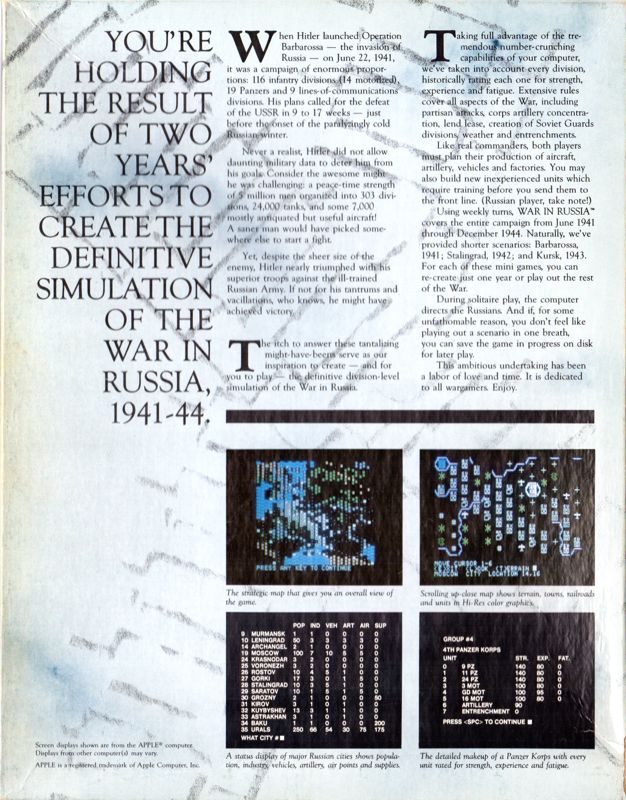

After four games covering naval campaigns, Gary Grigsby moved to the other theme that would define his career as a designer: the Eastern Front. According to my database, by the time War in Russia was released in June 1984 there had been exactly 50 computer wargames on WW2, but only two covered the entirety of Russia (Panzers East! and Chris Crawford’s Eastern Front 1941), and of those two none covered more than one year of war. Crawford pondered covering the entirety of the Eastern Front in his game, but he soon found it better to focus only on the first year. Later, Crawford added a 1942 scenario, but as an independent module to the 1941 and his code never supported the transition from winter to spring.

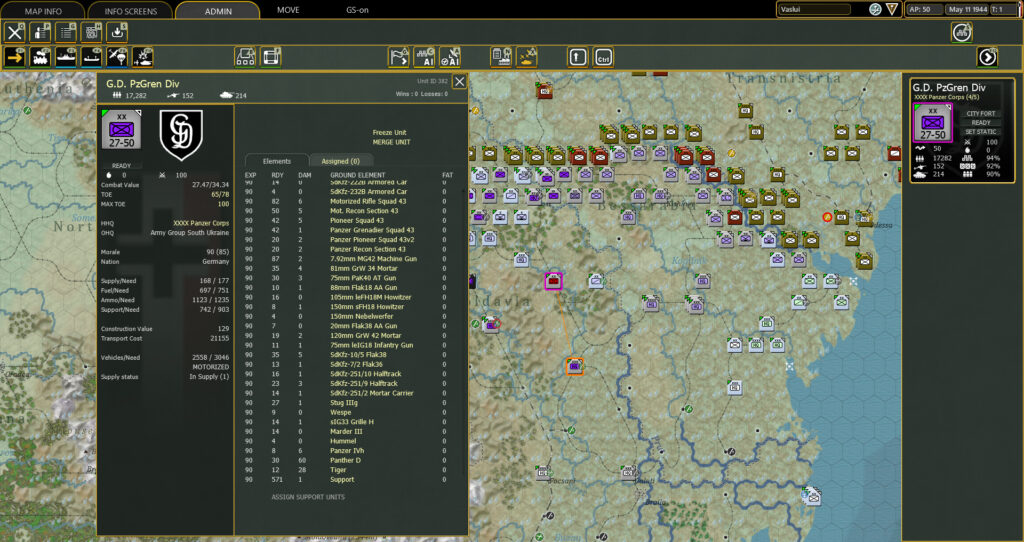

In addition to covering a longer timeframe than its closest competitors, War in Russia digs deeper: Eastern Front 1941 was played at the Corps level, whereas War in Russia tracks units down to the division level. I estimate that on a modern computer with fast emulation, a campaign may last anywhere between 8 (early finish) and 25 hours (for a 1941-1945 playthrough). This is the same order of magnitude as the time it takes to play the latest Hearts of Iron – and that’s before taking into account the speed of 1984 computers. War in Russia may have well been the real first monster wargame on computer.

The development of War in Russia started in the summer of 1983, still in BASIC, and according to Joel Billings the game was “working at the basic level” in September 1983. The balancing values were still placeholders, as Grigsby remembers having done most of the historical research later in October 1983, during a trip to the Grand Canyon. The game was therefore ready in late 1983, and started its final QA and balancing pass while Grigsby as usual started working on the next project – Objective Kursk.

