(ZX81, Ère Informatique)

– Lieutenant Narwhal, we understand you don’t want any additional Star Trek assignments

– That’s correct, Sir! I did all of them: Star Trek (1971), Star Trek (1972), Star Trek (1973) and Star Trek (1974?), and countless clones not named “Star Trek”

– What about – let me finish – Star Trek ON THE GROUND!

Rigel is an early game from ERE Informatique and the first wargame-adjacent game that I would describe as part of what wasn’t yet called the “French-touch”: a typically Gallic combination of cinematic aesthetics, high-concept unique ideas and unconvincing gameplay. Surprisingly, Rigel nailed those 3 defining elements on a puny ZX81!

The objective is to cull the pirate population of the eponymous planet with an armed “shuttle” and literal lightning reflexes. “Cull”, because you win long before you have destroyed all the pirates on the planet, so I suppose the game wants to you to help a fragile ecosystem of civilians and pirates reach its natural equilibrium.

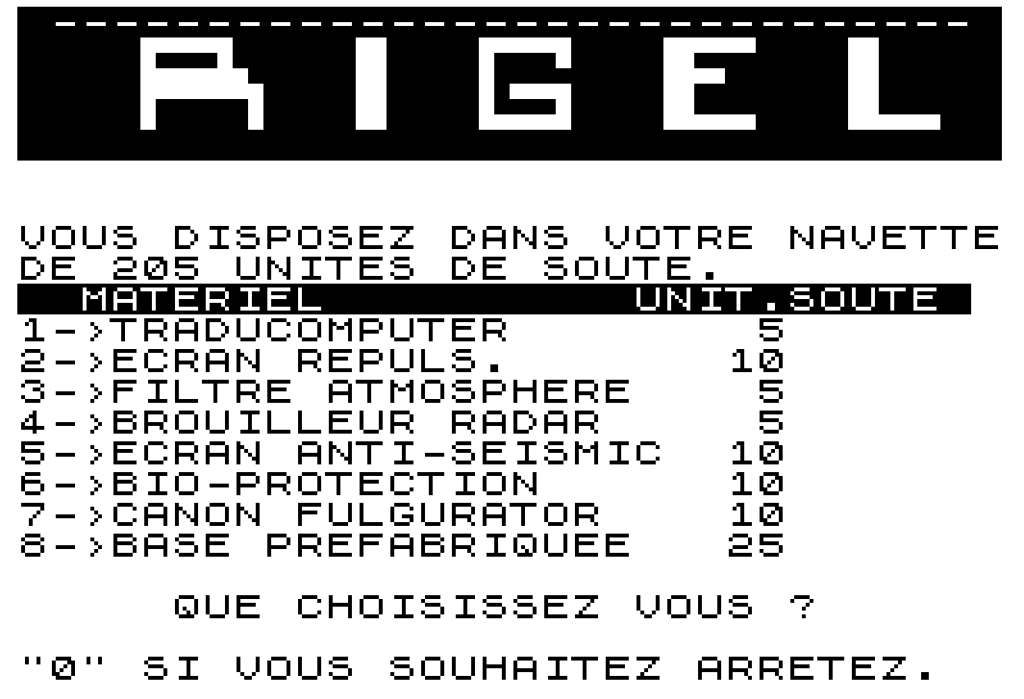

Rigel opens with a menu asking me which equipment I want to buy for my shuttle. All equipment could be critical to my mission, but there are no tough decisions because I have enough currency to buy all of them! I take one of everything and two pre-fabricated bases (the only item that can be bought more than once), keeping 100 “cargo hold units” in reserve.

