[Julian Gollop, BBC Micro]

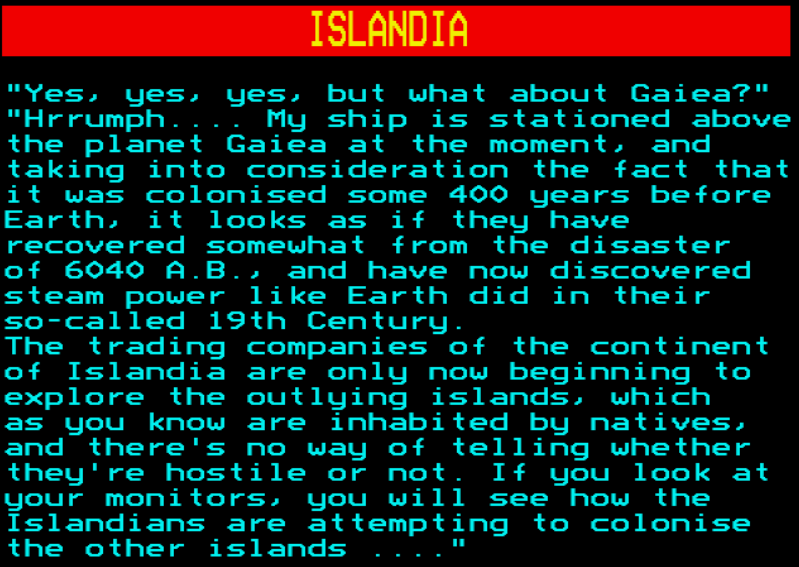

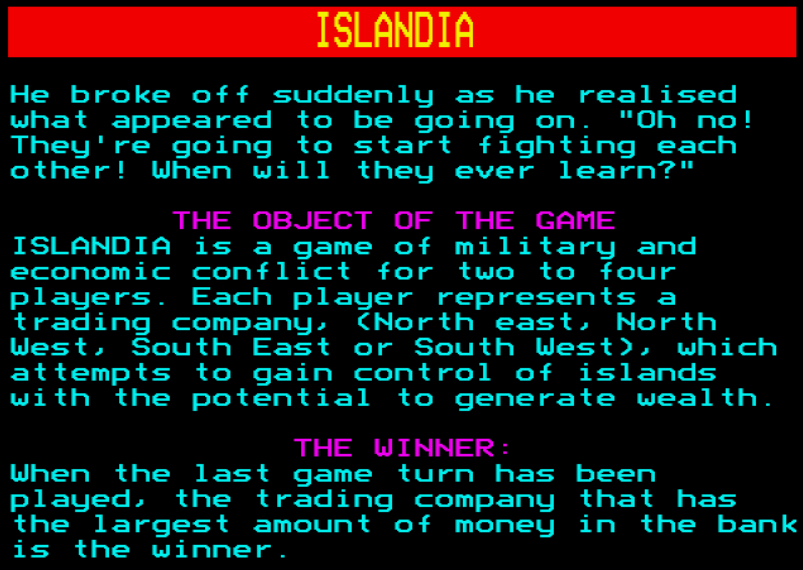

I have previously discussed Julian Gollop and Andrew Greene’s first game, the peculiar Time Lords, which was as distinctive as it was unbalanced and not overly enjoyable. After Time Lords, Gollop independently coded a game called Nebula before collaborating with Greene once more to develop today’s game: Islandia, released by Red Shift in late 1984. Islandia‘s theme and gameplay is more familiar to us than the ones of Time Lords : players are trading companies which must amass wealth by colonizing islands. Naturally, the islands are initially inhabited by natives, but we know History rarely ends with a happy ending for anyone referred to as “natives.”