When we think “QA” nowadays, we imagine a dedicated team with cheat code, logs and other QA tools. But of course, in 1984 “QA” in SSI meant “Joel Billings, Paul Murray and a bunch of friends playing the game as normal people“. All those people had jobs, and as I said War in Russia is long. In March 1984, the team found a critical bug in the combat formula – a bug so bad that all the tests on the balancing had to be thrown out, and the iterations restarted from scratch. Objective Kursk meanwhile had also reached the testing/balancing phase – it was after all using the same engine as War in Russia – and because it had a much smaller scope its QA and balancing was much shorter! Objective Kursk, started 6 months after War in Russia, ended up being released one month before the latter in May 1984 – though Billings ponders whether it may have been held an extra bit to let Murray finish the Atari (Assembler) port of the game – not the initial plan but given the game was already late there were benefits to releasing the two versions together.

Despite the scope of War in Russia and the time it took to develop it, it is obvious that Grigsby had hoped to add more and for one reason or another (balancing? lack of time? memory size?) some content was removed. This is particularly obvious in two features: supplies and division types.

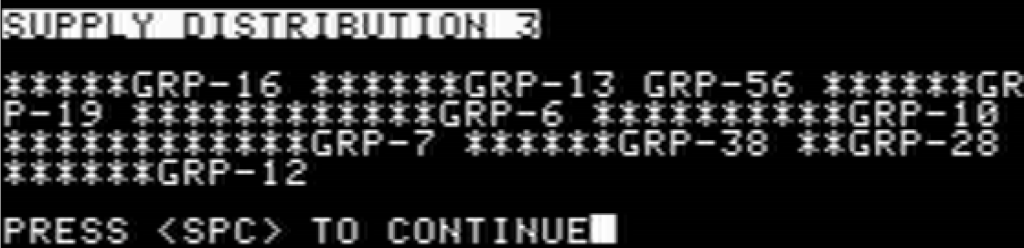

Let’s first talk about supplies. It is remarkably simple: at the beginning of each turn the player has a number of “depot units” they can move through railroads and open terrain and which can once each supply all units within two squares of them. Yet, if you read the manual, this is much more complicated: each division whose fatigue is not 0 consumes “supply points” (1 for infantry, 2 for non-infantry ) and if there are no more supply points then supply time is over. This does not seem to have been implemented however, or rather it seems to have been implemented and then balanced out of the game. The Axis generates 225 supply points, for a cap of 199 divisions and not more than say 40 non-infantry divisions (I ended the game with 34) so the maximum supply you could ever possibly need is around 240. Obviously, I never reached that cap and rarely needed half that much: my units were often too spread to be all supplied, and a good chunk of my infantry was holding position and not fatigued. As for the Soviets, they generate 425 supply points every turn and of course they won’t be needing all that either.

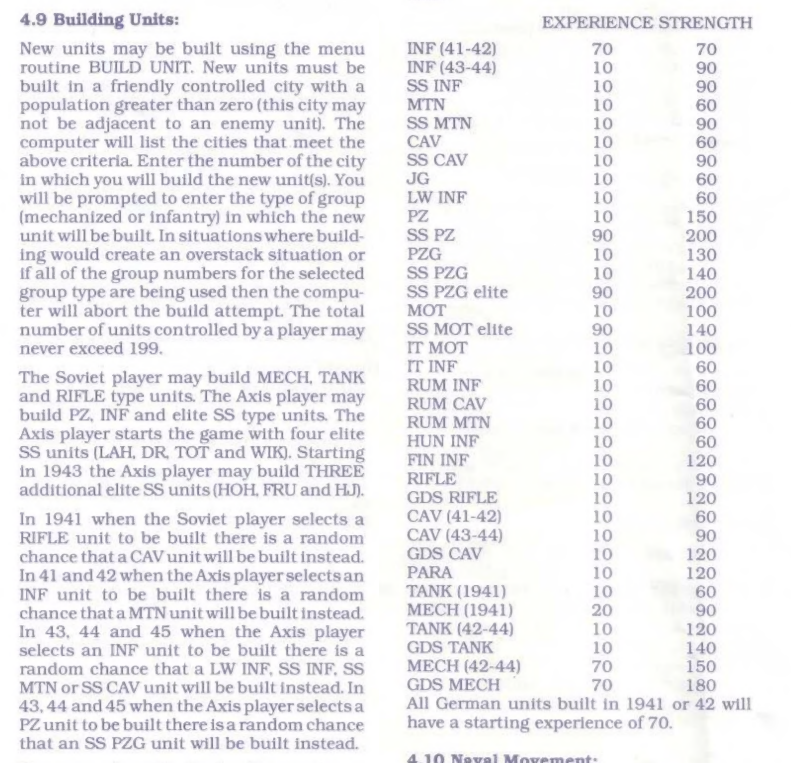

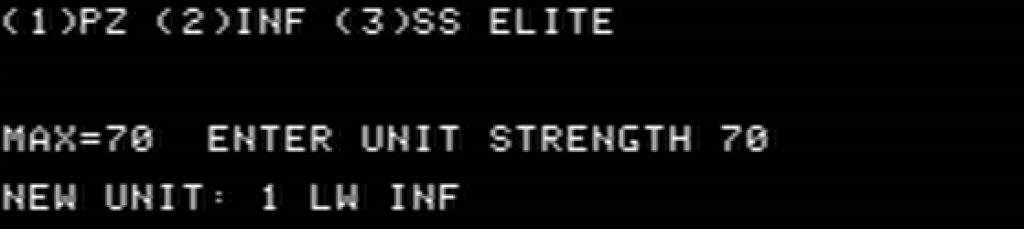

The supply system may have been effectively cut, but for my second topic – the division types – it is obvious that Grigsby could not go as far as he planned. War in Russia includes 35 division types. Some are “foreign” (Finnish, Romanian, Slovakian, etc…) but most are variants of Soviet and German units (eg Mountain Infantry vs Regular Infantry). The player does not choose which variants they build, instead they pick the general category (“infantry”, “mechanized”) and the game automatically determines whether the player receives a rifle division or an inferior cavalry division, a panzer division or an inferior motorized division… Those “inferior” divisions have no advantage over their normal counterparts, they’re just worse and in some cases will remain so until the end of the game.

