[Commodore 64, ASP Software]

After years of wargaming, I reckon I played fewer than 10 empire-building games which managed to avoid a boring finale where you push your armies in all directions and win by massive economical superiority. This is particularly frustrating because the Roman Empire had solved this game-design issue some 1500 years ago with this engrossing feature called the Barbarian invasions, and this is the challenge offered by ASP Software’s Fall of Rome.

I played a handful of games based on the Fall of Rome theme in my gaming career, and in my experience, they are rarely good. If the invasions are too strong, it is a frustrating experience as the player’s only agency is in the order in which he loses his territories. But if on the other hand, the invasions are too weak, then the player may very well push the borders to India & Hyberborea by mid-game, and then what you have is another empire-building game. It is hard to make losing fun.

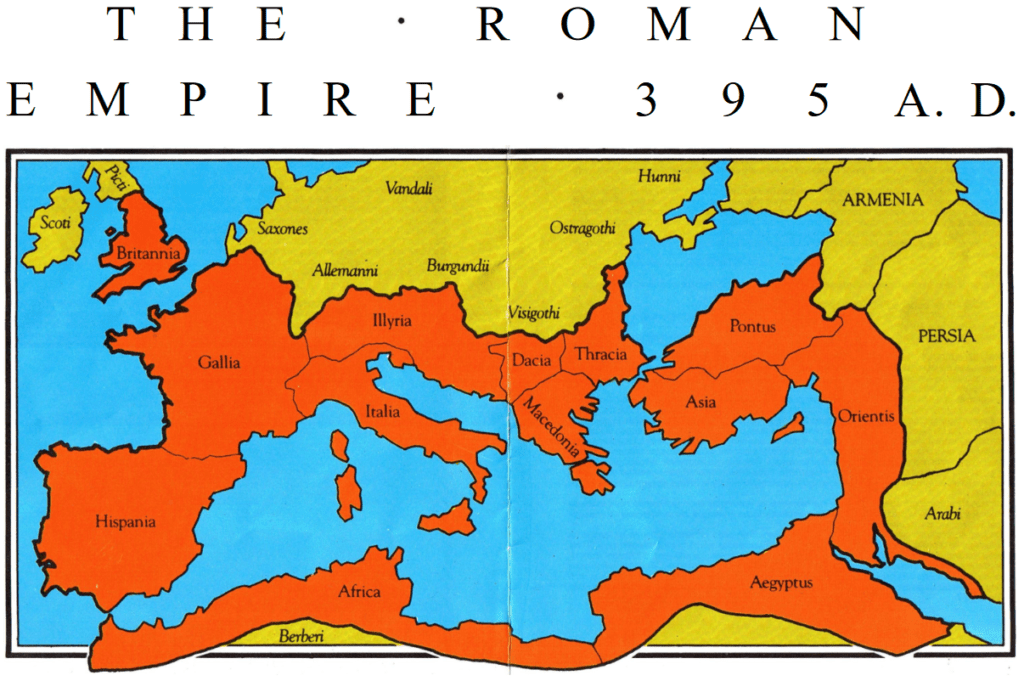

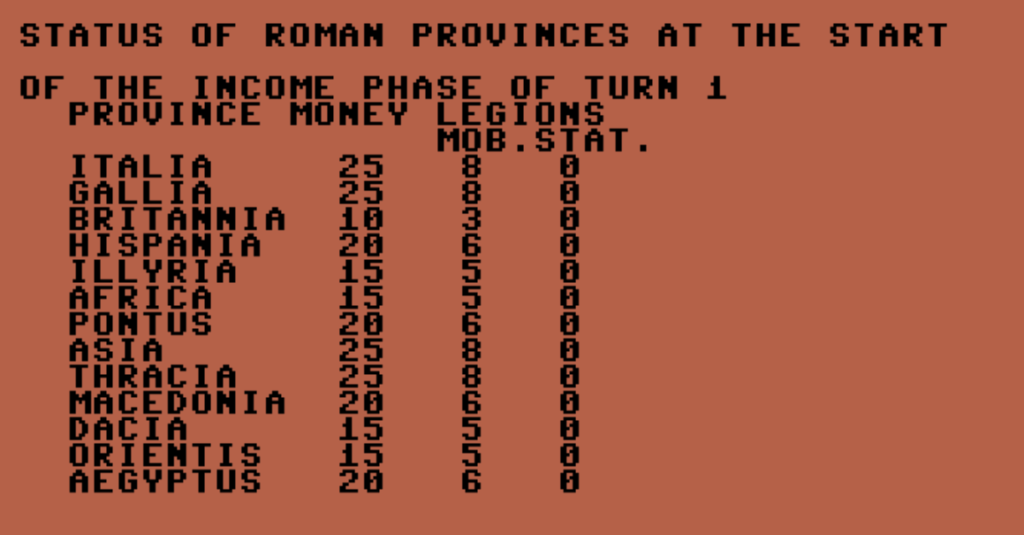

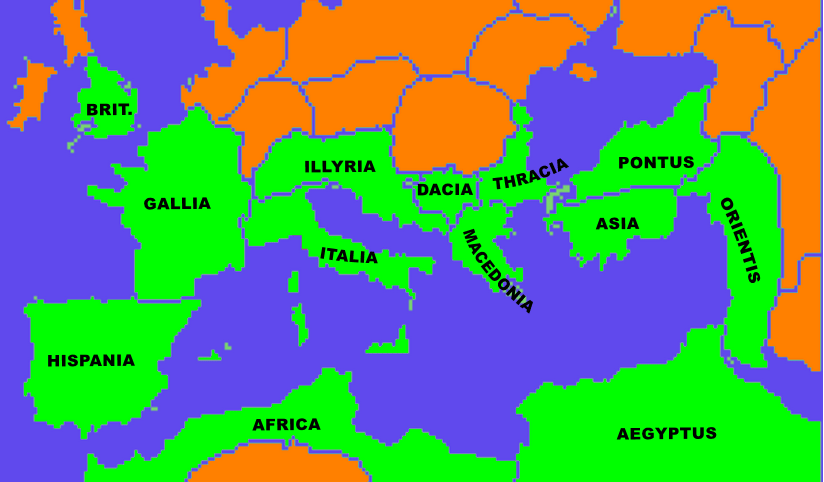

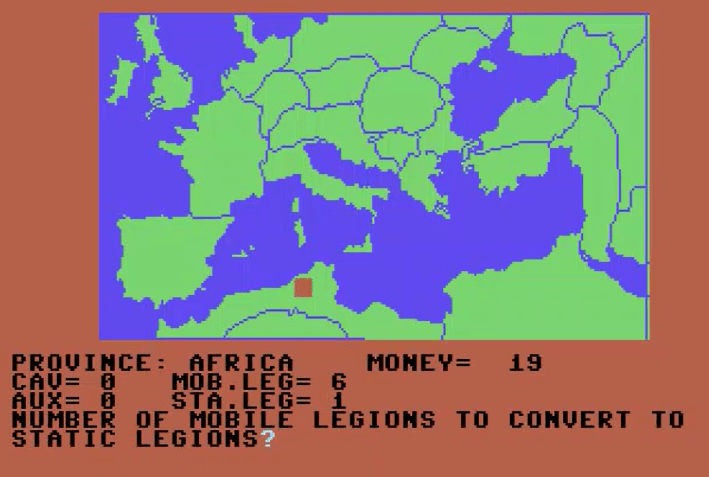

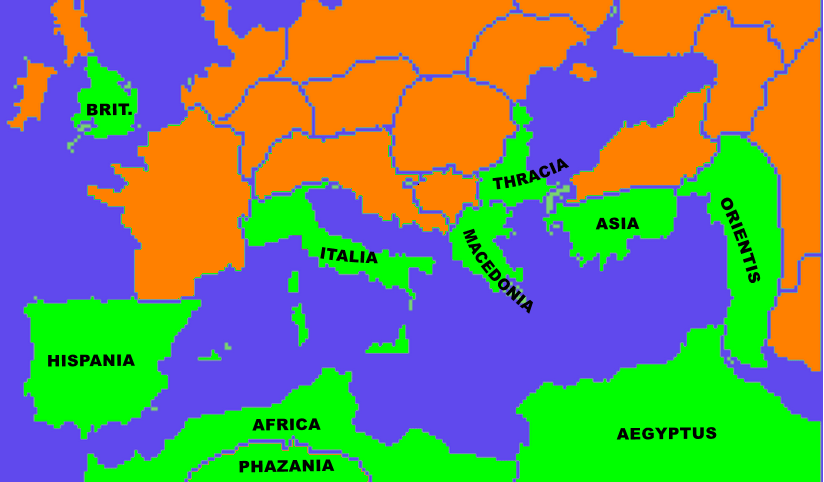

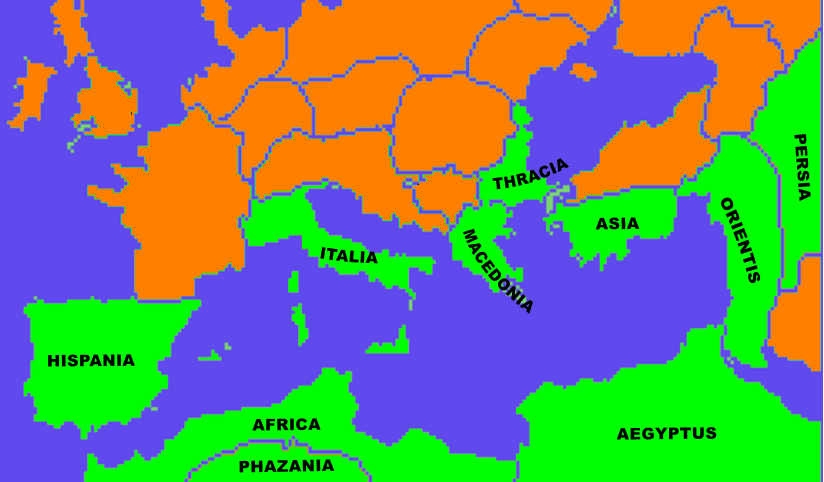

The Fall of Rome starts in 395 AD, when the two halves of the Roman Empire have been reunited for the last time under Emperor Theodosius. The Roman Empire is at its apex, with 13 provinces – including Dacia which in real life had already been abandoned at this point in time.

“Scoti” in Ireland is unintuitive, but correct.

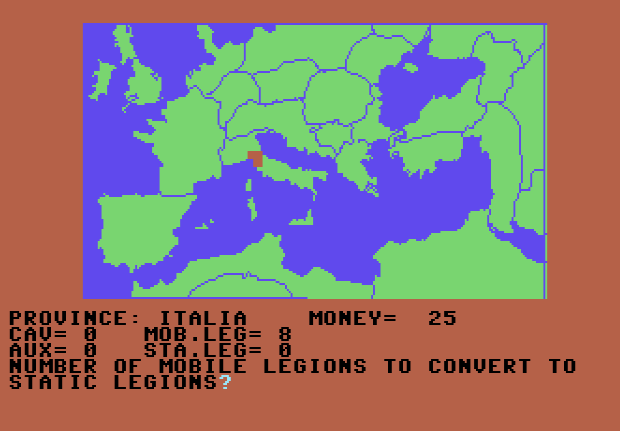

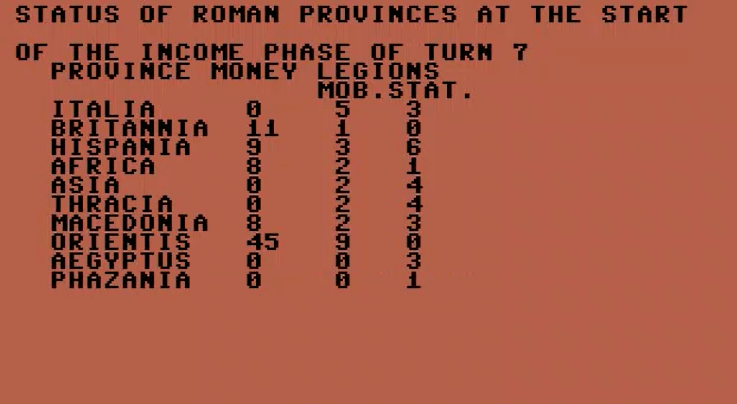

The Rome that I take control of is ready to fight whatever fate throws at it, with each province already fielding as many “mobile regions” as they can economically maintain.