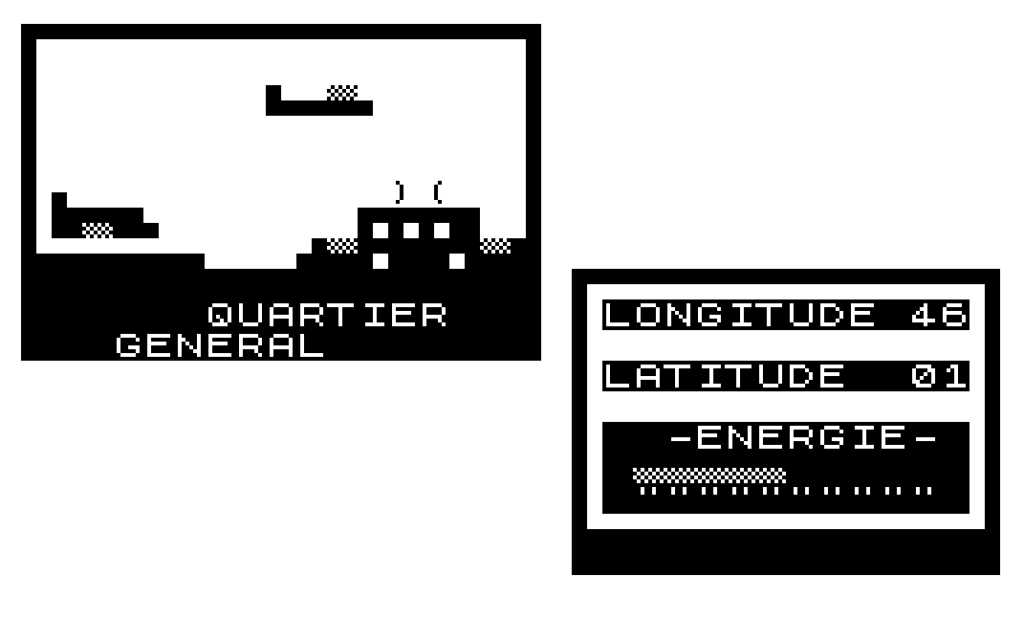

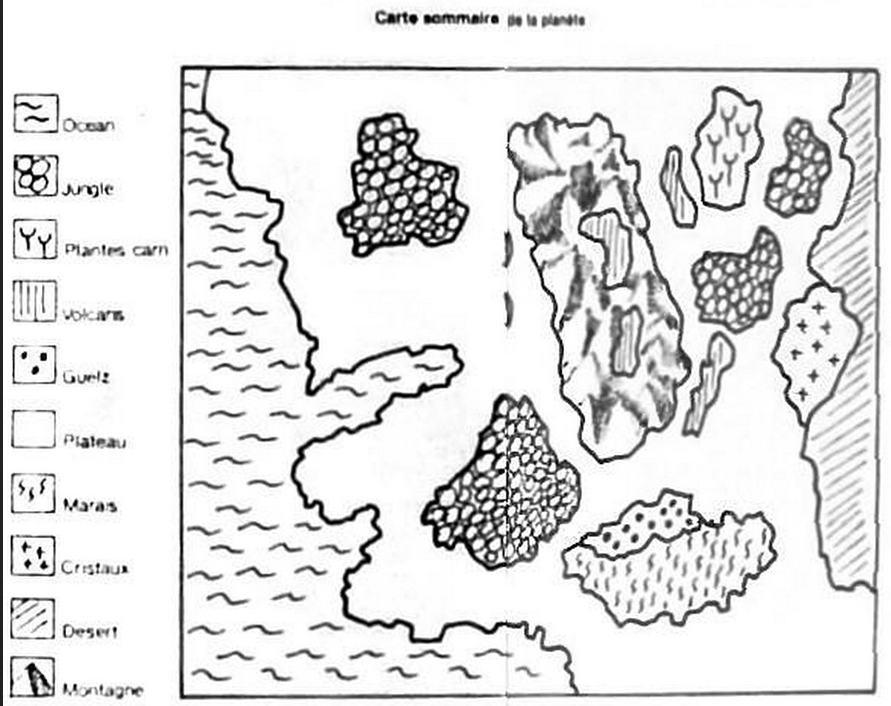

When I’m done, I start the game for real in an HQ in the North-West corner of the map.