As the game progresses, most divisions upgrade to another (eg Motorized Divisions are converted to PanzerGrenadiers [PZG]), but the German mountain divisions will remain stuck in 1941.

Each type of division has its own “upgrade” rule, but otherwise their behaviour on the field is fully dependent on their type (with two exceptions: Finns refuse naval transports and the Italian Motorized division behaves like an infantry division). I suspect that Grigsby wanted to give more specific rules to specific divisions – maybe make cavalry more mobile than infantry, mountain divisions fight or move better in difficult terrain – else it was a lot of effort just to frustrate the player. In any case, Objective Kursk would certainly go down to the level of the division – and even to the individual vehicles – for combat resolution, so clearly the idea was floating in Grigsby head.

The Luftwaffe divisions being a waste of perfectly good division slots is realistic and I liked that.

In any case, SSI knew it had something different with War in Russia and sold it at the new high price point of $79.95 (no game had passed $59.95 before that), and still at that price you did not get any goodies in the box: only the game, a manual and a map – the real value was in the disk.

1942 – Case Blue

I had a high opinion of my 1941 scenario, but it is generally easy to make Barbarossa scenarios fun: the player keeps winning and advancing and as the designer you can even have the carrot that if the player advances fast enough they may end the game here and there. That’s why I wanted to try the 1942 scenario: Case Blue. I also tested a higher level of difficulty.

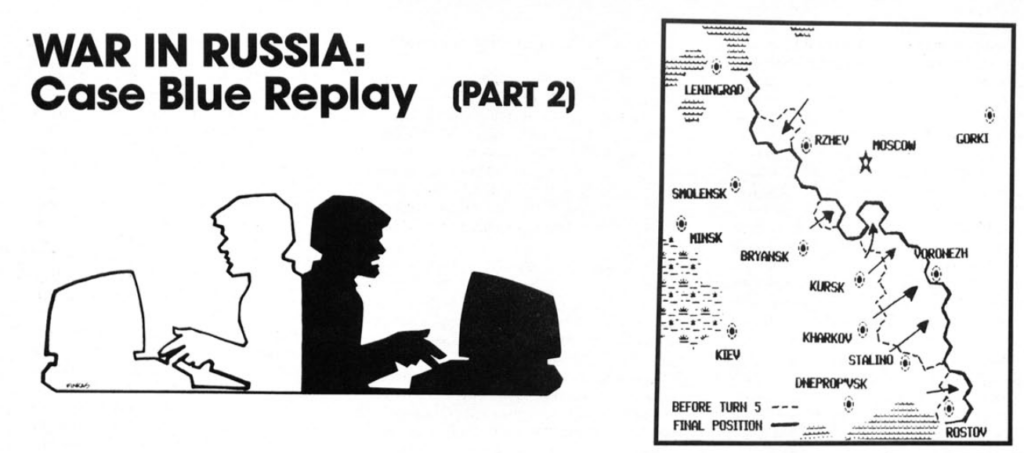

The map started with a frontline spanning from Leningrad (encircled) to Rostov. The Soviets have significant mechanized reserves behind the front, the Axis have not.

The scenario follows the historical deployment so naturally I expected the Soviets to be weaker in the South. I spend several turns transferring all my motorized and Panzer divisions South to Eastern Ukraine, then attack. As expected, the Soviet units were smallish, sometimes 2-divisions only, and I breached easily. In August 1943, I reached Stalingrad. So far, historical.

