We carried out the first decolonization up until last year. Now we are about to begin the second. After granting independence to our colonies, we are going to take our own. Western Europe has become, without even realizing it, an American protectorate. The task now is to rid ourselves of their domination. […] American capital is penetrating French companies more and more. One after another, they are falling under American control. It has become urgent to shake off the general apathy and set up mechanisms of defense. The Americans are in the process of buying up the French biscuit industry. Their advances in electronics are staggering. What will prevent IBM one day from saying, “We are closing our factories in France because the interests of our company demand it?

Charles De Gaulle, 4th of January 1963

We ended our last article about early French computing in 1952 – before much computing had been done, really. The CNRS-led Couffignal machine found itself unable to deliver a computer, not because they had realized they had pigeonholed themselves into a technological dead-end, mind you, but because the company in charge of building the technological dead-end had gone bankrupt. By 1950 already, the French labs (particularly the military ones) had grown increasingly uneasy with this whole Couffignal project and started looking for a private solution for their computing. Two French companies would answer the challenge in the mid-50s: an old company called La Compagnie des Machines Bull, and a “start-up” before the word existed: the Société d’Electronique et d’Automatisme.

The Leader: Bull

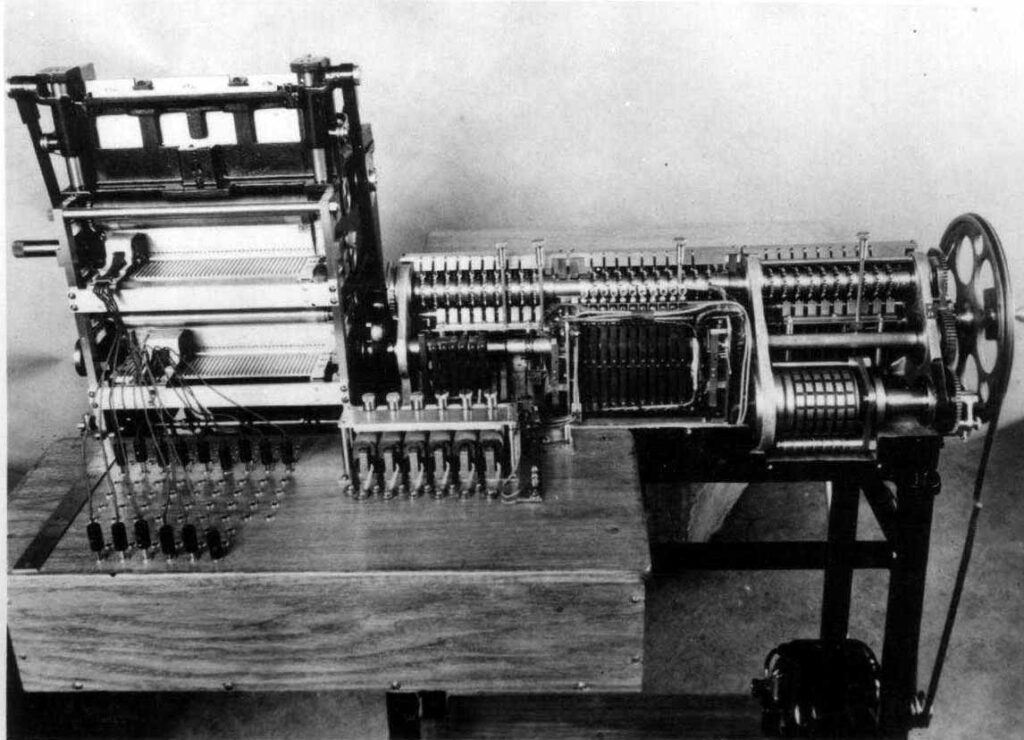

La Compagnie des Machines Bull (or simply Bull), was only French by accident. The name Bull comes from Fredrik Rosing Bull who founded a company in Oslo in 1921 to sell a punched card sorting, recording, and adding machine (for accounting) he had patented two years earlier. The machine was instantly successful, as it broke the monopoly that IBM had leveraged on both terms (no sales, only leasing!) and prices. Fredrik Rosing Bull died in 1925 at only 37 years old, and the ownership of Bull was transferred to a consortium, who sold licenses to build and commercialize Bull machines in individual countries.

