[ZX81, Sinclair User]

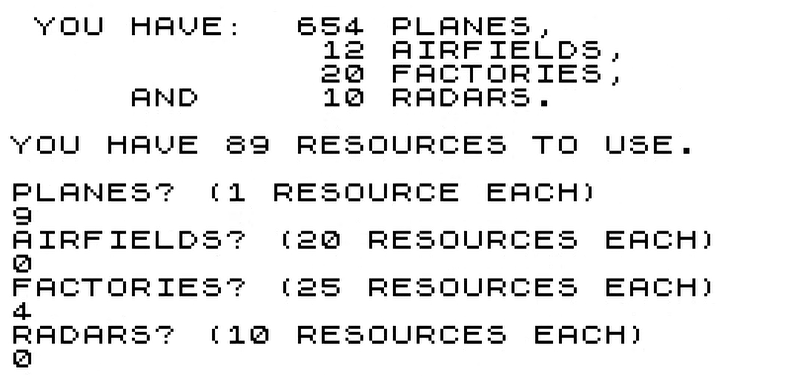

Sinclair User was launched in early 1982 (first issue: April 1982) and by mid-1984 it had offered possibly more than one hundred type-in games – none of which were wargames, except if you count a computer version of Battleship. In July 1984, Sinclair User included the first and only game that SpectrumComputing.co.uk tagged as a wargame: Luftwaffe. The theme was sure to warm the hearts of the British: the Battle of Britain.

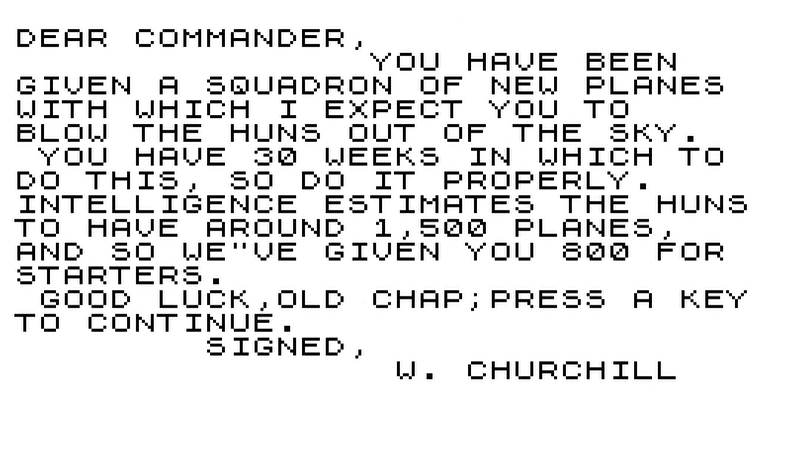

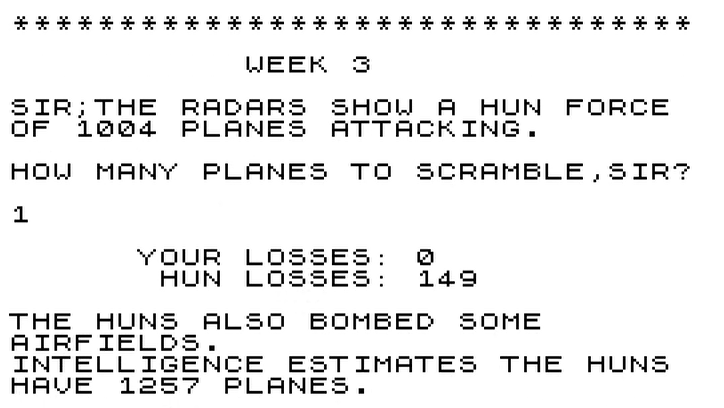

Every week, the Germans attack with some of their planes, and I am asked how many planes I want to scramble against them. Scrambling a lot of planes can be incredibly costly:

