[DOS, Avalon Hill]

As some of you know, I work in video games, and as such video game trivia is an important part of office conversation. Writing this blog and lurking on the ones of other chronological gamers has given me significant capabilities to one-up whatever my colleagues bring to the table (“akshually“, or rather its French counterpart “alors en fait“) or to look jaded when someone mentions a design innovation (“it’s not that innovative, a game did it in 1982“). Unfortunately, I work on mass-market video games, so the chances to flex obscure knowledge on wargames are rarer than I’d like. That should change now that I have discovered Incunabula, which grants me a trivia on a mainstream game: there was a Civilization-type game before Sid Meier’s seminal Civilization. My colleagues won’t hear the end of it – until they mute their Slack channel, that is.

Several sources (including Wikipedia!) claim that Incunabula is a port of Avalon Hill’s 1980 Civilization boardgame. There are several hints making this believable beyond simply a common theme: Incunabula borrows several systems straight from the boardgame and it was published by Avalon Hill in 1985. However, it is not true: Incunabula had been first released independently by Steve Estvanik (to whom we owe Ram!) in early 1984, and only then picked up by Avalon Hill. Let’s see now what the game is really about.

Turn 1

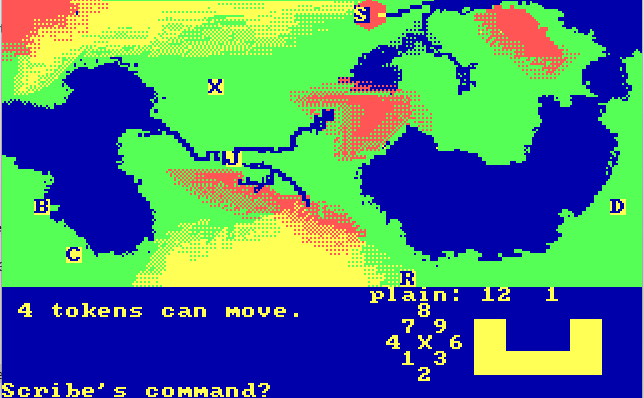

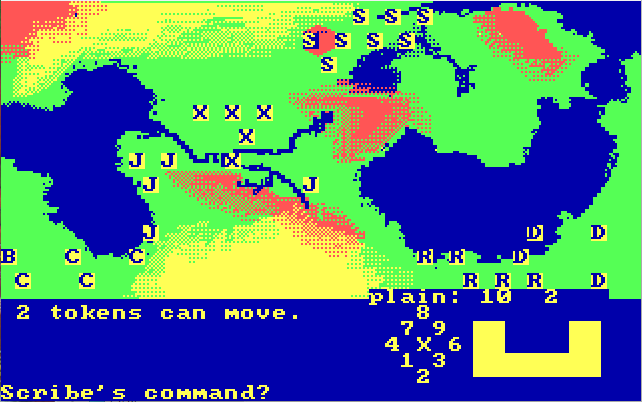

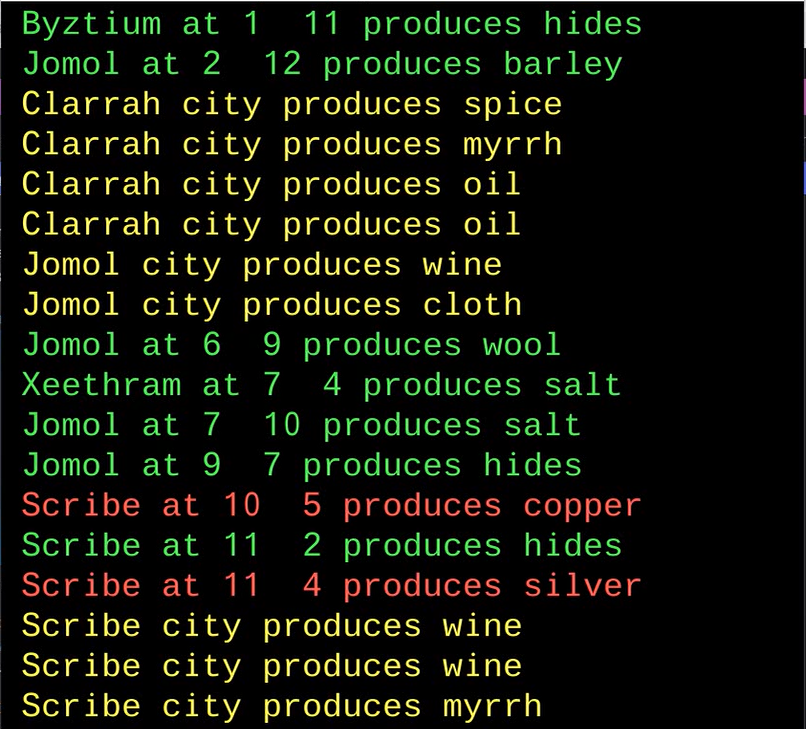

My civilization, the Scribes, start in the Northern part of the world, between a river and the desert. I have no immediate neighbours and large area to expand in my East; overall a good start.

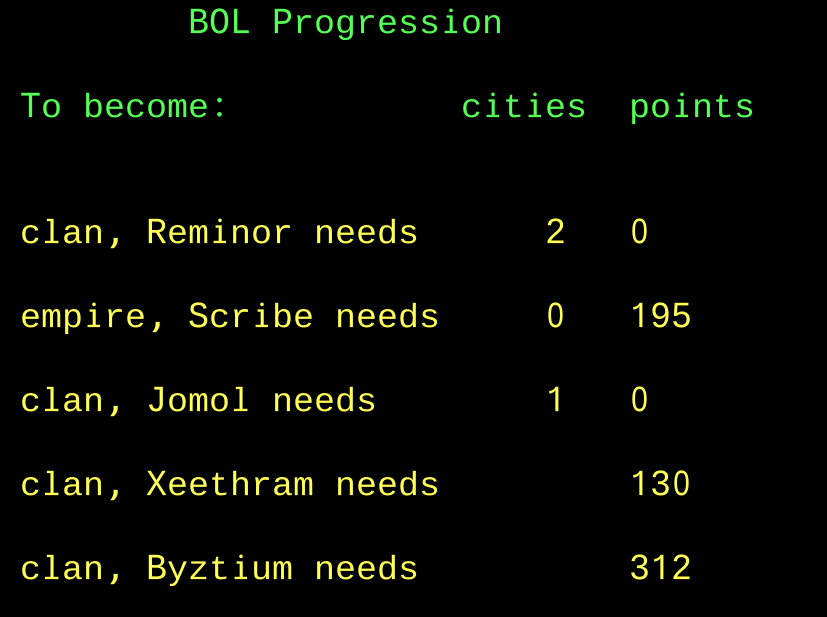

Unlike Civilization, the only way to win in Incunabula (for non-Khan players, more on this later) is to achieve two objectives simultaneously:

- finish the research tree of your “basis of law” – also something I will cover later,

- build an Empire (own 5 cities and a certain number of progression points).

With no starting technology and a starting population of 4, I am still a long way from that. My first objective is to grow in population, and grow fast. There is no reason initially to have more than 1 population chit by hexagon: each plain or river tile produces an average of 25 “grain production units” (gpus) irrespective of the number of population chits occupying it, and each of these chits consumes 6 gpus every turn (they’re stockpiled between turns), so for now I just spread out as much as I can.

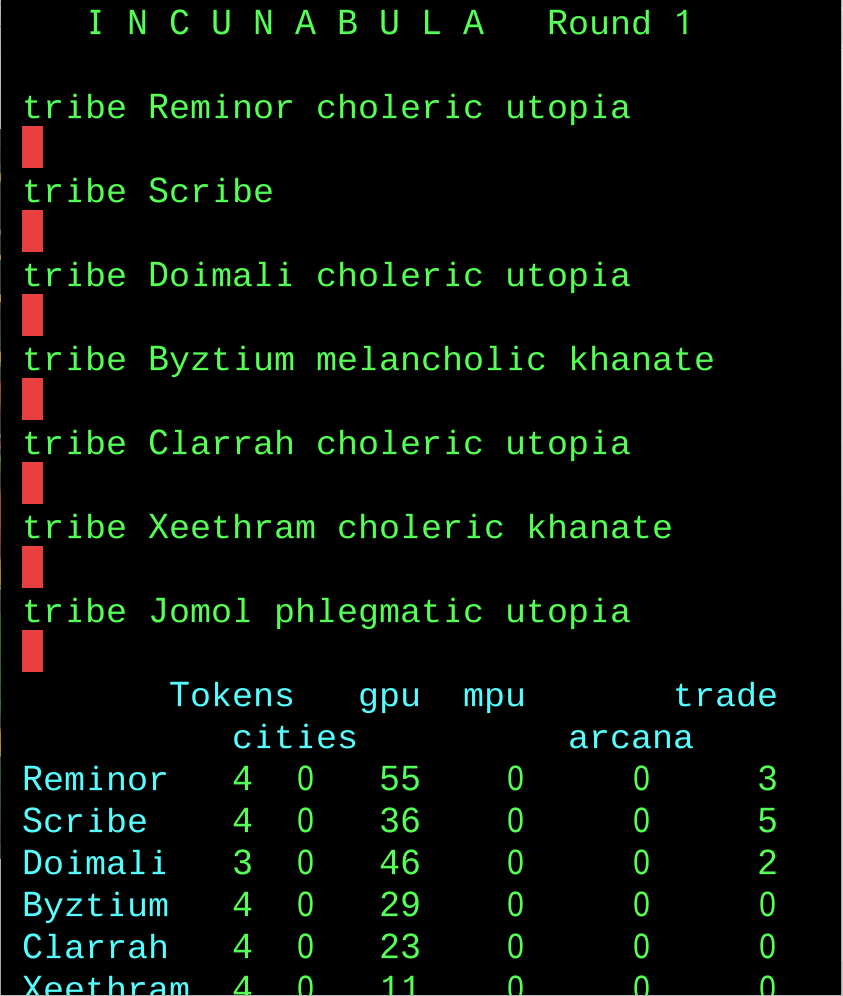

That’s already the end of the first turn, and I get to know my neighbours for the first time. They’re bad news.