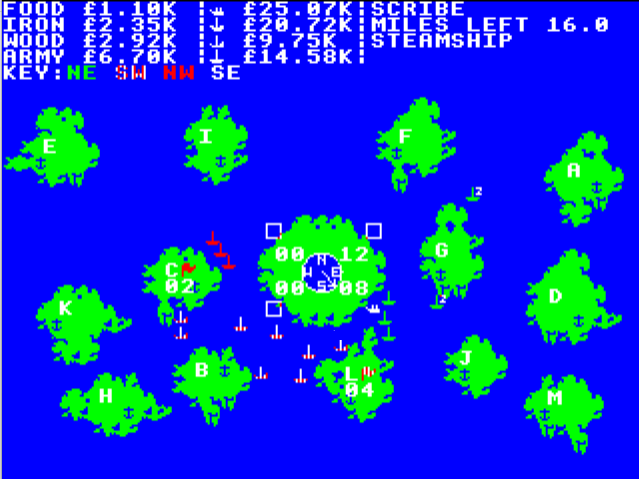

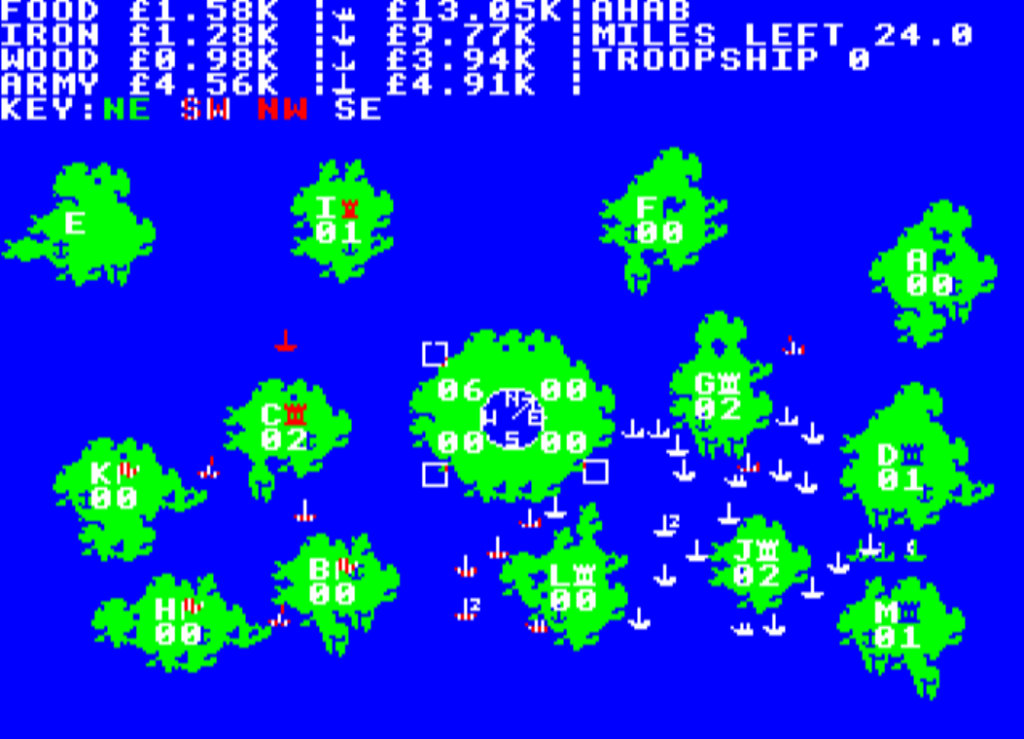

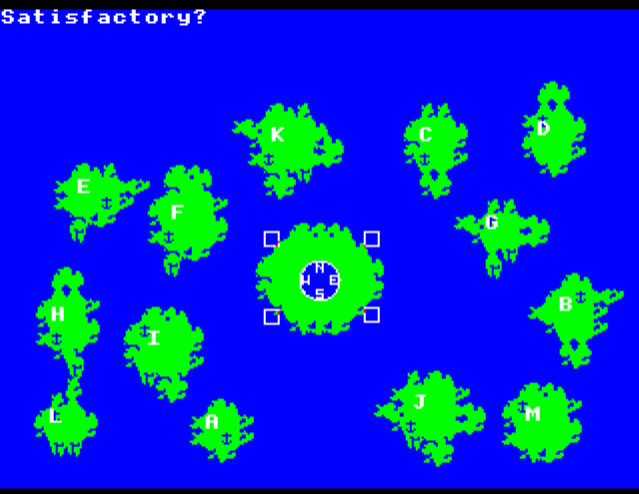

Like many of Gollop’s early games, Islandia is exclusively multiplayer, so I once again assembled a group of volunteers eager to participate in a play-by-email session of an almost 40-year-old game. Together, we agreed on a duration (11 turns), a randomly generated map, and randomized the starting locations and turn order.

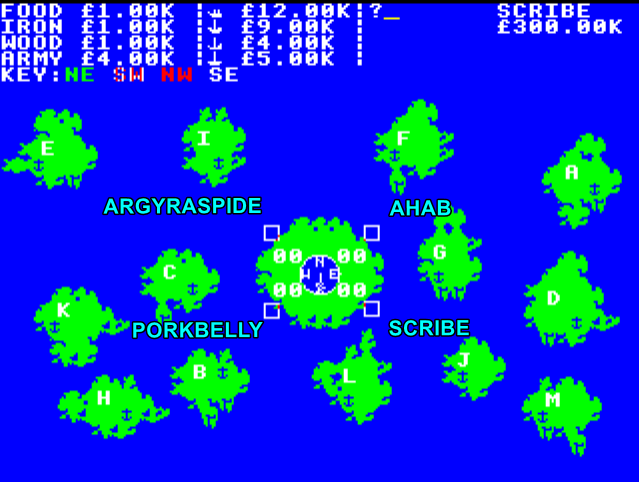

The four players are :