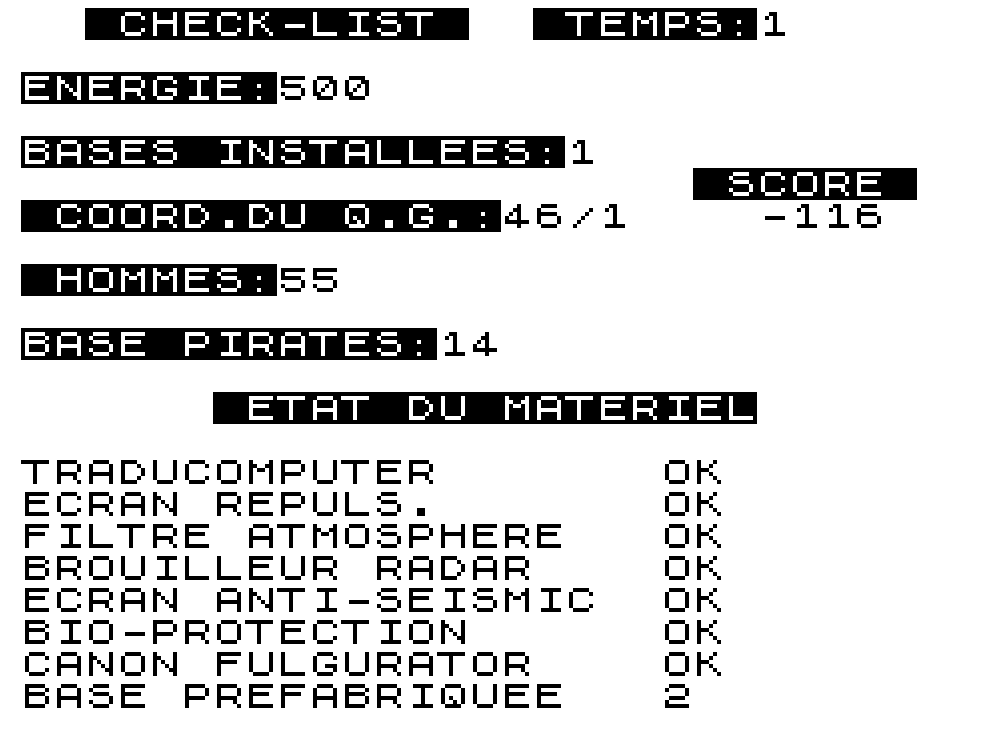

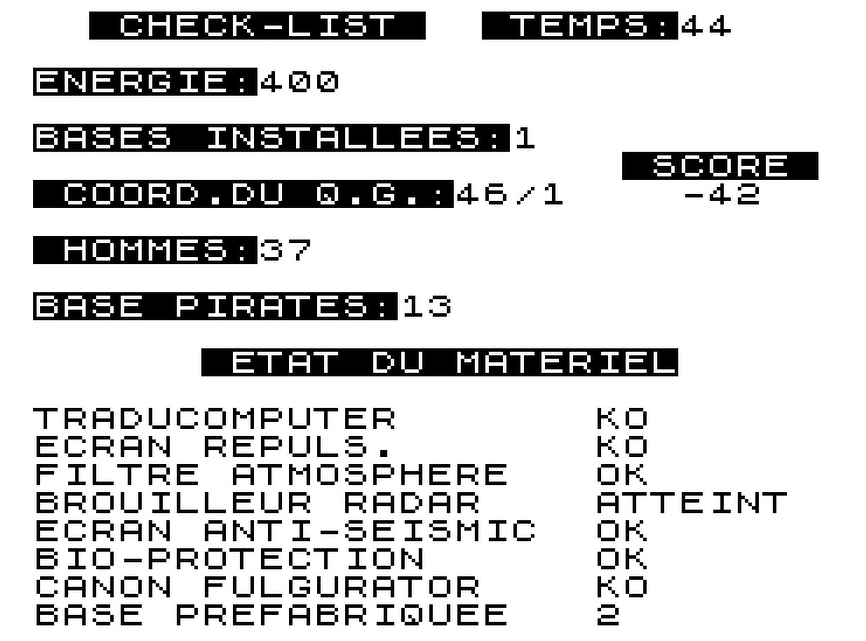

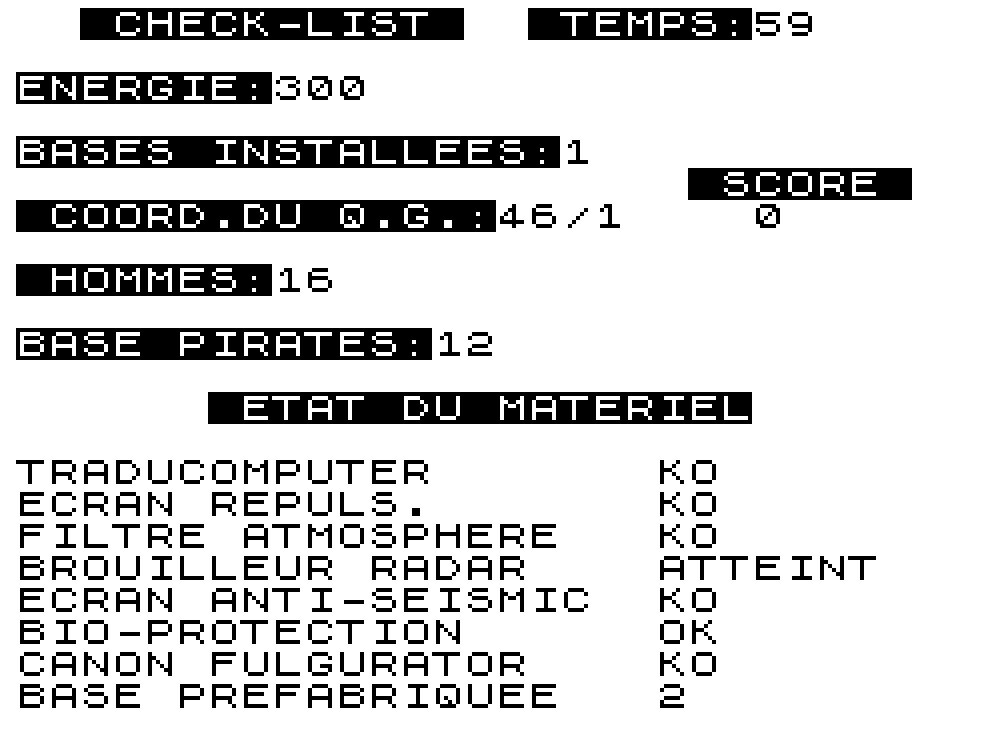

In addition to the main view, there are three side menus in the game. The first one is the status screen:

In addition to the status of my equipment, the important info is the number of men in my crew (“hommes“, it’s the 80s so it’s male-only) – those men serve as “health points” for my ship.