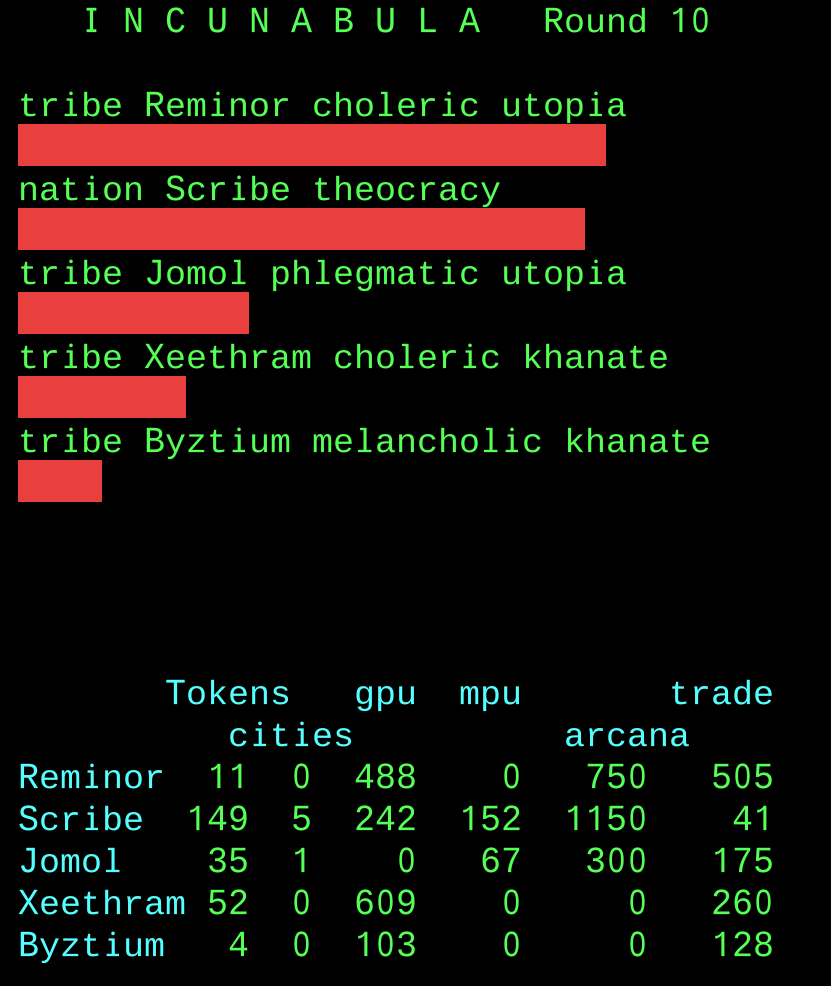

Civilizations in Incunabula are defined by their humor (=personality) and their basis of law; human players only have the latter. The four humors are:

- Choleric: these opponents want to be first and will optimize for this. They are theoretically the most dangerous opponents,

- Phlegmatic: these opponents want to be top-3, so they are more likely to remain in an alliance until the end, provided the alliance is with a strong player. Unintuitively, they are described as players who retaliate to attacks, unlike choleric players who only retaliate if it advances their position,

- Melancholic: those players are the kind that all veteran gamers hate: they’re don’t really want to win, they want to balance the game and make it last forever,

- Sanguine: chaos agents in terms of behaviour, but there are none in this game,

Until I get to choose mine, there are only two basis of law represented in this game: khanates are the best fighters, but they can’t research and have a slow population growth, whereas utopia are the opposite: worst fighters in the game, but high population growth and high production.

With four choleric players, this game is going to be a crab basket. I am also worried that my Xeethrami neighbours are khans – these are aggressive players whose unique victory condition is to take a lot of other players’ stuff rather than build an Empire or do nerd research stuff. We’ll see.

Turn 2

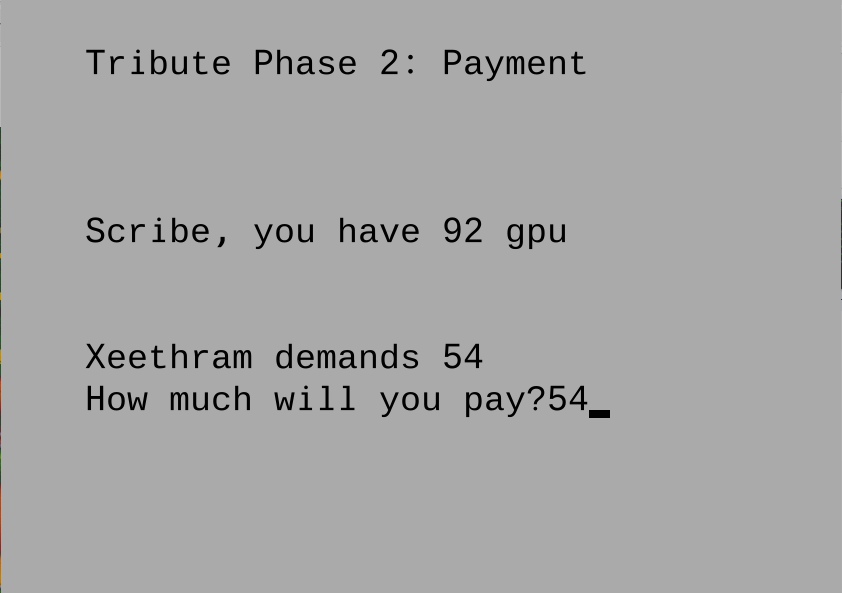

The second turn starts with my neighbours trying to extract a tribute from me. They’re too far to be a threat, so I send them packing.

Very little happens during this turn. Each of my population chits generated a new one, so I reached 8 in population. All the extra chits are sent to occupy new tiles. The other players are less efficient than I am at this, and the first battle occurs between the Byztine Khanate and the Clarrahians far in the South-West.

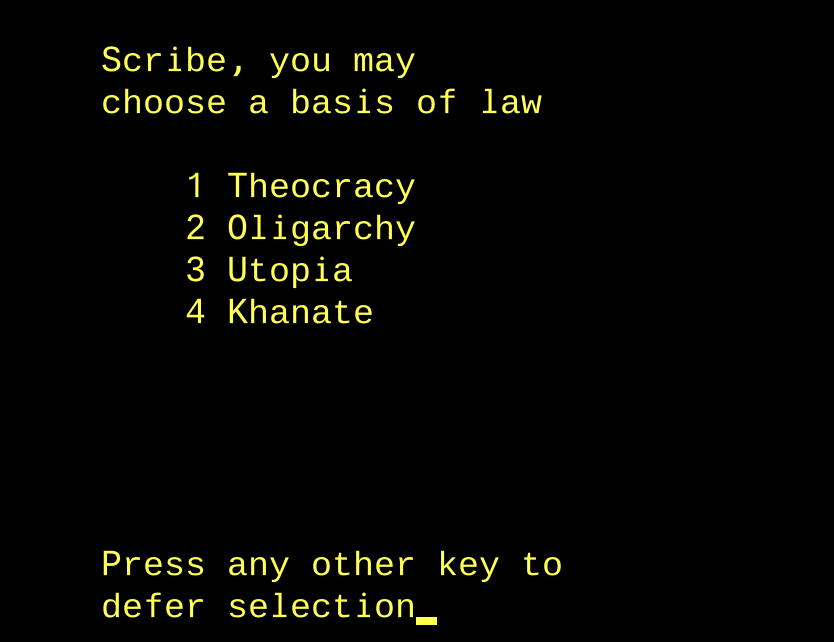

The most important event of turn 2 happens at the end: I get to choose my very own basis of law!

