[Richard Bodley-Scott, TRS-80]

In the Monastery of St Peter in Northumbria, around 720 AD :

- Father Bede, we must find a common name to describe all the people who settled in Britain during and after the 5th century !

- I propose…

< silence >

Wait for it !

< suspenseful silence >

…“the Anglo-Saxons” !

< wild applause > - But what about the Jutes ?

- Let’s pretend they only occupied the Island of Man and everyone will soon forget about them.

There are at least 3 King Arthur :

- The first one (the “historical” Arthur) is the possibly fictional 6th century Romano-British (aka “Welsh”) King or war chief mentioned in some later chronicles, but not by the contemporary Gildas. This is a bit of a problem for the proponents of the thesis of the historical Arthur, because Gildas loved discussing the various Kings of Wales, usually rating them 1-star “would not be ruled by again” but Gildas may have missed him or mentioned him under another name,

- The second (the “Romance Arthur”) is based on Geoffrey of Monmouth and then Chrétien de Troyes’s 12th century fan-fics. They added all modern recognizable elements to the Arthurian legend : Merlin, the Knights of the Round Table, the Grail, Lancelot, and even (especially with Chrétien de Troyes) King Arthur not doing so much after all and letting someone else solve his kingdom’s many issues, Lord British-style. Because you know what’s more fun than managing a kingdom ? Love triangles !

Also, who brought a lion in the meeting room ? - Finally, there is the modern Arthur as rediscovered and reinterpreted starting from the 19th century. The sub-Roman era being neither well-known nor easy to grasp (“so the Welsh are actually Romans, but not part of the Roman Empire anymore.”), most of the Arthurian modern stories use the cultural codes and technology of the Age of Chivalry. Similarly, the Knights of the Round Table received were drastically downsized to only a handful of bankable characters. As for King Arthur, he became a brand name ; if your story includes dragons or early Britain, or both, then you can probably throw King Arthur in there for free and the audience has a name they can recognize. Of course, there have been some attempts in mass media to describe a historical Arthur (eg the movie King Arthur in 2004), but I don’t know any that was really successful.

Richard Bodley-Scott’s second game (after Emperor) is about the first King Arthur. There is no dragon, no Graal and no Excalibur, just hordes of Angles, Saxons and Jutes to push back to the sea, or at least back to their landing areas.

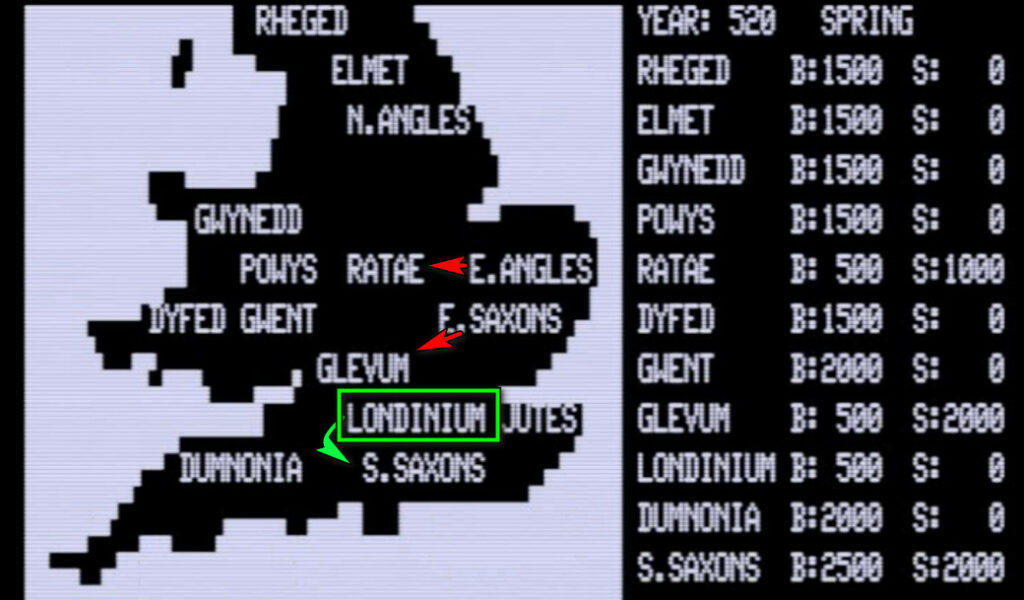

The game starts in 520 AD, and opens on a map of England :

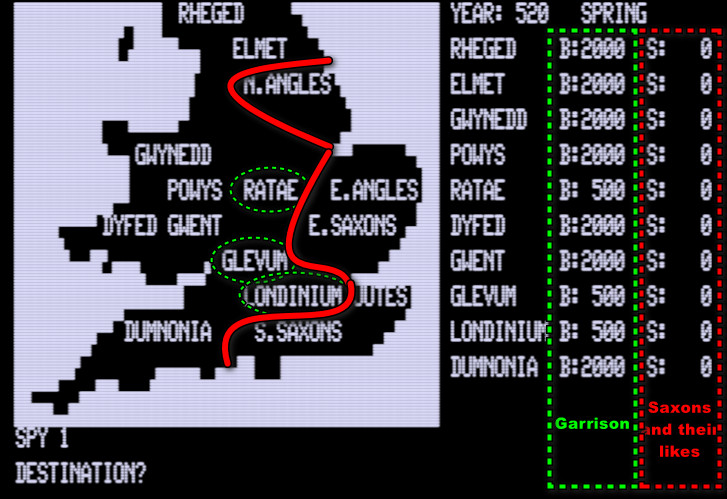

England is divided in two :

- the larger part still held by the Romano-British, with all their petty Kingdoms in the South-West, West and North, and 3 Roman towns in the middle : Londinium [London], Glevum [Gloucester] and Ratae [Leicester],

- the Southern and Eastern coastlines are held by the Angles, the Saxons and the Jutes, which I will collectively call the Anglo-Saxons because no one cares about the Jutes, not even the game.