But keeping this army as is would be a mistake. For strategical flexibility, I need to transform some of those legions into “static legions” (moving their maintenance cost from 3 to 1), allowing me to save gold. This gold can then be transferred, along with the remaining mobile legions, to those provinces I really need to defend.

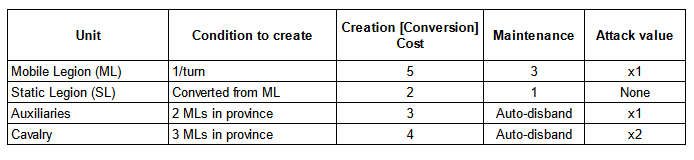

But I cannot ramp down too fast either! I can only build one new mobile legion by province by turn (for a cost of 5 gold). Moreover, static legions cannot be converted back and are also particularly weak: they don’t kill barbarians, they just keep control of provinces as long as they survive. Finally, mobile legions allow the recruitment of the two last possible units: auxiliaries and cavalry, which disband at the end of each turn.

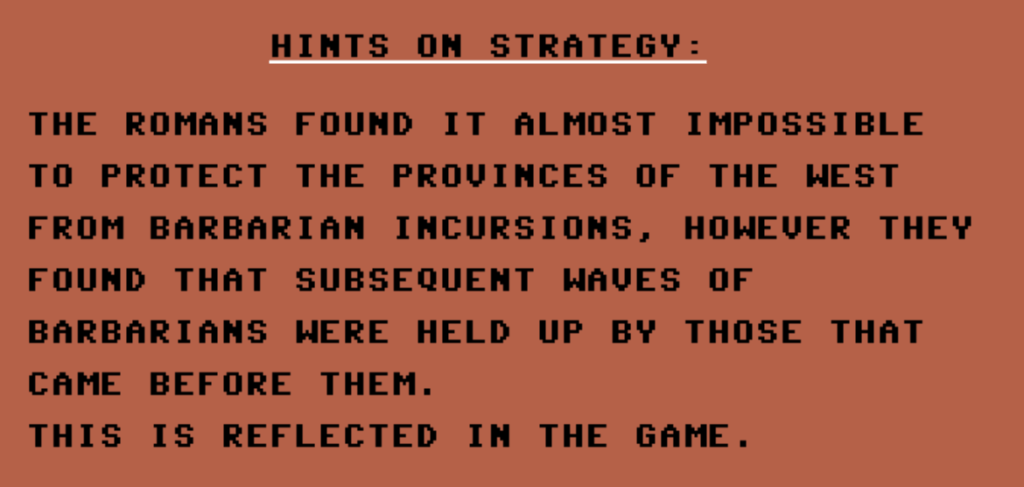

Finally, the game starts with a specific warning:

Year 395

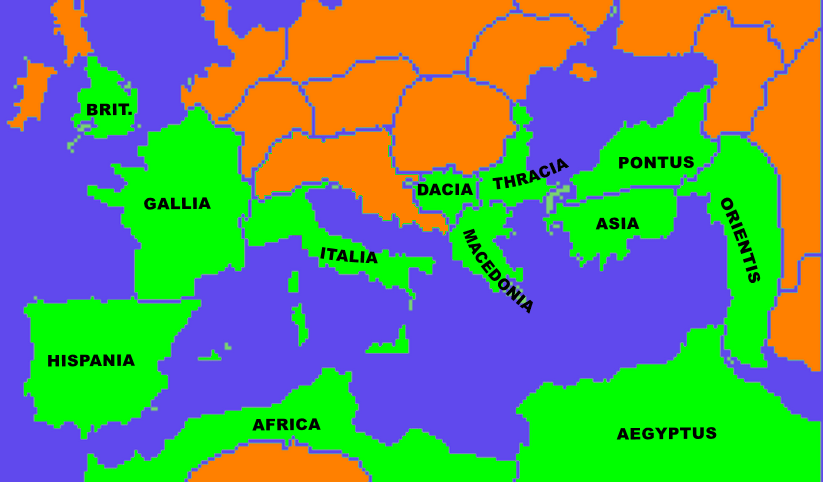

My first decision is to mentally split the world into 4:

- What I can sacrifice: the provinces of Britannia, Illirya and Dacia – none of them rich nor strategically located,

- What I should try to defend: Thracia (isolated, but rich), Pontus (protects Asia) and Macedonia (direct access to Italy)

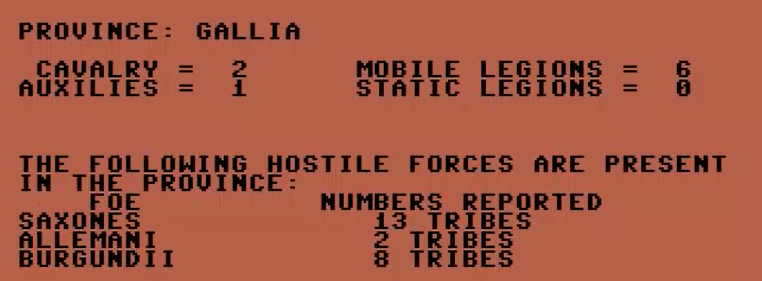

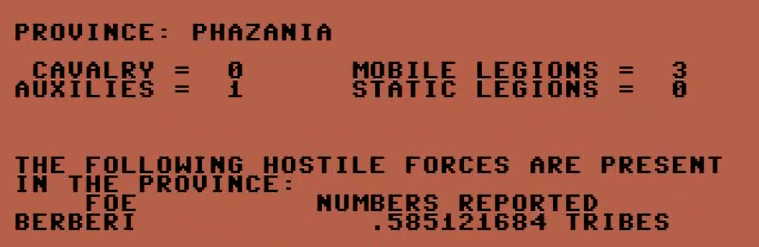

- What I must defend: Africa (potential to become totally safe if the Barbarians in Phazania South of it are quelled), Orientis (strategic location) and Gallia (rich AND strategically situated. Also, my real-life country!)

- The safe provinces: Asia, Aegyptus, Hispania and, well, Italia. No barbarians there at the beginning of the game. If those provinces are threatened, it means something went wrong. I am sure they will, in due time.