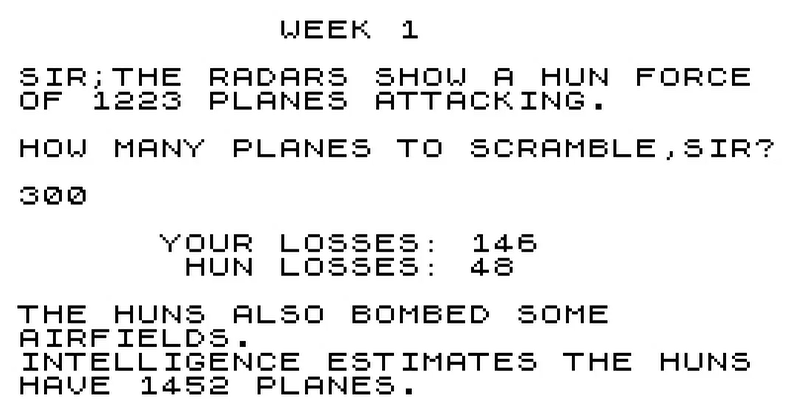

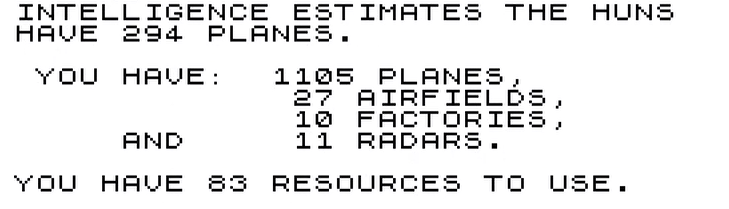

After the battle, I receive between 50 to 150 resource points (completely random) that I can allocate between planes, airfields, factories and radars:

- Airfields determine how many planes I can send at the same time (50 per airfield),

- Factories determine the maximum amount of planes I can build in any turn (20 per factory),

- Radars tell me how many enemy planes are attacking – but I have all the information I need with only 3 radars,

Given I start with 15 airfields, 20 factories and 10 radars, and that my loss of ground assets is proportional to how many of them I have, I will not be building a lot of them. In this session, I only built planes, and a few airfields at the end.

I wish I could tell you there is more to this game but… no there’s not. The same sequence of questions repeats: How many planes do you send? What do you build?

There are no tactics in this game – once you understand how it works it is purely based on chance. Do you remember the disaster in the first week, where I almost lost 150 planes in combat? Well, here is what happened in week 4:

Yes, I sent one guy alone against more than one thousand German planes and he shot down 149 of them before returning to base. I like to think he ran out of ammo.

This is because the game does not take into account the number of planes you have to determine German losses, but rather the number of planes the Germans have – and the same for your own losses. More specifically, the game compares the number of planes on both sides, and based on this, it destroys:

- Randomly between 50% and 100% of the planes of the German or British side, if that side is outnumbered by a factor of two – there is a caveat here that I will explain later.

- Randomly between 0% and 50% of the planes of the German or British side, if this side is outnumbered by a factor of less than two,

- Randomly between 0% and 25% of the planes of the German or British side otherwise, except if the British outnumber the Germans by a factor of two, in which case the British are punished for using too many planes by losing 50% to 100% of them!

This means that if you cannot outnumber the enemy planes, the best choice is to send only one plane: you can destroy as much as 25% of the enemy air force, and at worst you lose one plane.

At some point, because almost all your resources are funnelled toward making more planes, you will massively outnumber the Germans in terms of available planes:

That’s when you should pivot to sending twice as many planes as the Germans to finish them off quickly, even at the cost of a lot more losses on your own side. When the Germans have 30 planes left or fewer, the Battle of Britain is won…

… except I did not win, because there is an oversight in the code, lines 500 to 540. I copied it below, replacing the variables “D” and “C” by “British_Planes” and “German_Planes” respectively. E corresponds to how the losses will be calculated.

500 IF British_Planes >= 2*German_Planes THEN LET E=1 510 IF British_Planes <= German_Planes/2 THEN LET E=2 520 IF British_Planes < German_Planes THEN LET E=3 530 IF British_Planes > German_Planes THEN LET E=4 540 IF British_Planes = German_Planes THEN LET E=5

Critically, the program goes through the five lines in order before calculating the final losses, which means that the last line that qualifies is the one used to calculate the final losses – and lines 520 and 530 always apply when lines 500 or 510 apply. This means that no losses are ever calculated as if a side was outnumbering the other one at a 2:1 ratio and losses will never exceed 50% of the planes involved. That’s why the plane I sent alone always survived its battle.