As I am King Arthur and not some real historical leader who has to care about minute Welsh kingdom squabbles, I can call every turn 500 men from each of the latter (the cities don’t contribute) and use them for the year. But before that I can send spies – initially 3 by turn – to check what my new neighbors are doing.

- I send one to the Southern Saxons, who settled in modern Sussex, a region that by a funny coincidence sounds like a short name for “Southern Saxons”. In any event, my spy reports they have 2 000 men not doing much,

- I send another to the Jutes, 2 500 men busy doing nothing,

- Finally, my last spy is sent to the Eastern Saxons, who settled in – what were the odds – modern Essex. I mean, what’s next ? Wessex and Nossex ?

In any case, my spy is caught and killed. I receive a new spy every year so he will be replaced easily.

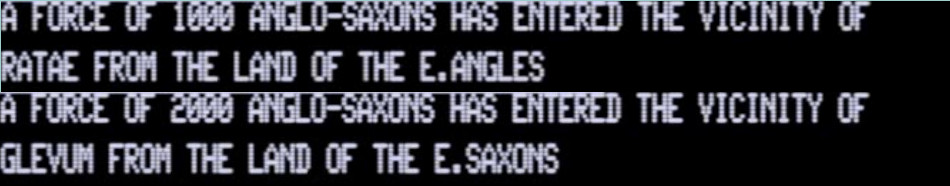

Well, my plan is to quickly mop-up the invaders from the South, because Londinium and Glevum are hard to defend and if they fall there is nothing I can easily do for Dumnonia. I gather the Welsh army in Londonium – only 2 500 men this year because Gwent and Dumnonia did not send anyone. Meanwile, the Eastern Saxons and the Eastern Angles (from, er, modern East Anglia) fall on Ratae and Glevum.

I could easily chase the Anglo-Saxons from those two cities, especially since I have 2 movements by turn (one in Spring, one in Autumn), but those cities should be easy to retake later on. Instead, I stick to the plan and fall on the Southern Saxons. If I crush them in their home territory, I can stop worrying about existing South Saxons, but more importantly their migration from Saxony will be slowed down. No one wants to join a project when the alumni testimonials are all variations of “I was stabbed in the face and my family sold to slavery“.

Unfortunately, the South Saxons hold the line. In King Arthur, soldiers only die if a battle is lost, so my army remains 2 500-men strong and the South Saxons are still 2000-men strong.

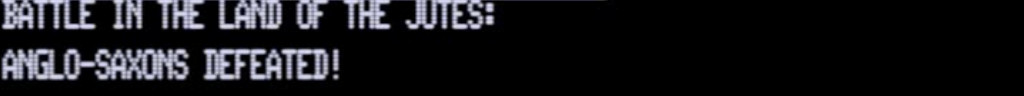

I ignore them and move into the Jute territory in Autumn, kill all the warriors and hopefully also slay Hengist and Horsa, preventing historiographic debates from ever happening in the future.

Glevum falls, while Ratae is still resisting the Angles.

At the end of the year, all the soldiers return to their homes.

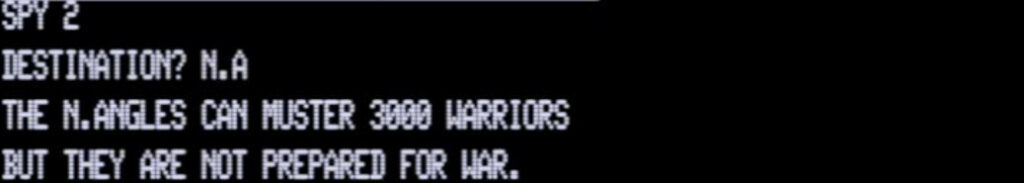

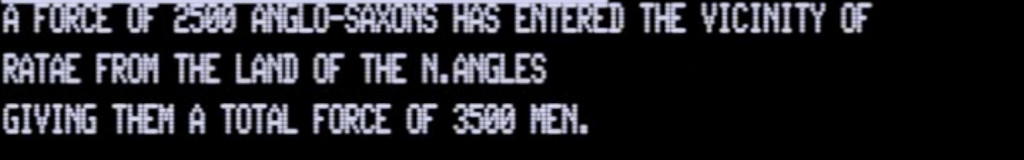

The year is now 521. My spies report among others that the North Angles are still accumulating men :