A Belgian businessman called Emile Genon bought licenses for most of Western Europe and then established his HQ in France (1931), a large market where manpower was relatively cheap, patents well-protected and data processing still lagging behind. After convoluted financial shenanigans, the new company became La Compagnie des Machines Bull in 1932, a company capitalistically unrelated to the Norwegian Bull, but that managed to poach the original Bull’s lead engineer: Knut Andreas Knutsen. Knutsen was a Tier S engineer, and designed machines that would turn Bull into an European leader of data processing equipment. The cash cows were the T30 (1931) and T50 (1934), tabulating printers that could print respectively 120 and 150 lines by minute, which must have been an oustanding number because apparently IBM never passed 80 lines by minute in the interwar period. Bull owned 15% of the French data processing market in 1939, and the Vichy years arrived… which were absolutely great for Bull, because IBM was de facto out of a market that expanded suddenly when the Vichy regime made the ID card compulsory.

After the liberation of France, Bull went through the épuration without issue (its stance during the war is still hotly debated among historians) and expanded everywhere: Europe, USA, South America, Japan and even the Soviet Union. As successful as it was, it was still however much behind its rival IBM. In 1948, IBM deployed is IBM 604 Electronic Calculating Punch – a machine that would take punched cards, execute a chain of operations on it (additions, subtractions, divisions, multiplications but also more specialized operations like payroll calculations) and then return more punched cards as a result. IBM sold thousands of those machines, and Bull understood that if they wanted to compete, they had to learn electronics.