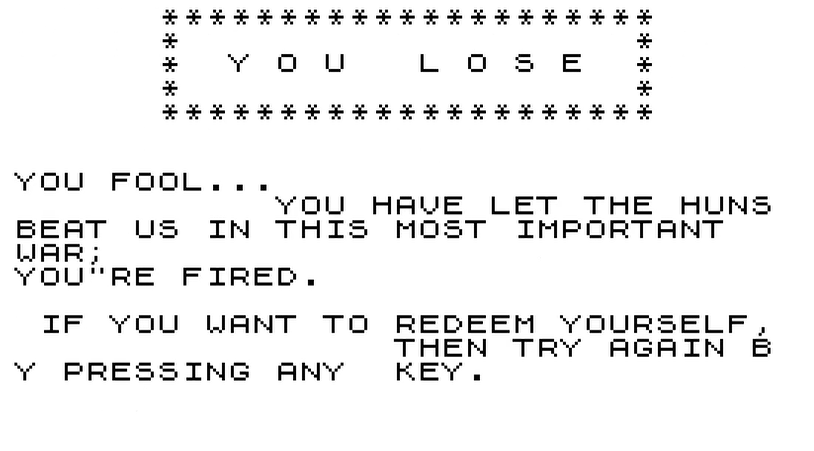

This makes the game effectively impossible as the Germans gain 30 new planes every week, and you need to bring them below 30, and henceforth:

Luftwaffe is Jason Currie’s only game. You can find its source code here or play it here – bugs included. It is what I call an “allocation game”: a game where the player allocates some numbers and then receives a highly randomized output based on that. This subgenre flourished during the mainframe era (the venerable Civil War in 1968 was one) but by 1980 it was already obsolete, except as type-in games more useful as learning experiences than as, well, games. I don’t consider Luftwaffe a wargame, hence its BRIEF status. If I had ranked it, it would have been in my bottom 5%, bug or not.

Next, we will return to everyone’s favourite gaming platform: the Coco, with everyone’s favourite battle: Guadalcanal!

Also: Merry Christmas everyone and thank you for following this blog!

8 Comments

Hmm, I’d consider King of Dragon Pass an “allocation game” but it’s an amazing game 😀 Merry Christmas! I greatly enjoy your blog, really takes me back.

If I had to put King of Dragon Pass in the wargame category, then it would be either a Grand Strategy game (diplomacy, warfare, “human management”, economic development, even religion) or a “City Strategy” game like Supreme Ruler [1982] or Warlords. Probably more the former.

Allocation games are unidimensional and typically their “rounds” are loosely connected. It is also a “catch-all” category for games that are not deep enough to be full-fledged wargames (or anything , really). The gameplay is about finding the optimal allocation and then hoping for the best with the RNG.

King of Dragon Pass is wonderful, I have it on my iPad. Glorious!

An interesting little game, but much too simple.

The part where you put a single fighter on defence but the enemy loses 149 planes actually makes some sense, if you send out a raid a portion of the planes involved will always end up falling to accidents, navigation errors, flak, etc.

Punishing the player for using too many planes also makes some sense if we imagine that you’re focusing a lot of planes against the same raids leading to confusion, friendly fire, etc, but it should be a small percentage instead of 50% or 100%.

It looks like the game could be improved with some little tweaks, even it would always be a simplistic little BASIC thing, you could add weather which could increase the losses for both sides and add a little variation to the turns, do you stay down and save your fighters during a bad weather day or do you think that you can’t afford the damage of this raid and send them up anyway?

Thinking about raid damage, raids could have a target (factories, airfields, radars) that would take the brunt of the damage and would change every few turns, either because the player doesn’t have many of those assets left or randomly because Hitler or Goering decided to have a tantrum and demanded a campaign against this or that.

Radar could help here, the better the odds the better the chances that the game will display the enemy’s choice of target to the player, and we could put in a chance that the enemy will sneak through unopposed and do a catastrophic level of damage, bad coverage makes this a possibility, good coverage makes the chances of this minimal.

We could also give the player two or three chances to allocate fighters per turn, sending the fighters early limits the raid’s damage, sending them late inflicts more losses on the enemy since they catch planes low on fuel.

Oops, looks I got carried away and started overthinking this way too much…

But this was the beauty of type-in games. You got a working base and some on-field experience in writing programs (copying the list was not trivial on those computers), then you could adjust/expand the program as you saw fit. A lot of European developers started their trade as teenagers improving these barebone listings.

A little late Merry Christmas to you, Scribe, and thank you for creating this blog! 🙂

Merry Christmas, or should I say fröhliche weihnachten as I’m now under the jackboot…

Dodgy logic and the ordering of IFs is a common cause of horrible errors…

Never have so much owed so many to so few lines of code

Also that one pilot was clearly Richard Sharpe played by Sean Bean.

And late belated Christmas to you. Thanks for an always great read. About half of the early Spectrygames, certainly by CCS and Lothlorien, we’re allocation games like this.