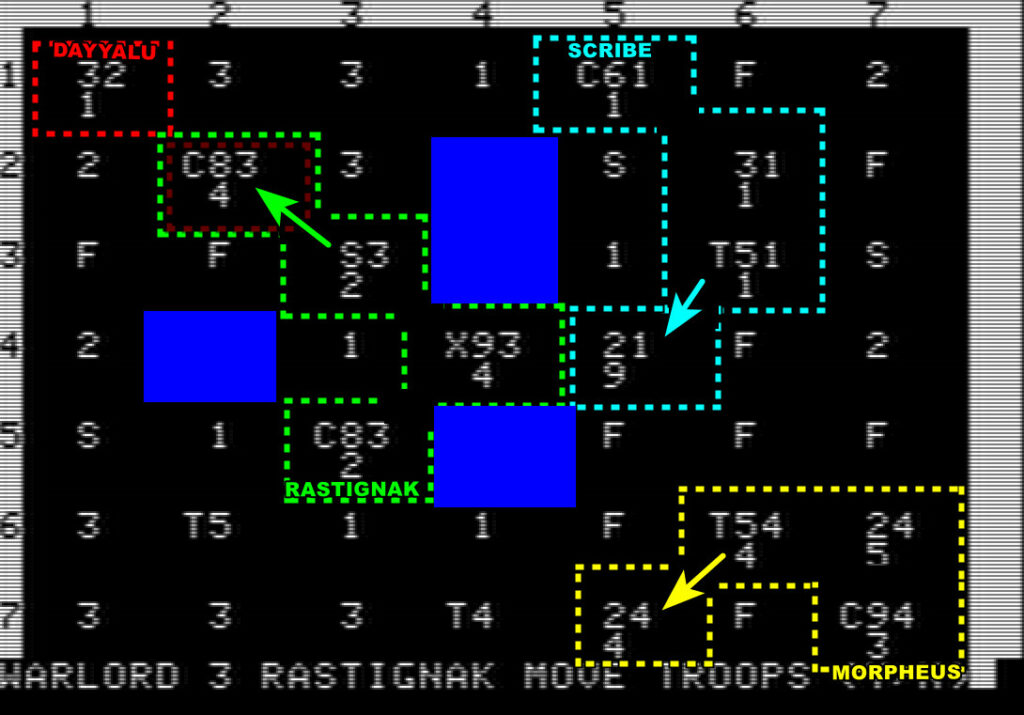

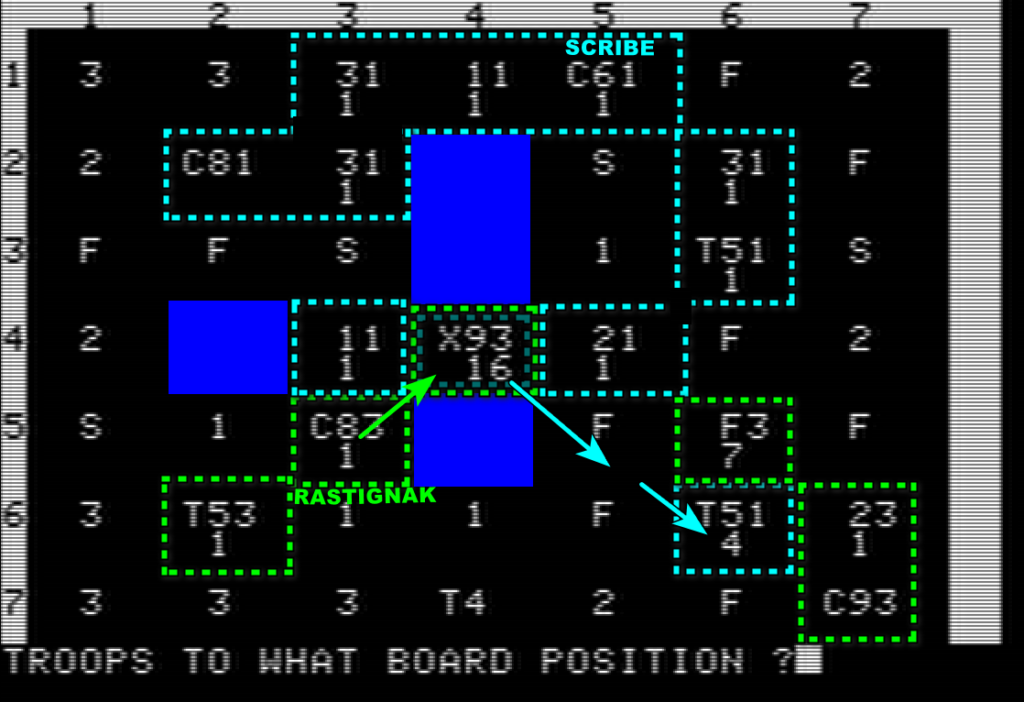

I move first turn 7, and since I could recruit some forces next to the Xity I take it easily.

Rastignak retakes it, of course, but it costs him the 17 strength points near Dayyalu’s castle and then 5 more strength points from his own castle. This means I’ve largely bridged the power gap.

- I have 16 troops, whereas Rastignak has 18, so his +16 advantage “on the field” turns into a +4 advantage,

- However, I need to act fast! Rastignak took a town and a plain, and his revenue is now 38 vs 31 for mine, so +7 in his favour (worth 3.5 armies/turn),

- Finally, I have 14 units “waiting” every turn that I don’t want to deploy in my castle, so I always need to wait one more turn to bring them directly to the front;

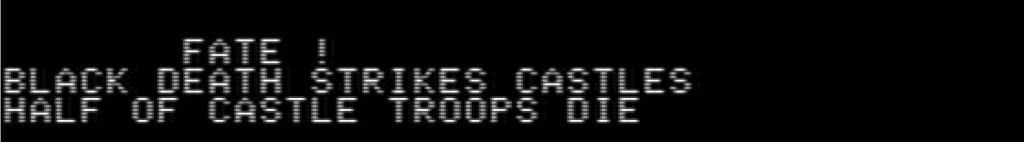

I need an extra nudge, and fate gives it to me:

This could not have happened at a better moment, because Rastignak loses half of his new recruits, giving me a decisive advantage near the Xity. It is my game to lose.