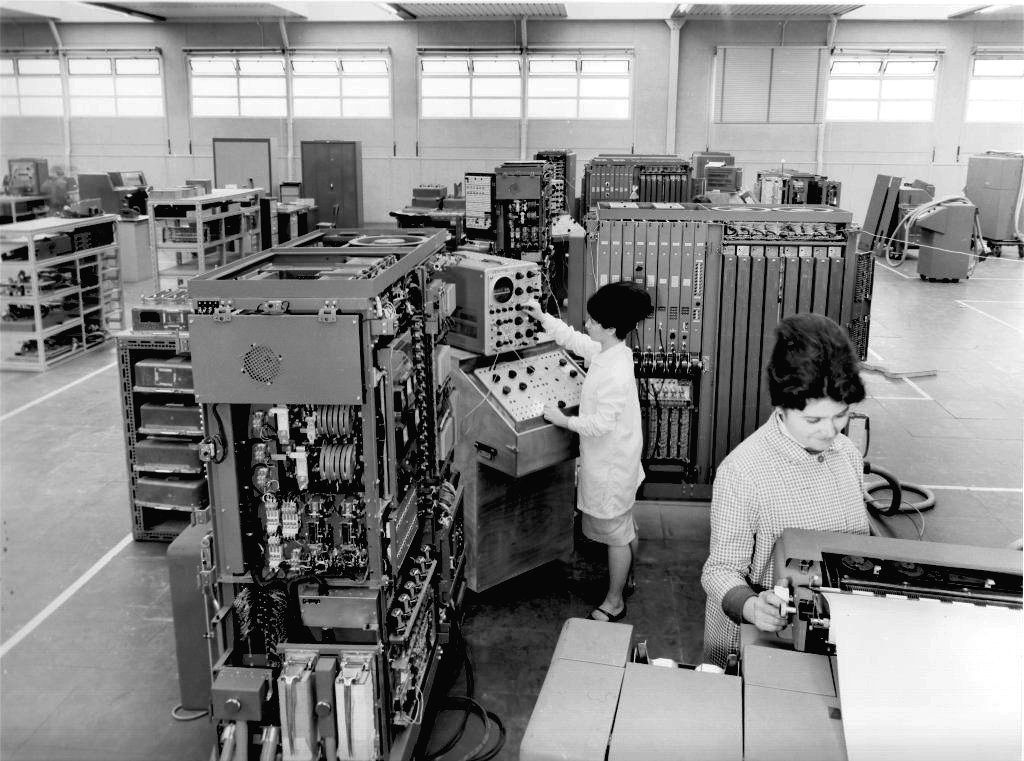

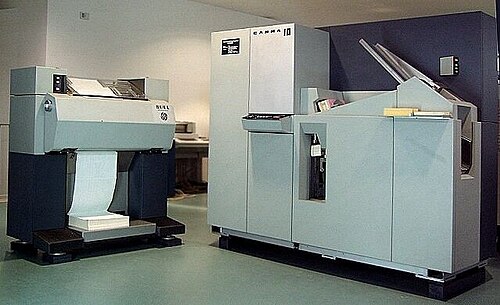

Bull went through a complete upheaval of its hiring, training and manufacturing process, but by 1952 they had their answer to the IBM 604 with the Gamma 3, an electronic calculating machine that would evolve, without planning for it, into the first full-fledged computer of Bull. The original worked as a peripheral to a tabulator, so it was not a full-fledged computer. Then Bull realized it could remove the tabulator and let the Gamma 3 be programmed by card: it was the Gamma 3 PPC but still not a full-fledged computer, because it lacked memory. Finally, in 1955, Bull added drum memory to the Gamma 3 PPC, and so the Gamma 3 ET was a full-fledged computer, and a commercially successful one at that. All models included, 1200 Gamma 3 were sold – a tremendous success for Bull, though most were probably not the ET version.

Yet, the Gamma 3 ET was not the first French computer – this feat had been achieved neither by a public laboratory nor an historical giant, but by what we would nowadays call a start-up: the SEA.

The Challenger: The Société d’Electronique et d’Automatisme

Where Bull made their first computers through unguided iterations, François-Henri Raymond had made his purpose from the moment he read the Von Neumann report. Shortly before the war, Raymond had worked for the Marine Nationale on the latest electronic technologies: radar, sonar, fire control. Demobilized after the defeat, his war years were uneventful. After the war he joined the leadership of the machine-tool maker GSP and became advisor for Sadir-Carpentier, a company that built electronic equipment (including the first French radar in 1939: the Barrage David); it is in this latter role that he was sent to the United States to find out what was state of the art – and that’s where he found and the Von Neumann report.