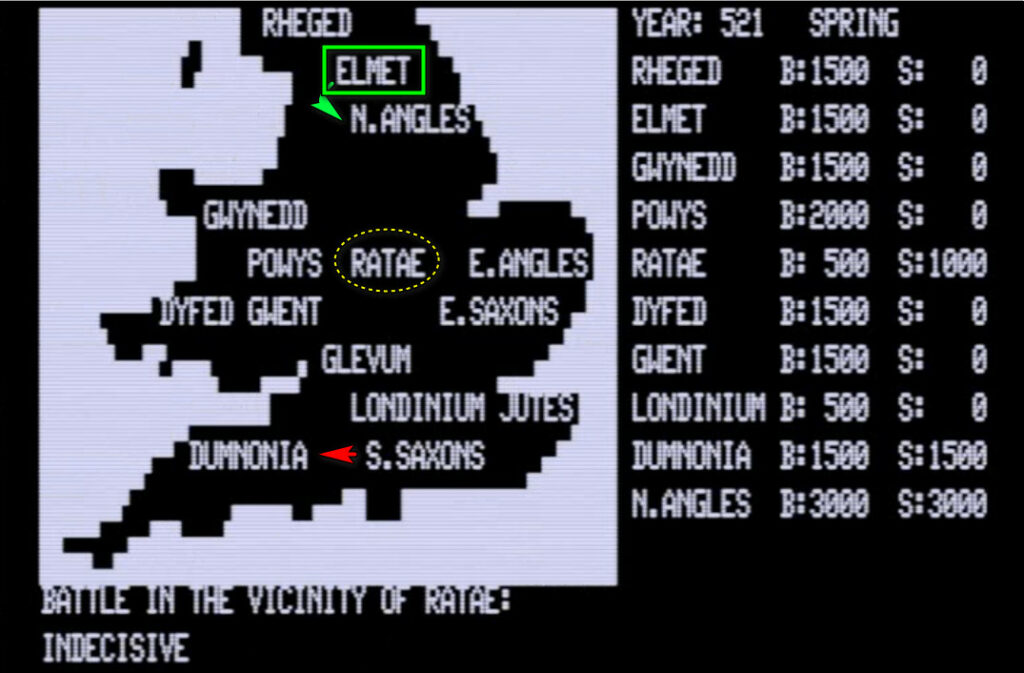

The maximum size of my war-host is 3 500 men (500 men x 7 Romano-British kingdoms) so I need to strike now before they reach an unstoppable size. I gather my forces in Elmet, ready to march South.

Unfortunately, Powys does not send men so the best I can achieve is parity with the Northern Angles – the battle is undecisive. As I know from my spies that there are only 2 500 men in East Anglia, so I move there in Autumn, destroying the Anglo-Saxon army there. Meanwhile, Ratae finally falls.

In 522, the Anglo-Saxons don’t attack, instead choosing to reinforce their newly acquired cities.

Starting in Londinium, I use the opportunity to break the siege of Dumnonia, before raiding the South Saxons’ home base and destroying the thousand or so men still there. The following year, I fend off an attack on Gwent, before counter-attacking and retaking Glevum, though I lose Londinium the same year. From Glevum, I raid Essex in 524.

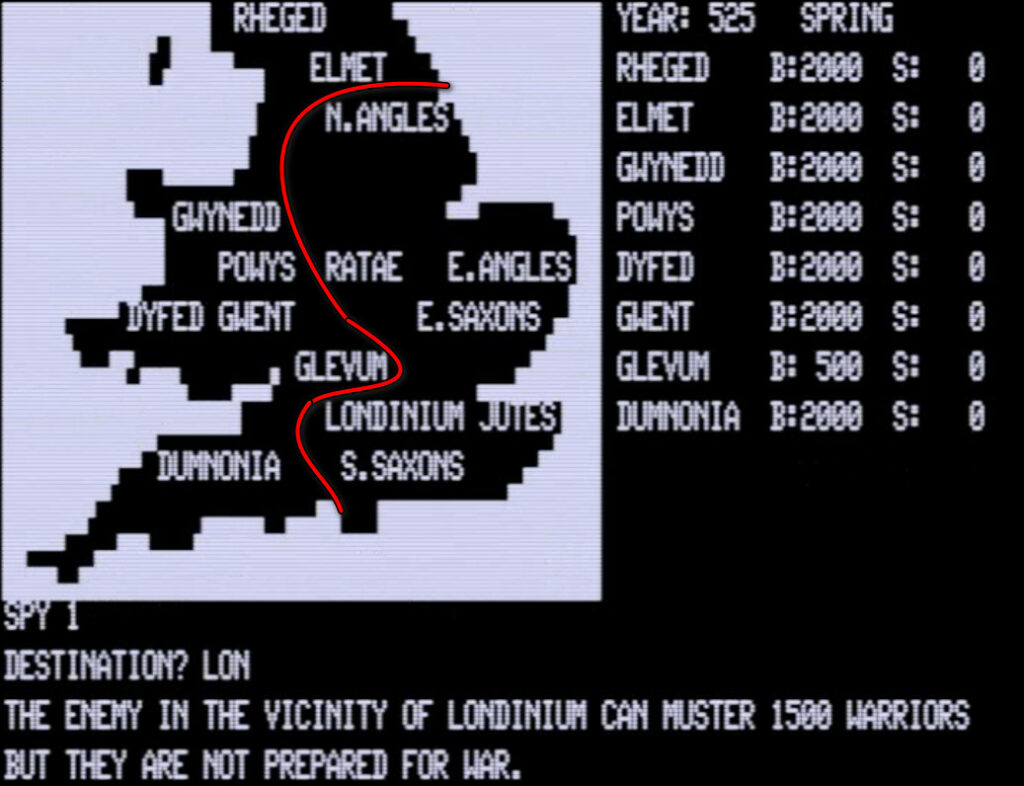

At the beginning of 525, the situation is quite good. I lost Ratae and Londinium, but still have all the kingdoms that contribute to the war host. Meanwhile, the Eastern Saxons are destroyed and I know from my spies that the Southern Saxons and the Jutes are still recovering.

