[ZX Spectrum, CCS]

I am a bit slowed down on my regular schedule at the moment, and when I’m in that situation I pick from the seemingly endless list of Spectrum wargames, and so I am happy to present you CCS’ War Zone.

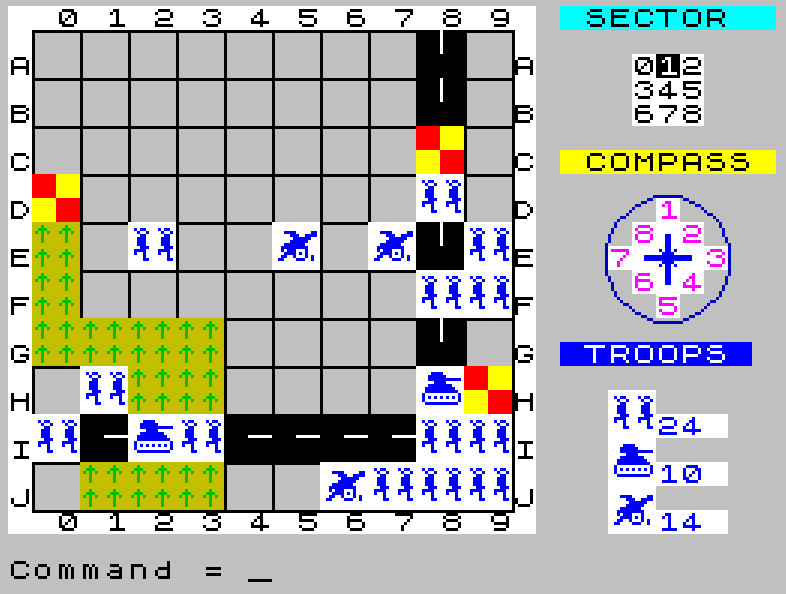

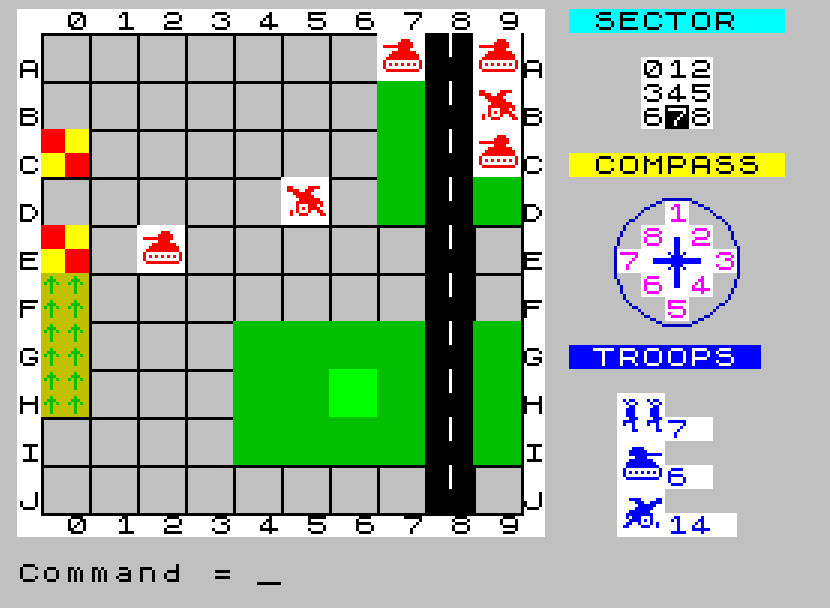

After asking you how many units you want in your battle (from 15 to 150) , War Zone opens a 9×9 grid map featuring open terrain (in grey), roads, hills (in green, with a brighter green for the hilltop) and forests (in beige with arrows) – without forgetting the occasional mines (in red & yellow).

The opening map is only one of 9 sectors, and I can only inspect those sectors in which I have a unit.

Both sides start with the same number of units and the objective is either to completely clear the enemy home sector (top-left for me, bottom-right for the computer), or achieve a 3:1 ratio in terms of units.

