[ZX Spectrum, CCS]

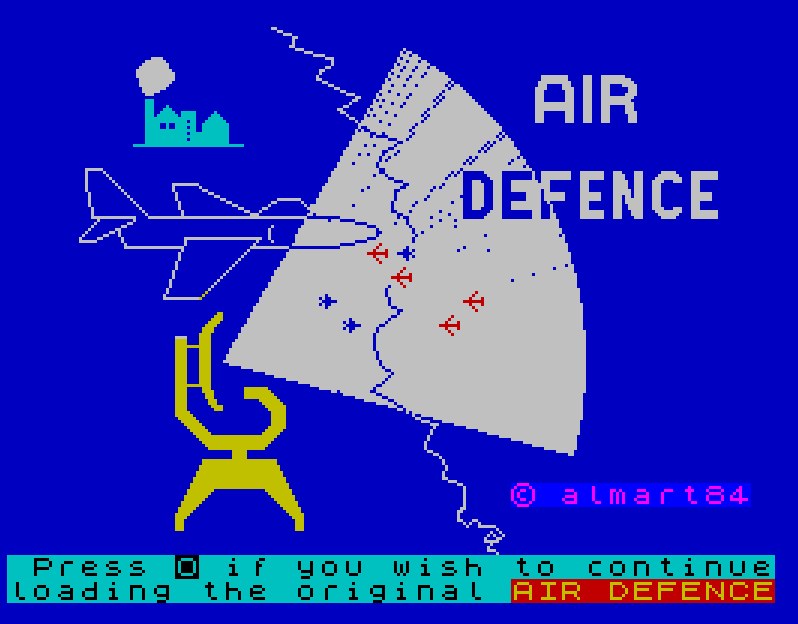

Ah! Another CCS game to fill the gap. The cover looks nice – it could be a banger. Ah! It’s launching…

… wait! I have already seen that somewhere.

NOOOOOOO!

Air Defense is another variation around a fairly sterile concept that nonetheless keeps being iterated upon: allocating fighter wings to enemy attack wings in order to minimize the number of bombs dropped by the enemy bomber. The first game of this family was Battle of Britain (1982), which was then cloned by Pearl Harbour (1984) and then the third time (thus far) as a farce: Panzer Attack (1985)

Air Defence returns to United Kingdom, except that instead of defending England with piston-engines in 1940, I am defending England with jets in the 80s. As for the enemy, the game does not specify it anywhere. Given the art appears to show a British Tornado (on top) dogfighting a British Phantom and that the enemies come from the East, a hypothesis I can’t discard is that I am fighting the rebellious British garrison in West Germany, turned Republican after intermingling with the French. Still, it is more likely that I am fighting the Soviets, so that’s what I will call the enemies.