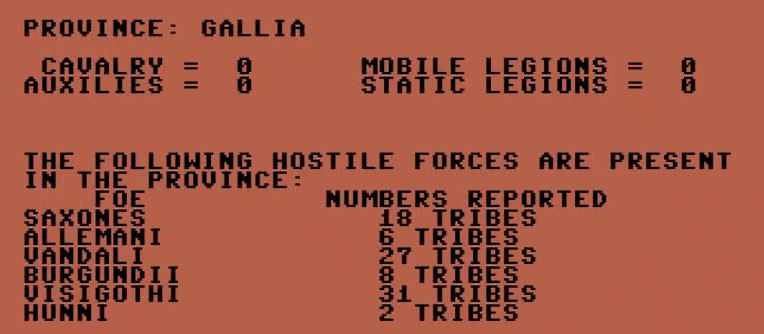

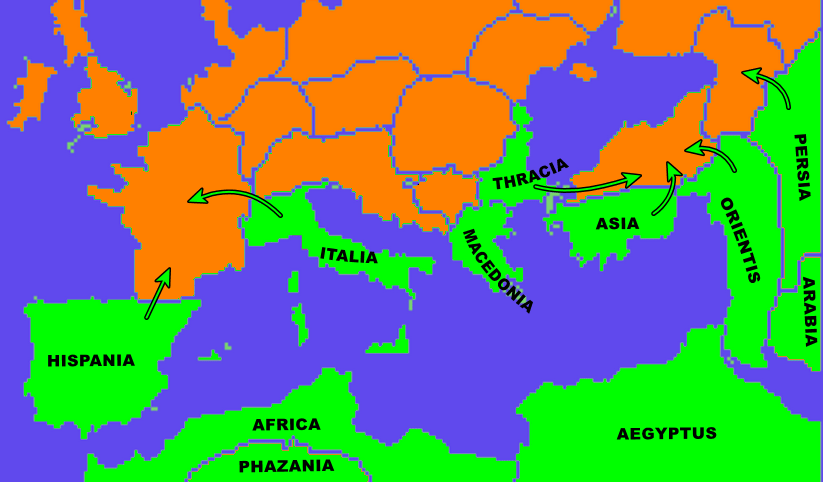

Among the “must-defend”, the one the most at risk initially is Gallia. Happily enough, I can easily funnel troops and money from the safe Italy and Hispania, and if needed from Illirya.

In the East, my posture will be to wait and see. I don’t know the starting allocation and strength of the Barbarians so I feel it is better to keep an army in reserve and see whether I will defend Thracia, Pontus, both or none. Meanwhile, I can go heavy on Orientis.

Well, enough strategizing, it’s time to act! A turn is split into 3 phases.

- The first phase of the turn is the recruitment phase, in which I convert Mobile Legions to Static Legions and recruit new units (Mobile Legions, then Auxiliaries and Cavalry). The game sweeps the regions one after the other:

Whatever money is left in a region can be moved to a neighbouring province (including Africa and Macedonia for Italia), though it will only “arrive” the following turn.

Generally, I don’t convert static legions for provinces directly on the front. Everywhere else, I convert 2-3 static legions, except Spain where I convert no fewer than 6 to make it Gallia’s purveyor of cash.

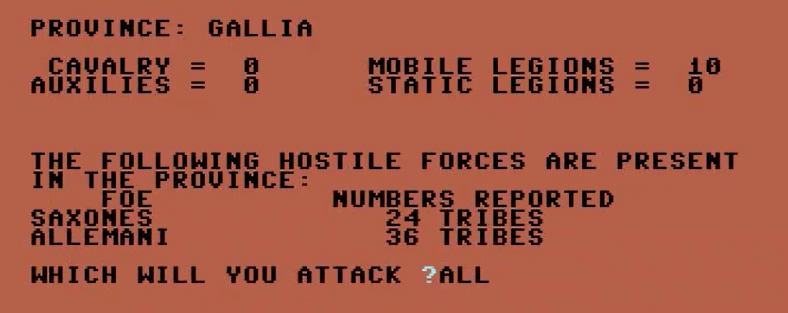

- The second phase of a turn consists of transferring armies between (neighbouring only) provinces. Gallia soars to 11 mobile legions, the rest of the provinces receive a maximum of 1 mobile legion if they are on the front.

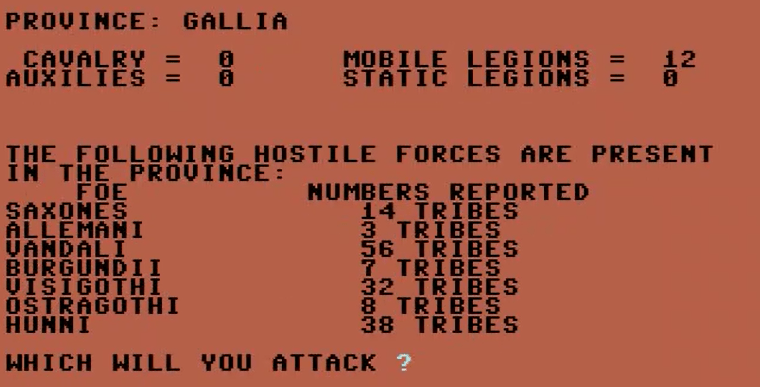

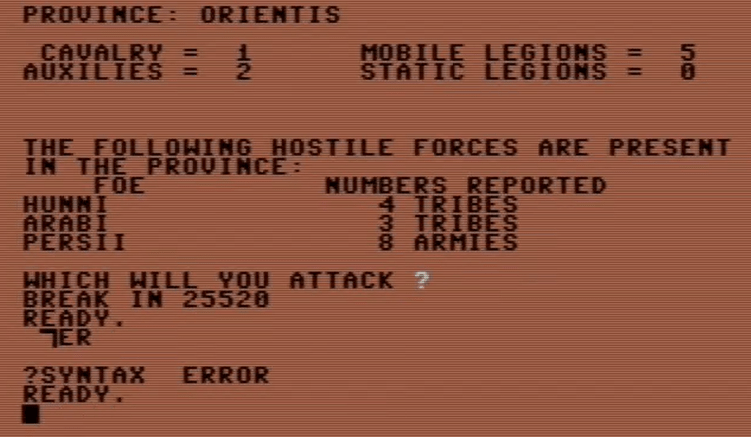

- The final phase of the turn is the resolution of the “combats”. In each province, the player chooses which tribe to attack (if there is only one, it is automatically attacked), and then the surviving barbarians retaliate.