Turn 8

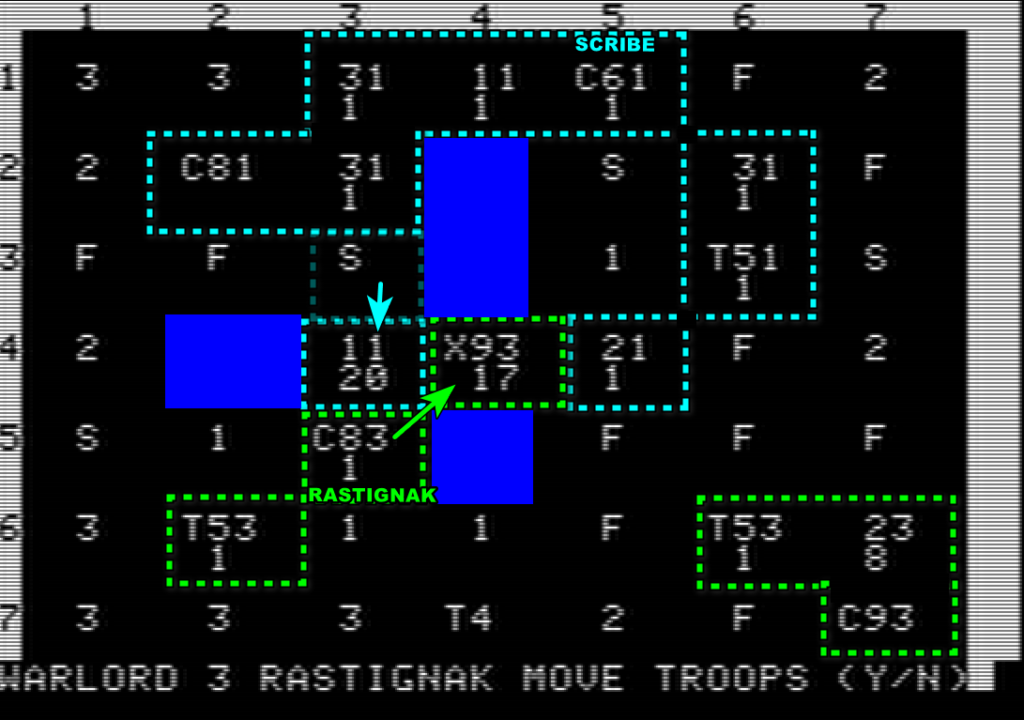

Rastignak moves first, and puts all his troops into the Xity. I immediately fork them with the castle.

Of course, I immediately move toward the castle. Rastignak is forced to garrison it, and I take the Xity.

Neat, but the turn continues. Rastignak brings troops from the South-Eastern corner, which is both a risk and an opportunity.

- A risk, because my castle is defenceless, so he can approach it and force me to reinforce my castle, which would allow him to retake the Xity next turn with forces levied in his own castle.

- An opportunity, because the South-Eastern corner is undefended.

At this point in the game, I had misunderstood how battles were resolved and based on the experience of the previous turn (where a garrison of 13 killed an army of 17 with minimal losses, then killed more soldiers of a second attack of 17 men), I reckoned that I could probably detach a few men from my garrison to beeline to Morpheus’ former castle in the South-East…

… and Rastignak retakes the city with only 1 loss!

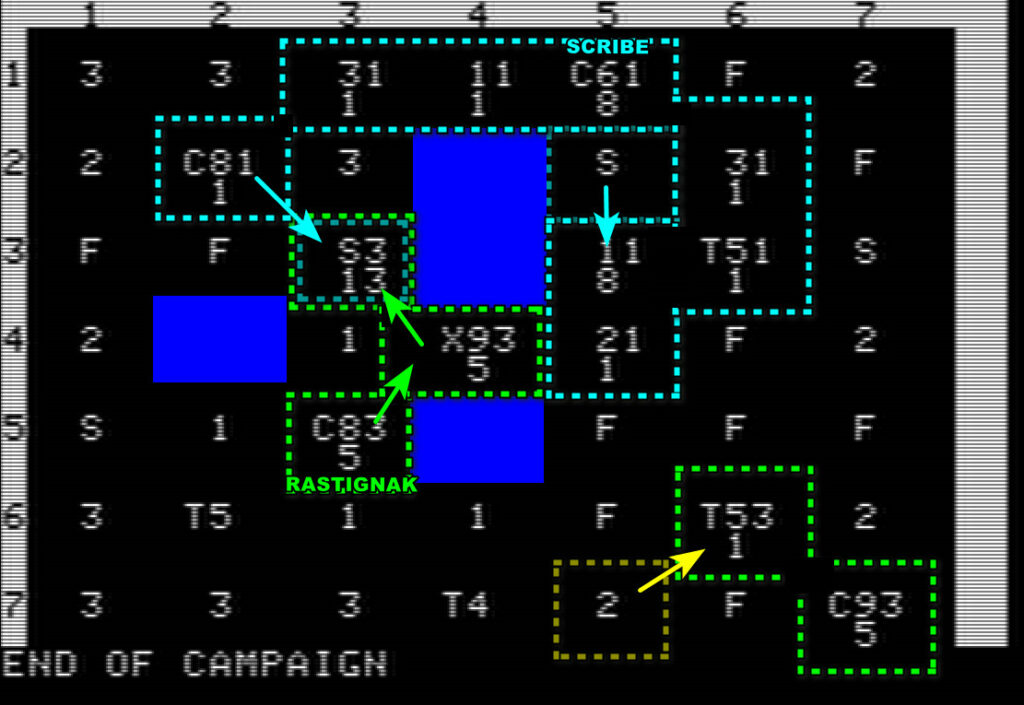

Turn 9-15

Turn 8 was my high ebb; I went down fighting but never came that close to victory. I also showed all there was to see about this game so let’s run quickly through the remaining turns.