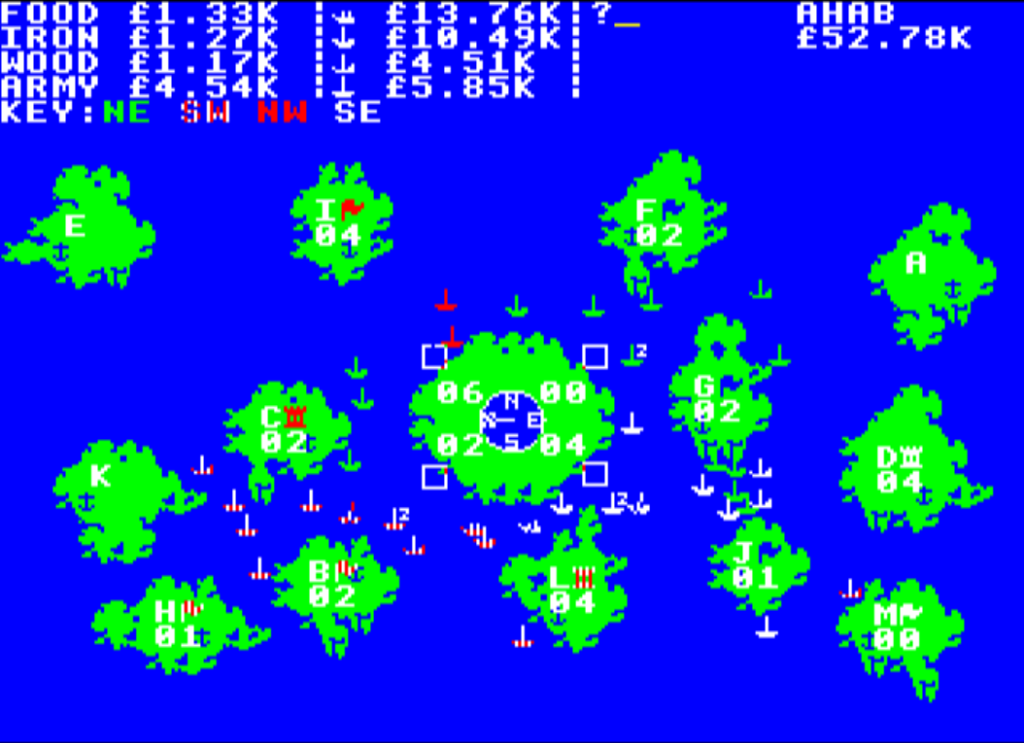

- Fellow blogger Ahab (the Data Driven Gamer), starting in the North-Eastern port and playing first,

- Veteran commenter Porkbelly, starting in the South-Western port and playing second,

- Veteran commenter Argyraspide, starting in the North-Western port and playing third,

- Finally, I am starting in the South-Eastern port and playing last,

Turns are somewhat atypical in Islandia. They are divided between :

- one “economy” phase during which the different players receive their revenue and buy units,

- two movement phases during which they move their ships and attack other players or islands,

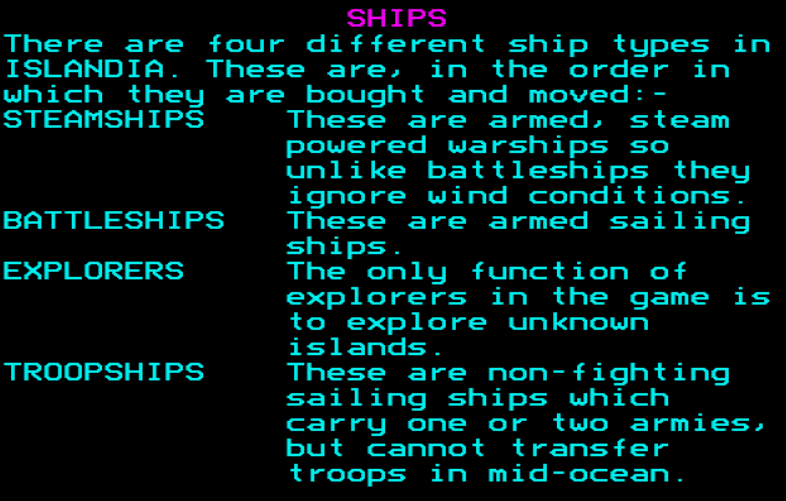

I must first decide what units to buy with the starting £300K. In addition to armies and forts, there are 4 classes of ships to choose from :

Deciding what to purchase during the initial turn is tricky. One unique feature of Islandia is the fluctuation in prices of ships and armies between when you order them and when you pay for and receive them, with the actual cost depending on the demand for those units. If too many ships are bought in the same turn (typically the first turn), their prices will skyrocket. If you overcommit and lack the necessary funds to pay for your order, you will still receive the ships, but you’ll accumulate debt and be charged interest every turn. This is far from ideal, given that the game’s objective is to become the wealthiest player by the end of the last turn.