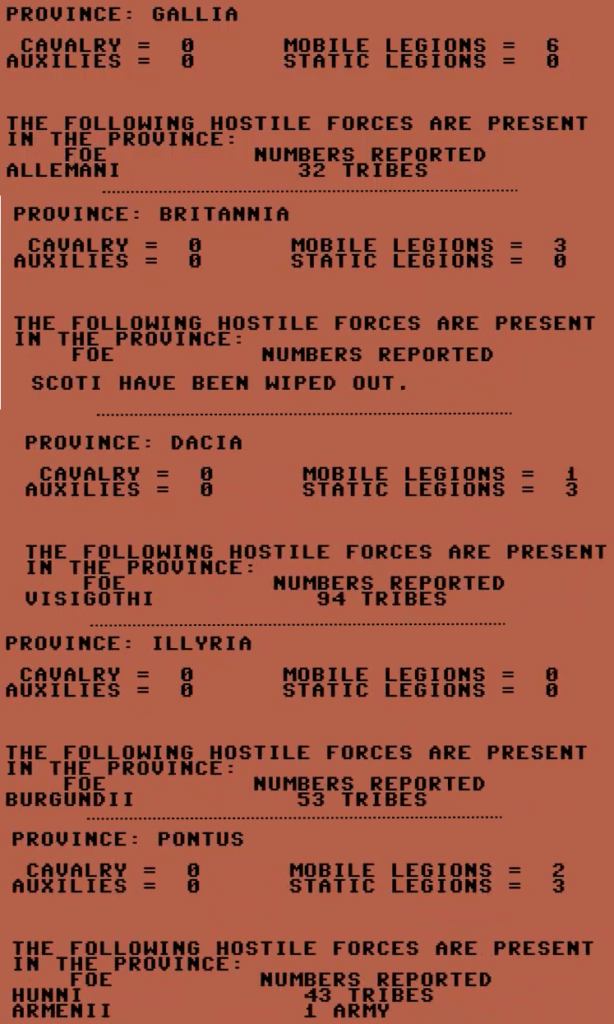

The turn goes reasonably poorly. I lose Illyria against more than 50 Burgund tribes. My hold on Dacia looks shaky too, with 94 Visigoth tribes squatting it – it is a miracle it held this turn. Gallia is another hot spot with 69 Allemani tribes, but after a battle I reduce them to the more manageable number of 32 tribes.

I also keep Pontus under control despite an overwhelming number of Huns, destroy the Scots in Britain, crush a Persian army in Orientis and fend off the Berbers in Africa. It is not looking great, but it could have been worse.

Year 400

I am down to 11 provinces and one difficult decision: what to do with Dacia and Pontus. Dacia looks unsalvageable, and I will abide by my decision not to invest in its defence. On the other hand, I have a good chance of holding Pontus – 40 Hunni tribes is a large number, but manageable given I have no other burning issue in the area.

In the West, I transfer more reinforcements and resources to Gallia, but also spare some for Africa: the sooner I can conquer Phazania in the South, the sooner I will be able to transfer all my forces to the Northern side of the Mediterranean.

Again, the resolution phase goes pretty terribly. Dacia falls as expected, Pontus may be next on the list when the 40 Hunnic tribes become 70 tribes – the only Roman survivors of that onslaught are a few static legions. In Gallia, the Saxons join their friends Allemanis in Gallia, and then watch their friends get murdered by my legions – though I lose 4 of these.

There is some good news: the Berbers are chased from Africa, a new Ostrogoth powerful invasion in Thracia is stalled (47 tribes become 21 tribes), the Arabs are destroyed in Orientis and the Romans keep Britannia Romano-British by eliminating some Picts.

Year 405

So far, I have not lost any region I really care about, but I am worried by the attrition rate of my mobile legions – I lose more than I can replace. Still, I am about to solve this, at least in the medium term. If I can conquer Phazania (South of Africa), then there won’t be any more Barbarians in the South and I will have 2 regions safely generating gold and troops every turn.

Henceforth:

- In the South, I move everything I can from Africa to Phazania, and defend Africa with legions from Aegyptus,

- In the North West, as I am running out of legions to defend Gallia, I recruit auxiliaries and cavalry in Hispania and Italia and move them to Gallia. Not ideal, but that’s the best I can do.

- In the East, I unwisely decide I will try to hold Pontus by moving troops from Macedonia and Asia.

This plan does not go as expected. Burgunds from Illyria cross the border of Gauls, and I fail to make a dent in their number. My forces in Pontus are crushed by 89 Hunnic tribes and I lose the province.

Still, my main objective for the turn was accomplished, and I managed to take a foothold in Phazania!

Year 410

For 410, my plan in the West does not change: feed troops to the Gallic meatgrinder. This time, I will bring my reserve from Italia, which I can now replace by my troops currently in Africa. I hope to pacify Phazania this turn, but for now I know the Arabs will be too busy fighting me in Phazania to migrate.

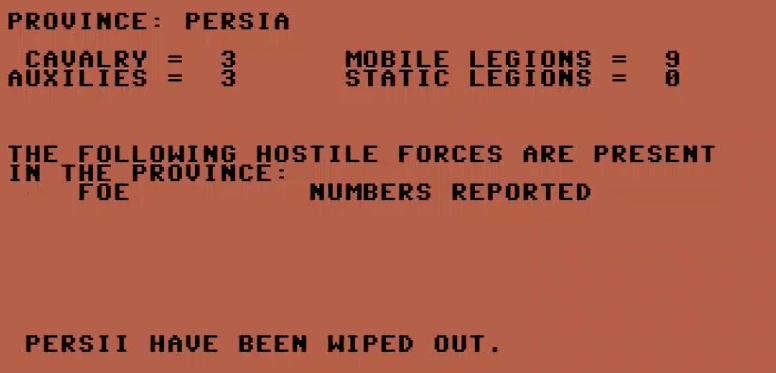

In the East, Thracia is now surrounded. I will fortify as much as I can, but I also want to accumulate some troops in Orientis to strike Persia – the richest province of the game.

