[IBM PC, Brøderbund ]

– Lieutenant Narwhal, have you seen Gladiator 2?

– As far as I am concerned, Gladiator never had a sequel, General!

– Perfect! Just perfect! I have a mission for you! We must stop the sequel from happening, and we believe we found a solution for that!

I’ve finally reached The Ancient Art of War, which is not only the first game on this blog that I had played before, but a game that has been there in my life as far back as I remember. I have played The Ancient Art of War in & out, and it has also been throroughly covered by the DataDrivenGamer, who played every scenario in the game. To keep things fresh, I therefore asked whether a commenter would like to make a scenario I would play. Commenter Operative Lynx answered the call, and so I am happy to play Those About to Die.

So we’re back to the beginnings of Gladiator, except I am commanding the Germans and I must end the movie right after the introduction. I like this story!

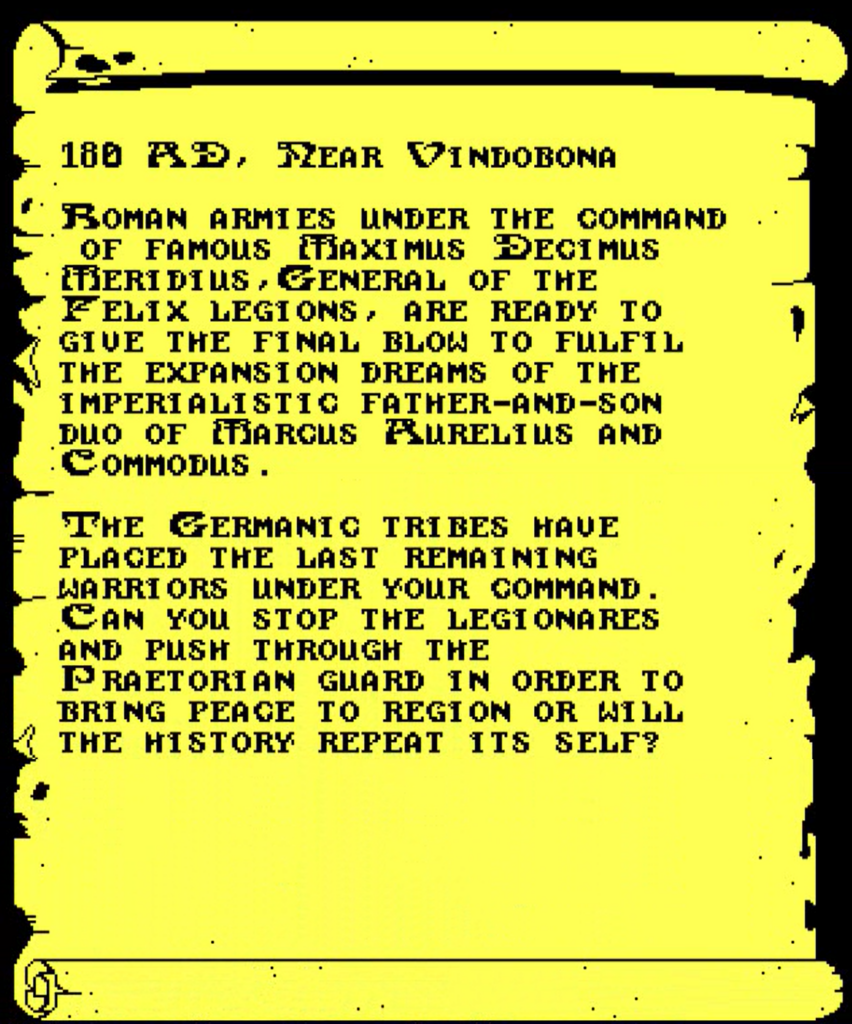

Ancient Art of War allows you to change the rules of the game, and some of them are extremely impactful. Operative Lynx chose to combine “Villages Supply Food” with “Forts Don’t Supply Food“, which means sieges are on the menu. Additionally, forts will generate troops over time, there will not be a fog of war and finally the forest is “sparse”.