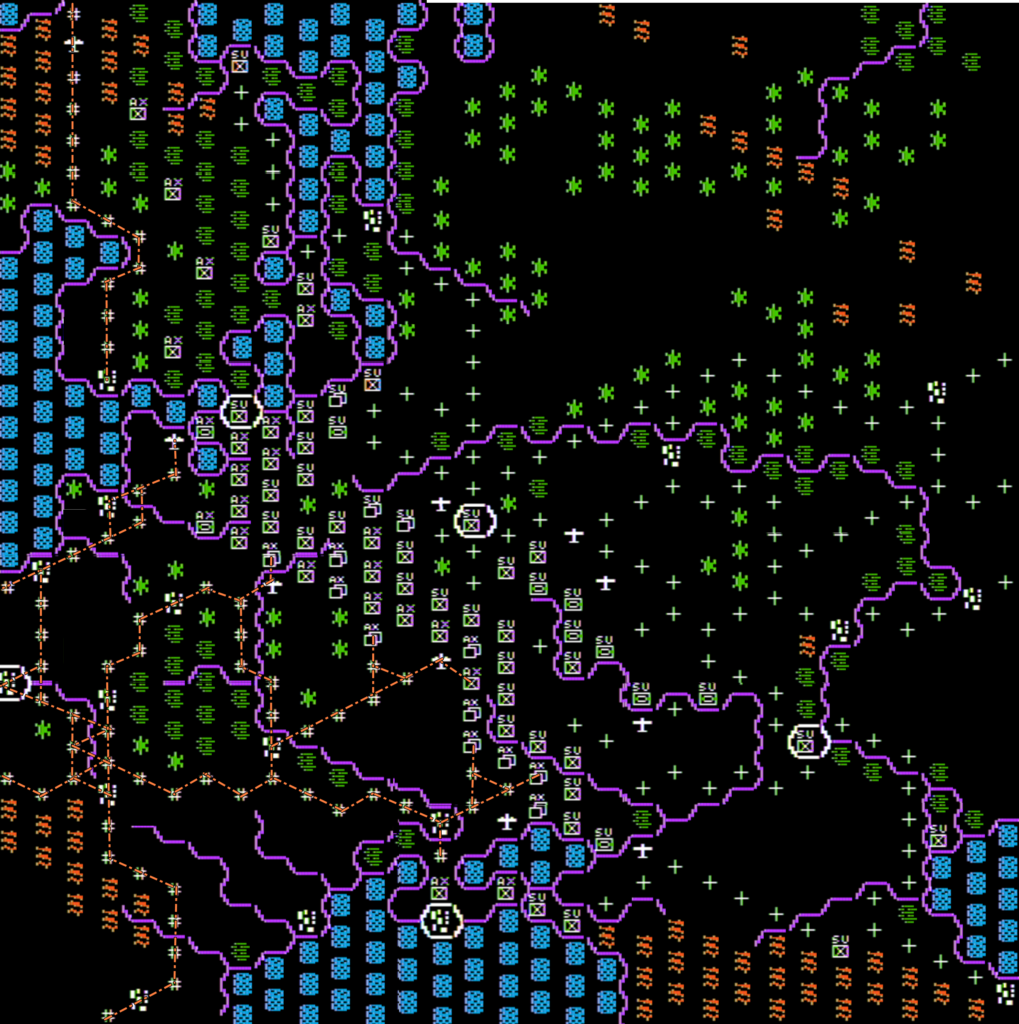

Instead of assaulting Stalingrad – I have seen the movie, I knew how it ends – I pivoted North. My objective was to isolate the Soviet units on the frontline from their supplies coming from the East. As soon as possible, I sent lone motorized divisions to cut the Soviet railroads. Sometimes, the Soviets chased them, more often they did not. By October 1943, only two supply depots, coming from Archangelsk, reached the Soviet frontline every turn. The units I sent forward were weak, but I was building a rail lifeline. The Soviets did not really try to escape from the encirclement, all they did was mobilize new mechanized divisions and attack my breakthrough from the East.