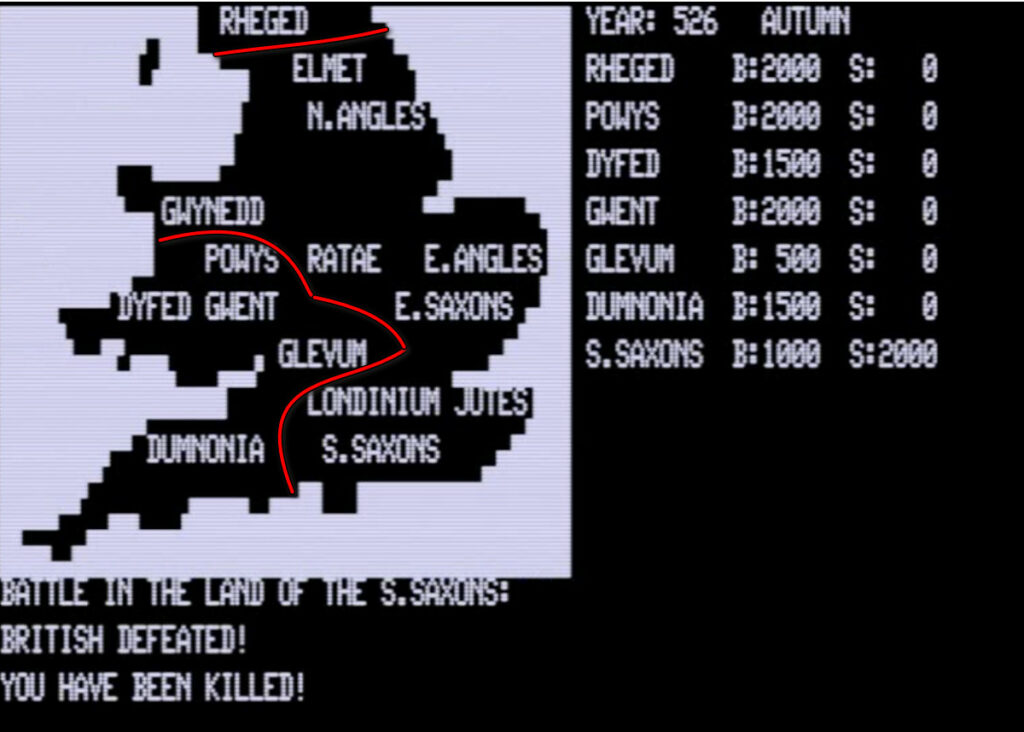

Unfortunately, the situation suddenly turns sour in 525. I make the strategic mistake of gathering my war host in Powys instead of either Gwynedd, Gwent or Glevum. From Powys, the only Anglo-Saxon territory I can attack is Ratae, but the Saxons reinforce it, bringing the garrison to 3 000 men. This could have been manageable if Gwent and Dyfed had not refused to send reinforcements this turn – this means I have only 2 500 men ready to attack – and I don’t want to lose a battle because I can get personally killed, which is an instant game over.