Of course, my AI opponent will be Caesar – not the most dangerous, but certainly the most thematic.

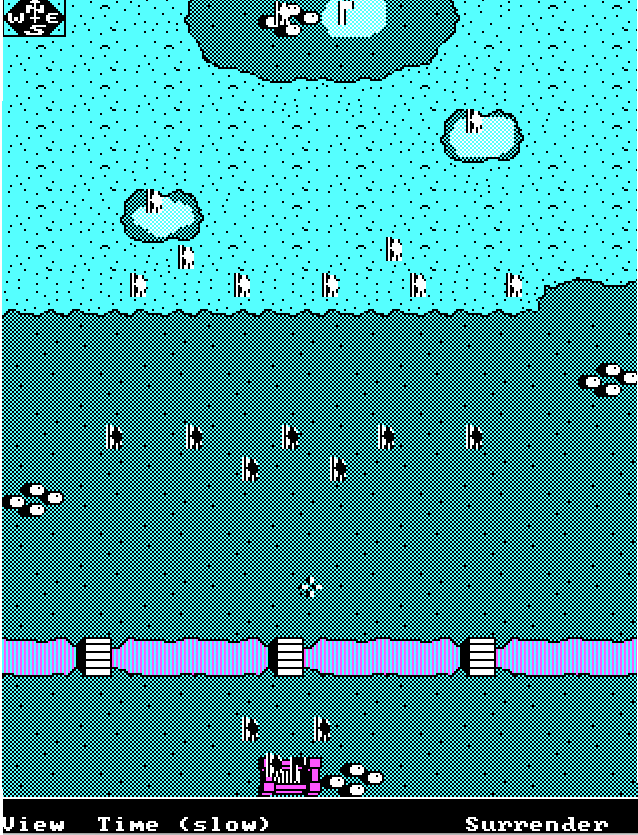

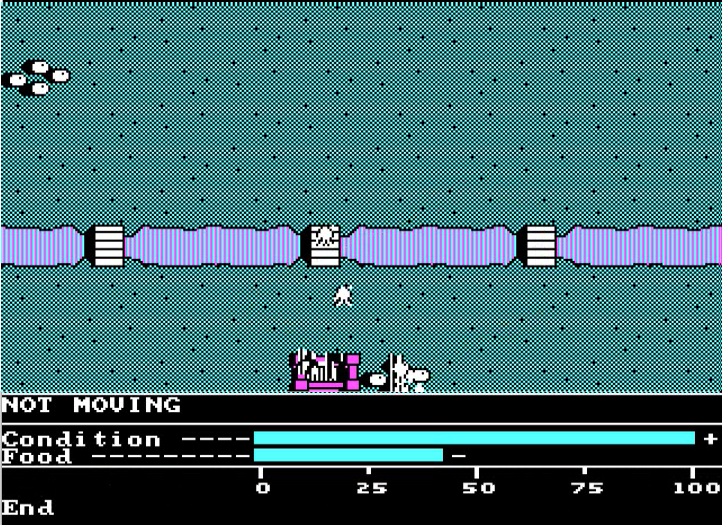

The starting map is easy to read, I hold the forest in the top half of the map, and the Romans hold the plains in the Southern half. Each side has only one flag, with the Roman one being protected by the walls of the only fort of the map, a fort that also generates troops so I can’t only play defense. I immediately notice how few villages there are: four in total. In the ruleset of this scenario only villages can provide food, so if I take the two central villages any Roman attack will peter out.