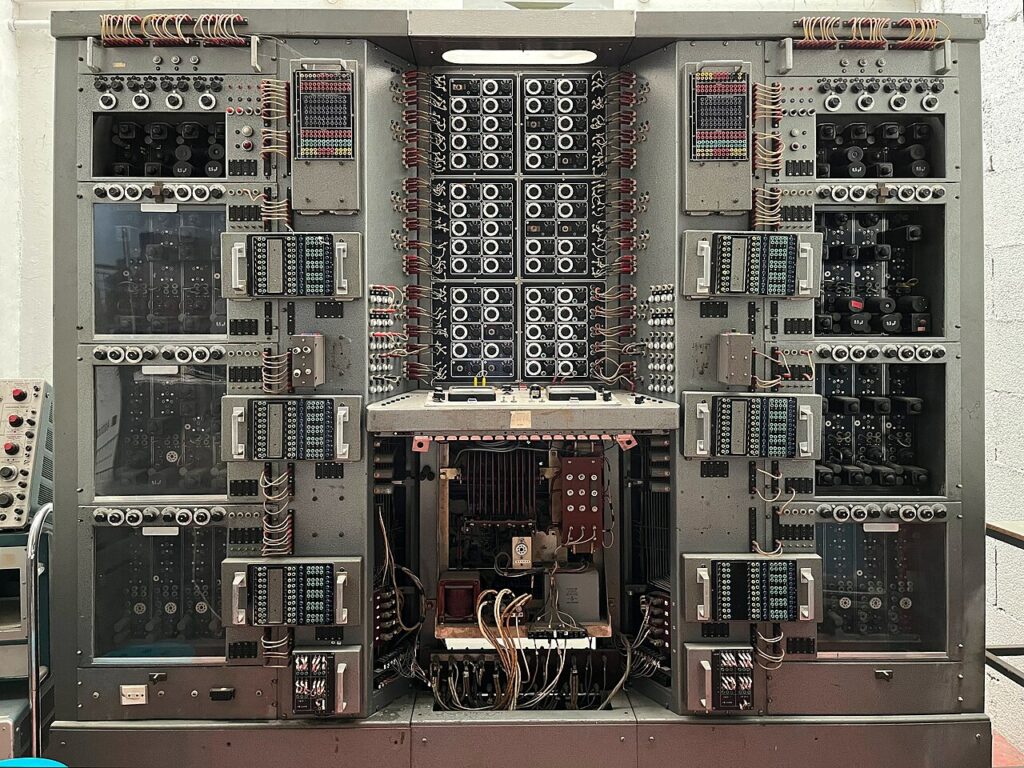

Returning to France, Raymond suggested to Sadir-Carpentier to build one of those computers. Sadir-Carpentier did not see the rationale for following the Americans in their collective pet projects. Fine then, Raymond would do it himself. However, when Raymond talked to his second employer GSP, they very much did see the point, so much so that not only did they promise to buy shares of the new society and join the board, but so did their own shareholders. With the capital secured, Raymond assembled a team of engineers (many of them friends and colleagues from his years in the Marine Nationale), founded the Société d’Electronique et d’Automatisme (SEA, 1947) and leveraged his contacts in the army, navy and air forces for his first contracts. The SEA first orders were analog computers, but of course Raymond was biding his time for an opportunity to build a full-fledged computer.

The SEA finally nailed such an opportunity in 1951, when French Army’s Laboratoire Central de l’Armement ordered a scientific computer – presumably they had lost patience with Couffignal. The SEA’s response was the CUBA (Calculateur Universel Binaire de l’Armement). The CUBA was state of the art when designed (Raymond was keeping tabs on the technological progresses in UK and US), but building it turned out to be harder than expected given that whatever new technology the Americans had started to use (magnetic core memory! transistors!) was not yet readily available in France. SEA had to import parts from UK and America, and even then the CUBA was delivered later than expected (1954 or 1955) and barely used – a mere footnote in history beyond “first French computer”. Meanwhile, the SEA had worked on two more universal computers: the CAB (Calculatrice Automatique Binaire) 1011 specialized in cryptographic works and in October 1955 the more universal CAB 2000 for the missile manufacturer Matra. 4 CAB 2000 would be eventually built.

The SEA’s defining computer however was the CAB 500, designed in the late 50s and delivered from 1961 onward. The CAB 500 was an attempt to build a “simple” computer that did not need highly specialized engineers to operate. Raymond made radical choices: the CAB 500 was shaped like a desk, could be plugged in a wall socket and did not need a dedicated room with air conditioning. It is sometimes described as the first desk computer: you could put it on your desk, sit down and use the typewriter to give commands to it. The SEA even embedded a specially designed language: the PAF [Programmation Automatique des Formules], which looks like BASIC but earlier and in French. The CAB 500 was the real breakthrough for SEA, with 100 machines sold, some as far as Japan, Soviet Union (2 machines) and China (1 machine).