Naturally, postponing the first purchase also poses risks, as you might not be the only player doing so, and now you launch your first ships a turn late for the same price as everyone else.

After much internal deliberation, I surmise that Ahab and Porkbelly are likely to defer purchasing, so I ambitiously order 5 combat ships, 5 non-combat ships, and 8 armies.

Alas, this turns out to be a blunder, and not for the reasons I had anticipated !

First, Ahab and Porkbelly defy my expectations and also make substantial purchases. Porkbelly acquires 8 ships and several armies, and Ahab 5 ships but 20 armies, bringing the prices turn 2 to twice what it was turn 1. I am still able to pay for my ships, but that expense does not give me any advantage, because of another of Ahab’s decisions :

Ahab, moving first, initiates an aggressive yet highly effective maneuver by positioning his ships as a barrier to prevent me from deploying eastward. He employs transport ships, but they effectively serve their purpose : it requires a minimum of two attacks to sink a vessel, and there is only enough space to attack with two ships. Since one of those two “locations” originates from my spawning point and ships end their movement after attacking, Ahab forces me to either deploy westward (towards Porkbelly) or to obstruct my own spawn point.

Meanwhile, Porkbelly had been communicating with me before I even received my first turn. He told me he left a route open so I can deploy, and that he has taken island L from Ahab, who apparently took it in his first turn.

With a de facto non-aggression pact with Porkbelly, I dispatch two steamships westward. I don’t need to deploy my transports just yet : while I could certainly conquer island L, that would prompt Porkbelly to obstruct my western exit and effectively exclude me from the game. With nothing to do with my non-combat ships, I try to breach the blockade with my warships, but to no avail. One of my two attacks fails. I don’t do any better the following phase, and for all I know Ahab may bring more ships next turn to keep me confined.

I resign myself to negotiating with Ahab. I manage to persuade him that Argyraspide has a non-aggression pact with Porkbelly, and that under the current circumstances my only option is to maintain one as well while focusing on breaking the blockade. My two steamships nonchalantly circumnavigating island L lend credibility to my threat, even though it will take them at least two more turns to arrive. With no enemy on his borders, Porkbelly is poised to win – that’s what I claim anyway.

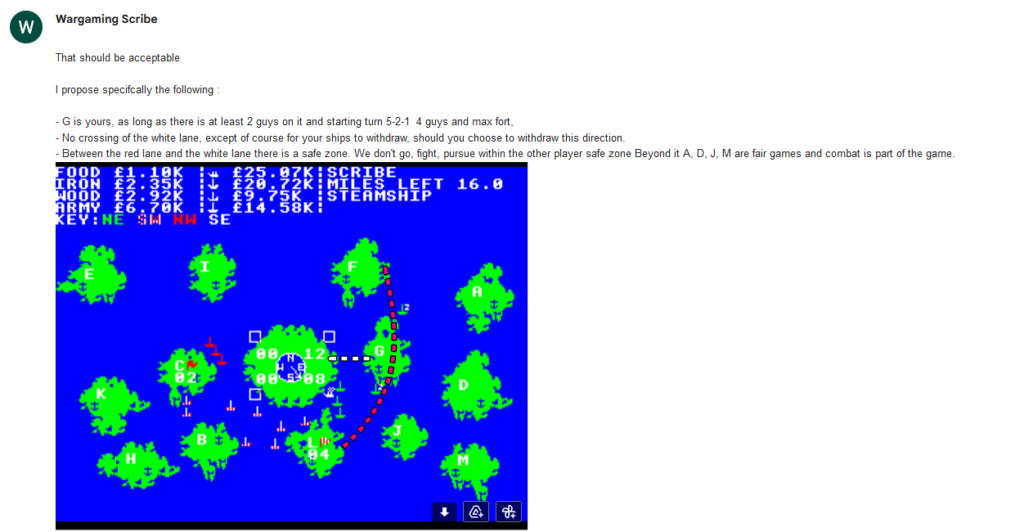

Eventually, we reach an agreement, creating “exclusive zones” where the other player cannot go. Island G is handed to him forever, provided he garrisons it.

Ahab does exactly what was agreed, and he vacates my waters the following turn. Three of his five warships are also deploying toward Argyraspide in the North-West, so I am safe for the time being.