There are three units available:

- Infantry move fast (5 squares/turn on road, 4 squares on other terrains) but can only fight in melee,

- Tanks are slower than infantry (4 on roads, 3 squares in open terrain, 2 on hills, 1 in forests) but can attack at a range of 2,

- Artillery are the slowest (3 on roads, 2 in open terrain, 1 anywhere else) but they have 3 in range;

Terrain has some impact on the game: hilltops give +1 range to tanks and artillery, and units in forests are totally immune from ranged attacks. The impact of the latter bonus is compounded by the fact that units attacked at range that are missed can return fire – but of course they can’t if their attacker was in a forest.

The border between sectors does not block movement, but it blocks ranged attacks, so for now I move my units in disputed sectors in the forest while the reinforcements stand ready to cross in the next turn.

The turn is ended by one air attack against an enemy unit in sight, and then the computer gets to move its units.

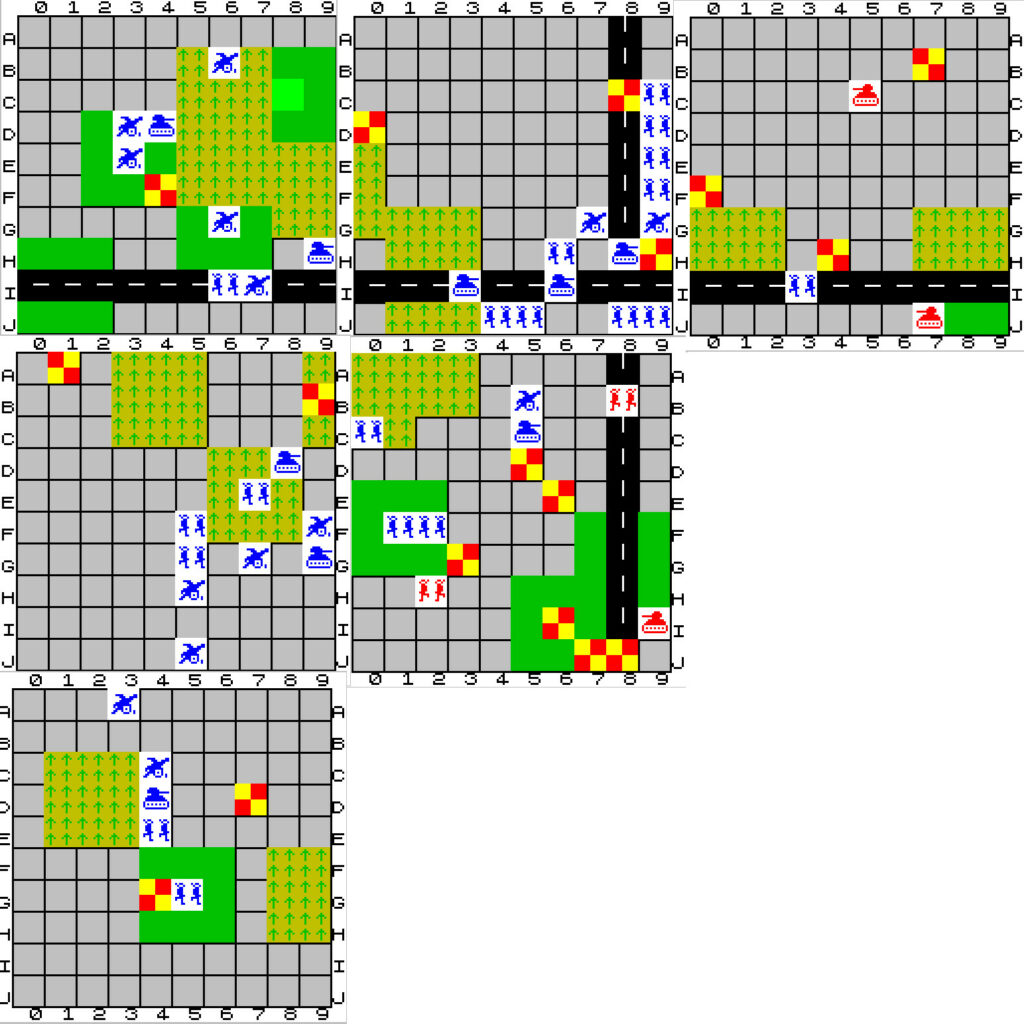

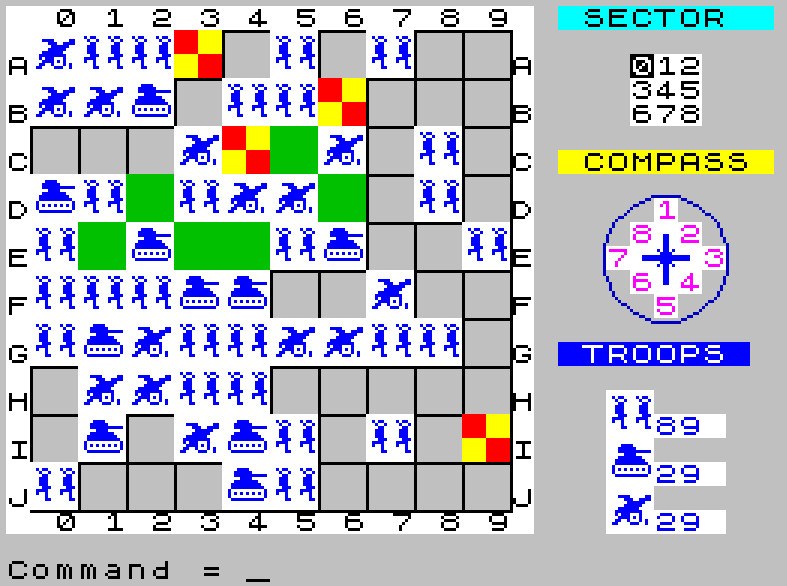

The bulk of the enemy push is in sector 4, with sectors 2 and 6 only receiving meagre reinforcements:

Tanks and artillery can both move and attack, so by the end of turn 6 I have cleared sector 6 and gained a strong position in sector 4.

I won’t get into a blow-by-blow account of the battle for sector 4. The enemy pours reinforcements there every turn, but its attacks are hampered by the road: according to a weird game rule, leaving a road ends movement for the turn. This protects me from infantry rushes, and then I counter-attack at range (around 50% kill chance every attack) and then finish off the rest with infantry attacks of my own.

By the end of turn 5, I have cleared all my starting sectors and the enemy refuses to attack. A scout sent to sector 7 reveals that the enemy is waiting for me there!

I regroup my forces to assault sectors 5 and 7, but by the time I actually attack, sector 7 is devoid of enemies, and the ones I find in sector 5 are retreating.

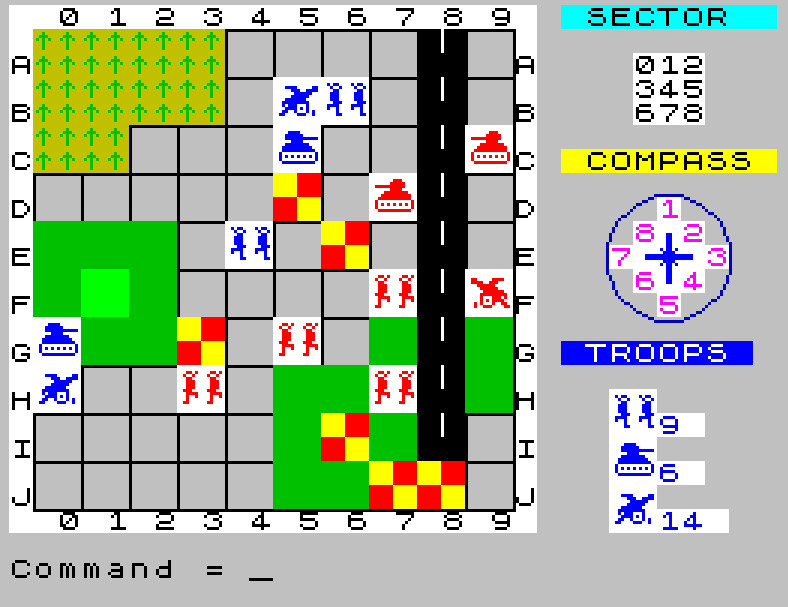

I surround sector 8 for the final assault:

I attack from the West and immediately occupy the hilltop to gain a range advantage…

… but I did not need to bother so much. When the enemy is down to 6 units (against 20 of mine), I win immediately as per the 3:1 victory rule.

This took a bit less than 2 hours that I did not find very enjoyable.