L’Affaire Bull

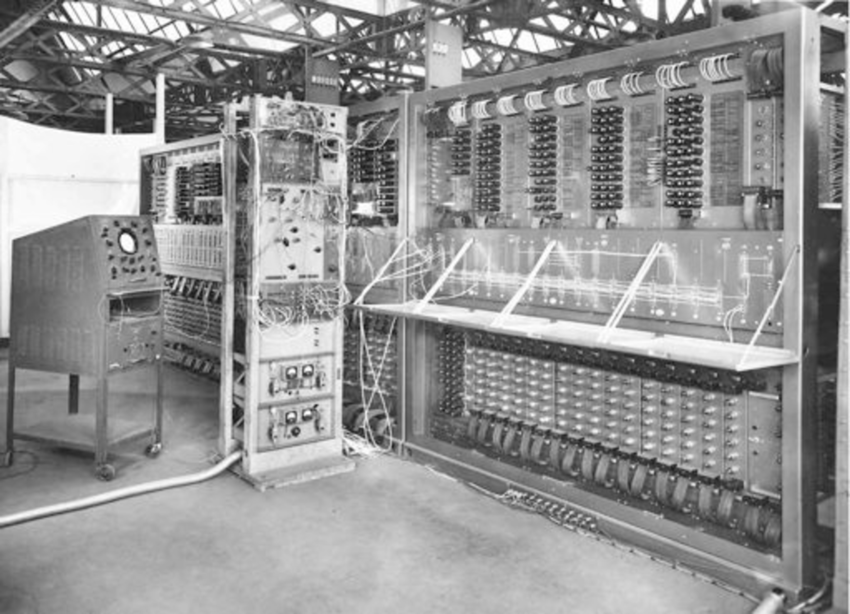

Bull had grown incredibly fast in the 50s on both its mechanic and its electronics activity, and by the end of the decade it was thanks to the Gamma 3 the second largest computer company in the world, though still much smaller than IBM. To feed its growth, Bull had launched massive investments in human resources, R&D, factories and of course computers, which it was leasing rather than selling. Bull was therefore running large debts, at least until the investments would pay-off. Unfortunately, they did not : in 1960 IBM released the IBM 1401, a rather small computer specifically designed as an answer to the Gamma 3. The computer was successful beyond IBM’s wildest expectations: it sold more than 10 000 in US alone. Meanwhile, Bull had bet on the incredibly massive and eye-wateringly expensive Gamma 60 – fewer than 20 customers ultimately bought or leased it. Starting in 1962, Bull was in crisis. While its revenue was stable or growing, it needed downsizing, a management reshuffle but more than anything it needed cash immediately. The French State, however, had its own idea about what Bull needed.

In July 1962, De Gaulle had finally ended the Algerian War, the drawn-out disaster that had brought him to power four years earlier. With his hands finally free, De Gaulle turned his attention to the question of the indépendance nationale. One of the cornerstones of this project was the nuclear bomb. Even though the first nuclear tests started in 1960, mastery of the weapon required powerful computers, and in early 1963 France ordered a Control Data 3600 for this purpose. The American government blocked the sales. This did not even slow down the French program – there were several similar computers already in France – but it showed De Gaulle and France could not be truly indépendant without controlling the computing. Just like that, Bull had become too strategic to fail for France.

This is how the Affaire Bull started. To face its debts, Bull prepared late 1963 to issue 100 millions Francs of bonds for foreign banks to subscribe. Foreign? The French government refused. Bull tried a French bank: the Crédit National, and the French government blocked it as well. What the French government really wanted was for Bull to be “saved” by creating a joint-venture with two larger French companies: the Compagnie Générale d’Electricité (CGE) and the Compagnie Générale de Télégraphie Sans Fil (CSF), both companies whose only computing activity was building computers under foreign licenses. Unfortunately for Bull, the three “partners” chosen by the French government had their own plan: not joint-venture, but full control. The CEO of the CGE bluntly told the CEO of Bull he was simply waiting for Bull to be bankrupt, the CSF and Paribas were more subtle but the vibe was the same.

As Bull was stuck between a rock and and a hard place, it received an unexpected proposal in September 1963. The giant General Electric (GE) was looking to enter the computing market, and offered Bull the opportunity to use its extensive commercial network. In exchange, GE would buy 20% of Bull’s capital through new shares emitted at the price of 200 Francs each. It was a win-win situation, an offer Bull could not refuse. Alas, the government could, and after a long delay it officially rejected it in the first days February 1964. One week later, the French government sent its own “proposal”, negotiated without Bull: in short, financial support from the French government and Paris in exchange of Paribas, the CSF and the CGE taking control of the company, among other through a raise of capital at the price of 50 Francs by share. Bull’s remaining cash had totally dried up at that point and the CEO of Bull folded. His signature, however, had to be confirmed in a shareholder’s meeting to be held on the 14th of April, 1964