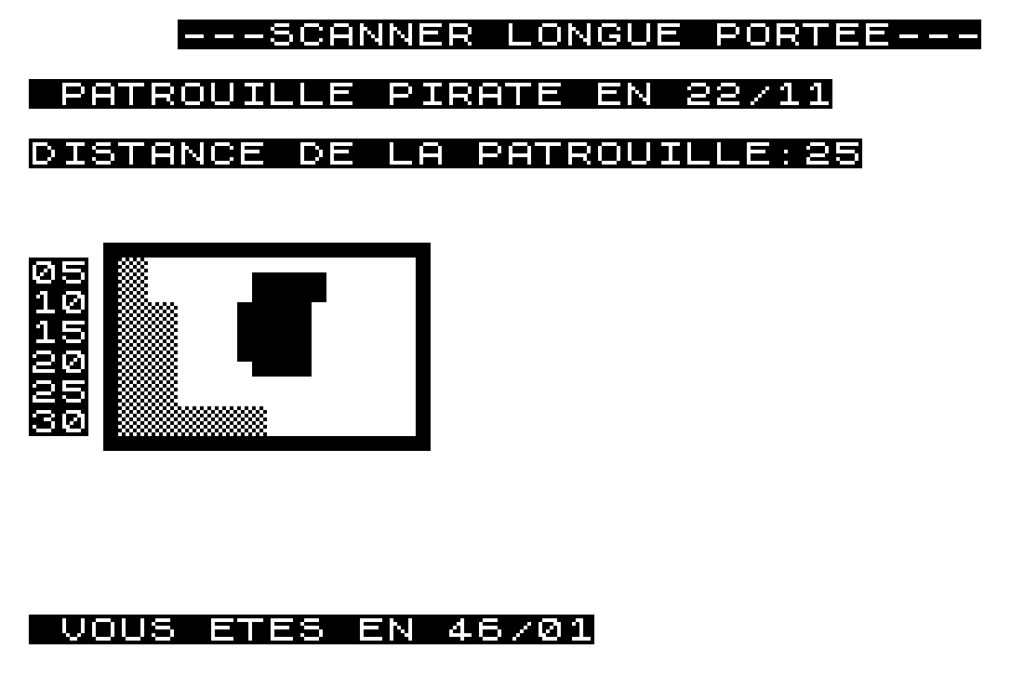

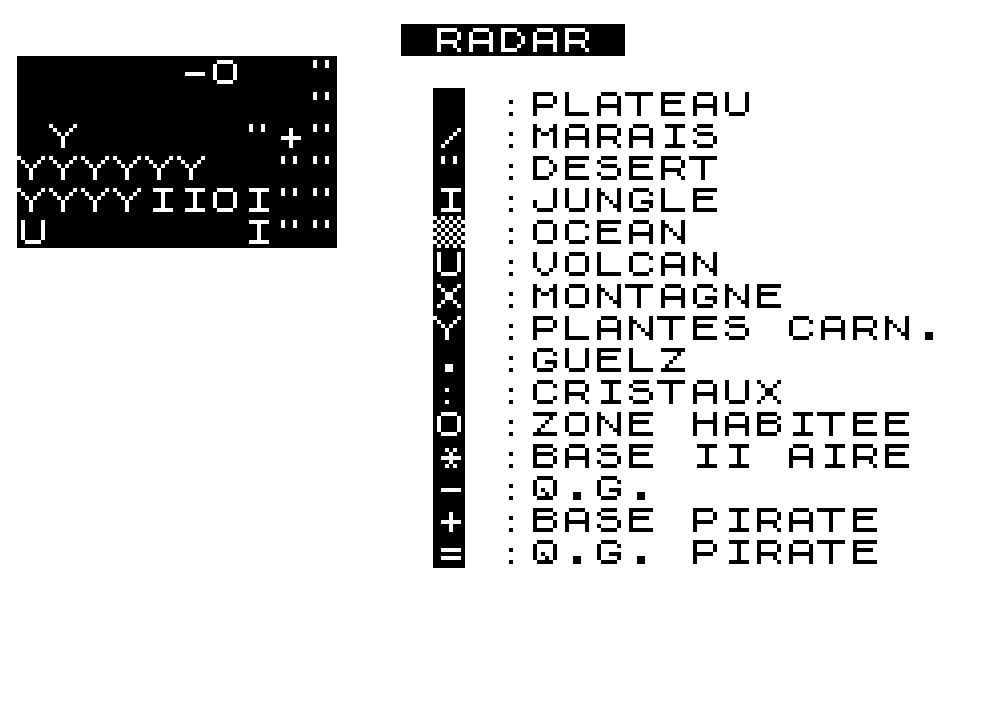

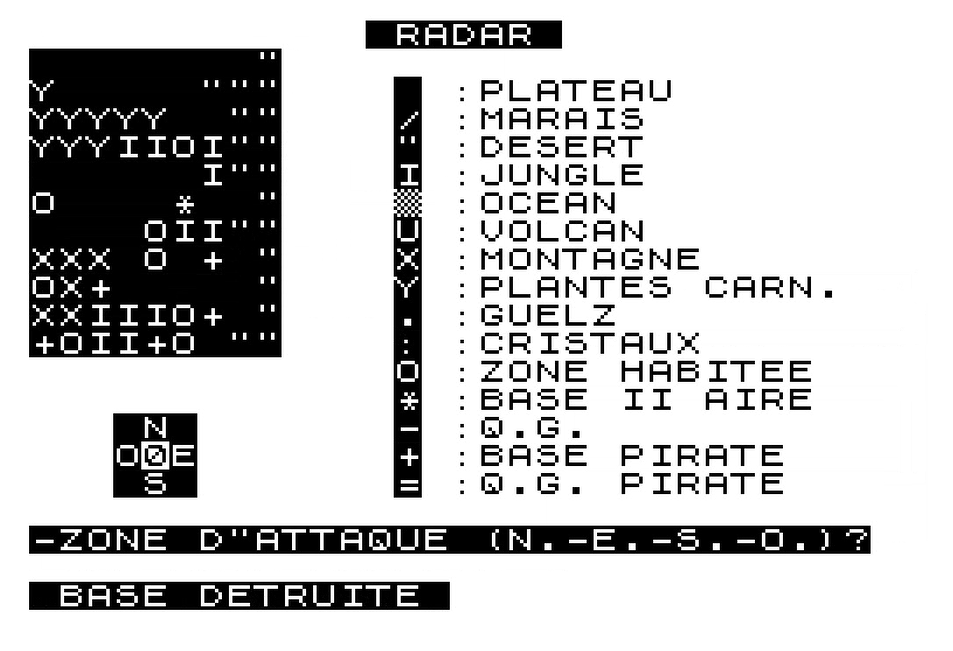

The other two are the radar screens: the first one is long range and is mostly useful to see where the pirate patrol is. The second one is the one you’ll really use to navigate.

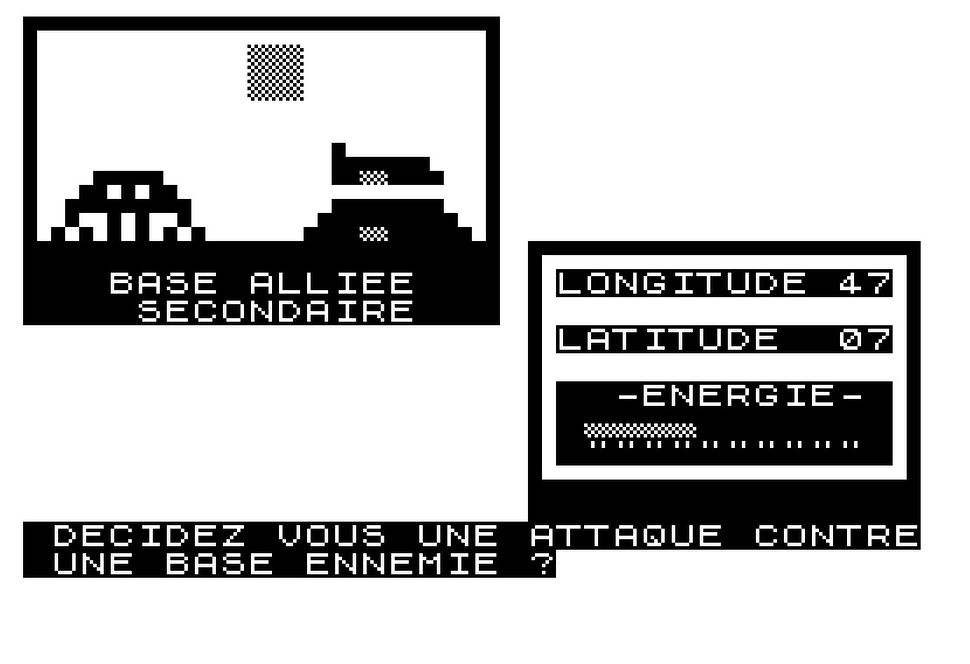

I can see a pirate base (+) South-East of the HQ so that’s where I am heading. After a short journey, I reach the pirate base:

I hang around in the area for a few seconds, pressing random keys to skip turns until the pirates notice me and attack, thus triggering the action phase of the game. This is where the lightning reflexes are needed: to win you need to shoot when the target appears on the correct line, and even at historical speed you have a fraction of a second to do so. There is no time limit, but you must repeat the feat 3 or 4 times and have only 15 “ammo” to do so!