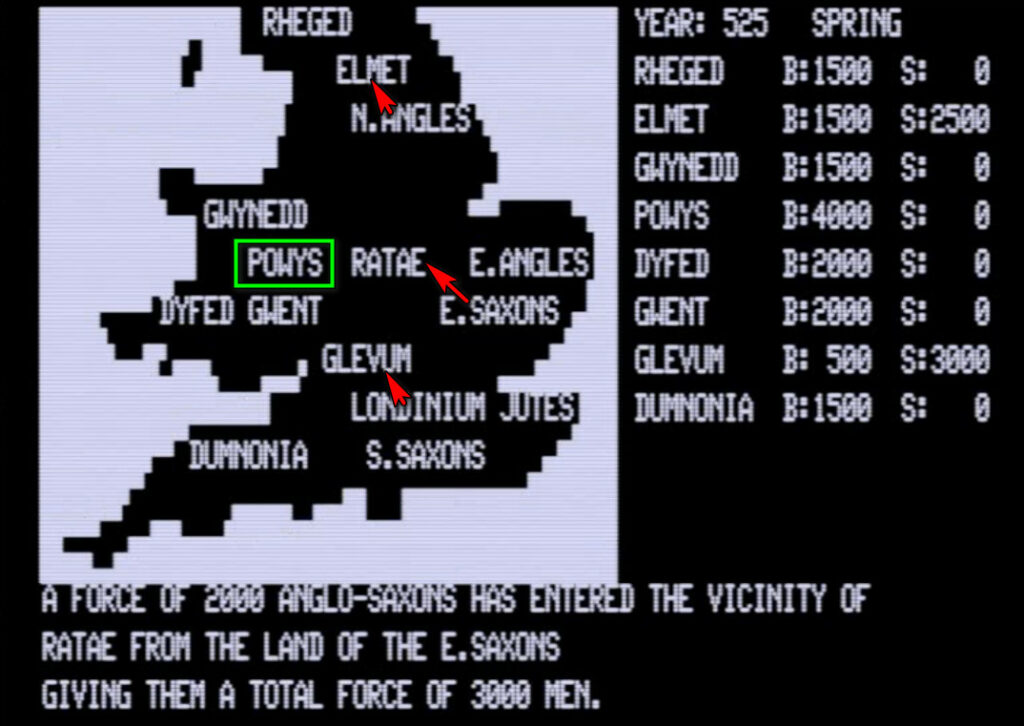

Meanwhile, the Angles attack Elmet and whoever is in Londinium moves to Glevum, and from Powys I cannot relieve the garrison. By the time I arrive, it is too late, and Elmet is lost.

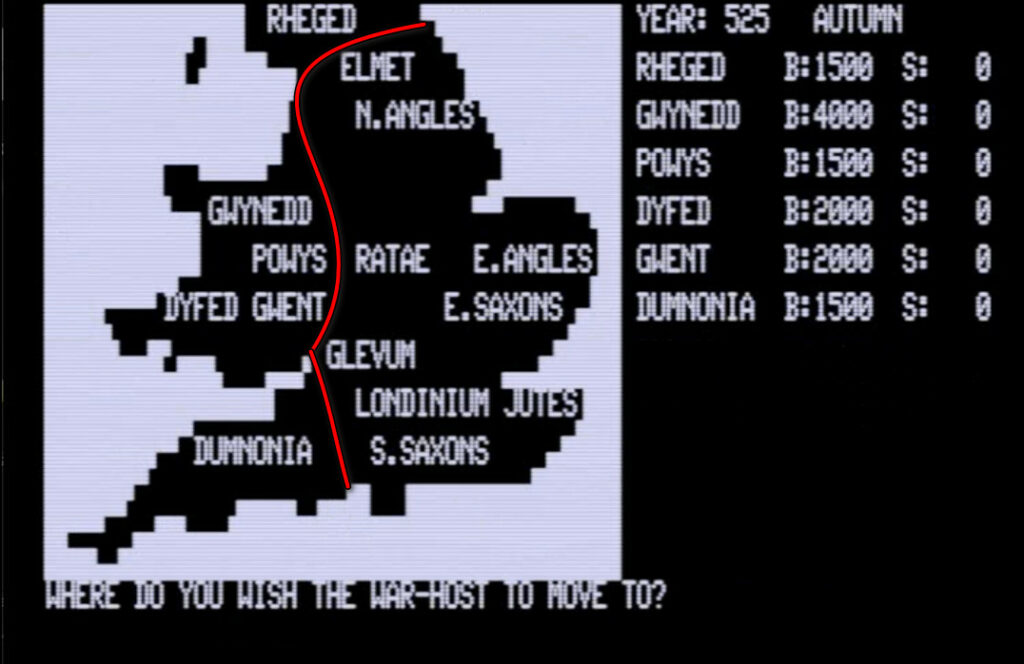

Losing Elmet reduces my maximum mustering capacity by 500, and I also lose access this turn to both Dumnonia and Rheged. I am still able to muster from them, but if they are attacked they will be on their own :

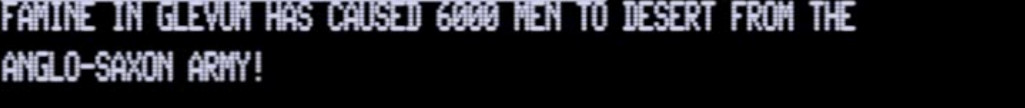

I improve my situation somehow in Autumn thanks to a bug. My men move from Gwynedd to Elmet, and even though they don’t manage to chase the Angles the game considers that since I have men in Elmet, the Kingdom is still mine as it resets the situation at the beginning of 526 – so suddenly I have a garrison of 2 000 men in Elmet again. These men are immediately reinforced by a new war host in 526, and the Anglo-Saxons are destroyed. After that, I make sure to nip “North Anglia” in the bud by crushing the few men the invaders had left behind. Meanwhile, the Anglo-Saxons, and even the Jutes at this point, accumulate massive forces in Glevum and Londinium.