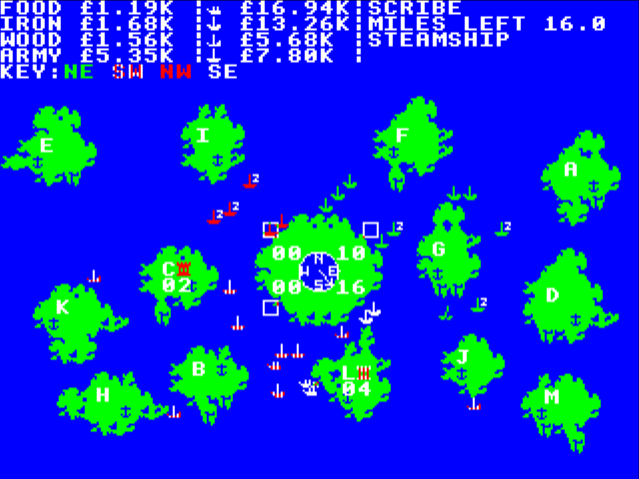

Two things happen during turn 3 :

- Porkbelly immediately realizes Ahab and I have an agreement, and he attacks my steamships. In fairness, I was repositioning somewhere where they could keep the Western passage open,

- I expand East and reach island D in only two movement phases – much faster than Ahab had anticipated – and island D turns out to be the wealthiest island in the game !

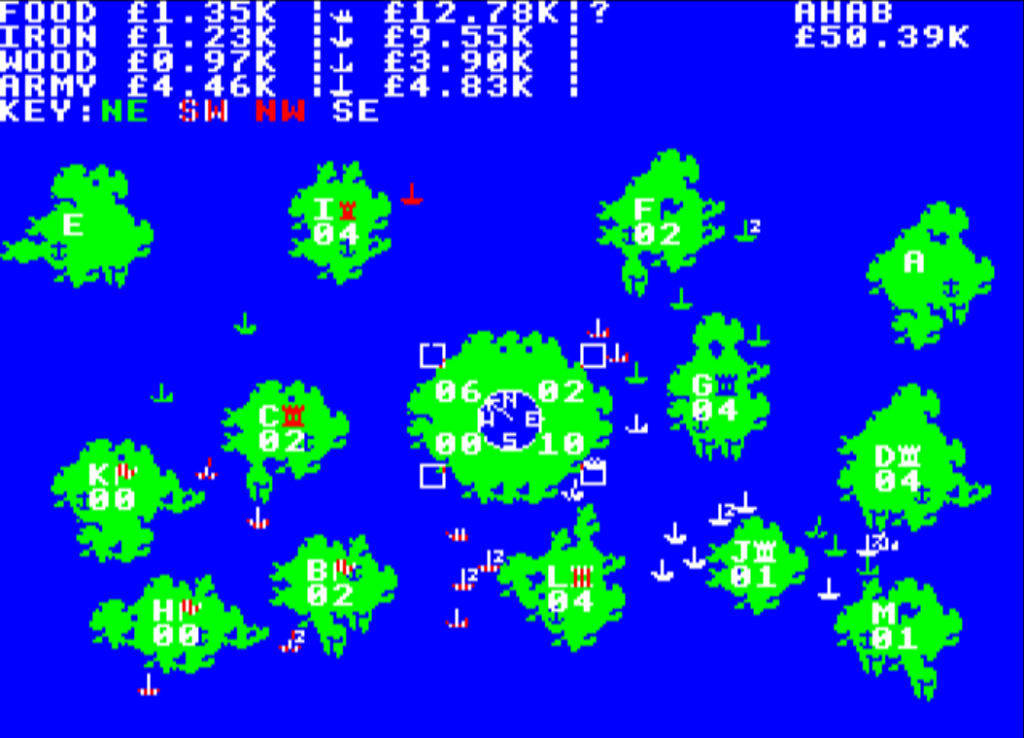

Ahab responds by attempting to obstruct the passage between islands G and J, but I have fortified island D and isolated or not it is hard to attack and generates revenue . Simultaneously, Argyraspide reports a bug: he is unable to construct additional ships. Ahab ignores him and enters Porkbelly’s waters from the north.

Ahab’s offensive allows me to negotiate with Porkbelly the safe return of one of my steamships, crippled but still afloat. I repair it at half the construction cost and then use it – along with the other warships I have in the area – to break the lane of ships Ahab deployed between islands G and J. It takes some time and effort, but I eventually manage to mostly clear the southeast quadrant during turns 4 and 5. In the meantime, Porkbelly successfully repels Ahab’s ships, while Argyraspide remains unable to deploy anything except armies and has to work with one remaining transport ship.

By this point, all of us begin to doubt the fairness of combat resolution. Ahab was repelled by the natives from island A twice, despite bringing an overwhelming force. We start to question whether the game even considers force ratios in combat. As Porkbelly has just reinforced island L with six additional armies, I see an opportunity to try something odd. If I land two armies to island L, I will be fighting (accounting for the effect of fortification) at 2:30 ratio, which might give me 15:1 odds if as I suspect the code swaps the ratio when calculating the results of combat ! I have to test this ; at worst, I lose two armies, and perhaps Porkbelly loses a few as well.