I create an army between Rastignak’s castle and the Xity with the objective of both pinning his armies and take the South-Western town. Alas, Rastignak moves first and immediately crushes it. I end the turn with only 7 soldiers on the map!

However, I still have my untapped “reserve” that I can only call in my castle. I recruit twice the usual number of units (at the cost of flexibility in the future) and defend successfully against an attempt to retake Dayyalu’s castle. By the end of turn 12, I am back at the outskirts of the Xity with an army, and I manage to recruit another over two additional turns.

Unfortunately, my string of victories finally ends, and Rastignak demolishes my stack of 33 near Dayyalu’s castle with relatively few losses. I can’t really hope to rebuild and Dayyalu’s castle is taken turn 14!

The following turn, Rastignak can simply waltz into my castle and force me to throw in the towel.

Congratulations to Rastignak, though I am going to be a sore loser and claim that he had an incredibly powerful starting position (castle richer than mine, next to the Xity and to a town) and was very lucky with the one-impulse first turn, which allowed him to remove Dayyalu from the game effortlessly. I still believe I squandered several opportunities to win, in particular turn 8 where all I needed to do was do nothing in the Xity. You can read a more detailed account of the game on the forum where we described our moves.

Ratings & Review

Warlords, by Brian and Toni Beninger, published by Speakeasy Software, Canada

First release: 1978 on Apple II

Genre: Conquest

Average duration of a campaign : As long as it needs

Total time played : Unclear (PBEM). 10 hours maybe.

Complexity: Easy (1/5)

Final Rating: Obsolete

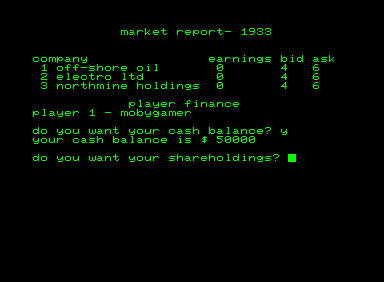

Context – Speakeasy Software is one of the very first video game companies, on which there is – for once – a lot of information thanks to the efforts of the Gallery of Undiscovered Entities, who interviewed the mom-and-pop founders Brian and Toni Beninger. This section will be no more than a summary of the long article the Gallery wrote about Speakeasy Software.

Brian Beninger, a manager at Statistics Canada, went to a small computer show in California (“a small bunch of guys and a few tables in a hotel“) and after returning to Canada ordered the whole Trinity: an Apple II (one of the first 10 according to him), a Commodore PET and a TRS-80. With a lot of computers and not a lot of software, Beninger created Speakeasy Software and convinced his colleague Randy Pack to port a board game Beninger had designed back in 1970: “Bulls and Bears“,

After Bulls & Bears, Brian Beninger made more games, but this time programmed by his wife Toni. By early 1978, the couple added three titles to their portfolio: Kidstuff, Microtrivia and of course Warlords, which Brian sold by touring the 30 or so North American computer stores he could find listed in the Byte Magazine. In one day, he received $3000 in orders and both Brian and Toni could quit their day jobs.

Operations scaled up after that, with international “non-American orders” (Brian mentions Australia) and Radio Shack ordering 5000 copies of each of the TRS-80 ports of Bulls & Bears and Warlords – Brian remembers selling 7000 copies of the game in total. Speakeasy Software also expanded its catalogue, both with games and serious software, including Dan Bunten’s first game: Wheeler Dealer$, which barely sold. This did not prevent the company from growing further, eventually buying other companies. Brian finally concludes : “like Steve Jobs, I decided I had to hire a more experienced management team. As with Steve Jobs, that management team kicked the original team out. Like Steve Jobs, I started another company.”