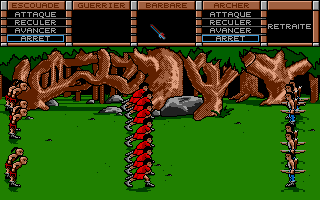

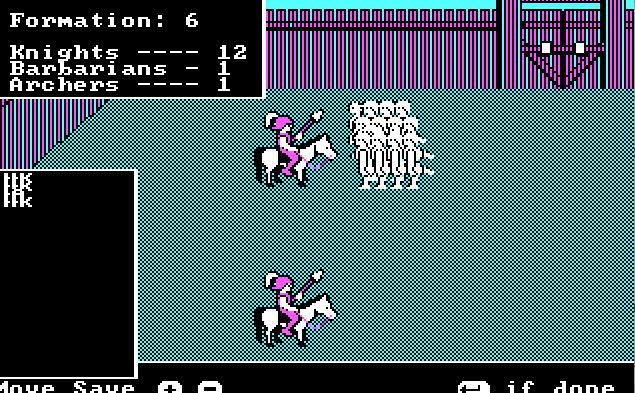

The game tells me that both forces are roughly equal in size (around 140 men on each side), but this hides a nasty surprise when I check the composition of the forces. There are 3 types of combat units in the game: Knights, Archers and Barbarians – my force is mostly barbarians and archers while the Romans are mostly knights and archers.

That’s a huge issue for me, given the specs of those units:

- The knights focus on the barbarians and usually win duels against them thanks to their armor,

- The barbarians usually beeline for the archers and are faster than the knights,

- The archers shoot whatever is in front of them – knights, barbarians and other archers, and according to the manual they will make short work of the knights.

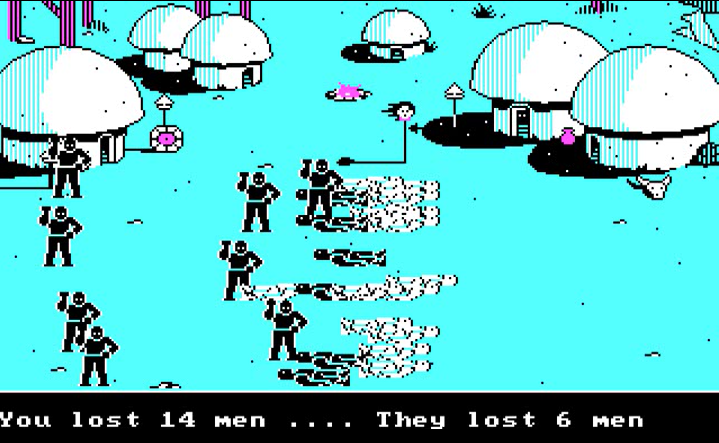

You would would think that the barbarians counter the archers, but in reality archers will have killed most of the barbarians by the time the latter close the distance so really they “counter” as in “at the end of the battle, both sides have lost everything”. By contrast, a group of knights will absolutely slaughter a group of barbarians. I am reminded about the balance of the game when I intercept a group of archers with a group of barbarians in the middle of the map.

Apart from this mutual annihilation, the plan works as expected. One of my groups of archers singles out and destroys a group of Knights, the rest of the Roman army goes through the middle of the map while I occupy the villages:

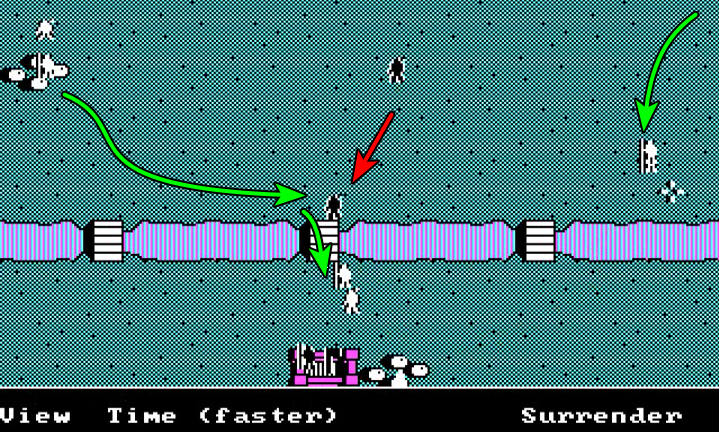

There is a risk in my plan however: between my flag (losing it is an instant defeat) and the bulk of the Roman forces I have only two units: one group of archers in contact, one mixed group near the flag. My archers use a delaying method: engaging combat, shooting a few arrows in the narrow forest battlefield and then retreating. This is exhausting for them, but they inflict casualties and tire the Romans – who are also low on food. This should give enough time for another of my units to come back in defense, and two healthy units should be enough to deal with 5 exhausted Roman armies. I hope.