I manage to destroy the enemy pirate with my last shell, and this destroys the pirate base as well. Checking my short-range radar, I find another base further South and move to engage. Unfortunately, this time I fail to destroy the enemy and receive damage and casualties!

It gets worse: with my Fulgurator Gun “KO”, I have only 8 shots per battle – and I am locked in successive combats with odds strongly against me. I expect to lose the game, but after 3 defeats I manage to win the battle by some sort of miracle, destroying the pirate base!

My ship is a wreck. I immediately deploy a prefabricated base to repair my ship for free – the alternative is to limp back to HQ where I would have to PAY for the repair!

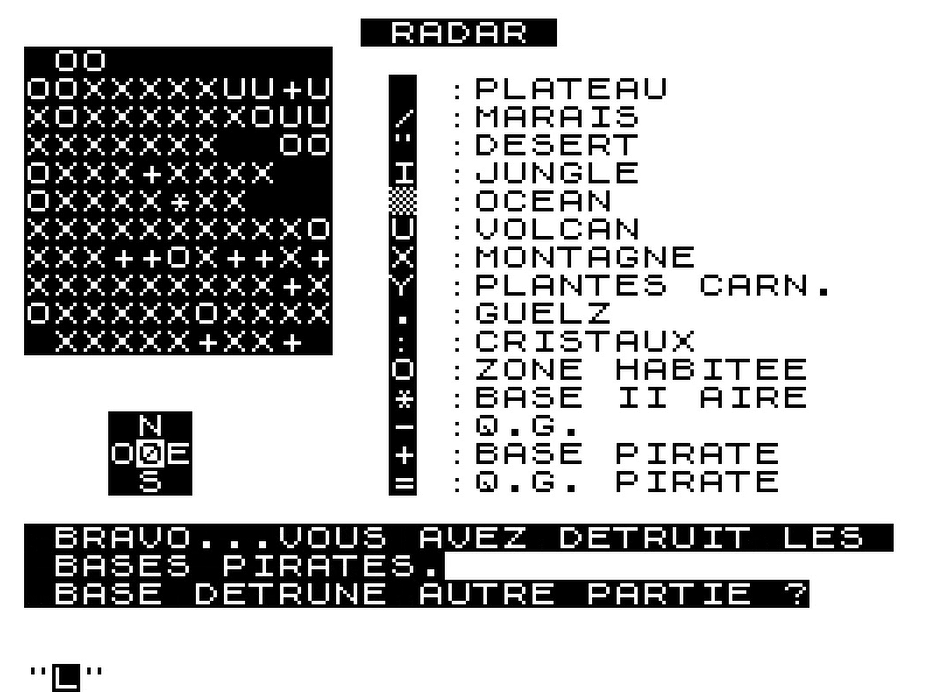

Another perk of the prefabricated base is that I can order air strikes from it. At one press of a button, I annihilate 5 pirate bases South of my position! Clearly, the “prefabricated base” came with bombers and missiles.

I am also attacked by the pirate patrol – presumably because my scrambler took time to repair, but then my guns did not – and I defeat them without issue.

The base does not restore crew, so I fly over some inhabited areas with my traducomputer to recruit a few replacements, though once I reach 22 crew members I don’t receive any more.

There isn’t much more to show and luckily I won’t have to. I fly East for a while, check my map and discover that I am in the middle of a pirate base motherload: 10 bases on my radar. I immediately deploy a base and order air strikes South, destroying 8 of them. This immediately wins me the game!