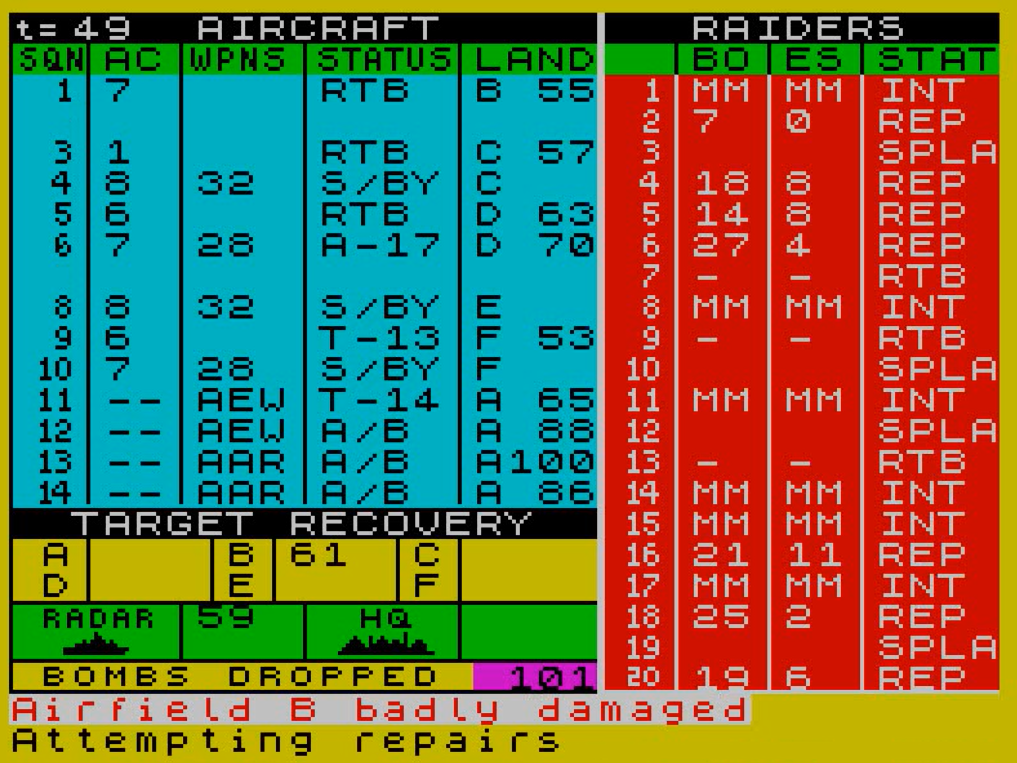

Because it is the 80s, Air Defence adds several features to the formula, including a few assets to play with. In addition to the standard interceptors, the player can rely upon:

- 2 AAR (air-to-air refuelling) planes,

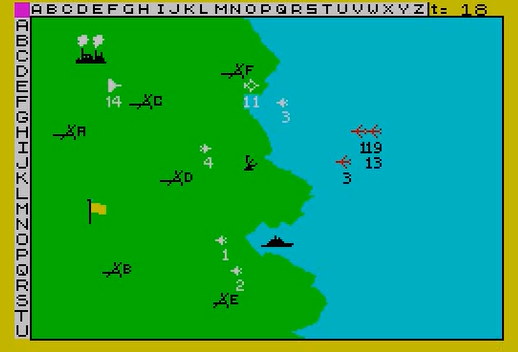

- 2 AEW (Airborne Early Warning) planes to extend the radar coverage as the manual states the top and bottom of the map are not properly covered by the land radar in the middle of the map,

- A static fleet, which has its own radar and shoots missiles at enemy hostiles in the vicinity.

In practice, the AEWs and AARs are never engaged by the enemy, so once they are in position you can forget about them, except to refuel one with the other. Also note that the fleet brings the only surface-to-air missiles of the game, so no Bloodhounds in this game. As for the enemies, they’re dumb-bombing like it’s the Blitz all over again, so they need to physically reach their targets.