Meanwhile, I move from the central villages to the Southern one near the castle. I bypass two enemy armies that decide to double back to retake the village.

A series of battle ensues. The Romans are exhausted, but their army has a better unit composition so I take some significant losses.

Still, I eventually destroy the two armies, which means the fort is under siege.

In theory I could just overrun the castle: one unit locks the Roman army in battle: you can choose not to play in battle, in which case it is played automatically while the rest of the game continues, and so a second unit can just waltz into the fort unopposed and take the flag. But where’s the fun in that? I will win through a siege.

In the North, the Roman main force, which has not eaten since the beginning of the game, have finally managed to get rid of my skirmishers (I forgot to manually resolve the battle and retreat), but they’re in such a poor condition that I don’t consider them a threat anymore.

When the Romans in the fort finally run out of food, they sortie their army and try to take the village – but they’re one army against four well-fed ones.

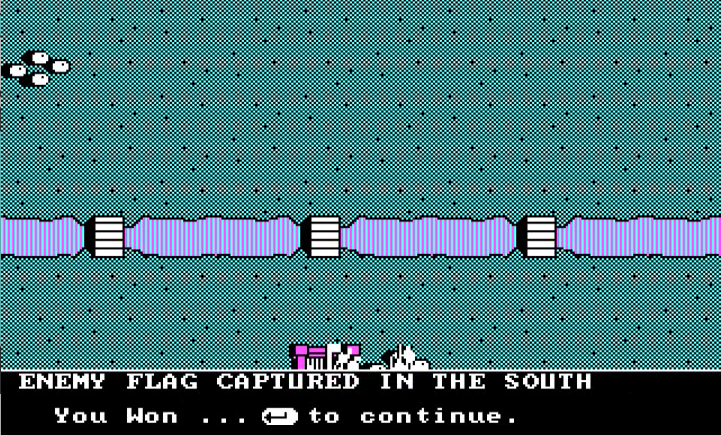

After destroying them, I just have to enter the fort where an army of one soldier has been left behind, and seize the flag.

With this victory, the Germans kill Marcus Aurelius, Decimus Meridius and Commodus. This means we don’t have a Gladiator 1 movie either, but that’s a price I am willing to pay for the sequel not to exist.

I found the scenario on the easy side, but it was fun nonetheless so – again – thank you Operative Lynx. The DataDrivenGamer has added it to his package of now five custom-made scenarios if you want to test it.

Ratings & Review

The Ancient Art of War by Dave & Barry Murry, published by Brøderbund, USA

First release: January 1985 on IBM-PC

Genre: Operations

Average duration of a scenario: 15-30 minutes

Total time played : Counting my youth – hundreds of hours

Complexity: Average (2/5), but feels like Low (1/5)

Final Rating: ☆☆☆☆

Context – In 1980, brothers Dave Murry (an electrical engineer) and Barry Murry (an air traffic controller) realized that one could make a career out of making video games, a hobby they had started engaging in one year prior. Dave Murry therefore associated with fellow engineer Joe Garguilo to found Evryware in 1980, with Barry joining the new company shortly thereafter. As their platform of choice, they set their eyes on the Heathkit H-89 (aka the Zenith Z-89), a 1979 computer with significant success among hobbyists and professionals, but no mass-market appeal, what with its two colors and lack of graphics beyond the default character set. Evryware released a number of space-related “fast action graphic games”. InfoWorld (11th of November 1982) wrote a positive review about them, even though the screenshots attached to the article scream “well-done arcade clone” – but then if you owned a Heahthkit you were presumably happy to have clones in the first place. I surmise that’s also why Dave Murry remembers this period as “successful” despite the lack of broad popularity of the Heathkit: as far as gaming was concerned, it was a small pond, but they were the only fish.