Traits – Warlords is hard to like nowadays. I have to concede that Warlords has chess-like qualities. While the game has a significant amount of randomness, you can generally know which stack will win in the case of a battle, so a large part of the game is about positioning your armies so you pin more forces than you commit or maybe “force” the movements of your opponent. Few wargames do this well, but Warlords delivered in 1978 already.

I don’t have any issue with randomness of the starting positions: Rastignak had overwhelmingly favourable starting conditions (large castle next the Xity and a town), but we should have generated maps until we found one that felt balanced. I think random turn duration (in number of impulses) generated interesting decisions as it forced you to balance risk vs reward and to have back-up plans. However, I reckon the extreme randomness of battle was unnecessary. As I understand the system, relative strength determines the odds of winning, and then whichever side won loses a random number of units between 1 and “everything except 1”; this rule can punish a player harshly through no fault of their own, and makes them unwilling to commit and bring the game to a close rapidly. At least it created interesting reversals of fortune.

Despite a great design for a BASIC game, I can’t say I enjoyed the game very much. First, it’s dry. The graphics are fully ASCII and the only narration are the rare random events and the one-page-and-a-half introduction that still manages to name-drop 4 fantasy locations, 4 fantasy characters and 2 other fantasy names. It’s a matter of personal preference, but the game is quite simply too abstract for my taste.

More importantly, it is just too slow to play. Warlords has a better UX than games from the early 80s, but it is multiplayer-only, which means I have to go through the motion of receiving an email and sending another for every one or two impulses. Players in hotseat in 1978 would not have had this issue, but then if I had been at a friend’s house I would probably have demanded something more fun – ideally something that doesn’t risk eliminating half the players in the first few turns before lasting almost forever.

Did I make interesting decisions? Yes, every impulse. Each action has to be carefully weighed.

Final rating: Obsolete. It is a rare case when I give an “obsolete” grade to a game with a relatively solid design and no critical UX flaw, particularly compared to the state of game design in 1978. Yet, I must; this ranking is also about my personal enjoyment of the game and alas I did not have a lot of fun playing it. I found Warlords too long to play for the limited enjoyment it procured to me. A turn limit and a bit more chrome, maybe, could have done wonders.

Ranking at the time of review: 79/175 – This is an impressive game given how early it arrived, but it did not pass the test of time.

For the sake of convenience, let me copy Rastignak’s take on the game below (from the forum):

I’m still kind of amazed that such a simple ruleset managed to create so many tense moments. The game never felt like a slog, but honestly it seemed more about lucky RNG rolls than deep strategy. I never really thought I was in a winning position until the very end – when I wiped out Scribe’s army in the swamp above the Xity and started steamrolling what was left. Even then, I mostly survived thanks to a few golden rolls at just the right time.

What I really liked, though, was the randomized move order and the different number of pulses each turn (“campaign”). That mechanic fixed a problem a lot of rulesets have, where going first or last can be a big advantage (or disadvantage). Even when it was just two of us left, turn order still mattered: if you went first, you had to plan around a possible double move from your opponent; if you went second, you were hoping for your own. The fixed recruiting order, on the other hand, definitely gave me an edge – especially late game. Since I recruited after Scribe, I could see where he placed his troops outside the castle and then counter him. A small tweak – like only letting players see their own garrisons during that phase – would fix that.

I played pretty aggressively, since it felt like the ruleset really favors attackers. Defending worked sometimes (especially at the Xity), but most of the time going all‑in paid off. And yeah, the Xity was the key: big income, great position, total map control. At first I hated having my castle right next to it (I actually thought Morpheus had the best spot), because I figured everyone would pile on me in a King‑of‑the‑Hill fight – and they tried to. But in the end, that position is what won me the game. I could grab the most valuable territory right away and usually defend it easily, since I could recruit in the castle and move troops to the Xity in one go.

Scribe really should’ve dug in at the Xity after taking it from me. Going for Morpheus’ castle was bold, but it was literally a bridge too far. That move probably cost him what could’ve been a win.

All in all, it was a great fun, and the game holds up surprisingly well for its age!