And this happens :

This sends Porkbelly in code-review mode. He finds the glitch, which is not the one we suspected. The chance of an attacker to win is calculated as :

%Win = Number of attackers / [Number of defenders + Number of attackers] The surprise : fortifications don’t do anything. I had 1 chance of 6 of winning, and rolled at 6 !

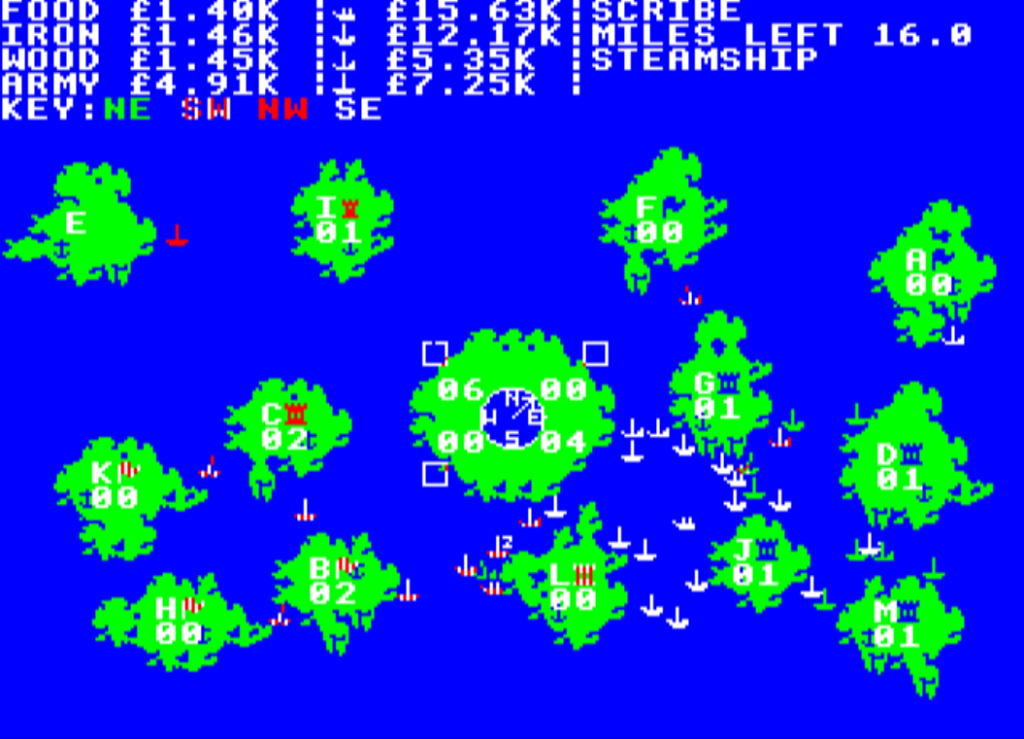

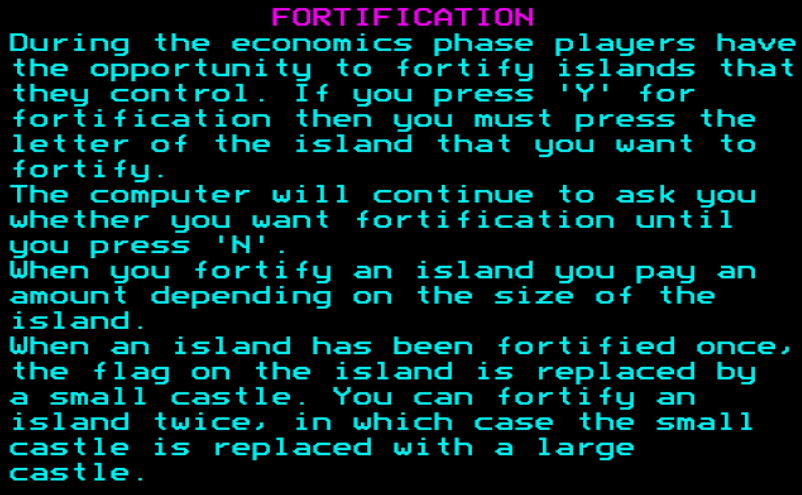

This changes everything ! All my fortifications are useless. Ahab happens to have amassed a lot of transport ships, and starts recruiting a large army. As for me, in all the excitement, I kind of forget the objective of the game is to be as rich as possible turn 11, and noticing Ahab’s transport fleet I build an armada of combat ships.