The Heathkit was a dead-end, and so Evryware moved to a new platform in 1983: the IBM PC, and of course this time they had flair. While Joe Garguilo focused on a software called Evrydiet: A Diet and Nutrition Guide, the brothers worked on a boxing game for Microsoft. When Microsoft reneged on the deal, Dave Murry called his acquaintance Roberta Williams of Sierra On-Line, and so the boxing game was eventually released as Sierra Championship Boxing, a simulation which included both real-time boxing matches and management of the athletes, in addition to a broad roster going from historical champions to a kangaroo and an alien.

After Sierra Championship Boxing, the brothers (sans Garguilo, who apparently moved to other ventures, though it is unclear if he is still co-owned the company) started working on a wargame of a new sort. As they explained in an interview to Orchun Kolcu [and I have to bless the Wayback machine for preserving the only interview of the brothers] :

“All the war games at the time were almost direct translations of board games with hex grids, dice and turn based play. After playing a few of these, we realized that the computer was capable of much more. The idea was to create the same experience that a general would have when leading his troops. You don’t take turns when fighting real battles so we replaced it with real time play. We also wanted to portray the personal aspect of war. Of watching your troops die in battle. That is why we included the zooms.”

The brothers did not make the first game portraying the personal aspect of war (Computer Ambush did it in 1980 and Field of Fire did it even better in 1984), nor are they fair in stating that the other wargames were about dice and turn-based play. However, they are right in that very few wargames allowed free movement unconstrained by a grid in 1984, and almost none would have been available to the brothers: Excalibur had a confidential release, Stonkers was only available on the British Spectrum and the other games without grid I can think of are all naval, from the decent Broadsides to the barely playable Ram! and the effectively unplayable CINCPAC.

As for the often repeated claim that Ancient Art of War was based on Sun Tzu’s eponymous book, the brothers qualified it: they only discovered Sun Tzu mid way through their project, just as they needed something to tie the game together. “It was just what we needed. We incorporated his philosophies into the game and wrote the manual in a style that was similar to his book.”

