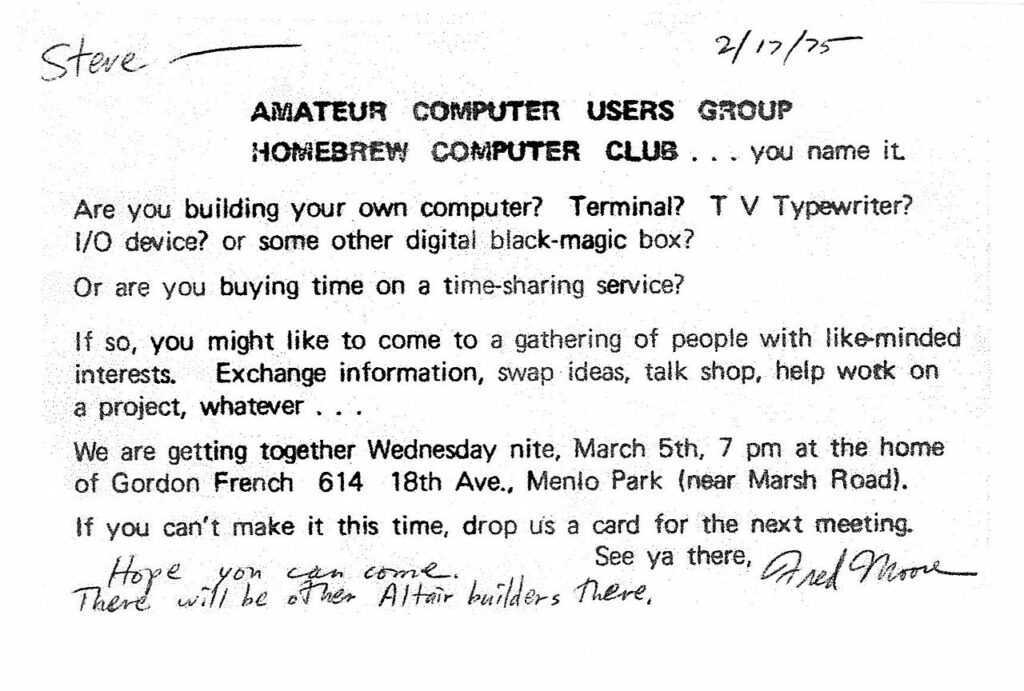

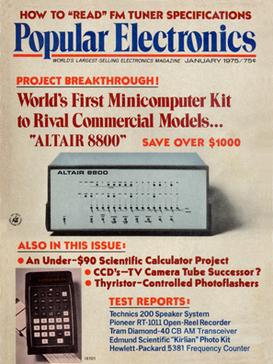

On the 5th of March 1975, a collection of computer hobbyists held the first meeting of the Homebrew Computer Club in the garage of an unemployed engineer called Gordon French. The centrepiece of the meeting was the new Altair 8800, a new computer by MITS (Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems), announced with fanfare by the January issue of Popular Electronics. Bob Albrecht, co-founder of the People Computer Company, had secured one of those marvels and brought it to the meeting for everyone to see it in action. One of the attendees – a 24 year old called Steve Wozniak – recalls this momentous event : “After [this] meeting, I started designing the computer that would later be known as the Apple I. It was that inspiring.“

But of course, this article is not about Wozniak and Apple, but about another attendee called Bob Marsh and his company whose designs played a short, pivotal and totally forgotten role in the history of our hobby. At the time, Marsh was an unemployed and quite simply broke engineer who was looking for ideas to launch a business. As it turned out, he garnered from the meeting two critical insights on the Altair 8800. The first one was that the demand for the Altair 8800 was extremely high (4000 units). The second was that the Altair had massive shortcomings, in particular a pathetic memory of 256 bytes, insufficient to even run BASIC. This was actually part of MITS’s strategy : sell a computer at cost so many could afford it, and profit on the premium components – for instance memory boards – that were required to make it actually useful. Marsh knew he had the know-how to undercut MITS. Alongside Gary Ingram, another meeting attendee, he decided to launch Processor Technology in April 1975 and to offer 4K memory boards. The plan worked beyond their wildest expectations, and they were immediately flooded with orders. A combination of luck and talent certainly played a role : the MITS 4K memory boards turned out to be woefully unreliable, with young MITS engineer Bill Gates remembering that “every one that came off the line wouldn’t work” ; in contrast Marsh’s memory boards worked perfectly. But there was something else : Marsh had a secret weapon called Lee Felsenstein.