For once, the turn resolution goes swimmingly. Losses across the Empire are marginal. I make Orientis barbarian-free again and Gallia reaches an all-time low in terms of Barbarians:

As for Phazania, I almost completely clear it:

I am a bit worried about Thracia (25 Hunnic tribes), but it should survive with reinforcements from Macedonia.

Year 415

Disaster! Barbarians pour into Gallia from all the possible borders, and the province that looked safe the previous turn is overrun!

Britannia is cut from the rest of the Empire, and I must immediately reroute my African reinforcements to the almost defenceless Hispania!

Year 420

While I reorganize my defence in the West and push back a massive force of vandals (30+ tribes) trying to settle in Italy, I carry on accumulating resources in Orientis with cash and armies coming from Asia and Aegyptus:

Not much happens, except my forces in Thracia and Britannia taking losses – which for the latter will not be replaced.

Year 425

Time to make the Roman Empire Great Again, and to make Persia pay for it. In earlier testing of the game, I found out that Persian armies can be absolutely devastating, so I bring overwhelming forces to Persia : 9 legions, 3 cavalry and 3 auxiliaries.

The Persians have 15 armies waiting for me and… they are annihilated without any losses! I am now in control of the wealthiest province in the game, and while it cost me a lot of cash, it did not cost me any of my precious legions.

Elsewhere in Europe:

- I lose Britain but I had already made my peace with that,

- Thracia is now in a critical situation,

- the first barbarians arrive in Hispania, but for now in low numbers so the Spaniards make them understand they can’t stay here muchas-gracias.

Year 430

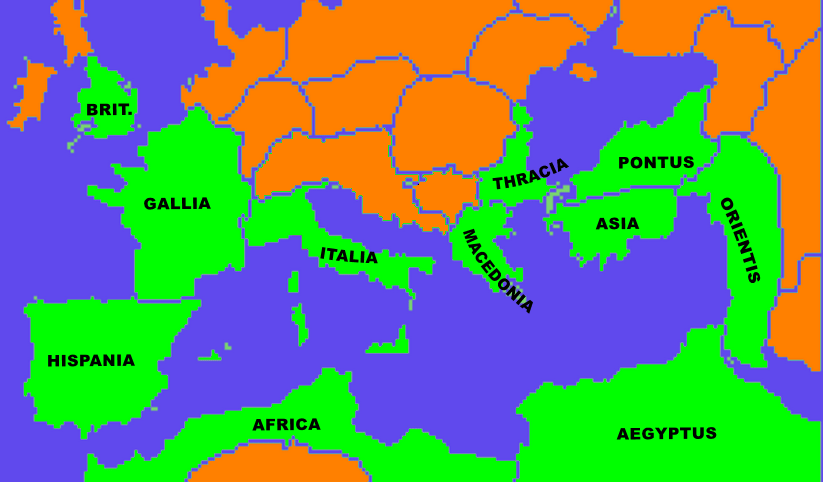

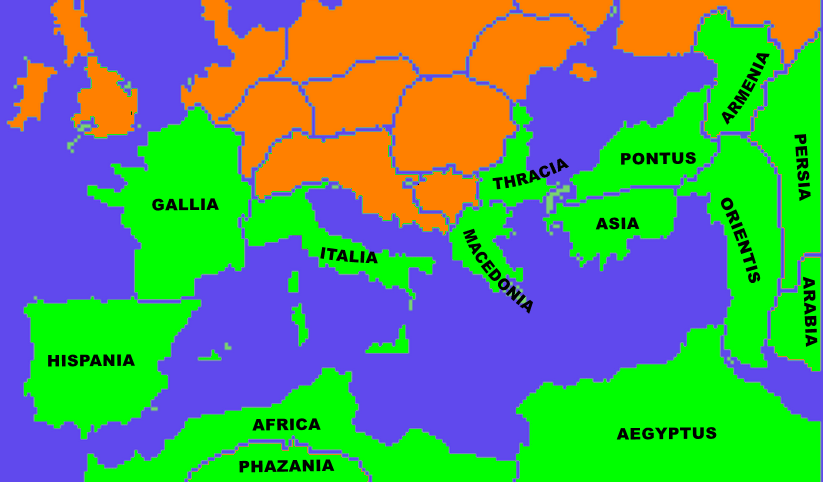

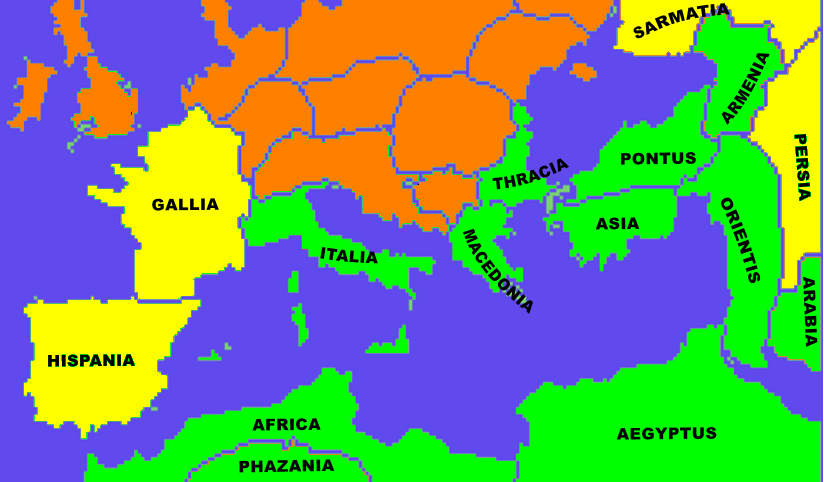

I reached the second half of the game, and the shape of the Roman Empire has changed tremendously.

Overall, I feel I have a stronger defensive position than when the game started. Africa is safe, and when I will seize Arabia the Orient will be safe as well. Hispania and Italia are chock-full of legions and with only 1 or 2 borders shared with the Barbarians I don’t expect the kind of surprise that lost me Gallia. My weak spot is Thracia, and to a lesser extent Macedonia.

My two short-term priorities are:

- Thracia, with massive reinforcements coming from Macedonia, replaced there by reinforcement from Italia, replaced there by reinforcements from Africa,

- Arabia, where I attack only with a limited number of legions because the territory will not be able to feed them at the end of the turn.