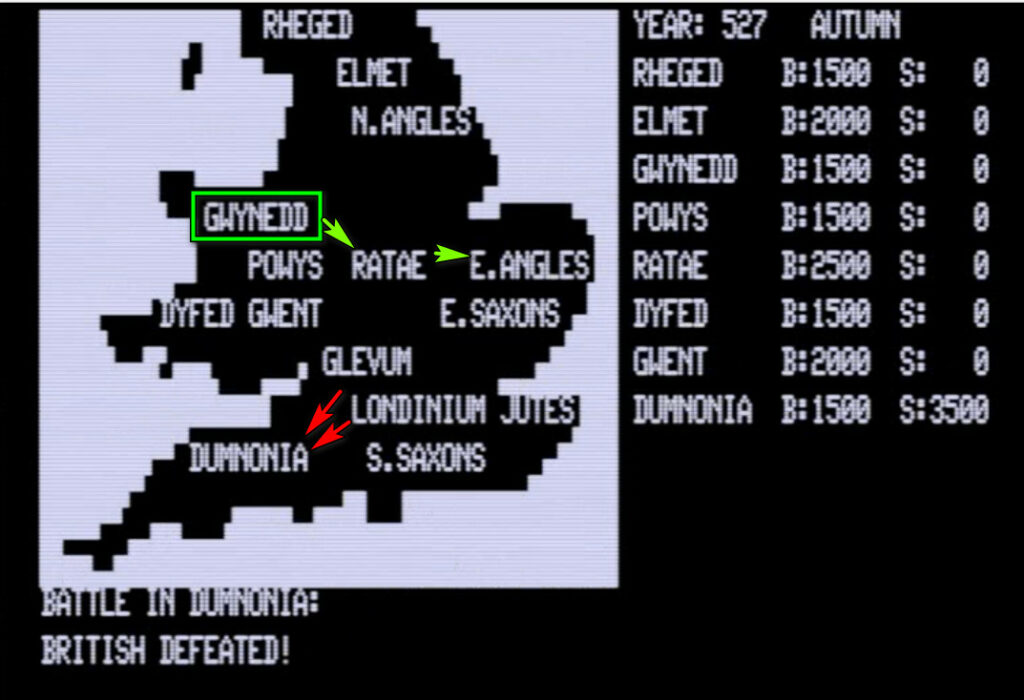

In 527 the gathered invaders strike Dumnonia, and there is nothing I can do. I liberate Ratae and vent my frustration on the Eastern Angles. With both Angle home bases burned down, it looks like the chroniclers and historians are going to talk about the Juto-Saxons after all. It does not roll off the tongue quite as well.

The Angles may be defeated, but in the South, the Juto-Saxons consolidate their forces in one massive army that can storm pretty much anything I have.

Is it the end of independant Wales ?

No.

The pattern repeats until the end of the game. The Juto-Saxons regroup massive forces in Glevum and Londinium, but these are so big that they are mostly lost to desertion or famine, and they don’t push any further. Even the invaders in Essex send their men to whittle away in the central cities rather than toward Ratae. Meanwhile, I cannot attack with my reduced war host (the men from Dumnonia are missing), but I can keep the Angles suppressed.