Born in 1945 in or near Philadelphia, Felsenstein came from a family of artists and engineers. As a child, he doodled machinery diagrams, and by 12, he was already pursuing electronics courses. Sputnik in 1957 captured his imagination, not because of the prowess of sending a satellite into orbit, but because of the prowess of sending a signal toward Earth. At a Science Fair the following year, Felsenstein submitted a model satellite he had designed and assembled with a friend, complete with solar cells and radio signals.

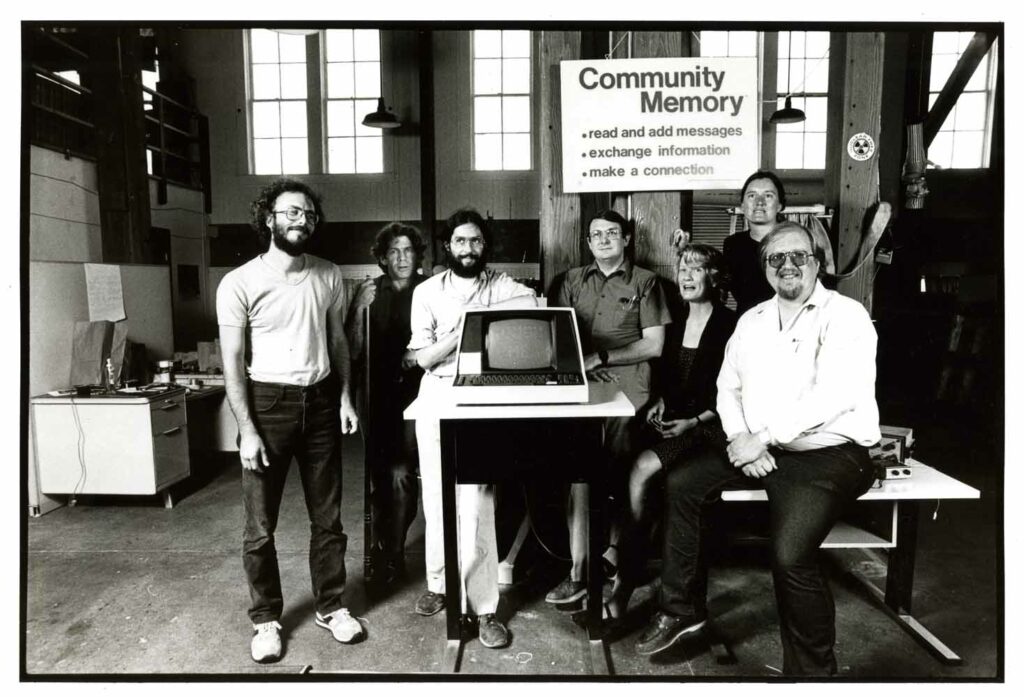

In 1964, Felsenstein enrolled in engineering at UC Berkeley, where he became immediately embroiled in the student New Left activism of the 60s, starting with the Free Speech Movement : picket lines, sit-ins, demonstrations, the whole deal. This derailed his studies for a time, and starting in 1968 he elected to work for Ampex Corporation. This move turned out to be a boon both for him and for the underground press that had started to flourish in Berkeley. Ampex Corporation had computers – and even better, one of the few cross-state computer networks of the era. Felsenstein then returned to Berkeley, finished his degree in 1972 and brought his talent to Resource One, one of the many projects blossoming from an “underground commune” of ethical hackers that had set up a base in a warehouse in San Francisco. Resource One’s main objective was to empower “normal” people to use computers, including for gaming, hence the name Bob Albrecht had given to its publication : People’s Computer Company. Initially tasked with maintaining an SDS 940 mainframe that the commune had somehow acquired, Felsenstein became the hardware expert of the commune and as such of the People’s Computer Company. In 1974 he moved to a more ambitious project : Community Memory, a network connecting the warehouse to a handful of public terminals (with teletypes !) in San Francisco and beyond.