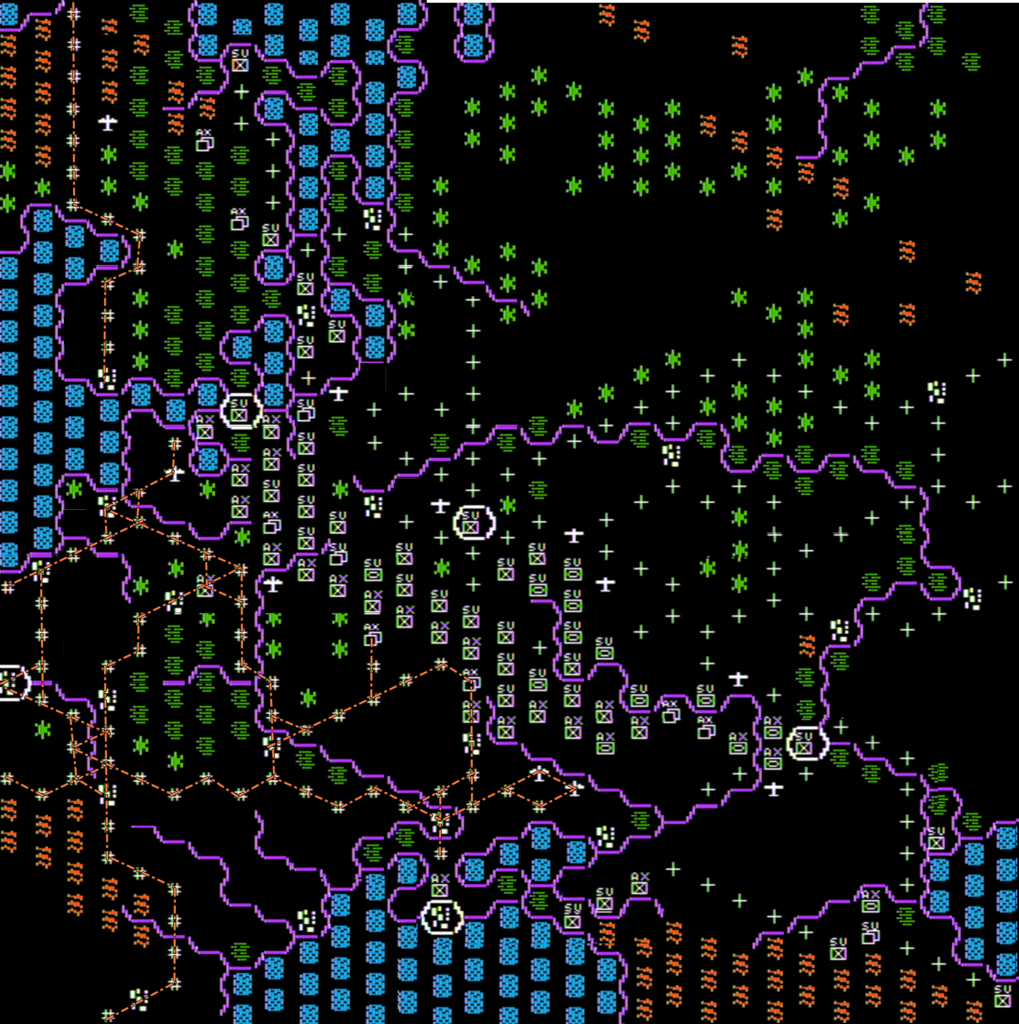

This battle lasted for most of winter, with the Soviets occasionally reaching my railroad and stopping me from building further (particularly when I am under the Very Cold handicap). Still, I eventually prevailed: all my Panzer Corps were allocated to this battle whereas the Soviets had stopped bringing reinforcements for reasons I don’t understand: as I checked later, they still had the reserve to build units. Possibly the computer earmarked those reserves to reinforce existing units, but of course could not reinforce any as I had isolated so many of them.

By the end of winter in March my trains could ride as far as Gorki, East-North-East of Moscow. The last supply lifelines of the latter was cut and it was then totally isolated, along with all the Soviet units in the middle of the map.

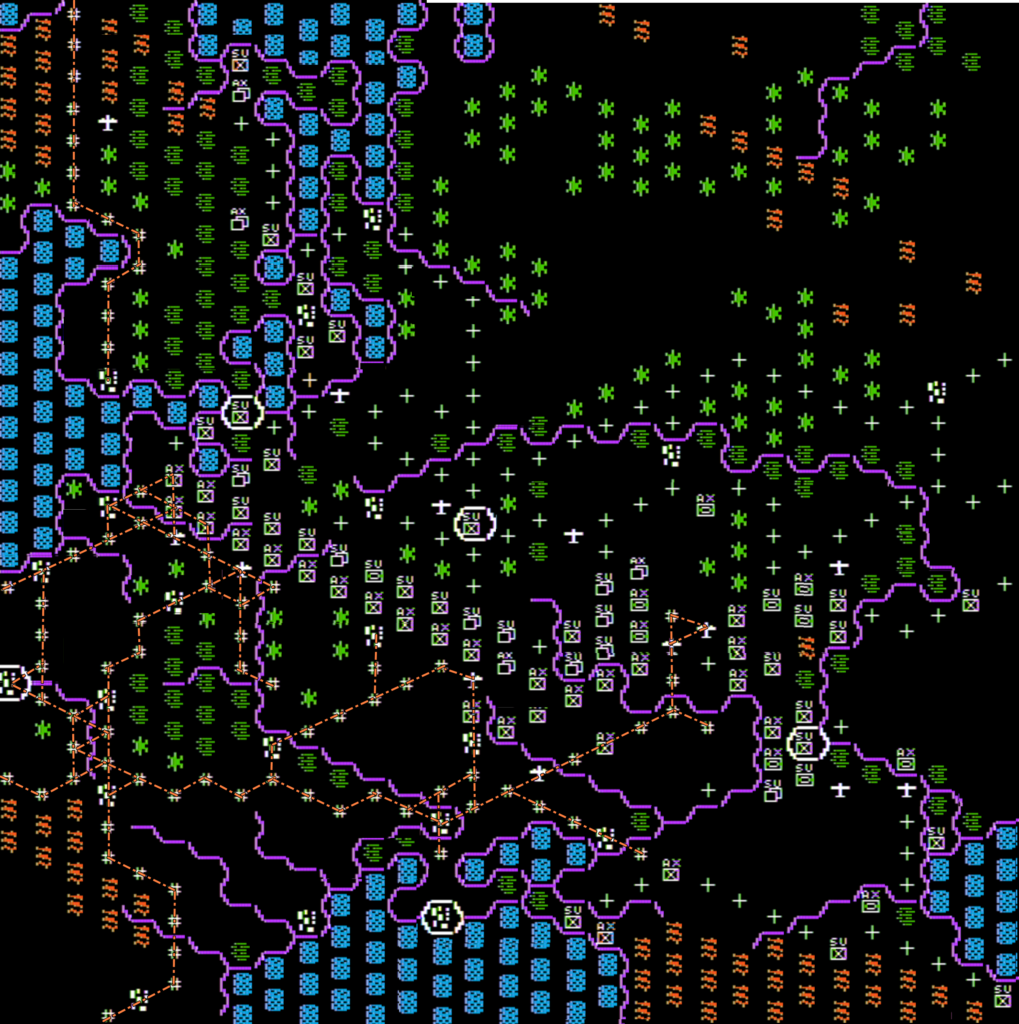

The game was effectively won. The last dynamic action took place between Saratov and Kubyshev where I overwhelmed, surrounded and destroyed the remaining Soviet mechanized divisions. Everywhere else, I just had to attack enough: I could resupply and reinforce and they could not. I eventually won the game on October 1943, 67 turns after starting the campaign.

This was again fun, though not quite as much as the Barbarossa scenario – possibly because I knew how to trick the AI. I won’t be doing the 1943 scenario: the Kursk campaign is my least favourite and Objective Kursk is coming soon anyway. Let’s move to the ratings!