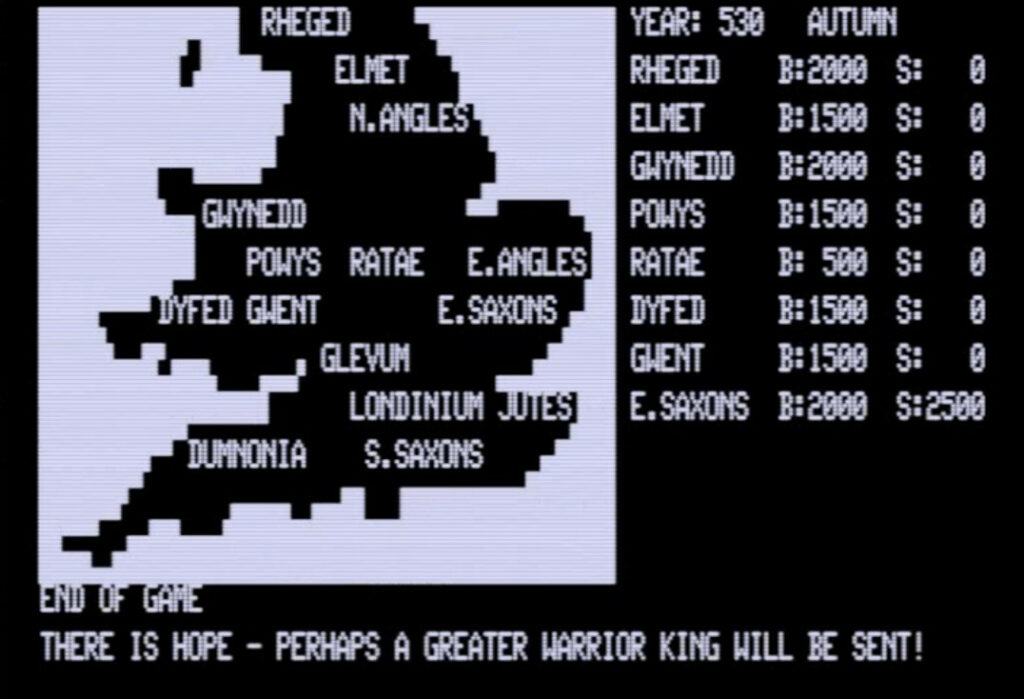

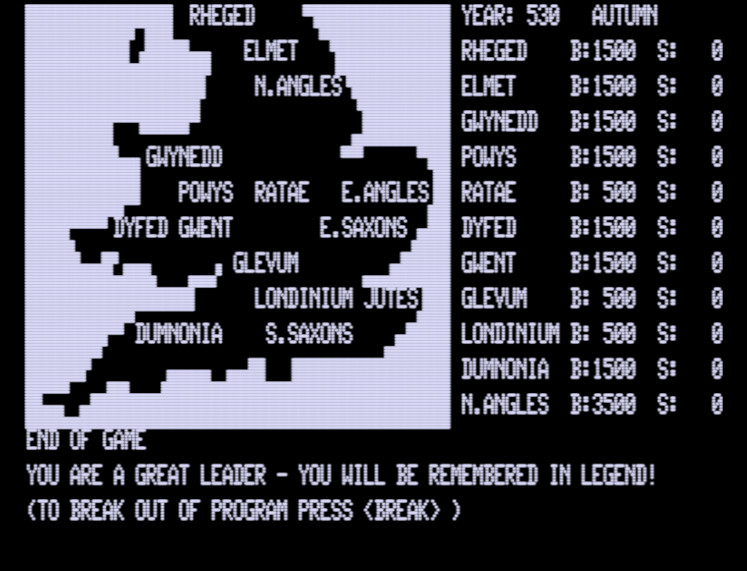

In 530, the game ends – and my King Arthur did not impress the game :

After such a failure, it is no wonder that King Arthur’s spin doctors pretended that the Saxons were never the real focus and that what people should really care about is finding the Graal and slaying Dragons.

Rating & Review

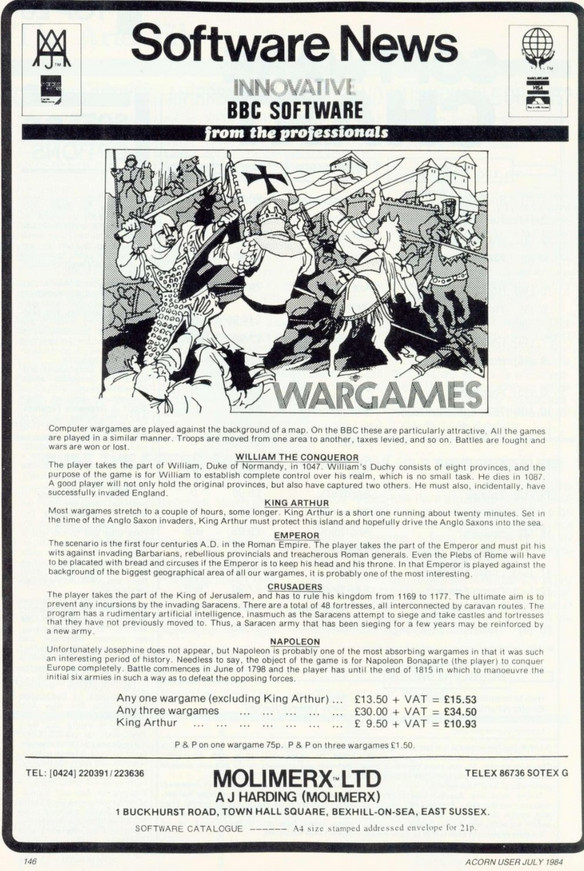

King Arthur by Richard Bodley-Scott, published by Molimerx, UK

First release : 1981 on TRS-80

Tested on : TRS-80 emulator (TRS-80GP)

Total time tested : 2 hours

Average duration of a campaign: 15 minutes

Complexity: Trivial (0/5)

Would recommend to a modern player : No

Would recommend to a designer : No

Final Rating: Obsolete

Ranking at the time of review : 31/64

I have very little information on King Arthur, the second game (after Emperor) of Richard Bodley-Scott. Bodley-Scott told me he chose this theme because it was well-suited to recycle the system of Emperor. I also found out that the game was ported in 1984 or earlier on BBC Micro from its initial TRS-80 1981 release, but that BBC Micro port is lost.

King Arthur is indisputably a wargame, and as such it deserves a full review, but I believe I showcased everything the game has to offer in the AAR, so I will be quick about it :

A. Immersion

I give points for the original theme, I don’t think I will see many games about sub-Roman England, so I had to use all the jokes I had on the topic in one go.

Rating : Very poor

B. UI, Clarity of Rules and Outcome

My only complaint is that it is not clear which region can be reached from which region. Apart from that, the game is easy to play, though that’s hardly an achievement given how simple it is.