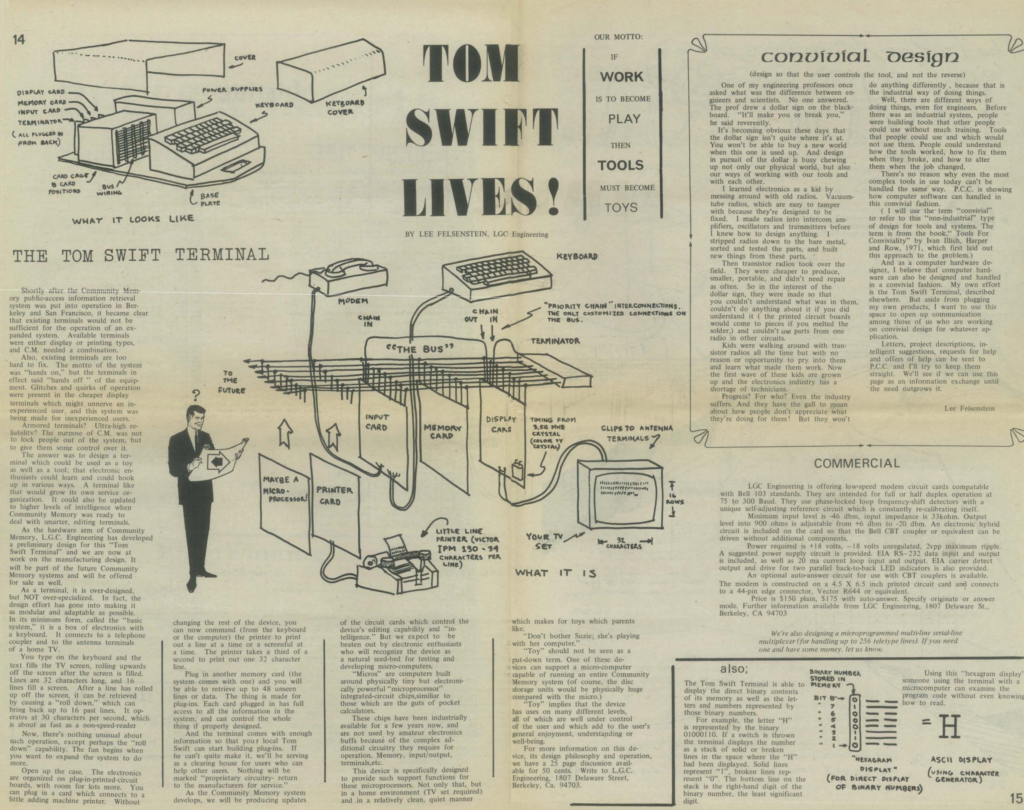

Community Memory would deserve an article of its own, but suffice to say for our purpose that one of the key roadblocks it encountered was hardware : terminals were expensive and hard to maintain. Felsenstein wanted a solution both cheap and “convivial“, a concept coined by Ivan Illich to describe technologies that could be understood and modified by their end users. Thinking about the issue, Felsenstein came up with the idea of the Tom Swift terminal, a terminal that could be connected to any TV. He published the design in the November 1974 issue of People’s Computer Company and requested feedback and comments.

One of the responders was Bob Marsh. In truth, Felsenstein had already met Marsh in his early days at university, but the two had little in common then. While Felsenstein had neglected his studies because of his activism, Marsh had neglected his studies for the life of a university jock. A trip to Europe changed him, and he returned with a new determination to do something with his life. A short and lucky gig as chief engineer for Dictran (a company designing dictaphones) finally gave him a direction : design and build electronic devices. He had built an improved Don Lancaster’s TV typewriter, whose blueprints had been published in the September 1973 issue of Radio Electronics, and he thought the machine might interest Felsenstein. The Lancaster/Marsh TV typewriter turned out to be a technical dead-end for Felsenstein’s purpose ; still, despite their different objectives in life – social revolution for Felsenstein and personal profit for Marsh – they bounded over their common interest over electronics. Both also lacked a workshop, and they decided to rent together a garage from which Marsh would start whatever business venture he would come up with. That was in January 1975. Two months later the Homebrew Computer Club met for the first time, and Marsh had a project.