Ratings & Review

War Zone by Steve P. Thomas, published by CCS (UK)

First release: November 1984 on ZX Spectrum

Genre: Combined Arms Tactics

Average duration of a campaign : Around 2 hours with 50 units

Total time played : Around 2 hours

Complexity: Low (1/5)

Final Rating: Totally obsolete

Context – We already know Cases Computer Simulations (CCS) and the “Cambridge Award” it organized. With wargames being both the winner and the runner-up of the first 1983 edition of the award, it is no surprise that the second edition saw the submission of a good number of wargames. However, the winner of the 1984 edition was The Prince, a multiplayer RPGish adventure game that looks fascinating on its own right. Still, 2 of the 4 runner-ups were wargames: Insurgency (on my to-do list, even though it is multiplayer only) and today’s War Zone by Steve Thomas, which was also released on Amstrad CPC.

I was not able to find any information on Steve Thomas given the ubiquity of his name, but according to SpectrumComputing he developed three historical wargames for CCS in the early 90s: Avalanche, the Battle of the Bulge and Crete 1941. Maybe I will reach them.

Traits – I believe my AAR conveyed how stale War Zone is. War Zone is exclusively about killing enemy units, which is rarely great design to start with, and the lack of unit diversity compounds the issue. The terrain ruleset could have saved the game, but didn’t:

- forests immunize units from ranged attack, but what’s the point when the combination of short range and high infantry speed allows infantry to move in one turn from “out of range” to “currently stabbing you with bayonets“.

- hills with their extra range could have allowed to attack units safely, but you can only put one unit per hilltop, for a marginal +1 range bonus, so they have no strategic impact

- roads are the only terrain to have some impact, not due to the small speed increase but because they act like rivers do in other games: they take time to cross. I don’t think that was intended.

What I probably did not convey properly is how tedious the UI is. The game lets you generate up to 150 units at start, but that must be hellish to manage. To select a unit, you need to input its coordinates; to shoot at something you need to input its coordinates AND the coordinates of its target. There is no pointer to move over the screen, and no input to say “next unit”. To add insult to injury, the game does not indicate which units have already moved or fired (it can be done “separately”). This turned an inoffensive game into one I did not like playing.

At least, War Zone is technically solid (no crashes), and does have a computer opponent, an uncommon feature on the Spectrum.

Did I make interesting decisions? No, beyond “get there with the mostest“; being there the fastest is not even required.

Final rating: Totally obsolete. War Zone feels so generic that it could have been generated by an AI, if vibe coding with AI existed in 1984.

Ranking at the time of review: 127/168

Reception

Much to my initial surprise, War Zone received a good-to-excellent reception, with Angus Ryall from Crash (and Games Workshop) calling it in the January 1985 issue “an impressive game, certainly the best wargame that C.C.S. have released so far.” and later “The second best computer wargame I’ve ever seen”. I suppose it was the best non-Games Workshop game he had ever seen.

Other reviews are positive and consistently recommend the game, though none as enthusiastically as Ryall did:

- John Conquest in Big K (January 1985) gives it the maximum score (3/3): “Good, clear graphics, smooth action, simple and straightforward control systems. Not for the hardened wargamer, but good fun in the true Wellsian spirit.”

- Mike Singleton himself praised the game in Computer & Video Games (April 1985): “Those of you who like strategic problems, without [the] distraction of massive tactical fuss and detail, I can recommend War Zone highly.

Similar variations of “overall a good game if you like the genre” can be found in Home Computing Weekly , TV Gamer, Amstrad Computer User or Micro Adventurer; I could not find any negative review.

Generally speaking, the reviewers praise the simplicity of the game, complain about the same UI issues I did and about the lack of multiplayer. They also have mixed feelings about the speed – some find the computer fast, others slow; I surmise it depends on the number of units they played with. Now that I think about it, I should have expected War Zone to be well-received. The offering in wargames for the Spectrum was terrible, and War Zone proposed a staple that did not exist. After playing Order of Battle, I could never return to Panzer General; but when Panzer General IIISE (I did not start with the first one) was all I had, you can bet that I played it in & out. To an extent, War Zone is the Panzer General of British 1984 wargamers.

On an unrelated note, I had planned to cover Julian Gollop’s Battlecars as a BRIEF to have a 100% Gollop coverage. Unfortunately, Battlecars is a full-fledged game that deserves a lot more than a BRIEF. It’s not a wargame, and I can’t give it a proper coverage, so I’ll simply skip it – Gollop apparently only worked on the car editor anyway, so that’s acceptable.