This left some time. Some key-shareholders and stakeholders of Bull were not quite happy with this agreement, if only because GE had proposed 200 Francs by share and the consortium proposed 50 Francs, and so they resumed discussion with GE. A new proposal was drafted which would leave Bull in control (at 51%) of its industrial/production part but hand the commercial activity to GE (at 51%). This last minute agreement was finished on the 10th of April, shown to the ministry of Finance which… agreed, probably because GE used the opportunity to explain that if they did not have Bull they would get its Italian and German equivalents Olivetti, Siemens and Telefunken, so Bull would have to compete against that, too. Four days later, the shareholders approved the agreement. Two weeks later, in early May 1964, the French government changed its mind and said that the agreement had to be renegotiated.

Of course, the French government could not cancel the agreement, and GE – at that point well-aware of the dire situation Bull was in – and had huge leverage. The final agreement was worse than what the government had just asked to negotiate. GE demanded control of not only the commercial entity but also of the industrial one, and at a discount: they had proposed 200 Francs by share a few months before? Now it would be 75 Francs by share; after all the other options had only proposed 50 Francs! One of the French most strategic assets had just been handed over to a foreign company. Oh well, there was another French company good with computers.

Not according to Plan

In September 1966, the French government launched the Plan Calcul. It is an all-around push that goes way beyond “building computers”: training, education, components, peripherals. In some areas it worked, in others – not at all, and computers were in the second category. It started with the sacrifice of what was left of the French-owned computing industry: the SEA (now owned by Schneider) was forced into a joint-venture with the “foreign computers” branches of the CSF (now owned by Thomson) and the CGE, thus forming the Compagnie Internationale pour l’Informatique (CII), The French government’s plan was to turn the CII into a national champion of computing; at first the French State would subsidize it of course, but after a couple of years the national champion would be able to fly of its own and presumably become an international leader – hence the name.

Once again, the government assumed that the companies it was working with were aligned with the plan. Thomson and the CGE were bigger and wielded infinitely more political clout than either Schneider and the SEA, and so of course they took effective control of the CII – the SEA simply disappeared both in paper and in spirit. The French government had promised to only equip itself with computers from the CII, and the CGE-controlled CII was very happy to address the captive French public market… by importing and “adapting” American computers from its historic partner Scientific Data System. Eventually, the CII produced its first really French computer (with foreign parts nonetheless) in 1969: the Iris 50 and soon after that the Iris 80. While those Iris were excellent computers, their protected market (the French administration and the French public research labs) was tiny; everywhere else it was competing frontally against IBM which was cheaper and had a huge installed base. The CII kept operating at a loss, with financial support it required from the government growing every year instead of shrinking – massive investment was thrown into the “national champion” with no end in sight. The CII shareholders largely profited from this support, and barely contributed to the pot.

Eventually, the CII saw a solution. Given its small size and its lack of commercial branch, it decided to team up in 1972 with two much larger companies: Siemens (Germany) and Phillips (Netherlands) to form another joint-venture: UNIDATA, a company that was poised to become the European answer to IBM. But once again, industrial concentration without a real plan does not pay-off: the three companies didn’t work well together and the CII required even more subsidies from the French State to weigh in front of its “partners”. In 1974, the newly elected President Giscard d’Estaing decided to cut the Gordian knot by simply ending the Plan Calcul. Billions of Francs had been squandered into the CII, for almost no result.

This ends my long yet heavily abridged history of French mainframe computing. However, another event will become much more relevant to our interest: in January 1973 the French company R2E showcased the Micral N, the “first personal computer using a microprocessor“. Personal computing is coming.

Gaming on French mainframe.