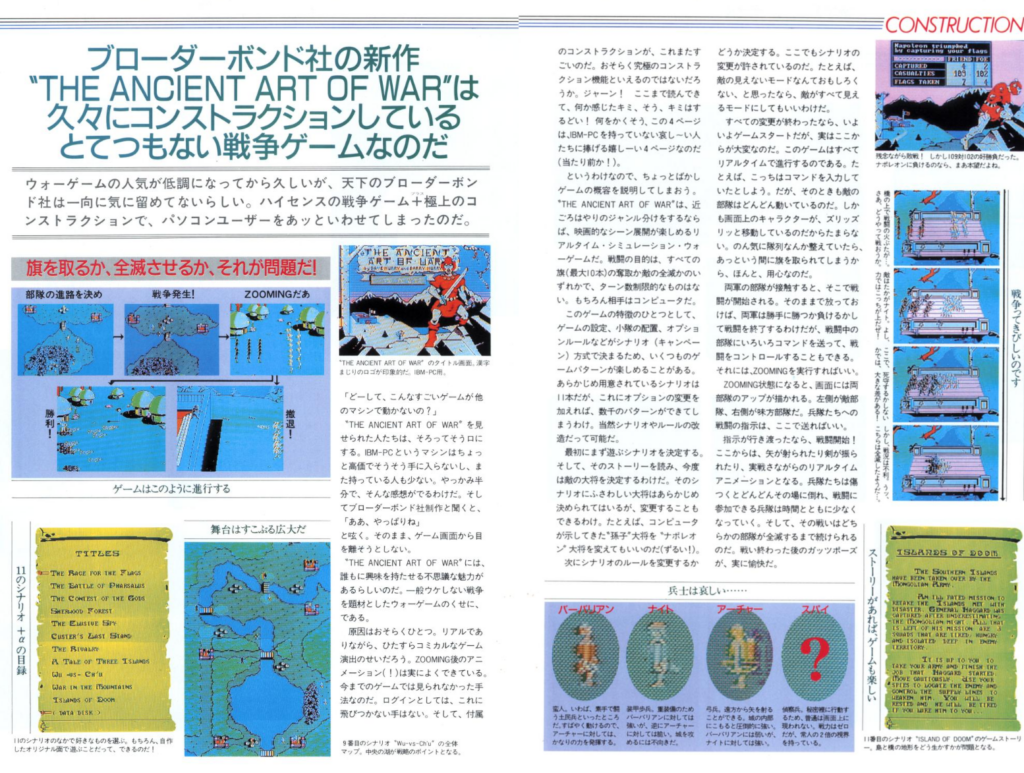

It is unclear why the brothers published their game through Brøderbund rather than Sierra On-Line. Most sites state that the game was released in 1984, and maybe it was indeed if you had privileged information on Brøderbund’s line-up, but for the rest of the world the game was announced during the Winter Consumer Show in Las Vegas (5th – 8th January 1985). Cathy Carlston of Brøderbund also explained to the bi-weekly PC Mag (8th of January, 1985): “We are just now releasing a PC package called The Ancient Art of War. It isn’t a wargame. but it is based on a Chinese book that established the art of military strategy and tactics.” This sentence is also a good example of Brøderbund’s marketing strategy: deny against all evidences that Ancient Art of War was a wargame – because wargames are dusty, boring and not mass market – and enhance its status by mentioning the prestigious little Chinese book. It certainly worked, and Ancient Art of War was wildly successful, receiving several ports and visually improved versions (Apple II, Mac, PC-88, PC-98, DOS-EGA, Amiga, Atari ST and even Amstrad CPC) until 1990.

Traits – Ancient Art of War is so different from any of the games I played before on this blog I don’t believe I can cover everything. I feel the game works because of a combination of three factors that no other game managed to have together before: it’s deep, it’s intuitive and it’s rewarding.

Depth first. Despite his visual simplicity, Ancient Art of War manages more parameters than most of the wargames I played: supply (“food”), recruitment (in forts), fatigue, fog of war, terrain. Players can merge or split their armies, change their speed (at the expense of fatigue, of course) or change their formation. Final layer on complexity: you can change some major rules in options (do forts provide food? can you recruit new soldiers? can you reasonably go through forests?…), which of course significantly alter the game. I don’t think any earlier game has a better combination of depth and customizability.

Playability then. Despite its depth, this is one of the simplest games to play: you immediately get a sense of terrain just by looking at it, unit icons change when units are fatigued, movement is drag-and-drop and all information on units (formation, supply, etc) is one keyboard press away. As for understanding the game balance, no need to spend hours analyzing a combat result table – you can immediately get a grasp of it by looking at a combat. Even terrain effects are diegetic: forests and bridges are narrow, allowing archers to shoot at massed enemies and land more arrows.

Finally, the game is rewarding: the map is beautiful to look at, and your armies (if not exhausted) react immediately to your orders. But of course, the most obviously rewarding part of the game are the battles: 40+ years later, they still have a je-ne-sais-quoi that modern games don’t. I like to see the randomized background, arrows fly over the battlefield, friends and foes alike fall to the ground during a brutal melee and the final look of the battlefield, with the survivor rejoicing over bodies littering the ground. There are other – less obvious – rewarding aspects of the game: even with fog of war it is easy to set a plan of motion and observe the result: if you see an enemy army, you can look at its composition, fatigue or food level. Campaigns are won or lost quickly and usually without downtime and you don’t have those boring moments where you know you’ve won – or lost – but the campaign still lingers on. To an extent, Ancient Art of War is a rare early example of “die and retry” in wargaming.