Ratings & Reviews

War in Russia by Gary Grigsby, published by SSI, USA

First release: June 1984 on Atari and Apple II

Genre: Land operations

Average duration of a campaign : 5-10 minutes by turn, almost 200 turns for the longest campaign.

Total time played : 25-30 hours

AAR: Part 1, Part 2

Complexity: High (3/5)

Final Rating: Three stars

Ranking at the time of review: 2/131

A. Presentation

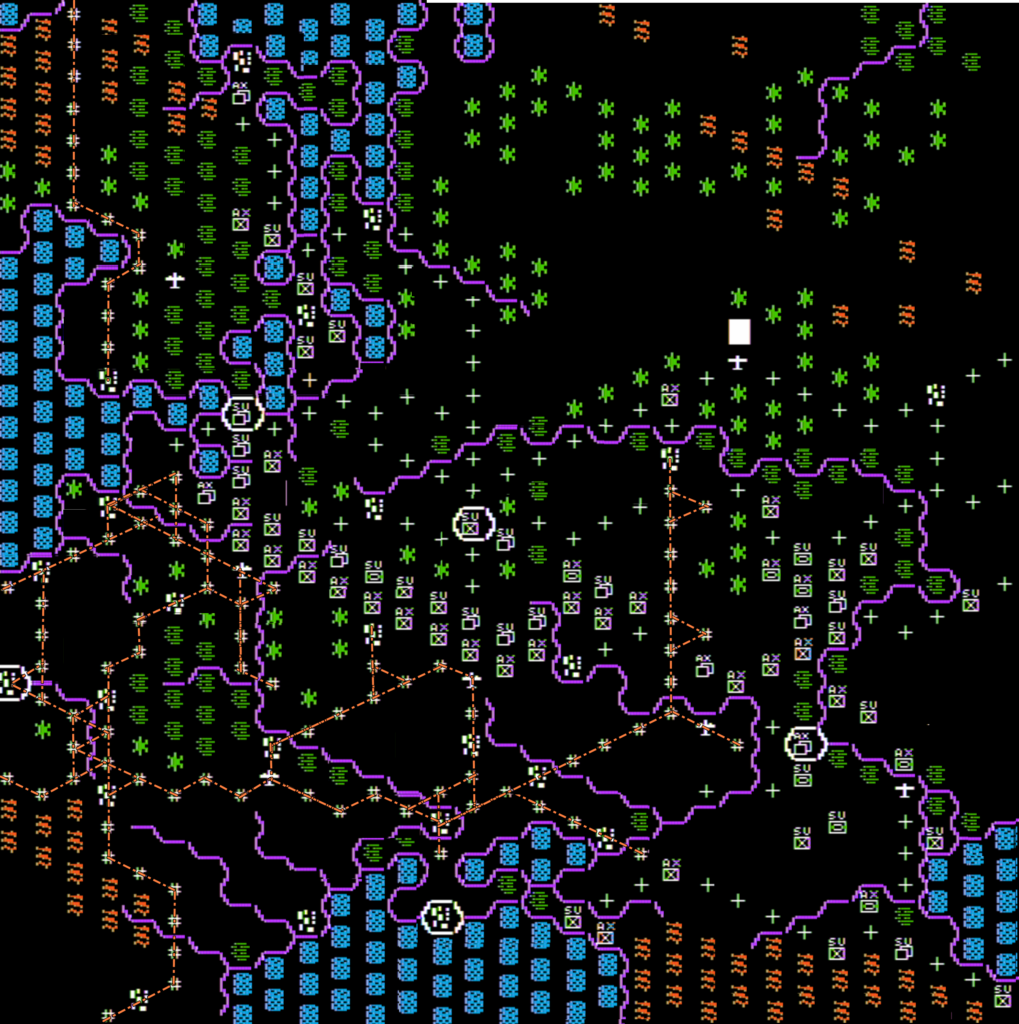

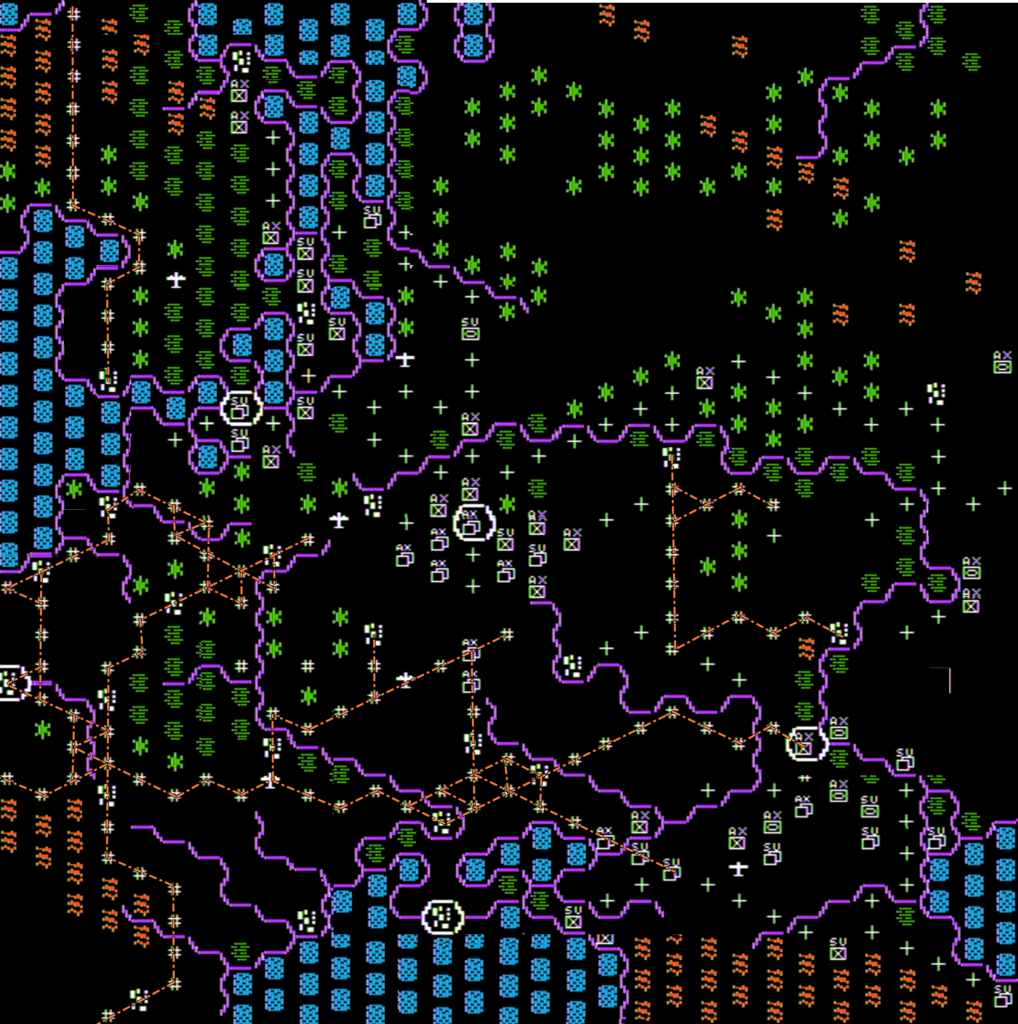

Adequate. Not much to say here. If someone had told me to imagine a “strategy game from the early 80s“, I would have envisioned exactly War in Russia. Nothing stands out, but it does the job.

B. UI, Clarity of rules and outcomes

Acceptable. War in Russia has the typical issues of SSI games: you will need to check the manual regularly as key rules are not repeated in the game, and said manual is not as clear as it could be (information pertaining to the same copy can be distributed in different parts). The game also obfuscates some important information: you cannot check your units’ supply level when distributing supplies, you cannot see the fortification level of units you’ve just attacked.

It is also easy to make a mistake that costs you. To take the worst example: the game splits movement between tactical and strategical. Tactical orders are given through a dedicated command menu, whereas strategical commands are given “by default” from the root unit menu and override the tactical commands – so guess what kept happening after I gave tactical orders and wanted to move to the next unit.

Still, War in Russia is really playable for a game of its complexity. I appreciate some efforts to automatize supplies (you can order them to go to the last place you sent them last turn). That’s not a lot, but I don’t remember any other game doing that.

C. Systems

Quite good. The game has a lot of features, not all of them work well and some are pointless (eg you can choose where to build your industry, but there is no reason not to build them directly in Germany), but the game works and given the number of moving pieces, the hundreds of divisions, the size of the map, that’s impressive.