To conclude this admittedly long story, let’s finally talk about games. While retro-bloggers have discussed at length American mainframe games, it is almost impossible to find anything about French mainframe games. A few years ago, I asked my own father what he played at the Ecole Centrale de Lille in the mid-70s, and in his recollection there was only one game available: Lunar Lander. Video game historians Alexis Blanchet and Guillaume Montagnon asked themselves “whether there was the French equivalent of a Spacewar! or of a Hamurabi”, or really any French mainframe game. For the reasons we covered, there were way fewer computers per capita in France than in USA in that era, and so computing time was too precious to be spent on games. There was a question of culture – France in the 70s was a status society, and above a certain social class it was simply unseemly to play games. Nonetheless, after interviewing survivors of the era and deep-diving in archives, Blanchet and Montagnon found a few of them.

The French video games were used more for testing, training and demonstration than for playing. The first one Blanchet and Montagnon could track was a port of Go Bang (a variation of Go that can be played quickly), coded in 1960 by Paul Braffort on Euratom’s IBM 1620 and IBM 790 – Braffort wanted to test “non-numerical” problem resolution by computer. Braffort did not continue making games, but Go Bang proved popular in France because we find it (or a variant thereof) in the second (?) video capture of a French computer game in 1968 (model unknown). The game irradiates Frenchness, with random non-sensical comments during the game (including barks!) and a closing poem to “reward” the player for their victory.

Blanchet & Montagnon tracked a few more games, including an unnamed aiming game (1966) with a light-pen on PDP-8, which had to be retired because players would hit the very expensive screen with the light-pen. What’s sure is that unlike the American scene, none of the French games “travelled”, even within France. They were there to demonstrate the capabilities of specific computers, but there weren’t any French equivalents of MERITSS, PLATO or a student plugging remotely to the Lawrence Hall of Science. By the 70s, American games started seeping in, first slowly, then faster as games could just be copied from magazines like Byte. There were a handful of French games of course, but small in scope and in interest; French gaming would start for real on PC.

Main Sources

- BULL 70 ans de traitement de l’information, Pierre-Eric Mounier-Kuhn, 1990, the best sum-up I found on the history of Bull

- L’informatique malade de l’Etat, Jean-Pierre Brulé. 1995

- Une aventure qui se termine mal : le SEA, François Henri Raymond, 1988 – a recollection from the founder of SEA

- Du radar naval à l’informatique : François-Henri Raymond (1914-2000), Pierre-Eric Mounier-Kuhn, 2020

- Le Plan Calcul, Bull et l’Industrie des Composants, les contradictions d’une stratégie., Pierre-Eric Mounier-Kuhn, 1994

- Le Plan Calcul, François-Henri Raymond, 1988

- L’Affaire Bull, Georges Vieillard, 1969

- Origins of Architecture and Design of the IBM 1401: Various documents on the IBM 1401, including emails from IBM staffers about how the 1401 was an answer to Bull.

- Une histoire du jeu vidéo en France, Alexis Blanchet and Guillaume Montagnon, 2020

- C’était de Gaulle, Alain Peyrefitte, 2000. It is the source of the quotation. I am not 100% sure Alain Peyrefitte was a reliable narrator, but it’s certainly something De Gaulle could have said.

9 Comments

Hi, could you give me some details on this comment?

“Colossal Cave Adventure seems to have received an early translation”

I’ve recently made a discovery related to this that you might find interesting, but I’d like to hear what you know first, to avoid duplication.

Quoting l’Histoire du Jeu Vidéo en France.:

“Certains chercheurs découvrent par ailleurs les jeux informatiques américains en partant faire carrière à l’étranger, comme Olivier Lecarme qui pratique ainsi Colossal Cave Adventure (1976-1977) au Canada: « J’ai joué à ce jeu à l’université de Montréal […] Le programme avait été traduit en français, Québec oblige.»”

So this translation was from Québec, which I should have specified. Lecarme returned to France in 1974, so it’s was somewhere between 1970 and 1974, before the “official French translation” in 1979. Reading again, I may have misunderstood and there is no indication that this version arrived in France – I will remove this specific sentence, and remove it. On the other hand, it’s sure that Adventure impressed the French as it is mentioned by a different researcher, Patrick Greussay, who discovered it either at the Rochester University or at the MIT, along with Rogue, which he translated around 1980.