I already explained Utopia and Khanate, leaving Theocracy and Oligarchy to explain:

- Theocracies fight well, but suffer from higher population maintenance cost in GPU, smaller production and smaller population growth; they’re the most similar to the Khanate, but with research and normal win conditions,

- Oligarchies also fight well, though not as well as theocracies. They also have a higher population maintenance cost, but nobles like luxury so production is high. Their population growth is also good.

I choose Theocracy – I will have to fight against the Khans soon, and population growth should not be an issue given the size of the territory I will be able to control anyway.

Turn 3

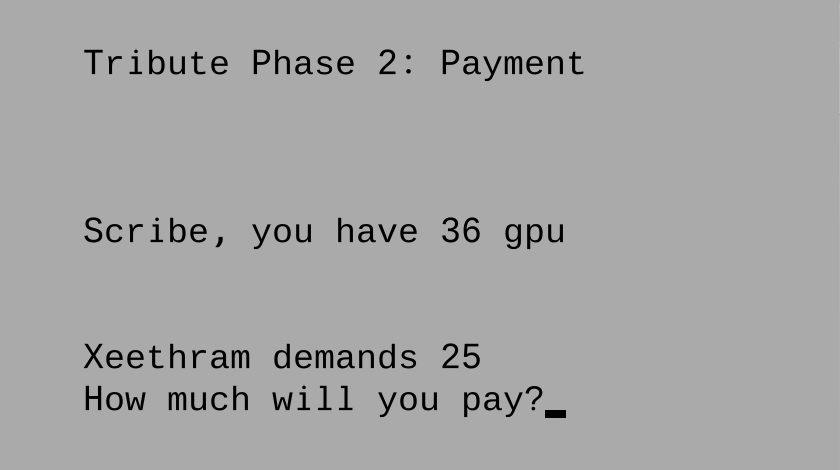

At the beginning of the turn, I receive another visit from the Khan for a tribute. They tell me they are quite prepared to fight, unless I pay them cash to go away. For now don’t have the time to fight them indeed as I want to expand East, so instead I puff and look important – and then pay them gpus to go away.

My choice absolutely pays off. The Xeethrami expand South against Jomol, and I can grow peacefully, taking control of several mountain hexagons which generate metal production units (mpus), whose only purpose is to make soldiers fight better – but I crave for that!

Turn 4

At the beginning of the turn, the Khans come back to me about their geld. This time, the amount they request is eye-watering, so it’s a no. I have, after all, more than 30 in population and the Xeehrami are also facing Jomol. I should be fine.

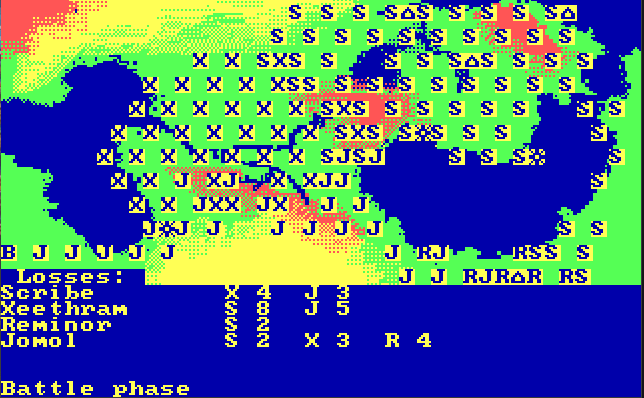

Unlike Civilization, Incunabula does not have dedicated combat units. Instead, attacks are executed by moving population chits into enemy territory – combats then being resolved at the end of each of the two impulses.

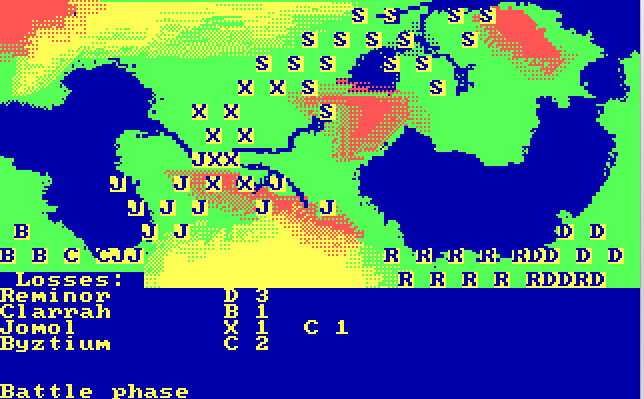

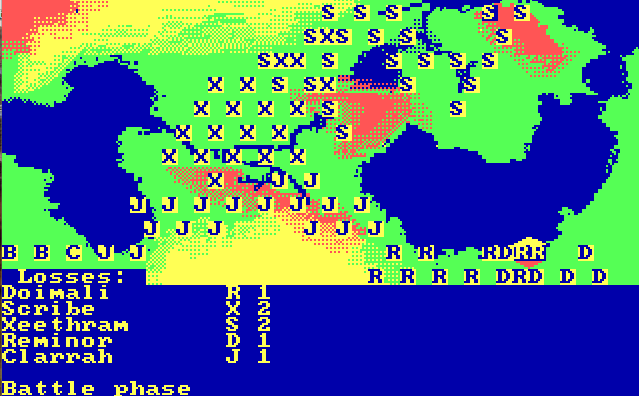

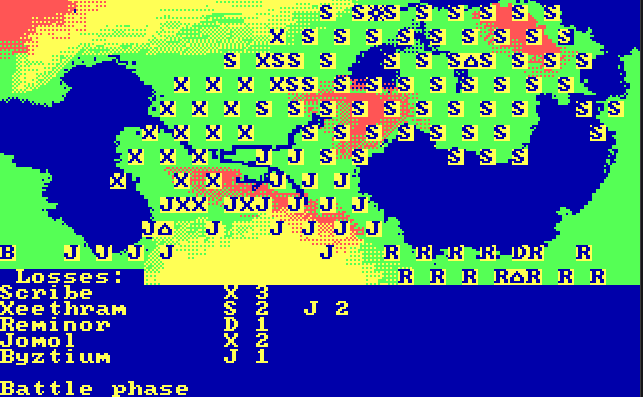

Unfortunately, Khanates are martial civilizations. Despite fighting them at 2:1 ratio, their losses are marginal: none in the first impulse (2 losses on my side) and only two in the second impulse (2 more on my side). Overall, the Khan expands its territory as much as I did this turn.