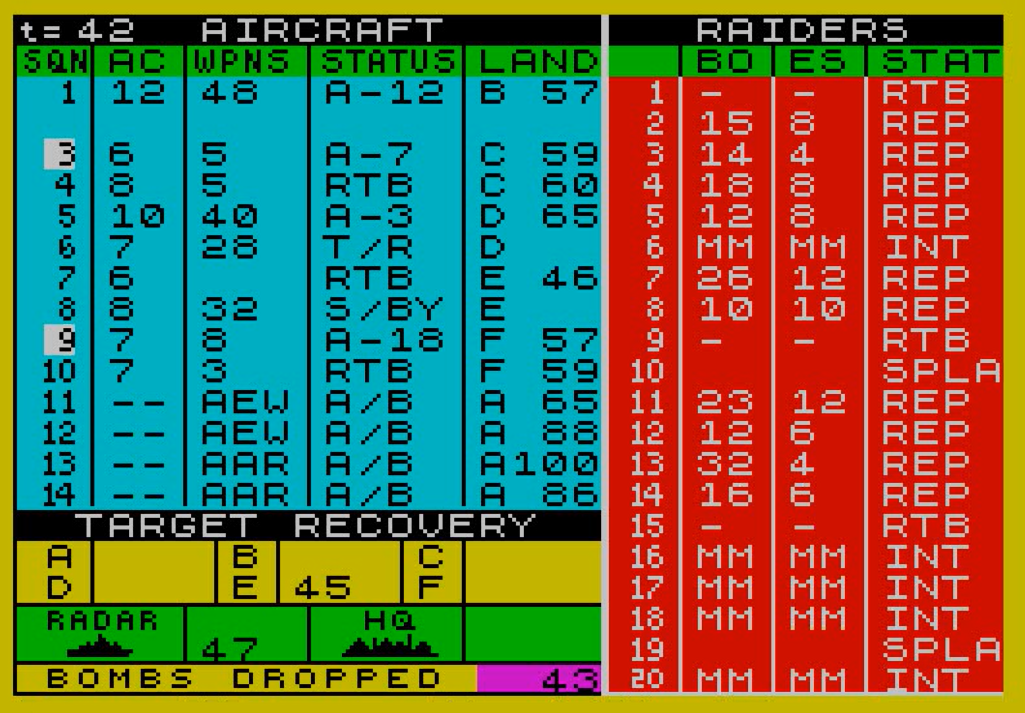

Each plane carries up to 4 “weapons” (I assume missiles), a squadron has 12 planes so each of my 10 squadrons start with 48 weapons. In the example below, I intercept enemy wing #20 after using afterburner (called “reheat” in the game because British English; it gives a bonus of speed at a cost of massive increase in fuel usage). After losing 4 of my planes in combat, I have 18 missiles left, but given how few enemies are detected I reckon I can send my planes back to their base.

I soon regret it, because my radars start to beep a lot and four Soviet air wings are detected.

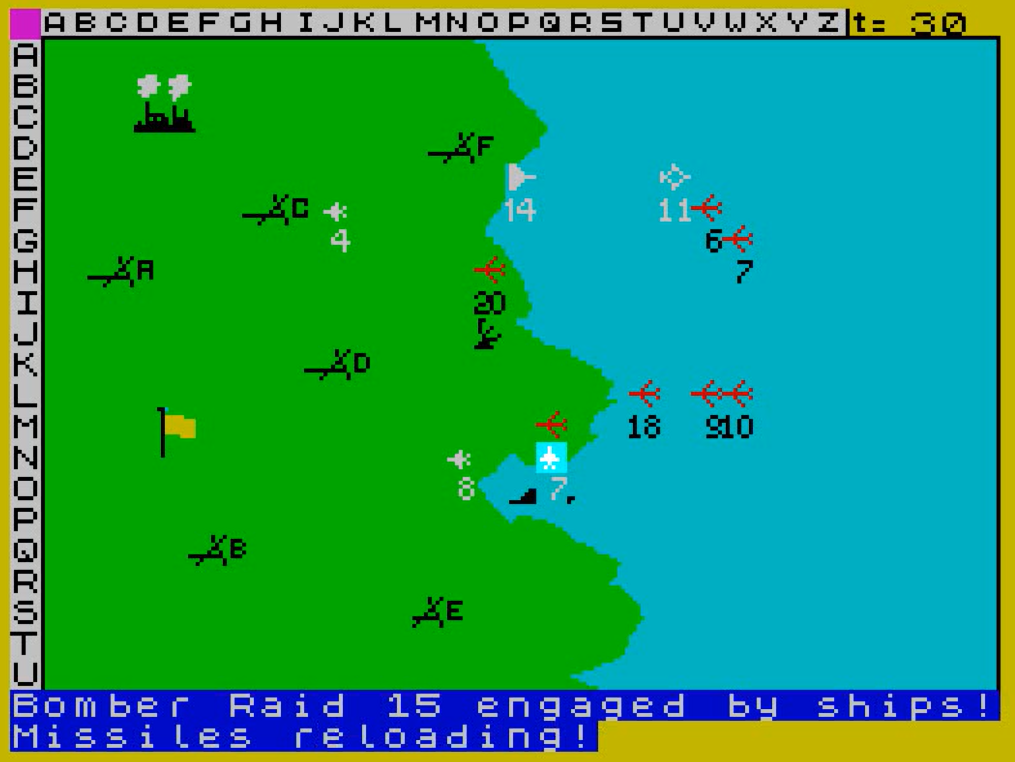

I scramble the two squadrons I have on airfield F and some more from airfields C and D, and a series of air battles ensues.