It goes above expectations in Thracia: Rome finally has the upper hand against the mass of local Ostrogoths and I destroy more than 40 tribes. On the other hand, I don’t immediately annex Arabia as I did with Persia, and I am going to have to pour in more troops to conquer this region.

Year 435

The Barbarians are fairly quiet this turn, allowing me to finalize the conquest of Arabia and consolidate Thracia and Macedonia.

Year 440

I feel I have passed the “strong defensive position” threshold and now have massive armies in Persia, Orientis but also Italia. Time for a glorious finale.

Meanwhile, the Vandals think the same and cross in huge numbers in Hispania, establishing a strong foothold. Everywhere else, the Barbarians trying funny things come to regret it immediately, given all my border regions are strongly garrisoned.

Year 445

With two turns left, I go all out, leaving only a meagre defence behind me.

In Gallia, I am faced with a melting pot of Germanic tribes, plus some Huns. My 12 legions manage to reduce the number of Vandals a good deal, and more importantly, 3 of my legions survive.

In Pontus, close to 40 tribes of Huns are met with 12 legions, plus cavalry and auxiliaries, coming from 3 directions. The Huns all die and I lose only one legion. Once again, overwhelming forces prevail.

In Armenia, I don’t find any Armenians – they have all been replaced by Huns. These resist my attack, but 6 of my legions fortify.

Rome is back, baby.

Year 450

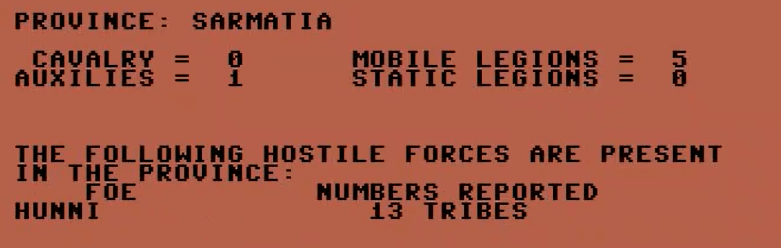

It is the last turn. I consolidate Gallia as much as I can. In the East, my troops in Pontus are transferred to Armenia (no other target), allowing my army in Armenia to move North to Samartia, where I find yet more Huns:

I hold Gallia by a fingertip, and finish the conquest of Armenia.

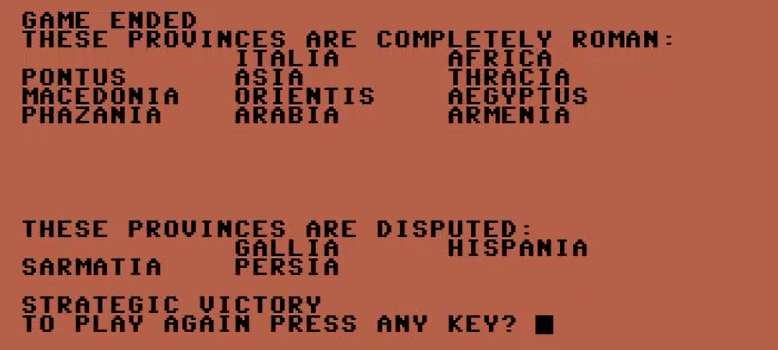

The game ends with a decisive victory, with the Roman Empire much larger than it started.

Let me tell you that this was not an easy feat; I trained on the game a lot and I don’t think the real Romans had a chance to nail it at the first attempt – especially with all the civil wars going on at the same time.

Ratings & Reviews

The Fall of Rome, by Martin Edwardes, published by ASP Software, UK

Genre: Strategy

First release: May 1984, probably a more confidential release late 1983 on Commodore 64

Average duration of a campaign: 1 – 1.5 hour

Total time played: 6 hours

Complexity: Average (2/5)

Final Rating: Two stars

Ranking at the time of review: 12/116

Born in 1953, Martin Edwardes was first exposed to computers at 15 at the Erith College of Technology, which in 1968 already had a computing module to complete the Higher National Diploma in Business Studies. Computers triggered Edwardes’ interest, and he pursued a computer science track at the University of Cardiff. After graduating in 1974, he acquired a TRS-80 in 1979, a bit before the boom of personal computing in UK. By 1983, Edwardes, still working on computers, was languishing in a dead-end project to computerize the student record database of the North East London Polytechnic.

In parallel, Edwardes had been an active tabletop role-player and wargamer. Mixing the two cultures, he had designed for his group of players a wargame called Battle of the Ring, which he had no intention to publish but nonetheless proved quite popular. The game came to the attention of Keith Poulter, the founder and the secretary of World Wide Wargamers (initially “UK Wargamers” but quickly enough the name felt too restrictive). Poulter was in 1977 about to launch The Wargamer, a magazine designed to include a full-fledged wargame in every issue on the model of SPI’s Strategy and Tactics, and he was looking for a wargame that would ensure that the first issue of the new magazine would be a success. He managed to convince Edwardes that Battle of the Ring was that game, and the former became not only the first designer of The Wargamer but also its unpaid “game tester, designer and sub-editor“. Later, Edwardes would also contribute Africa (ported to PC in 2006) and Simon de Montfort, but by 1983 his involvement with the magazine had ended.

Bored in his job, Edwardes combined his coding and design skill around 1983 to program The Fall of Rome on Atari. He submitted it to ASP Software, and the game must have impressed whoever was in charge of submissions, because Edwardes ended up as Game Software Manager at ASP Software. He ended up tasked with publishing his own game, in addition of course to all the other games he had to source to feed both the magazines and the stand-alone catalogue. ASP Software at that time was 10 people, all included, as the games were not done in-house but by freelancers.

There is a bit of a discussion to have on the exact dating of The Fall of Rome. Edwardes remembers that the game was released late 1983 on Commodore 64, and in 1984 for the other platforms. Yet, looking in archive.org, I found no mention of a Commodore 64 game of that name in 1983. Instead, The Fall of Rome was teased in ads starting in March 1984, and then finally announced in April with a release date set for the 1st of May 1984 for Atari, BBC Micro, Commodore 64 and Spectrum. A version for the Dragon 32/64 would be added later.