I also (automatically) start to produce trade goods this turn, but not enough to do anything with them yet.

Turn 5

On the ground, it is a fairly standard turn, with battles on the border with the Khan, and expansion in the East.

I warfared a bit better this turn, but the border between Xeethram and myself did not move much – and it won’t in the following turns either. True, with my massive population growth I could now push aggressively, but the game does not reward aggression and I prefer to use my extra population to found cities. These require 6 population in a plain (more in a mountain) and eat 40 gpu each, so I can’t afford them and megastacks on the border for now.

Turn 6

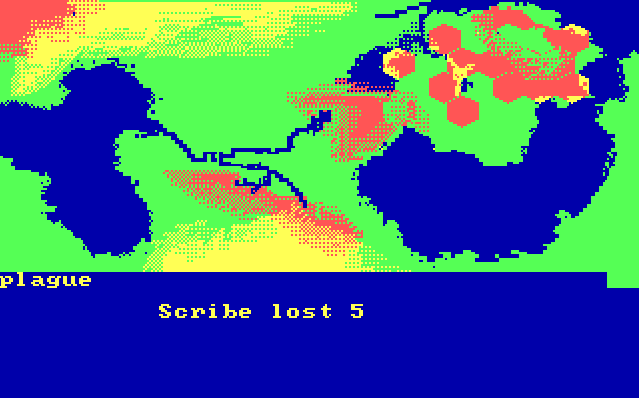

I am hit by a plague at the beginning of the turn, which slows me down somewhat, but I am still net positive in population. The same turn , I found my first city at my starting location. It will produce special trade goods.