It is hard to convey how lucky – or well-inspired – Bob Marsh was to have such a neighbour. Before Processor Technology had produced its first memory board, it had a column from Lee Felsenstein announcing their arrival in the May 1975 issue of People’s Computer Company. Even better, Felsenstein could vouch for the quality of those memory boards because according to Fire in the Valley he had designed them in the first place ! In any case, this column kickstarted Processor Technology, presumably much more so than the timid ads published later in June and July 1975 in Radio Electronics, Popular Electronics and Byte. The People’s Computer Company would mention Processor Technology in every 1975 issue, though starting from September Felsenstein would mention his involvement with them. Of course, from Felsenstein’s point of view, it was hardly a conflict of interest and more of a political stance : while he was frequently freelancing for Processor Technology his ask was so meagre that Marsh felt compelled to negotiate his fee upward. Felsenstein advertised Processor Technology quite simply because they had better and cheaper products and as such brought the computer closer to the masses. In addition, while Marsh was in here for the cash he was still closer philosophically to Felsenstein than to whoever managed MITS in the distant Albuquerque.

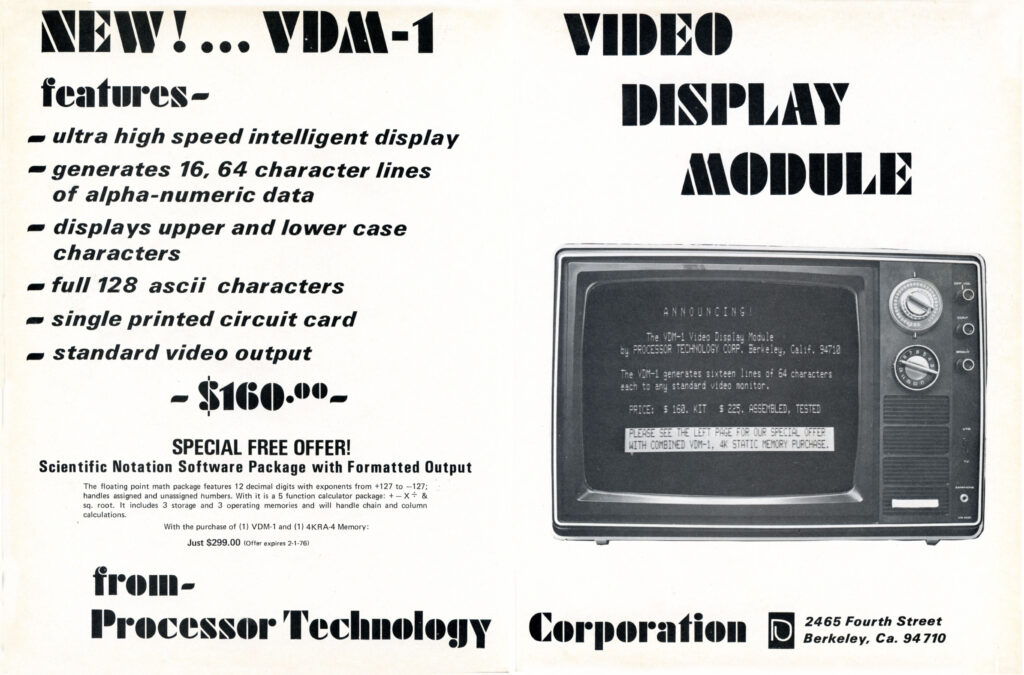

After the success of the 4K memory board, Marsh and Ingram decided to carry on in their niche by improving everything Altair. One of these improvements proved to be more pivotal than the others. The crucial issue with affordable computing in 1975 was, surprisingly, the teletype : the one provided by MITS cost $1500, more than the Altair 8800 itself. Processor Technology had provided its customers with a cheap adapter to plug unofficial teletypes, but these were just as expensive. Still, those adapters sold extremely well, and Marsh saw the business opportunity. He made Felsenstein an offer he could not refuse : if he could adapt his Tom Swift terminal (never built thus far) to connect the Altair 8800 to any TV screen, Processor Technology would sell it and pay him royalties. Roughly 3 months later, Felsenstein delivered. The device, called VDM-1 [Video Display Module 1], did everything it was supposed to do, and then much more : instead of just “adding” lines at the bottom like a printer or any earlier TV terminal would do, the VDM-1 could update any pixel on the screen. At a cost of only $200, it was a revolution for computing. As Felsenstein put it many years later : “You took two devices [the computer and the teletype], each of which cost $1,500, approximately, merged them together. You got something that still cost $1,500 and outperformed the original system by many orders of magnitude.” Processor Technology sold 10 000 units in total, which meant that for once Felsenstein was properly compensated through royalties.