Well, it couldn’t have been ’70-’74, as the original hadn’t been written yet, but I found a bio of Lecarme from the university, and he was back there twice, first for two weeks in July of ’77, and then again from July to December of ’78, so it must have been during that last stint that he encountered the French translation, which makes sense chronologically. In any case, that’s new information, and I’ll need to look into it more, so thanks for the reference.

Funnily enough, I’ve been working on a history/preservation project with a different university involving some early Canadian games, and Bull features prominently in it. Unfortunately it’s not in a good way, as their continued commercial involvement with certain archaic mainframe operating systems has made it impossible to run the games in a simulator…

Anyway, as I mentioned before, here’s some related information that you might find interesting:

I recently discovered a unique French translation of Adventure/Colossal Cave for VAX/VMS from 1985, which was hidden deep in an old file archive. It was programmed in France and distributed through the French branch of DECUS, eventually making its way through tape swaps to a distribution set from San Francisco, where it’s been lying undisturbed ever since. It’s going to be a bit of a rigamarole to get it up and running, but I have the files and it should be possible. Anyway, it’s the only French-made mainframe/minicomputer game that I’ve ever encountered “in the wild”, and it seems entirely unknown otherwise. The earlier “Bilingual Adventure” version for home computers was actually programmed in New Jersey and never sold commercialy in France as far as I know, so there’s some historical interest here, at the very least.

Excellent read. Industrial history, particularly when it deals with failures, is fascinating. In short, the French government repeatedly f***ed its own internal development through mismanagement, bullying and expensive-yet-useless public funding.

How very Mediterranean of you.

I hope we’ll get a Italy article sooner or later. I know Olivetti by fame, but by the time I was alive they were merely a name and a shell of disastrous 90ies failures.

> mismanagement, bullying and expensive-yet-useless public funding

Every state is more or less like that. The advantage of USA and China (in the past, Soviet Union and British Empire) is that they have so much population and money that they have access to a bigger pool of scientific and entrepreneurial talent, and that they have the time to retry failed attempts as there is not much competition at their level. France could have eventually succeeded, had the United States not eaten their lunch so promptly.

One could argue that France’s big-government approach failed against U.S. capitalistic meritocracy, but in the same years the space race showed that some technological breakthroughs could only be attained with a strong state-coordinated project, so I wouldn’t blame Paris for organising things that way.

I reckon that the big successes of French public planning were companies whose ultimate customer was the State itself or public companies it controlled: energy/nuclear, weapons, transportation.

Also, in USA, the US State cannot force a firm to do its bidding. In France, it can, thanks to the size of public sector/market and because (due to the former) it can give orders to banks (if France really wants Société Générale or Paribas to do something, the SG and Paribas will do it, else they’re out of the big tickets public projects). It creates two really poor consequence: the first one is that it makes the State sloppy (instead of working with subtle incitations, it just gives orders), the second is that the French State can be weaponized by large companies with political clout. “Hey, this small company is very successful, wouldn’t it better for France if it was part of a large group like us“. I gave the example of Bull and the SEA, but it happened again and again. Telematique does mini-computers that are better than the CII’s? The State forces it to merge in 1976. R2E does successful micro-computers? Well, in 1980 the State imagines that surely CII (at this point the CII-Honeywell-Bull, it’s complicated) should have it… At least, Italy was protected from that by its regionalism.

Early Italian computing (Olivetti in particular) is really interesting. It’s really a case of successful Private <> State [well, “Region” because this is Italy] parternship.

There are other fun stuff – I have even prepared a meme

I’m incredibly curious about that article, because I’ve never read much about Italian tech industry. I’m also quite curious about the “regionalism”, because I believed the peculiar and haphazard regionalization of Italian politics/insutry was more recent (or relatively recent, post late 70ies-mid 80ies with it going full speed in the 2000ies).

Also that meme is flat-out hilarious

I’m looking forward for the article about Italy! But, as Italian and proud spectrumista, I’m immensely offended by the meme 😅