For a moment, I feel I am in control, but the number of Soviet squadrons does not abate. In similar games, the German/Japanese have 10 squadrons. Here, they have “up to 29”, and I still have only 10 fighting squadrons. There is some help from the fleet which shoots down a few planes with its missiles; however its contribution remains marginal and it is soon damaged by an enemy attack.

In theory, in this sub-genre, the player is supposed to prioritize the enemy squadrons by choosing those with the most bombers [BO] and avoiding those with too many escorts [ES]. The problem is that unlike other games of the genre, this information is only communicated in a secondary menu, and checking this menu does not pause the game.

This means that to play the game properly, I am supposed to:

- open this menu,

- commit to memory which enemy squadrons are high priority and which of my squadrons are still able to fight,

- return to the map,

- find the various squadrons on the map (not always possible as squadrons can overlap one another)

- order the planes around.

This would be very doable if the game was not incredibly slow to play, so by the time I return to the map my 30 seconds short-term memory has elapsed – which squadrons was I supposed to intercept again?

To sum up quickly what happens next, I am overwhelmed by the number of Soviet planes that I don’t prioritize properly, and soon there are enemy air squadrons everywhere. That’s the point where I should say that Air Defence has another feature that comparable games do not have: your ground and naval assets can be disabled. For instance, here I still have my radar…

… and a few minutes later (aka: 2 impulses), my prioritization problem simplifies massively as my radar station is disabled.

My airfields are hit next, making them unable to operate. Planes based on that airfield are stranded in the air, though I can still refuel them until the airfield is repaired.

A bit later, airfields C and D share the same fate.

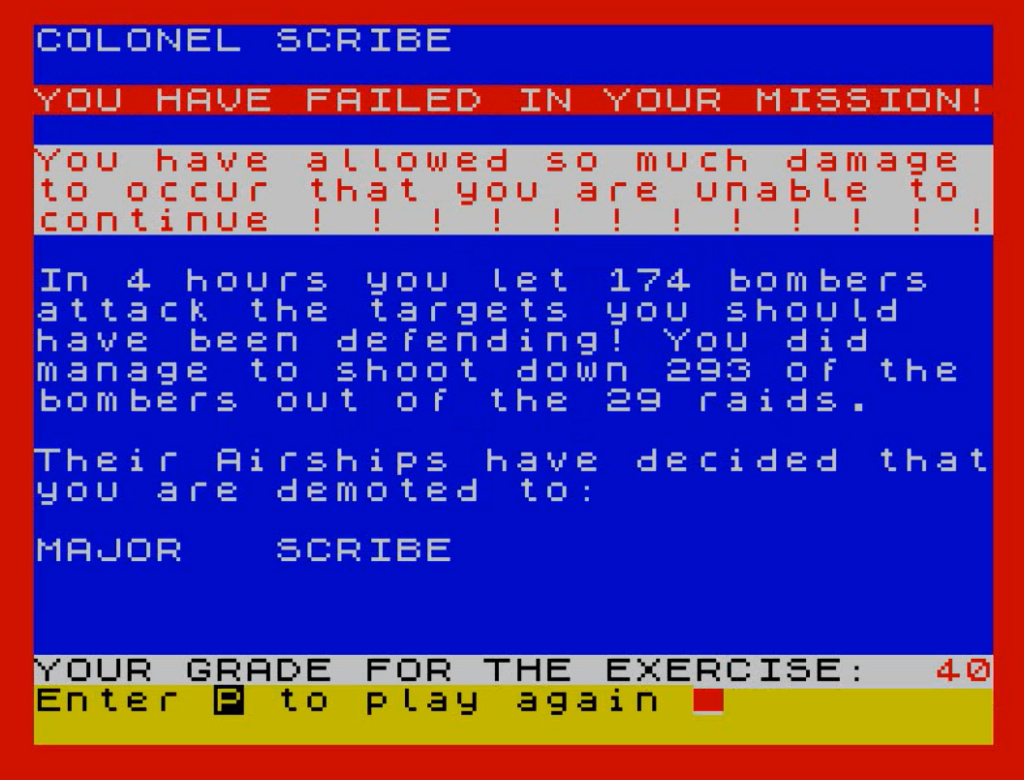

I am now air-defenceless and a few bombs later I lose the game; I passed the unspecified threshold of bombs after which the game is lost.