I feel I’ve already explained how the game works during the AARs, so I will only focus on two items that stand out:

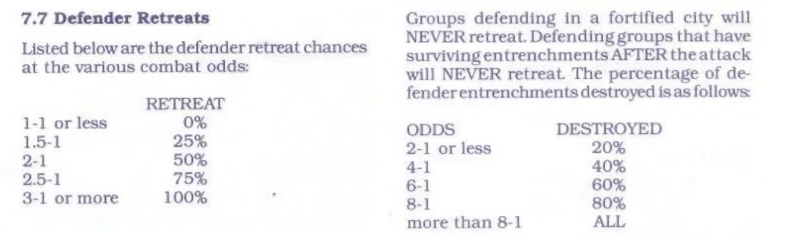

First, the tactical part works due to the fortification rule. Each unit has 50% to fortify every turn, adding 20% to its defence at every level of fortification (maximum: 5), levels of fortification they can lose when attacked. More importantly, units that are still fortified cannot retreat, whereas units without fortification are easy to push back (a 1.5:1 ratio can be enough, which is easy to muster as attacks can be done from several hexagons and defence from only one). This means that if you put in the effort, you can push almost any unit from any location in a few turns – and so can the Soviets when Winter comes. It keeps you on your toes, makes the game dynamic and gives you theoretically a real choice on your strategy.

Of course, pushing one unit away is not going to help you much, because you need to create a passage 3-hexagons wide to have your railroad. And that brings me to the second thing I want to mention: : BOY DID I LIKE BUILDING MY RAILROADS. Every turn I laid out that new piece of railroad, I had new tactical options, new degrees of freedom. All my strategy, all my tactics became about pushing the railroad forward. I had a moment of elation every time I could chase the Soviet occupying the piece of land on which I wanted my train to pass. The railroad really tied the game together.

D. Scenario design & balancing

Quite good. The game comes with 3 scenarios with short/long variation which is generous for the era. Additionally, increasing difficulty triggers ruleset changes rather than simply more/stronger Soviets, which I appreciate – and even then the additional Soviets are not created from thin air but are extra Siberian divisions coming to defend the Motherland.