Everyone who toyed with the VDM-1 immediately understood its wild potential. Steve Dompier, yet another attendee of the first Homebrew Computer Club meeting and now employed by Processor Technology, immediately worked on making real-time games : the action game Target and the space strategy game Trek80, a mix between the two superstars of mainframe gaming : Mayfield’s Star Trek and Trek73. For the first time on a computer, the games were “dynamic”.

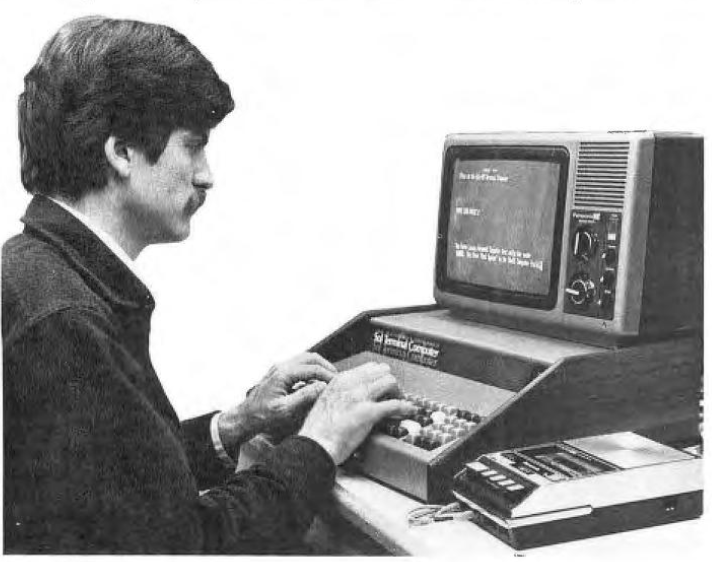

Played here on a SOL-20 emulator

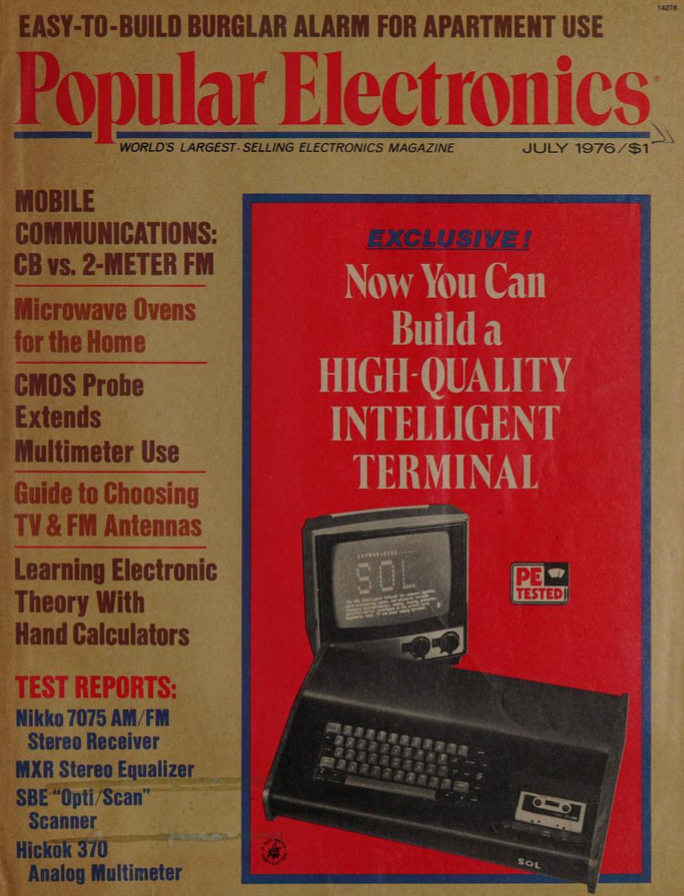

Les Solomon, technical director of Popular Electronics, did not miss the importance of the VDM-1 either, and he made Marsh an alluring offer : if they could provide the design of an “intelligent terminal” within a month, Popular Electronics would feature it on its cover. I am not clear what either Solomon or Marsh understood by “intelligent terminal” and whether they understood it the same way – the concept was ill-defined in 1975. When Marsh discussed it with Felsenstein, what he proposed was already almost a computer, with, according to Marsh’s vision, the same 8080 chip as the Altair to power it. It took a gruelling 45 days and considerable back-and-forth for Felsenstein and Marsh to finish the design of the project ; by then it had indeed become a full-fledged computer, called SOL in honour of Les Solomon. The fact that the SOL was now a computer worried Marsh, Popular Electronics ran a lot of ads for MITS and was in any case unlikely to run two DIY articles about computers in such a short timespan. When Marsh and Felsenstein demonstrated the SOL Intelligent Terminal (SOLIT) to Solomon, they made sure to remove the ROM card so the device could “write, store and edit programs for transmission to a computer or a hard-copy device” but not run them. Solomon was not fooled and he asked why the SOLIT could not be turned into a computer by just adding a ROM card. In a beautiful “I know you know” answer, Felsenstein quipped : “Beats me“.

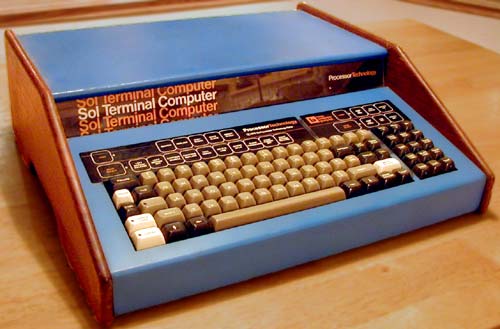

The SOL-20 computer (and a stripped-down version called the SOL-10 that did not interest anyone) made its grand opening shortly during the Personal Computing ’76 show in Atlantic. MITS had co-organized this event, only to see their competitor Processor Technology impress the 13 000 visitors with their slick machine. Marsh and Felsenstein had indeed kept busy between Solomon’s review of the terminal and the release of the article. On the hardware side, Felsenstein and Marsh wanted