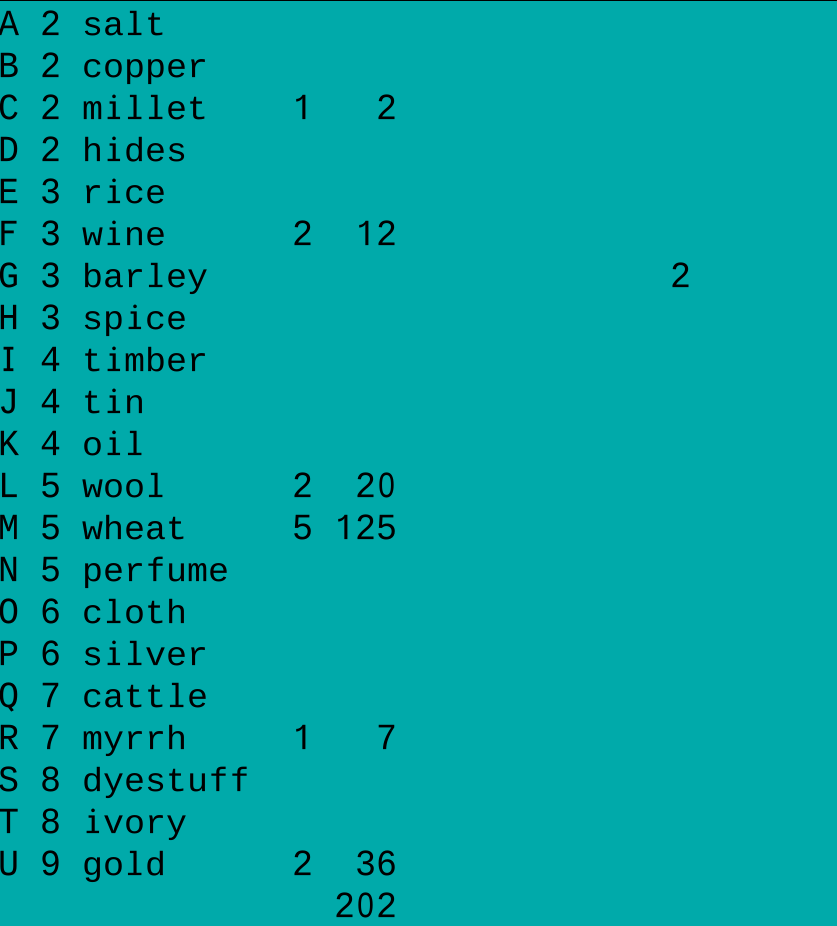

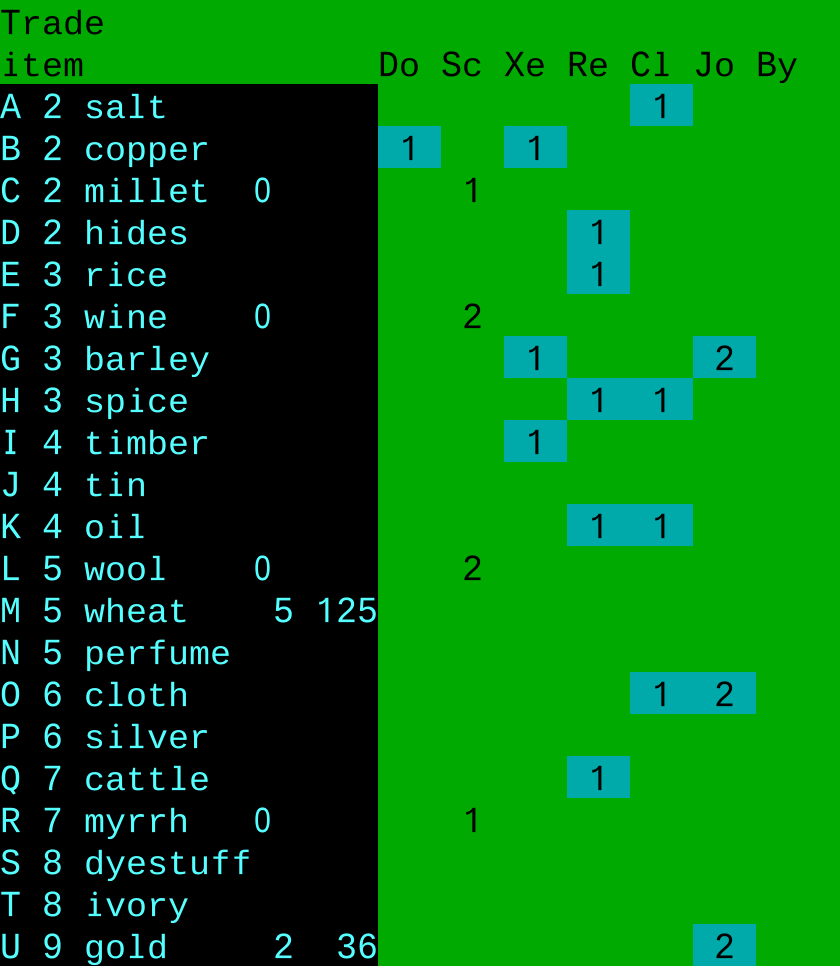

What’s more interesting is that my production in trade goods, started in turn 3, is getting significant. This is one of the most important parts of the game, so let’s explain the feature a bit:

- At the end of each turn, each occupied hexagon has a chance to produce a trade item. The exact trade item depends on the nature of the hexagon and whether it is a city or not.

- Trade items generate a trade value according to a calculation pulled straight from the Civilization boardgame: Quantity² x Trade item value.

You can have any number of any item, but can only store up to 6 from one turn to another

- The player can then trade with other players. Each player in turns offers what they are willing to trade out, and the other players come with what they’re willing to pay for that:

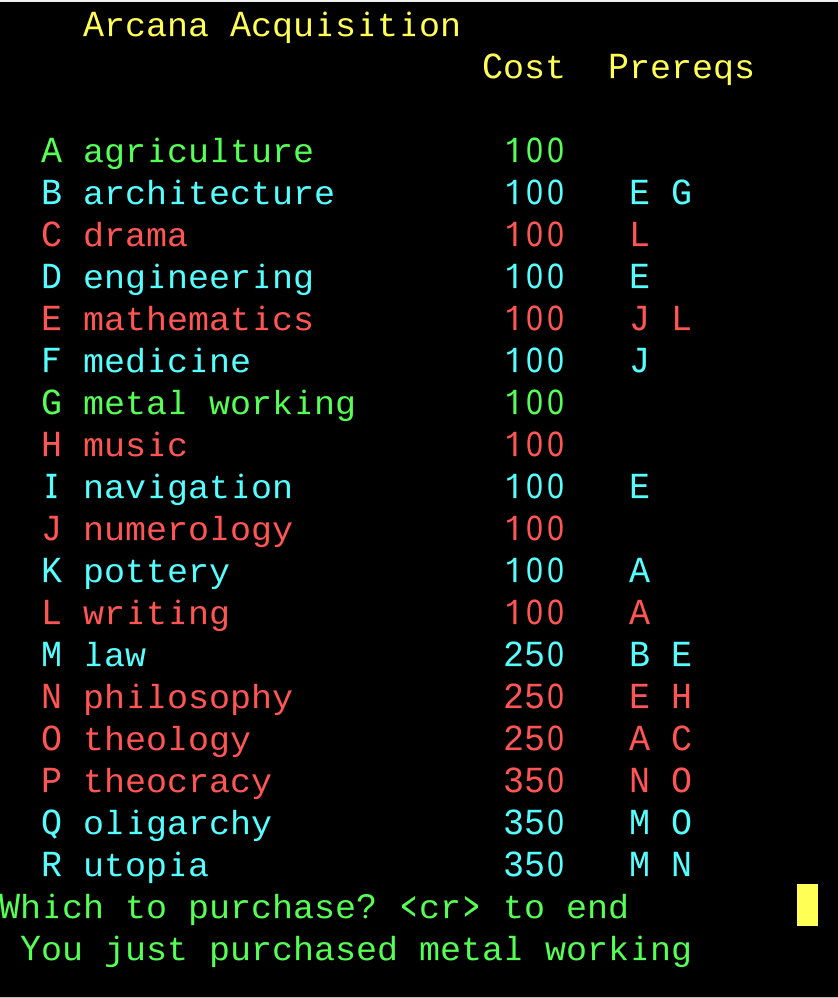

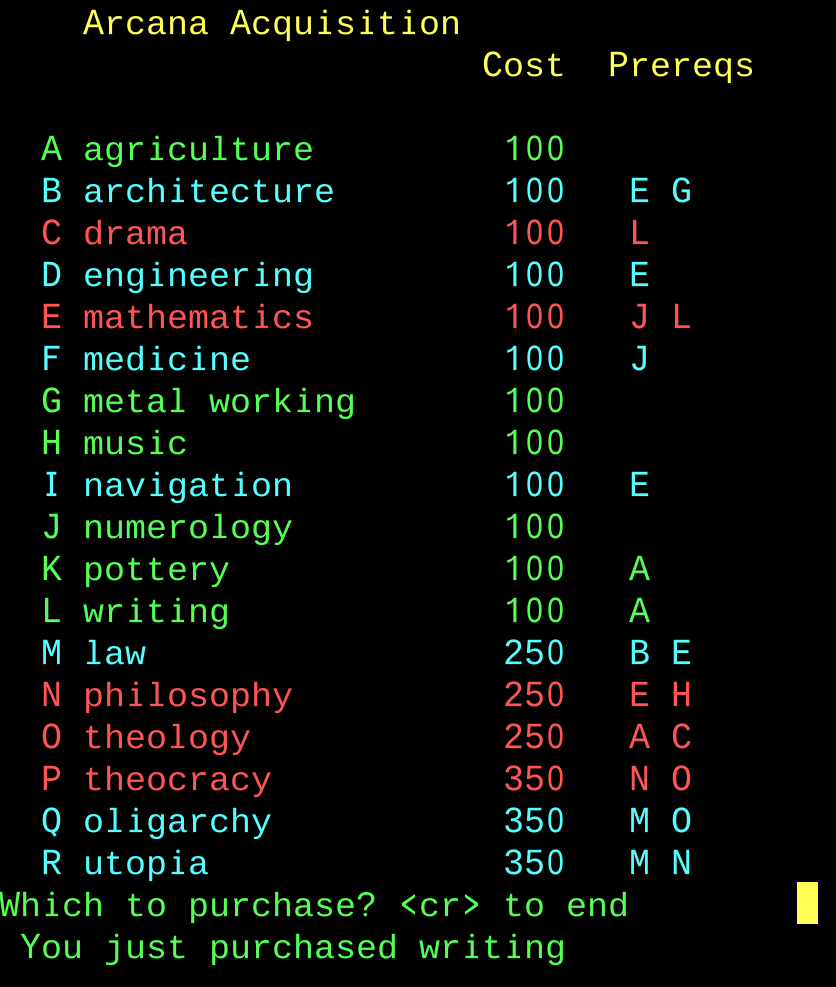

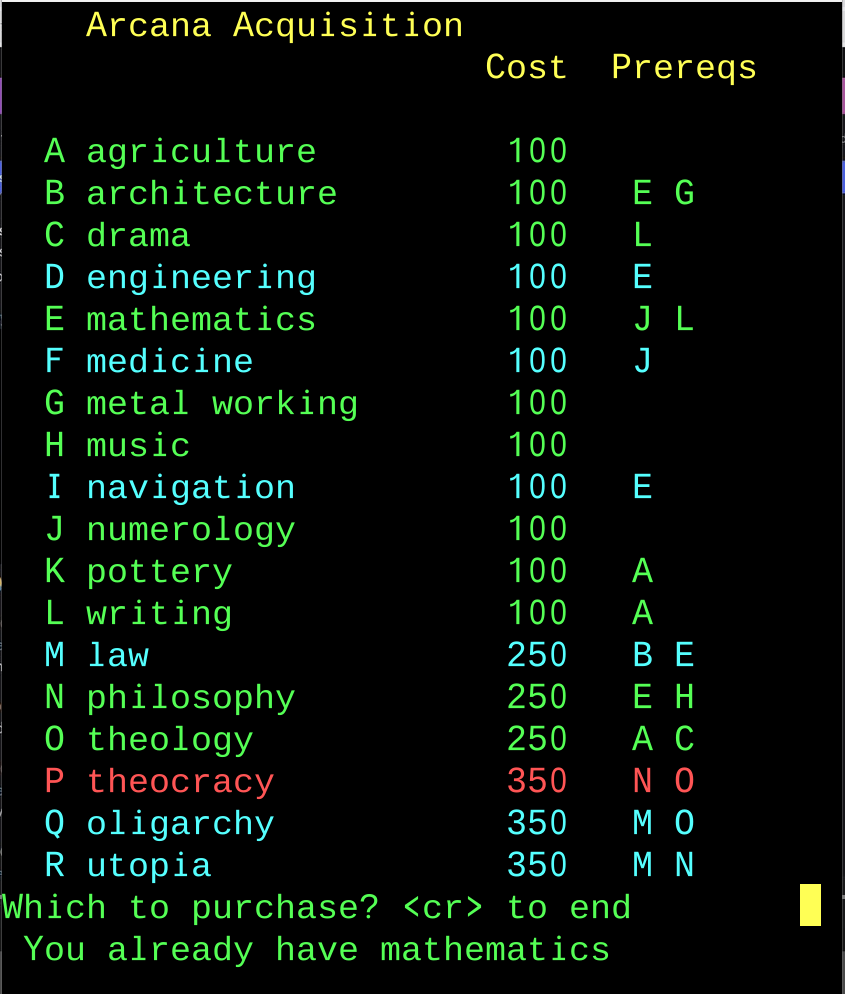

- Finally, with the trade points , the players can buy technologies (called Arcana in game)

For now, I buy metal working (which improves combat capacity) and agriculture (which has no effect except as a prerequisite for other techs I need).