What a disappointing finale for a game with a lot of potential! This is exactly what the French touch is supposed to be about: a lot of excitement, and then a huge letdown!

Ratings & Review

Rigel by Olivier Malinur, published by Ère Informatique, France

First release: November 1984 on ZX81

Genre: Air Operations, I suppose.

Average duration of a session: 30 minutes

Total time played : Two hours

Complexity: Low (1/5)

Final Rating: Totally obsolete

Context – I have already written about the beginnings of Ère Informatique, the first French video game company founded by frustrated musician Philippe Ulrich and medical student Emmanuel Viau. As a musician, Ulrich had been given a chance by Philippe Constantin, the art director of Pathé-Marconi who went above and beyond to find and support promising musical talents, and so Ulrich wanted to be, to quote him, “the Constantin of video games“. The first find was Marc-André Rampon and his complex air combat simulator Intercepteur Cobalt (Novembre 1983)- Rampon prefered to be paid in shares and one thing leading to another he soon became the head of sales of Ère, freeing Ulrich and Viau to focus on the “finding talents” part of the activity.

Late 1982, Olivier Malinur, a student in geology in Reims, bought a ZX-81 and immediately learned to code on it – first in BASIC, then in Assembler. His first game was a story of pirates which, as all pirates are prone to do, were looking for treasure on an island. This unpublished game then became the skeleton of Rigel, based on a sci-fi novel whose title Malinur has forgotten – what’s sure is that the game was not inspired by Mayfield’s Star Trek (which he did not know about) despite a few shared features. After finishing the game in one month, there was the question of selling it. The reference of gaming in France in the early 80s was the generalist magazine Jeux & Stratégie, and so Malinur simply called them for information, and they sent him the contact of Emmanuel Viau. At 18 or 19 years, Malinur took the train to Paris to meet Viau, who was impressed by the game and had little feedback for Malinur except improving the visuals of the explosions. This was a tall order on a ZX81, and it took Malinur two weeks to do it – but it was well worth it, because Ère then accepted to publish Rigel, paying the young Malinur either 3000 Francs or 5000 Francs in advance on royalties. It would be only the beginning.

Traits – As a disclaimer, the manual of Rigel is lost, so its lore and possibly part of its depth is at the moment lost. However, it would be hard to claim that the game is difficult: you could easily win the game in a few minutes without combat by just moving on the map, deploying mobile bases and sending a few air strikes – and maybe the game is better this way, given how stale combat is. What really makes Rigel stand out, however, is how immersive it manages to be with the 16K of memory of a ZX81. The visuals are good-looking enough that I explored a bit after finishing the game, and then tried to extract the strings from the code to see what I missed – not something I usually do. When you travel above the Selkar mountains, the living lake of Guelz or the yellow marsh, you can’t help but imagine that there is more to the game than just wiping a few pirate bases. There isn’t, of course, but if you played the game in 1984, you were used to letting imagination carry most of the load.

Did I make interesting decisions? No, except “do I win the easy way or the stale combat way“?

Final rating: Obsolete. It’s a curio more than a wargame.

Ranking at the time of review: 115/178. A poor ranking as a game, but it does not translate how impressed I was by the visual and ambition of the game – it is also by far the best game I played on ZX81, and punching well above its weight.

Reception

Forgotten today, Rigel was a critical and commercial success in France. Hebdogiciel ranked it as the best ZX81 software from its release in November 1984… until they stopped ranking ZX81 games in July 1985. Olivier Malinur also remembers seeing an excellent review in Jeux & Stratégie, but I have been unable to find it in the Jeux & Stratégie archives. Malinur remembers the game sold very well and that autograph sessions were organized by Ère Informatique in computer shops, during which he sometimes had to answer very specific questions from the fans about the lore.

We will see more of Malinur, as he will release the RPG Argolath in June 1984 (the second French RPG, hopefully soon described on a companion website) and then the Greek polis management game Ethnos in 1986 – after which a nomadic geologist career prevented him from making more games.