the computer to sit proudly in the living room – where the TV presumably was – and they spent considerable efforts on the casing, even modifying the electronics so the overall shape looked nice. With wooden panels and an integrated keyboard, the SOL-20 had the “glorified typewriter” look that pleased Marsh because it was marketable and Felsenstein because it was as convivial as a computer could be ; it was a look that computers would keep for the upcoming decade. Marsh had also the flair to sell the computer whole (including of course the critical VDM-1) and not in a kit, with BASIC onboarded. While I am not competent enough to comment on the technical qualities of the SOL-20 compared to its peers, what’s sure is that it was the first “plug-and-play” computer in history. “Play” in this case should be taken quite literally : the SOL computers were the first ones designed (also) with gaming in mind. Processor Technology’s order book was immediately filled in, with the first computers to be delivered early 1977. The era of home computer gaming had started.

This ends an article that for once did not feature any wargame. Investigating the history of the SOL-20 to prepare my article on its games, I realized the forgotten importance of the VDM-1 and the SOL-20 and that no one had written online history of them. The next article will be a BRIEF for Trek80 and then, finally, my coverage of the SOL-20 wargames. I will also cover the rest of the history of Processor Technology and its quick demise after the release of the 1977 Trinity.

Source :

Note that sources vary on some details, in the interest of narration I went with what seemed to me the most probable every time.

- Stan Veit’s History of the personal computer by Stan Veit, 1993

- Fire in the Valley – the making of the personal computer by Paul Freiberger & Michael Swaine, 1999

- Oral History of Lee Felsenstein, Computer History Museum, 2008

- iWoz : computer geek to cult icon, Steve Wozniak, 2006

- People’s Computer Company, all 1975 issues.

- Build SOL, an intelligent Terminal, Popular Electronics, July 1976

- Product Review : VDM-1, Byte, December 1976

- SOL, the inside story by Lee Felsenstein, in ROM, July 1977

- Solomon’s Memory, Atari Archives, date unknown

- Community Memory: Precedents in Social Media and Movements, Bo Doub, 2016

- March 5, 1975: A Whiff of Homebrew Excites the Valley, Wired, 2009

- The SOL-20 archives

Lee Felsenstein has a Patreon where you can help him write his book. He is a fascinating character and I am now contributing.