Rating : Average

C. Systems

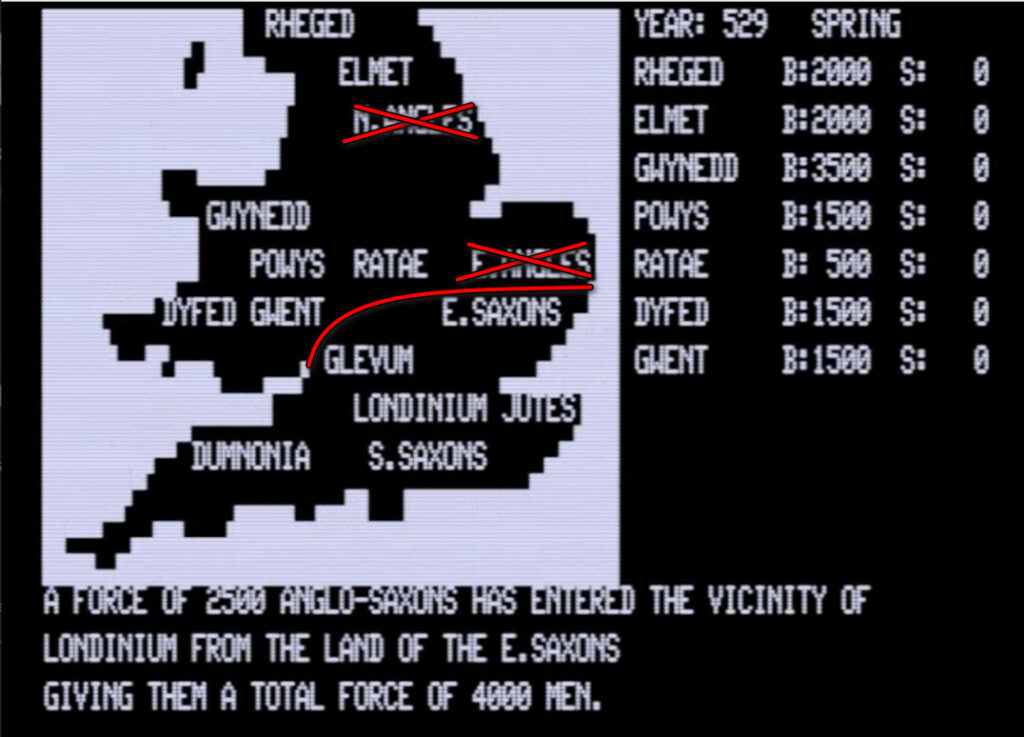

Bodley-Scott described the game to me as “whack-a-mole” and it is indeed an appropriate description. A typical turn always go through the same phases :

- The player sends spies in different areas to count the invaders and check whether they are going to move that turn, provided he (or she) is not killed,

- The player musters their force in an area free of Anglo-Saxons – each petty Kingdom contributes 500 men, though randomly some will not send anything,

Meanwhile, the Anglo-Saxons who decided to move invade one neighbouring territory with some but not all their available troops, - The player can move once,

- Battles are solved, with only 3 possible results :

- The battle is indecisive, nothing happens,

- The Anglo-Saxons win, all the British are destroyed,

- The Anglo-Saxons lose, they are all destroyed,

In general, the British army when led by King Arthur seems a bit better than the Anglo-Saxons armies, and beats more often than not a force of the same size. On the other hand, if the war host is defeated, then King Arthur may die.

- The British player can move a second time. The Anglo-Saxons cannot,

- A second round of battles occurs,

- It is the end of the turn, the war host is dissolved, all areas controlled by the British are back to 2 000 men for kingdoms and 500 for cities. The Anglo-Saxons grow in size in their home bases, though if they have been raided recently they may remain at 0.

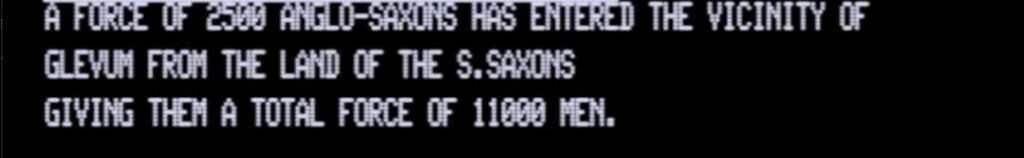

After each battle, Anglo-Saxons armies that are too numerous (the threshold seems to be at 5 000 men) can be hit by a famine / disease, and lose a good chunk of their men, which avoids the creation of unbeatable armies.

It is a whack-a-mole in that the Anglo-Saxons can never be conquered or destroyed, but there is some strategy indeed. The player must balance defending his areas (especially the petty Kingdoms from which his manpower comes), counter-attacking to recover some kingdoms or cities and raiding enemy home bases. That’s not deep strategy, there is no resource management, no economy, etc, but still, the game feels neither random nor brainless.

Rating : Poor

D. Scenario design and balancing

There is only one scenario without even a difficulty slider. By my 4th session, I was able to win consistently, with a perfect result like the one below in all my subsequent games except one.

Rating : Very poor

E. Did I make interesting decisions ?

Yes, every turn. There is a balance between attack and defense – and then what to defend every turn, especially at the beginning of the game (when all the Anglo-Saxons still have teeth) or in your first sessions when you don’t know the game. After a few matches, the game will be way to easy for the decisions to be interesting.

F. Final rating

Obsolete. The game is saved by its original theme and its very short sessions, and I found it better in its simplicity than the earlier Emperor. I still had fun for about one hour, which is pretty good for a 40 years old game, and better than what some modern games offer.

Unfortunately, King Arthur will be the last game by Richard Bodley-Scott covered here for a long time. His two other games (Triumph of Rome and Hannibal) are currently lost. On the other hand, Molimerx has 3 other similar wargames (Napoleon, William the Conqueror and Crusaders) that I will cover eventually. But first, I will finish defending England from the Soviets in North Atlantic ’86.

2 Comments

Very interesting to see Richard Bodley-Scott’s early computer games covered here. It looks like one D. Peckett coded the BBC ports and also wrote the later games you mentioned. Will be nice to see those covered too later.

I’m more familiar with Bodley-Scott work in the 80’s on DBA/DBM/HOTT but I’ve started dipping my toes into FOG II based on your recommendations.

Hopefully you like FOG2. I found the game fresh, it plays like a tabletop wargame without all the hassles.

D.Peckett did not write the other games (the 3 of them are by Simon Ford) but he ported all the BBC versions. The credits for Simon Ford are missing for the ports of the other versions.

I had to search what DBA/DBM and HOTT were. Now I need to find those manuals :).