Turns 7 to 9

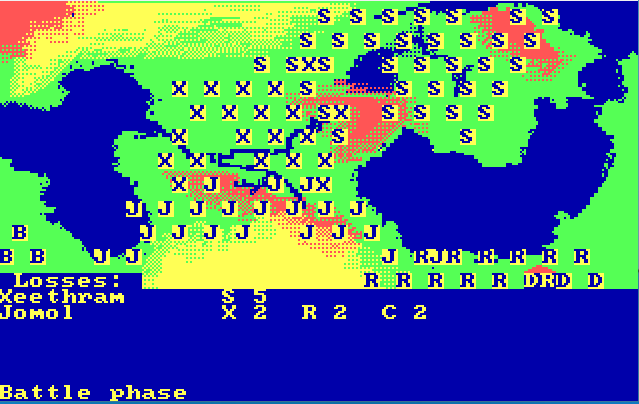

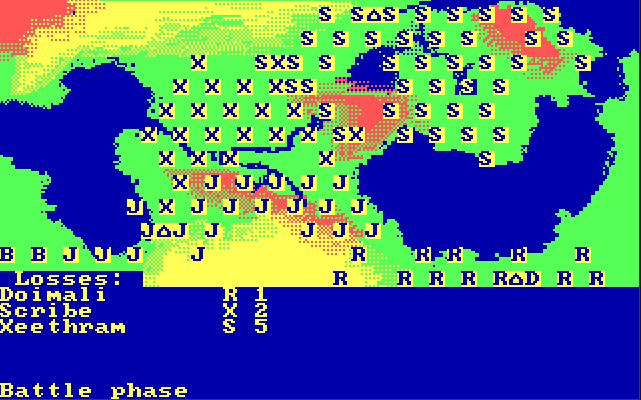

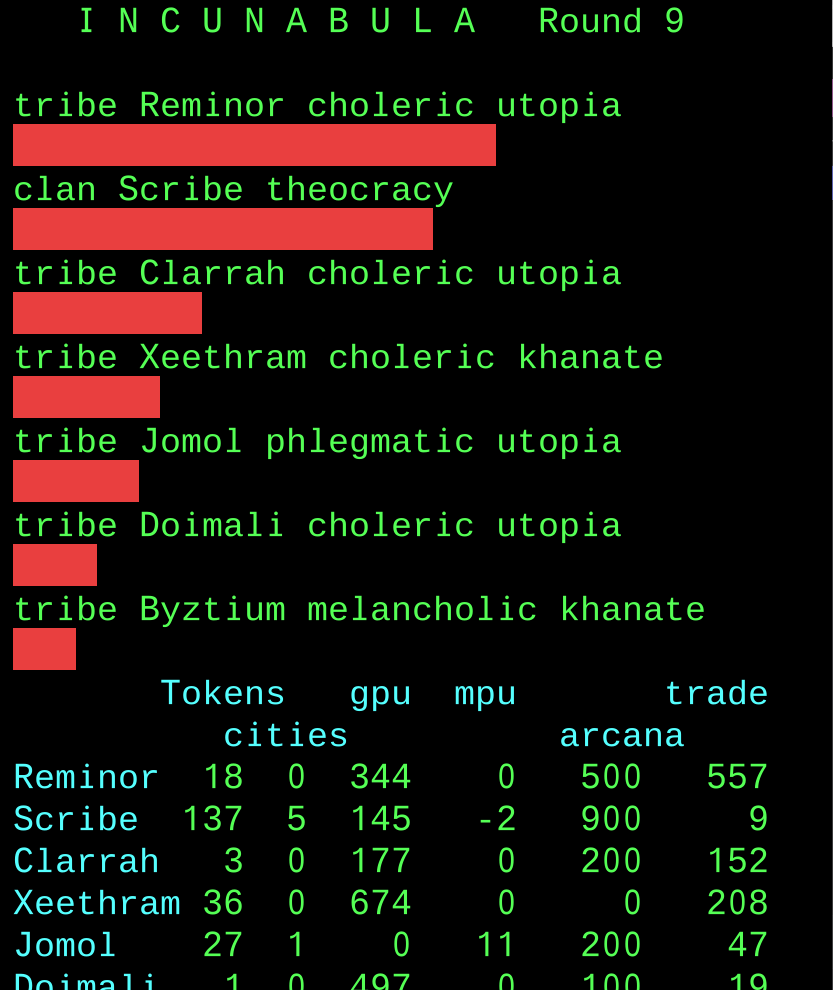

There isn’t a lot to say about those turns. I carried on expanding East, until occupying the complete peninsula. The permanent war against the Xeethrami never abated and the border never moved, though the Xeethrami managed to expand South and North-West. In the mountains South-West of my empire, the Jomolians replaced the Xeethrami, but it does not change anything for me strategically.

Meanwhile, my trade goods generation is incredibly high. No one wants to trade with me anymore (I surmise that it is because choleric players don’t like trading with the player in the lead) but I can still buy technologies using my production alone.

Thanks to my growth in points (the accumulation of Arcana and Trade Points) and number of cities, my civilization got upgraded to the status of “clan” – I am in the lead with Reminor in second place.

I don’t think the Reminorians can catch up, but I don’t want to take any risk and I cross the large river: if I can force them to fight me, they won’t be able to buid cities easily.

Turns 10-11

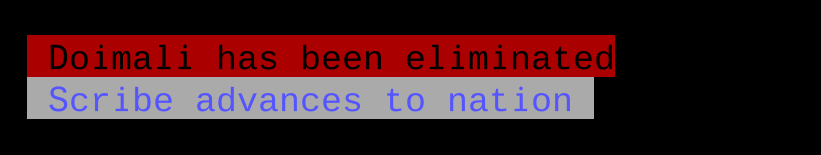

The general trends of the previous turns continue. The Doimalites finally disappear just as I become a “nation” at the end of turn 10.

I am now a few points away from the final status: Empire.

Reminor is still a “tribe”, but that’s only because they don’t have cities – which are easy to build. Once they have one, they will immediately jump to Nation as well!

It will be too late for them though:, because unlike them I am also one technology away from getting the theocracy arcana, which is the other condition necessary to win.

I also start engaging them in the South-East; if I kill enough of them they’ ll never be able to build their cities.

Turn 12

At the beginning of the turn, I advance to Empire. Jomol suddenly takes the second place by advancing to clan.

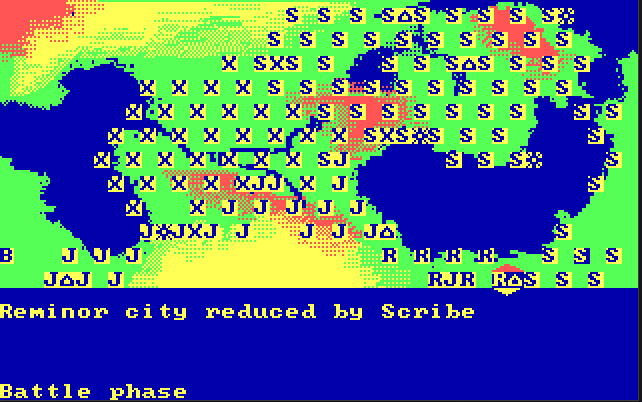

I use the turn for a last push toward the Reminorian’s only city…

…and I take it just as the turn closed.

This was the cherry on top. I research the last arcana and win the game.

This was an interesting game that took around one hour and half, but I don’t feel I was ever challenged. My test game was similar to this game, though the beginning was a bit harder (I started sandwiched between 3 other civilizations). Incunabula does not have any rubberband system to slow down a player with a population lead, so once that is achieved against the computer (which does not try very hard to grow), the game is effectively won.

However, I am curious to see how it plays in multiplayer, and I am organizing a 6-player PBEM game! We still have a few slots, so if you are interested in joining, email me!