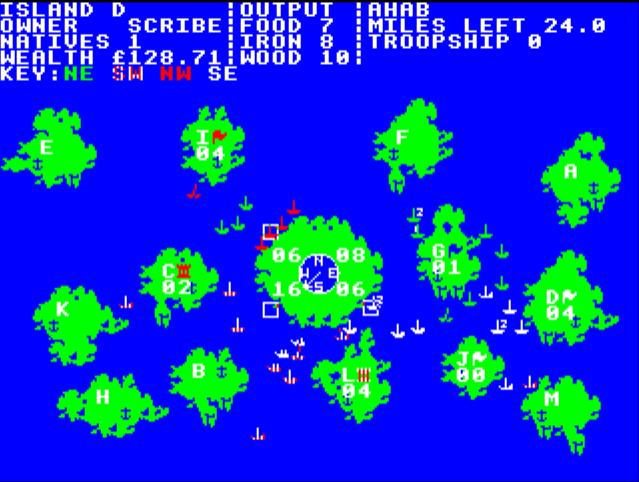

Ahab makes the first move, blocking once again the area between islands G and J and then capturing all the Eastern islands! Simultaneously, Porkbelly reclaims island L:

However, given the size of my fleet, I swiftly sink every one of Ahab’s ships and reclaim my islands back ! Our agreement from turn 2 included a provision that Ahab would maintain a garrison on island G, yet he used that garrison to attack me, so I seize that island too.

I manage to conquer all the western islands turn 10 except for island F which is only taken turn 11. That last conquest is useless, because no more revenue is considered after the economic phase of turn 11 so there is no reason to actually play the last two movement phases.

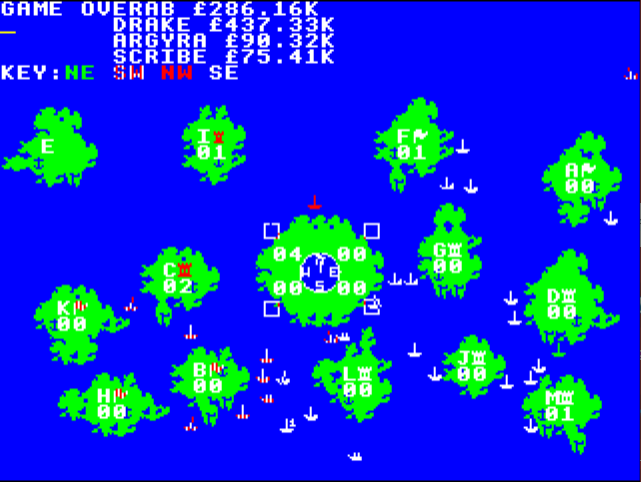

It is the end :

I lost, ending behind Argyraspide who had a major bug and could not build any ship. If I had not overbuilt, I would have passed him, but would still have ended far below Ahab. On the other hand, Ahab would have been better off, retaining the revenue from additional islands, though I am uncertain whether it would have sufficed for him to overtake Porkbelly.

I believe Porkbelly secured victory around turns 2 or 3 when Ahab underestimated my capacity to rebound and lifted the blockade. He later told us that he stopped purchasing anything after turn 6 and simply accumulated cash, an opportunity I never granted Ahab.

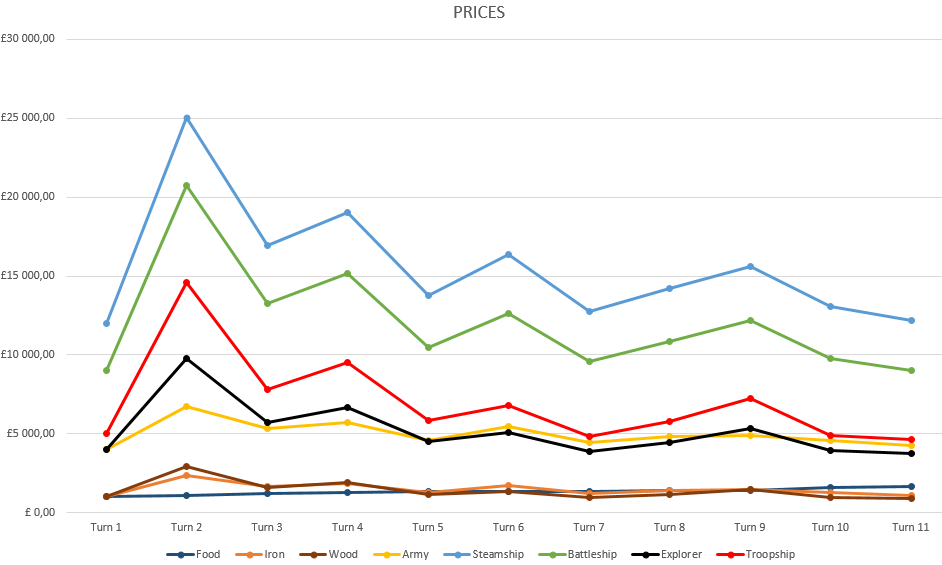

Argyraspide documented how prices changed during the game :

As you can see, the price of all the ships moved together, and I bought them at their peak turn 2. Ahab and Argyraspide were wiser.