Is the game perfect? Well, of course not. The game has evident issues when you play it. Some of them I would not even mention for a lesser game, but I need to future-proof this review for future articles about even better games. Starting with the nitpicks:

- the pointer is too slow to move, so if you don’t slow the game a battle may “auto-resolve” before you have the time to zoom on it – frustrating when it happens,

- Combats have a lot of options, but really the only orders you will give outside of a siege are “attack” and “retreat”,

- Similarly, there are only 3 of the default formations that I find useful – though at least the other formations create some diversity when the computer uses them.

The real issue with Ancient Art of War is the AI, which often does absolutely suicidal moves, like attacking forts without archers or advancing toward your flag even though they are absolutely out of food. I have never seen the computer retreat when facing superior forces, its only two movement settings are “ignore your army” and “aggressively move toward your army”. This is a huge problem in a solitaire game, and the weakness of the AI really constrains the scenario design: many scenarios rely on giving the AI an overwhelming force or a chance to win immediately, for instance by only giving you one flag immediately under threat.

Speaking of scenarios, Ancient Art of War offers 11 scenarios, but around a third of those are stale puzzle scenarios (eg “race the flag”). This leaves around 8 “real” scenarios… which is more than what any other wargame of the era except Field of Fire offered. Those 8 scenarios are generally pretty good, but if that’s not enough, then you can alter the way the scenarios are played (changes in supply rules change the vibe of a scenario). Additionally, the 8 different AI opponents are different enough in tactics and bonus that each offer a somewhat different playing experience: Athena beelines for your armies, Alexander sticks to plains if he can, Geronimo ignores terrain effects and moves fast. To my knowledge, Ancient Art of War is the first game allowing you to choose among different AI opponents with different behaviors.

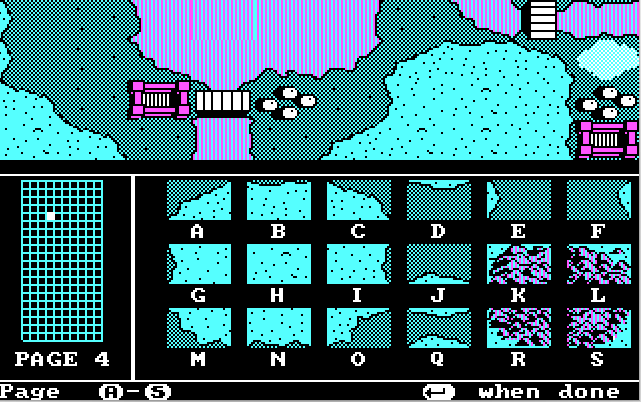

If that’s still not enough – and even if it is – the game comes from a really easy to use editor. The game is really made of simple bricks, but there are a lot of ways to assemble them, and so I believe it is quite possible to make solid scenarios that don’t really force unbalance to be interesting – I like to think that the two scenarios I made for the DataDrivenGamer proved that.

Did I make interesting decisions? Yes, particularly at the beginning of a campaign. Once the typical initial crisis is passed, the game is mostly about the most time-efficient way to win the battle (but it’s still fun!)

Final rating: ☆☆☆☆. I had only one problem when rating Ancient Art of War: the qualitative difference between The Ancient art of War and my previous favourite Reach for the Stars is so large that I pondered giving five stars to the former. However, there is a much smaller qualitative difference between Reach for the Stars and War in Russia, and so I instead decided to downgrade Reach for the Stars, which as good as it was still plays like an old game; add mouse control, a few more unit types and a graphic update to Ancient Art of War and you could absolutely release it as an indie game on Steam.

Ranking at the time of review: 1/180. Just like Eastern Front 1941 3 years before, Ancient Art of War set a new standard for wargames – and I already know that most of the 1985 games will fall short of it.