On the other hand, the AI is weak: it barely attacks except in cold/very cold weather (that’s one of the things I wanted to check by playing the 1942 scenario until 1943) and for a game so focused on supply lines it manages them horribly: it pushes its supply depots as far as possible (even if it means not supplying units on the way), always using the same routes (making them trivial to block) and it barely reacts when its roads are cut. That’s a bummer, but given you still need to pierce the front before falling on the Soviet supply lines, there is still an interesting challenge for dozens of turns.

E. Did I make interesting decisions?

Yes, both tactical (including on where exactly I should put my new piece of railroad) and strategic – at least for the first half of each campaign. The second half was both times mostly about grinding unsupplied units.

F. Final Rating

Three stars. War in Russia is impressive for its era and still pleasant to play nowadays, if you can stomach the UI and unclear manual. While not as well-designed and tight as Eastern Front 1941, I found it more fun as it created more interesting tactical situations, and because of course you don’t build railroads in Eastern Front 1941. However, the number of minor issues and the weakness of its AI keeps it one category below Reach for the Stars, for now the only game to which I gave four stars.

Reception

War in Russia received few reviews – I suppose few were willing to test a game of that price and size – but the few reviews it received were lavish. Russel Sipe for instance reckoned in the December 1984 issue of Games: “Without a doubt. War in Russia is the most significant computer wargame release this year.“, and Bob Curtin states in the July issue of Analog Computing: “SSI is the premier house for computer war games, and War in Russia is one of the best in the house.” I found the latter review particularly interesting: Curtin sees two drawbacks to the game: the first one is the length of the game, the second one is the length of a turn “waiting” when playing against another human. Curtin has a solution though: “There is no reason why a player couldn’t make his move, save the game and transfer the file through a modem to a player elsewhere. Your opponent could then restart the game with this file, make his move, save the game and ship it back to you over the phone. I haven’t tried this yet, but it’s something I’m looking into.” That’s forward-looking indeed!

Computer Gaming World did not review War in Russia immediately, instead it published in August 1984 an article by Jon Cheche titled “War in Russia: the view of a playtester” with mostly advice in it, some trite and some valuable. I am amused that his advice for the Zitadelle [Kursk] scenario is that you are going to lose anyway (“it is more a study in futility“). In January and April 1985, Computer Gaming World published a replay of a multiplayer 1942 campaign between Kirk Robinson and Jay Selover. They only played 12 turns, and the front did not move much, possibly because Jay Selover focused on Moscow against an opponent who knew what he was doing.

The first “real” review came from the wargame expert Evan Brooks in his 1987 coverage of all WWII wargames (“5/5 – despite problems with the artificial intelligence in the later stages of the war, […] this is an essential addition to the serious wargamer’s library“) – this review triggered an angry letter to the editor in October accusing Brooks of double standards and pointing out that there are problems with the artificial intelligence from the onset of the game: apparently if you let the AI keep Minsk in 1941 it does not trigger its routine to defend Moscow and you can snatch it from the South.

War in Russia was also a favourite of the Computer Gaming World leadership. In March 1988, the magazine introduced the Computer Gaming World World of Fame for games which consistently ranked among the first in the Readership Surveys – War in Russia was part of that initial list.

In France, the (tabletop) wargame specialist Casus Belli praised it to the sky in November 1984 “The absolute wargame, the victory by KO of the diskette on the cardboard”, the review describes a unique experience that could never replicated on board, and describes the AI as very good. Disappointedly, its generalist competitor Jeux & Stratégie only gave War in Russia a 3/5 rating a few months later in February 1985. Finally, Tilt gave it a 5/6 rating in its December 1986 article on all contemporary wargames; no game received 6/6.

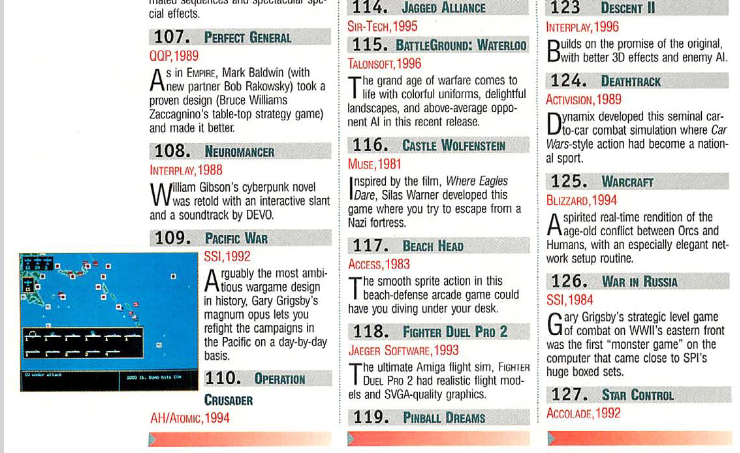

The last appearance of War in Russia was in the Computer Gaming World‘s list of 150 Best Games of All Time in 1996. It is ranked “only” 126th, but I let you check below between which illustrious games it is slotted:

Despite its critical acclaim, War in Russia did not sell that much: fewer 7 000 copies in the US (4500 Apple II, 2500 Atari) – significantly less than Carrier Force (15 500) and of course than an RPG like Questron (34 000).

We’re done with War in Russia, the first game in a long line that would lead to Gary Grigsby’s War in The East. Now I must delve into its engine again – this time for Objective Kursk!