That’s all for my side. If you want the point of view of the other players, you can read it on the forum thread where we have been commenting our game and sharing memes as we went along ; it also includes a lot of charts and data if you are into this. As for me, I will now move to the Ratings & Review.

Rating & Review

Islandia by Julian Gollop and Andrew Greene, published by Red Shift, UK

First release : Late 1984

Tested on : BBC emulator (BeebEm)

Total time tested : A bit less than two hours

Average duration of a campaign: 10 minutes by turn

Complexity: Easy (1/5)

Would recommend to a modern player : No

Would recommend to a designer : No

Final Rating: Flawed and obsolete

Ranking at the time of review : 44/88

Summary :

Islandia is Julian Gollop’s third game, and exclusively multiplayer. Its gameplay does not fit its naval theme, and the game’s unique feature—the economic system—has limited impact except for early mind games. Nevertheless, Islandia‘s unconventional starting setup (all players in the center, one turn apart) fosters a satisfactory multiplayer experience, albeit hindered by unintuitive combat calculations and obsolete user interface.

A. Immersion

Very poor. This is a dry game except for a funny introduction. As I will explain later, the ruleset does not even feel “naval”.

B. UI , Clarity of rules and outcomes

Poor. Adequate. The user interface is relatively straightforward, but the game suffers from several issues that detract from the enjoyment of gameplay for a contemporary player. The game uses a “pixel” logic rather than a “tile” logic (eg. you can go somewhere if all the pixels your ship is going to occupy are free), which was probably seen as advanced in 1984 but makes it difficult to determine whether a ship can maneuver past another. Worse, the game requires players to move their units in a specific order – a design flaw compounded by the lack of an in-game method to check which units will move next – so you cannot easily move ships out of the way. Together, those flaws create a subpar experience where whatever you want to do often fails for the wrong reason.

11/04/2023 Edit : You can actually postpone moving a unit, so the game is better than I gave it credit for.

I should mention here that none of us liked how combat results are calculated. It works as documented in the manual (except of course the fortifications not working), but the result feels unintuitive.

C. Systems

Poor. One of the most unique features of Islandia is how the prices of units and the revenue from island fluctuate depending on demand. Unfortunately, it does not work well. With only 3 raw resources determining the price, the price of all units tends to move together so the price changes cannot be leveraged strategically but just incurred passively.

The rest is more classical for a modern player, though certainly also unique by 1984 standards. My main gripe is that the combat rules do not fit the theme of the game : attacks end the turn of the attacking ships, creating the kind of frontlines you would expect more in land warfare. Likewise, the staples of naval wargames are poorly represented : you don’t need to explore the map (explorer ships only reveal the wealth of an island and its native population, information which immediately becomes public) and you don’t need to ferry the production of your islands back to your metropole, though as an undocumented feature you can blockade a port with a warship to stop it from generating revenue, something we discovered late in the game.

What redeems the game is another distinctive feature of Islandia : the starting positions. In most other games, players start far apart and get closer as they expand. In Islandia, players all start in the middle and can interact with one another in the first movement phase of the first turn – I don’t know any other game doing that. Alas, it comes with an obvious issue that should have been fixed somehow : spawn blockade- anyone playing Islandia regularly must have had house rules against it.

D. Scenario design & balancing

Very poor. No AI, but at least the game generates random battlefields and let you accept or refuse them.

The 4 players are not equal, and the order of play has a decisive impact :

- The players playing first and second have a first-mover advantage allowing them to blockade the enemy ports or, less dramatically, position their ships in front of the other players in order to win the initial island rush,

- On the other hand, the last players can take enemy islands without fear of retaliation just before the income is calculated – even if is lost immediately afterwards.

E. Did I make interesting decisions ?

Yes, every turn , because with two players breathing on your neck and a huge freedom of movement for your ships you have no other options.

F. Final rating

Flawed and obsolete. Islandia‘s unique economic system falls short of making a significant impact, leaving the game as a sort of Colonisation-ultralite experience. However, Islandia still creates an effective multiplayer experience due to players being in range of one another from turn one. A solid effort for 1984 – especially from a designer not yet 20 – the game aged poorly due to mediocre UI, allowance for cheesy tactics and a lack of commitment to its theme (e.g., frontlines, no naval routes, etc.) – and that’s before accounting for the bugs. I liked the unique challenges I faced, but there was just too much friction and too many issues to play another match.

If I understand correctly the timeline, Islandia was released after Gollop had left Red Shift, following pretty much all the other developers. It seems likely to me that Gollop and Greene either rushed the game, or even did not finish it at all ; this would explain the missing code for fortifications and why some features are totally undocumented.

Maybe the next multiplayer Gollop game I will play, Nebula, will be different ? I will report soon !