I surmise there was a limited test run in late 1983, and that the feedback was so positive that ASP Software decided to scale up its ambition for the game and launch a real marketing campaign. My practice so far for dates has been to ignore confidential releases if they were followed by a massively more significant release later, so 1984 it is.

A. Presentation: Poor. Text and a map only, though I give credit for some magnificent artwork, both in-game and in-ads.

B. UI, Clarify of rules and outcomes: Poor. The Fall of Rome is easy to play, but it is also one of those games where I had to take notes because you cannot freely check provinces for their situation with regards to barbarians or even economy. It is also frustrating that you have no explanation on the result of battles, only a before/after screen, with results that seem unfair. The game is also slow, but nothing a modern emulator can’t handle.

C. Systems: Quite good. The game system is designed around making the Romans both powerful and unable to stop the tide, at least at the beginning. Mobile Legions are powerful and a group of them is going to win almost any battle, but they are also slow to build and expensive to maintain, and even the largest army can receive massive losses due to the high randomness of combat. Barbarians usually migrate slowly, but because you can only attack one tribe per turn they may be defeated again and again and still overwhelm you – while still giving you time to fall back and regroup after a defeat.

In an email exchange, Edwardes gave me some details about the migration system: each province has a maximum population. Tribes grow in size every turn, but when this maximum is passed, the excedent overflows a neighbouring province, usually on the West. If the new province is occupied by one or several different tribes, then both the newcomers and the guests receive damage, sometimes reducing the final population of the new province. If, on the other hand, the migrants move to a province already largely controlled by their tribe, then they may create an excedent in the new province which will overflow further. This system creates organic waves of migration, with sometimes very few barbarians crossing, and from time to time massive crossings, though on the other hand I found it a bit too easy to conquer the Barbarians from the East.

The reason why I don’t rate the ruleset “good” is that while the system is really tight, I just wished for a lot less randomness. To a lesser extent, I also expected a bit more given the theme: diplomacy with the Barbarians, management of the generals and, of course, Civil Wars. Hard to blame a 1983 game with constraints on memory size for not having that, but one can dream.

D. Scenario design & balancing: Quite good. First, I should state that I played The Fall of Rome a lot more than I first expected – and than I would have if the game had been more poorly designed. After some training and annotating the starting locations of the barbarians, I started my “final game” for AAR purposes on ZX Spectrum… before realizing that The Fall of Rome normally randomizes the starting location of the barbarians (or possibly the “starting migration”), but my ZX Spectrum did not reseed. Said otherwise, I was optimizing based on prior knowledge that I was not supposed to have. I restarted another “final” game on Commodore 64, but that one ended abruptly on a crash with no save; and maybe it was just as well as I had lost the Orient to the Persians. The game after that was the real final one.

Despite 3 “historical” starts those 3 games were fairly different. In my earlier games, the Huns were just another tribe in the East and not my exclusive rival, and while the Armenians never amounted to much, the Persians played a way more important role (hence why I went overboard in my attack). Similarly, depending on the game, Dacia was threatened or ignored, Gallia lost earlier or later, … Given the limited tools available to Edwardes this is well done.

I also appreciate the significant “chrome” that went into the game: the different names of the tribes (with marginally different stats: the Huns are the strongest and most aggressive, the Picts and the Scotis the least), the fact that the Armenians and Persians have different behaviour than the rest of the Barbarians, … The only thing I regret is the lack of customization options (some ports, for instance the BBC Micro one, have a difficulty slider, but that’s all).

E. Did I make interesting decisions? Yes. The Fall of Rome has a very high decision density and all of them seem to matter.

F. Final rating: Two stars. The Fall of Rome throws you into action from the very first turn – no boring build-up or reconnaissance phase – and you will be in “just one more turn” mode until either the end of the game or a particularly unlucky battle. It is this luck factor, combined with the obscure battle results – that really stops it from ranking even higher. Nonetheless, it is the best European wargame thus far.

Reception

Upon its release, The Fall of Rome received throngs of reviews… but they were rarely positive. The most positive reviews came from Home Computing Weekly, twice: 29th of May 1984 and one week later 4th of June 1984. Both reviews – by different authors – are ecstatic: five stars both times, with the second one concluding: “a gripping game, not one you want to start at night… as you won’t want to leave it”. The fact that Home Computing Weekly was edited by Argus Specialist Products (ASP for short) and that those reviews were published within a month of the official release of the game may or may not be a coincidence. I found another positive review in Game Computing (October 1983), also owned by ASP, but here I feel the review is genuine – if only because just like me the author complains that you need to write down information as you go along.

On the other extreme, we have TV Gamer giving the game one star in January 1985 (“The Fall Of Rome is a game I wouldn’t buy. Stay well clear of this one“). The rest of the ratings are decidedly mediocre, in the 50% – 60% range. Alas, reading the reviews it is hard to understand why. All Crash complains about when it gives the game a 55% rating in September 1984 is that it lacks “immersion” and “atmosphere” and is not a “fully blown strategy war game“, whatever that means. Sinclair User (also September 1984) writes a review that looks positive, except for a bug, and yet concludes by saying that “In itself it is a fine game but its faults (…) make it unlikely to win too many converts.”. Only Personal Computer Games (August 1984) is a bit more specific: “The Fall of Rome does not give you the feeling that you are actually in control. If you had a little more control of how each legion fought then you would have a better game”

The Fall of Rome deserved so much better. Deep down, I reckon the reviewers did not like The Fall of Rome but could not understand why they did not like it – but I believe I do. Most gamers have an aversion against losing: losing cash, losing troops and more than anything losing territory – ask yourself in how many 4X games you have quit a game (or loaded a save) when you lost a large city or a fully developed planet. But in The Fall of Rome, the first half of the game will be a succession of defeats and retreats; if you don’t come prepared and looking for a wargame doing things differently, it is not going to be very fun. As for me, I think that’s what made the game unique.

That’s the end of my coverage for The Fall of Rome, but if you want more, commenter WhatHoSnorkers played it on Twitch. His session went differently from mine <chuckles>, and he has a unique style. Martin Edwardes left ASP Software – and the gaming industry – in 1985, never to return. As for me, I know it will make some of you sad but don’t expect The Lords of Midnight anytime soon as I am only slowly grinding through it – but don’t worry there are always more games.