Reception

Giving the Ancient Art of War the first rank and downgrading the former best game may sound like nostalgia speaking, but the contemporary reviews were for once both numerous and absolutely in sync that this was the best wargame of the market. I can’t quote all the reviews, but let’s say for instance that in the case of Computer Gaming World, editor Russell Sipe himself penned an article (May 1985) explaining that with The Ancient Art of War (and GATO), Computer Gaming World now had to cover the IBM PC. Moving to the review of The Ancient Art of War itself, Sipe made a long list of everything the game did right, adding only two negative aspects: a predictable mention of the lack of multiplayer and a bizarre complaint that the game did not feature artillery and so Sipe could not create a Waterloo scenario. Nonetheless, the conclusion is pretty clear:

“Wargamers are constantly seeking the ultimate wargame. But, if they really admit it, what they demand from such a wargame is impossible to deliver. As for me, TAAW meets a lot of my expectations of an ultimate wargame and if it doesn’t meet them all, it certainly comes closer than most. Great game.”

As I said, this review is echoed all across the gaming press and beyond, with for instance Jerry Pournelle simply stating in February 1986 “the game of the month is Broderbund’s The Ancient Art of War, which [my kids] say (and I confirm from my own experience) is about the best strategic computer war game they’ve encountered“.

Browsing through the reviews of Computer Entertainer, MacUser, Creative Computing, Family Computing and MacWorld – all of them exceptional -the reviewers were most impressed by the visuals (the battles, of course, were always highly praised) and by how easy it was to get into, making it a game really for everyone. Most mentioned the coolness of choosing among several AI opponents, and none failed to mention the editor, many expecting the game to stay fresh for many years – I reckon they were correct.

Ancient Art of War had similar success in France. It was reviewed by Tilt at the same time as 35 wargames (December 1986), and ends as the clear leader of the pack: it is the only game with 6 stars in” graphics“, the only game with 6 stars in “realism” and receives the maximum of 5 stars in “interest“: “Fascinating from start to finish”. Similarly, Jeux & Strategie has a special issue in 1986 about all the video games available in France, and Ancient Art of War is “unrivaled and inexhaustible“, leaving every other wargame in the dust; actually it is one of the three games of any genre with a perfect score, along with Choplifter and, err, Cauldron? In any case, Jeux & Stratégie describes the Ancient Art of War as the first wargame designed for a computer.

The long-tail of releases of versions of Ancient Art of War (the EGA version and the Amstrad CPC port) triggered another wave of reviews in 1989-1990. The game had aged a bit, so some reviews were barely “good”, though a lot remained excellent. It’s also at this moment that Evan Brooks finally mentions the game (October 1990, CGW) in his review of all pre-modern wargames. He gives the Ancient art of War 3 stars – commenting : ” A tactical rendition of various “battles,” this product is an enjoyable game, but any relation to history (or the book of the same title by Sun Tsu) is purely coincidental. Some of the scenarios are unbalanced, but the game is easy to learn and has its own scenario editor/ generator.”

I could not find how many units the Ancient Art of War sold, but it was obviously huge – a 6-digit number for sure. Evryware would release the sequel the Ancient Art of War at Sea in 1987 which is in my opinion an even better game. Evryware also released in the early 2000 the free Ancient Art of War 2, which removed the tactical battles and ended up pretty terrible in my opinion. This did not ruin the Ancient Art of War legacy, which is often mentioned as either the first RTS (which we know it isn’t) or an ancestor to Total War (which it may very well be). As for me, when I launched this blog my objective was to at least reach Ancient Art of War. Well, now I did, just as various real-life events drastically reduced the time I have to update it. I will probably continue, but I am afraid updates will be less frequent then they were one year ago. After all, I need to at least cover Kampfgruppe, the game that consistently beat Ancient Art of War in the various Computer Gaming World rankings.