Ratings & Review

Air Defence by Almart, published by CCS (UK)

First release: November 1984 on ZX Spectrum

Genre: Air Operations

Average duration of a campaign : Around 45 minutes

Total time played : 1 hour

Complexity: Low (1/5)

Final Rating: Totally obsolete

Context – This is another game by CCS, the premier British purveyor of mediocre wargames. The game is credited to “Almart”, who has no other game under this pseudonym. I like to think that it is Robert Erskine, the author of Battle of Britain and Pearl Harbour, who managed this way to sell his game a third time, but I suppose we’ll never know. Air Defence was released exclusively on ZX Spectrum.

Traits – Despite a few innovations, Air Defence is effectively a clone of Battle of Britain / Pearl Harbour. While it has a few features that should create more interesting situations (do I sacrifice the ship or the radar? How do I update my tactics now that I lost that airfield?), it is however a worse game. This is exclusively due to the combination of UX issues and sluggishness. All games of this genre are slow, but they always let you give your orders at any time; Air Defence on the other hand alternates an incredibly long calculation time (around 30 seconds at historical Spectrum speed) between two impulses during which you cannot do anything, and a limited time frame during which you are allowed to give your orders; a time frame that becomes too short if you dare accelerate the emulator. Add to this issue the fact that critical information is found in a side menu that hides the map but does not pause the game (and of course you can’t move from one menu to another during the 30 seconds of life contemplation), and you end up with a frustrating experience from start to finish.

Did I make interesting decisions? I could have, but it was too much patience & effort.

Final rating: Totally obsolete.

Ranking at the time of review: 156/169, which makes it the worst game of the subgenre, though for speed reasons rather than pure design. As commenter Dan quipped in my Panzer Attack review: “It’s moderately astonishing that such a mediocre [Battle of Britain] inspired so many clones…“

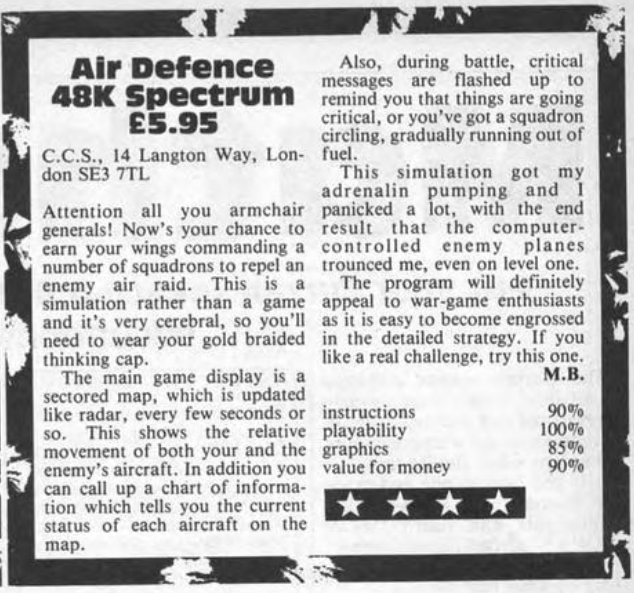

Reception

Unlike War Zone, Air Defence gathered few reviews: Mike Singleton hated it and did not finish his session (“the player would really do much better if he were a computer himself – he would probably enjoy it more too!” Computer and Video Games, April 1985), Angus Ryall loved it (“This is a subtle game, and excellent as an exercise in tactics“, Crash, April 1985), but his review is nothing compared to how Home Computing Weekly described the game in November 1984:

I hope you like these Spectrum games, because with 2-3 exceptions that’s all I have left on my list for 1984, most of them “found” while preparing my 1985 list.